A Third World Olympics: Sport, Politics, and the Developing World in the 1963 Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO)

Although GANEFO’s genesis was related to diplomatic problems that arose from Indonesia’s hosting of the IVth Asian Games in 1962 and the subsequent suspension of the Indonesian Olympic Committee, it was also an explicit attempt to link sport to the politics of anti-imperialism, anti-colonialism, and the emergence of the Third World.

Jules Boykoff, in Power Games: A Political History of the Olympics, surveys the Olympic Games of the Cold War era following the Soviet Union's return to the IOC at the 1952 Helsinki Games. As the meaning and structure of Olympic competition became increasingly distorted around First–Second World antagonism, an alternative emerged with the 1963 Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO), held in Indonesia and launched by President Sukarno.

"But, like the alternative Games that preceded it," Boykoff concludes,

this “new sports grouping” didn’t last long. Organizers planned GANEFO II to take place in Cairo in 1967, but the financial burden of staging the competition, along with Sukarno’s overthrow by Suharto in 1966, sapped the energy from the movement. GANEFO II was never to be. But the Games of the New Emerging Forces demonstrated that the Olympics — and sport more generally — are eminently political. Alternative models for organizing sport along political lines were indeed possible.

Historian and sports scholar Russell Field is working on a book-length history of GANEFO and recently contributed an article on the 1963 games to Sport, Protest and Globalisation: Stopping Play, edited by Jon Dart and Stephen Wagg. In the original piece below, Field considers GANEFO as a lens through which to understand sport and politics in the era of the Cold War and the Non-Aligned Movement and as a reference point for contemporary debates.

“We’re observing a dangerous relapse into the interference of politics in sport… to make sport an instrument of geopolitical pressure and the formation of a negative image of countries and peoples. The Olympic movement, which plays a colossal unifying role for humanity, could again wind up on the edge of schism.”

“This politically inspired, politically organized, and politically directed enterprise is the antithesis of sport and should be avoided by all sportsmen … [It] might split the world of international sport asunder.”

As a scandal-plagued and controversial Summer Games get under way in Rio, the rhetoric has become equally Olympian — as the quotations above would suggest. Yet, despite their similarities, these words were spoken (or written) more than half a century apart. The first is the bluster of the Russian leader, Vladimir Putin, trying to spin a defense for the drug controversy within which his country’s sport leaders find themselves embroiled.

The second quotation, however, comes from the former president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), Avery Brundage, and in 1963, he wasn’t trying to deal with a drugs scandal. He was trying to buttress the Olympic movement as a First World institution in a rapidly decolonizing world; making his apparent angst all the more relevant as the Olympics head south of the equator for the first time (excepting Australia in 1956 and 2000).

The enterprise to which Brundage refers was the now little-remembered Games of the New Emerging Forces (or GANEFO). Although GANEFO’s genesis was related to diplomatic problems that arose from Indonesia’s hosting of the IVth Asian Games in 1962 and the subsequent suspension of the Indonesian Olympic Committee, it was also an explicit attempt to link sport to the politics of anti-imperialism, anti-colonialism, and the emergence of the Third World. GANEFO was founded by the Indonesian president, Sukarno, whose ambitions were grand enough to imagine both a quadrennial competition (GANEFO II was scheduled for Cairo in 1967) and a larger unrealized political movement. But except for an Asian GANEFO hosted by Cambodia in 1966, the Games themselves were never held again.

Beyond its Asian origins, GANEFO resonated around the world and is a lens through which to examine sport and politics during the Cold War. The event was, as Brundage suggests, widely opposed by mainstream (and First World) sporting institutions, who rejected what they saw as the comingling of sport and politics. Indeed, in threatening suspensions to athletes who competed in Jakarta, the IOC insisted that the international sport federations take the responsibility of policing GANEFO participation — which is one, among many, precedents for how the IOC has handled the Russian doping scandal in 2016.

A Third World Olympics?

