"Bookshops are cool again"—A history of ever-cool Five Leaves Bookshop

Five Leaves Bookshop in Nottingham opened in 2013; since then the independent radical bookshop has gone from strength to strength. Staff are apid a living wage, the bookshop stocks a wide range of excellent titles, and there's also the Five Leaves publishing imprint! Books Combined spoke to Ross Bradshaw, owner of the store and editorial director of Five Leaves Press.

(Five Leaves Bookshop)

From 1979-1995 I worked in Mushroom Bookshop, a radical Nottingham bookshop (which closed in 2000). At the time it was considered very radical. It was a workers’ co-operative and was the base for organising anti-fascist and anti-war activities. Its politics, generally, were libertarian. Having said that, for a period it paid the best wages of any bookshop in town, was the first local bookshop to go computerised and had a library supply side which serviced schools and local university libraries. People in Nottingham now remember it as having a much more radical profile and stock than Five Leaves Bookshop, which opened in November 2013. But memories are often false – Mushroom had a humour section, sold a lot of Bill Brysonand majored in self-help! It might have been the mileau in which it operated that was more radical – there were at one time over 100 left-wing bookshops in the UK and Mushroom flourished in the glory days of political activism.

I left Mushroom and began publishing under the Five Leaves imprint. Our list was Jewish, radical, literary and strong on social history and young adult fiction. For many years Five Leaves did well but the culmination of the 2008 crash, the closure of Borders, Books Etc, the take-over of Ottakers by Waterstones and conservative buying from the remaining bookshops was making us think again.

(Nottingham City Centre, Flickr/DncnH)

I’d always regretted leaving the retail side of the booktrade and began to explore returning to bookselling. The signs were not good. The left was still weak, city centre rents high and the number of independent bookshops had fallen to below 1000 for the first time ever. But below the headlines I knew that the few existing radical bookshops, including Housmans in London, were attracting more interest as people began to think there might be different possibilities to the way our economy is currently run. I’d seen the growth of the very successful London Review Bookshop. Locally, I’d worked with The Bookcase in Lowdham, a village of 1,500 people which operated the year round as a village bookshop but developed a huge book festival – now in its 16th year – and seen how other small independents could put themselves at the heart of cultural activity in their area.

I spoke to a few friends about the notion of opening an independent and radical bookshop in Nottingham city centre. Some friends were overenthusiastic, others deeply pessimistic – neither view helped. It was time to call on my mother… who better to ask for advice than an 86-year old with dementia who had never worked in bookselling? She gave me the best advice yet. She said it would be three years before I really knew whether it would work so I should draw up a “bad budget” for the first three years, assuming failure. If I could afford the set up capital and three years of losses without risking ending up homeless of course I should do it. She came from a Scottish Traveller family, had been forced to leave school at fourteen and books had always been central to her life as they had been to mine so the prospect of a bookshop excited her. Agreed… but where to get the set up capital? (Every word here is true, by the way…) I looked around at the walls of her tiny flat in the Scottish Borders, reminded her that as well as having dementia she had a fatal illness and was not long for the world… “Great,” she said, “there’s your capital. How much do you think we’ll get for the flat?” “We won’t get anything,” I said, “but I might get… just enough to open a radical bookshop.” My mother was pleased. We celebrated with a cup of tea.

It was important to open near to the huge Nottingham Waterstones but, given, city centre rents, essential to find somewhere in a quiet street or one of Nottingham’s many alleyways, to keep the rent down. By chance I met a landlord whose tenants were going out of business. He offered a 500sq ft oblong in a central cul-de-sac alleyway next to a bookies. Low rent, just (then) the right size. I signed the lease on October 23 2013 and we opened on November 9th – one of a handful of independent bookshops to open in any city centre this century and one of the scarce few full-service radical bookshops in the whole country. (Five Leaves Bookshop)

(Five Leaves Bookshop)

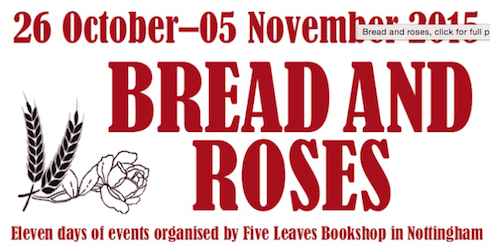

Two years later our stock has doubled – the shop is stuffed full. Our staff has increased, including one half time worker devoted to events. We have at least one reading or lecture in the shop every week and a dedicated radical book festival, Bread and Roses. In the first year guests included Owen Jones and the leader of the Green Party, Natalie Bennett. This year the festival is eleven days long and the keynote speaker is Shami Chakrabarti.

(Bread and Roses)

Like any independent bookshop we prioritise customer service – customer orders from the UK are here in 24-48 hours, from the USA in a week or two. The strongest areas in the shop are landscape and cityscape, radical politics and contemporary poetry. As well as events we do a lot of external bookstalls. It has been a struggle to keep up the publishing side, but we still managed to bring out significant titles including the book on Nottinghamshire in the miners’ strike (we also organised the Nottingham commemoration of thirty years since the strike) and a book on the forgotten architectural writer Ian Nairn which led to a renewed interest in his work. We also publish “occasional papers” from the Bookshop, some of which are based on author talks in the bookshop.

(Five Leaves Bookshop)

We work with all sorts of people, including a group initiating a Nottingham Poetry Festival. The list is too long to give here, but that includes Nottingham Waterstones, which hosted a launch by seven local short story writers published by the Bookshop (rather than our publishing wing). We like the way that all the local parts of the industry work together.

What makes a radical bookshop though? It’s not completely radical – the landlord needs rent paid! – but the mix of books, those we stock and those we don’t make it clear our heart is on the left. We are not prescriptive – Marxist, anarchist, left Labour and Green books happily rub shoulders. After two years we are already turning a profit (my mother was unduly pessimistic) and we pay our taxes – £1.20 for 2014 but we were in the black! Staff are paid the Living Wage. Our customer base continues to grow. We’d love to stock a bigger range of titles, for example more specialist scholarly books from university presses, but Nottingham is not a wealthy city and often the retail prices are high for us. What these presses do, however, is to fill the spaces left behind by commercial presses who find they make money from £60/£85 books that are only bought by university libraries. And American university press books often have the best covers.

(The Return)

My own reading is a bit all over the place. On a recent train journey back from Italy I read the first Elena Ferrante novel, being too embarrassed to read it in the country in which it was set. While there I read two London books, Rebel Footprints: a guide to uncovering London’s radical history by David Rosenberg (one of many Five Leaves’ writers who, I am pleased to say, have moved on to bigger publishers) and Ed Glinert‘s West End Chronicles. I confess to having also just read my first chicklit book but the excuse is that Deborah Meyler’s novel is called The Bookstore and has the subtitle “Love does not always go by the book”. Does that give me a pass? I’ve just started Ghada Karmi’s book The Return about her bitter-sweet experience returning to Palestine and a proof of Patti Smith’s set of memoir stories M Train. Working long hours in the bookshop – and still publishing – limits my reading, so the pile never gets smaller…

I am reasonably confident about the future. The bookshop had the advantage of opening after the rise of ebooks and Amazon. Neither bother us. People are turning away from Amazon because of its tax and employment practices while, in response to ebooks, books have become more attractive, more adventurous in their design. Bookshops – we like to think – are cool again…

(Five Leaves Bookshop, Ross Bradshaw)

Ross Bradshaw, owner of Five Leaves Bookshop and editorial director of Five Leaves Press, was interviewed by BooksCombined where this article originally appeared.