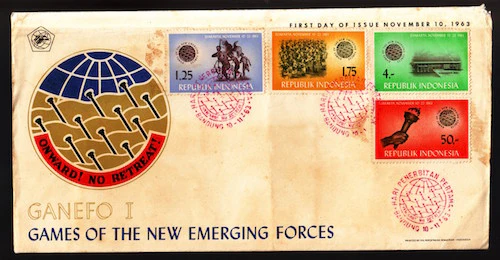

Branded with the slogan “onward, no retreat,” GANEFO took place in Jakarta, in November, 1963, and attracted approximately 3000 athletes and officials from — but not necessarily officially representing — nearly 50 nations. They met in the Indonesian capital and competed in 20 athletic events (virtually all of them Olympic and Western sports) as well as cultural festivities. Athletes hailed primarily from recently decolonized countries in Asia and Africa (as well as former colonies in Latin America), which were labelled the “new emerging forces” by Indonesian President Sukarno. After the hosts, however, the largest teams represented the Second World, the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union.

The event took shape at a preparatory conference held in Jakarta in April 1963. There, the hosts were joined by representatives from Cambodia, China, Guinea, Iraq, Mali, Pakistan, North Vietnam, the United Arab Republic, and the USSR, with Ceylon and Yugoslavia attending as observers. This meeting formulated a plan for GANEFO and a subsequent conference intended to solidify the political unity of the new emerging forces, and concluded by noting that the “countries invited to take part in the First GANEFO in Jakarta are those accepting the Spirit of the Asian-African Conference in Bandung and the Olympic Ideals.”

Such an invocation of “Olympic ideals” is intriguing given Sukarno’s critical stance towards the IOC and the colonial role played by the Olympic Games. Nevertheless, as athletes gathered for the Opening Ceremonies on November 10th, they were greeted by a crowd of approximately 100,000, who inaugurated an international multi-sport event that very much resembled the Olympics, complete with such symbols and rituals as opening and closing ceremonies, a torch relay, flame lighting, symbolic flag raising, and a parade of athletes into the stadium, who stayed in a residential “village” and competed in adjudicated sporting events, and were awarded gold, silver, and bronze medals.

Why Indonesia?

While Brundage, wanted sport to be “independent” of political influence, Indonesian Foreign Minister, Subandrio, contended that “sport cannot be separated from politics, and Indonesia uses sports as a political tool to foster solidarity and understanding between nations.” For Sukarno, GANEFO was “a matter of national prestige” and an event that would elevate Indonesia to “the front ranks together with the other countries standing in front of the struggle for a formation of a new world structure.”

In the West it is all too easy to overlook that Indonesia is the largest Muslim country in the world and that, in the early 1960s, its geopolitical significance and resource wealth gave it significant influence in the nonaligned world and made it a focus of Cold War maneuverings. As a result, there was a significant development subtext to GANEFO: international athletes and guests arrived in Jakarta and travelled along a highway paid for by United States aid, stayed in the International Hotel constructed by Japanese investment, and competed or spectated at the massive Bung Karno sports complex originally built by the Soviet Union for the 1962 Asian Games, all for an event financed by China.

Not All Quiet on the Western Front

GANEFO was portrayed in the Western media as a “red” event because of Sukarno’s ties to the Indonesian communist party (PKI) and the Games’ sponsorship by China. In September 1963, two months in advance of the event, a US State Department communiqué, over the signature of Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, was sent to US embassies around the world instructing diplomatic officials that “On balance, the disadvantages of GANEFO to the Free World far outweigh any discernible advantages.”

Officials from international sporting bodies were even more concerned over GANEFO’s explicit mixing of politics and sport. According to Brundage, “the Indonesia Government has thrown down a challenge to all international amateur sport organizations, which cannot very well be ignored.” An immediate concern was that GANEFO was occurring only 10 months before the first IOC Games in Asia. The response was to threaten competitors with a ban from the Tokyo Games if they competed in Jakarta.

The IOC argued that determining eligibility and meting out punishment for participating in GANEFO should be the responsibility of the international sport federations (IFs) — which is exactly how the IOC handled the Russian doping scandal in the past month. Nevertheless, the documentary record makes clear that IOC officials took a very hands-on approach, warning their constituent national Olympic committees of the potential for sanctions in advance of GANEFO and then attempting to gather information on who did participate in Jakarta — details that were passed on to the IFs.

Tensions in the Second World

Athletes from the African nations who attended GANEFO had their travel costs paid for by the Chinese state. China saw an opportunity in GANEFO, first to re-enter international sport in a highly successful fashion. China had withdrawn from the IOC over the recognition of Taiwan, and the 229-person Chinese team (second largest at GANEFO) won the medals table. Secondly, China sought to curry favour within Indonesia and the Afro-Asian world. This highlighted Second World tensions between China and the USSR, as the event was implicated in Sino-Soviet struggles for influence in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

The USSR faced trickier diplomatic options. Its return to the Olympic Movement in 1951 and the role played by Konstantin Andrianov as an IOC executive member highlight the importance of sport to Soviet foreign policy and propaganda. While China offered to subsidize all African participants in GANEFO and sent its best athletes to Jakarta, the Soviet Union tried to balance supporting GANEFO (it sent a full team, but not its best athletes) while protecting the influence it held within the IOC.

Since When Are Europeans Part of the New Emerging Nations?

While Indonesian and Chinese officials hoped that GANEFO would inaugurate a quadrennial rival to the IOC Games, as the event approached there were concerns that the threatened sanctions would negatively impact participation. Despite the rhetoric of the emerging forces, fears that the numbers of athletes would be smaller than hoped for compelled the organizers to consider a variety of entrants, or what the US Embassy in Jakarta, characterized as “Indonesian willingness to accept any type of sports delegation, whether sent by a national sports association or merely by a ‘progressive’ group in the country of origin.” These included leftist sport clubs from Cuba and Uruguay along with less radical student sporting associations from Argentina and elsewhere in South America, who thought they were attending a university competition.

Somewhat surprisingly, on the surface at least, given the event’s framing around the emerging forces, there was Western European participation at GANEFO. Athletes from Finland, France, Italy, and the Netherlands competed in a variety of events. These athletes represented leftist student unions and sport clubs — a legacy of the European worker’s sport movement. Given the Netherlands’ colonial history in the region, the presence of the Dutch contingent, four swimmers and three yachters, is particularly interesting.

The swimmers represented the Nederlandse Culturele Sportbond (NCS), the Dutch worker’s sport club. Guus Ruijgrok of Zaandam, recalled that he expected to attend a swim meet when he arrived in Jakarta and was amazed by the scale of what he encountered. Moreover “for us it was a surprise that we should take part in the Games of the New Emerging Forces, we thought that the Netherlands was something completely else.” This makes the case of his teammate and fellow Zaandam resident, 16-year-old Guda Heyke, telling. She won the gold medal in the 100m freestyle and received a warm reception from the Indonesian crowd, as did the Dutch team at the Opening Ceremonies — a fascinating post-colonial reaction that merited mention in 1963 in both the Dutch and Indonesian press.

Conclusion

Among historians, especially those interested in the interplay of sport and politics, the 1960s are a prominent decade offering examples of athlete activism and civil rights, protest and resistance around sport, and the debates within the sport community about how to respond to apartheid. GANEFO offers an opportunity to refocus the examination of sport and politics from the perspective of what today would be labelled the Global South in an era of decolonization. In an event too easily dismissed as either an Indonesian folly or read through a binary Cold War frame, GANEFO offers an opportunity to view through sport the complex interplay of agendas and priorities within and between all Three Worlds and the intersections of nationalist projects, geopolitical forces, and lived human experience.

Russell Field is a historian interested in the socio-cultural study of sport and physical activity, at University of Manitoba. He is editor of Playing for Change: The Continuing Struggle for Sport and Recreation and co-editor (with Bruce Kidd) of Forty Years of Sport and Social Change: 1968-2008. He is the founder and executive director of the Canadian Sport Film Festival.

Jules Boykoff's Power Games: A Political History of the Olympics is out now.