Corrupting the Youth: A Conversation with Alain Badiou

At 79 years of age the philosopher Alain Badiou surveys the youth: the youth whom liberalism has left without a compass, the youth tempted by Daesh, and so, too, his own youth, marked by communism, to which he remains faithful. Interview by Juliette Cerf for Télérama. Translation by David Broder

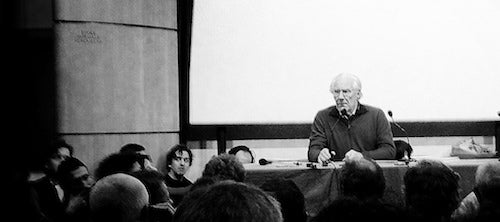

Photo by Jean-François Gornet. Via Flickr.

In Alain Badiou’s essay published in the wake of the 13 November Paris killings, "Notre mal vient de plus loin," he puts things directly: "Our ills today come from the historic failure of communism." Faithful at whatever cost to the Maoist ideals of his youth, applauded by some and jeered by others, this politically-committed philosopher is the author of a multi-faceted oeuvre that has been translated worldwide. It ranges from metaphysical tomes based on mathematics like Being and Event and Logics of Worlds — soon to be followed by a third volume, L’Immanence des vérités — to a series of political interventions named Circonstances, via plays for the stage, seminars on the great thinkers of the philosophical tradition, books for the wider public like In Praise of Love, and his translation of Plato’s Republic. This abundant output is reflected in three of his essays published this summer: La Vraie Vie. Appel à la corruption de la jeunesse (Fayard), Un parcours grec. Circonstances 8 (Lignes) and Que pense le poème? (Éditions Nous). Here we meet a fierce critic of capitalism, faithfully radical as he is radically faithful.

Why did you want to address youth in this new book, La Vraie Vie?

A number of different factors came together. Firstly, personal factors put me face-to-face with the great disorientation that the youth is today experiencing. Since the 1980s it has gradually seen the horizon of the possible closing down. I have seen the difficulties my children and their friends have had in traversing the world such as it is, and finding their place within it. I’ve seen young people’s growing tendency toward self-depreciation. Moreover, I have been surrounded by students, and having long been politically active in migrant hostels and factories where I was frequently in contact with a nomadic working-class youth bearing a rich experience drawn from extraordinarily diverse situations. And then there’s the fact that one of my great sources, Plato’s dialogues, is made up of discussions between Socrates and young people. For the tradition I set myself in, youth is simultaneously both the very question of philosophy and its destination. The philosopher tries to transmit something that might still be of value in the future, and in this sense, his audience is always the youth… To philosophise is to research the question of truth in the conditions of one’s own time. But the youth also enters into a world that is in becoming; it is also seeking its bearings and points of fixture. That is its very process. Youth’s problem is exactly the same as the philosopher’s, though it doesn’t know it!

Like Plato you call for the "corruption" of youth. But how does wanting to help young people to orient themselves, to find truth, constitute a form of corruption?

What were Socrates’s judges reproaching him with when they accused him of corrupting the youth, and condemned him to death for doing so? They reproached him with putting in doubt certain aspects of tradition, of openly flaunting his impiety with regard to the gods of the city, of turning the youth away from its familial and civic duty. If philosophy "corrupts," that is because its function is more critical than conservative. However, in this regard the current situation is more complex than the situation in Plato’s time. Today the great landmarks of tradition have been destroyed, but without society proposing new ones in their place. There are new pleasures [jouissances], yes, but not new values. Everything has dissolved in the fascination for the commodity, in what Marx called the "icy waters of egotistical calculation." Young people are wedged between, on the one hand, the mortifying possibility of a return to tradition — which is always a matter of resuscitating a corpse and bringing ghosts to life — and, on the other hand, the possibility of taking a place in the general competition and struggling for their own survival therein, to the sole end of not being a loser. What I, following Rimbaud, call the "true life" is a third way: neither the return to defunct traditions nor the adoption of the rules of globalised capitalism, which whatever their semblance of civilisation are in reality brutal and savage. At an extremely young age Rimbaud was acutely conscious of the disorientation that was on its way. He saw very clearly that the old Christ had abandoned the Earth. He roamed through the world, where he did a little of everything, including poetry, one of his ‘follies’. He burned through life before concluding that the modern world is money and success. He then became a colonial trafficker…

So what is the true life?

A life that does not limit itself either to obedience or the satisfaction of immediate impulses. A life in which the subject constitutes herself as a subject. For me there are four domains in which truth manifests itself, what I call the four procedures for the construction of truth: art, love, politics and science. My wish for the youth is that they traverse these four conditions: to encounter art in all its forms; to be loving in fidelity, and for a long time; and to participate in the political reconstruction of a world of justice, as against the world such as it is. And not to be as ignorant of science as they currently are, so that they do not leave it in the hands of technology or capital.

You devote one section of your text to young men and women: is the difference between the sexes still relevant for thinking about youth today?

Yes. The weakening of traditions has not had the same effects on young women and on young men. It has opened up more doors to women, who have little-by-little been liberated from the male oppression and dependence on marriage that reigned in the old world. It has opened up career prospects and possibilities that they did not previously have. Ultimately young women are more at ease in the contemporary world than young men, and that includes doing better at school. I have attended trials of young men who are completely disoriented: petty dealers, mock local bosses in the cités [projects/council estates]etc. Their sisters, for their part, were lawyers… For young men the disappearance of military service symbolised the general disappearance of any initiation. For thousands of years the question of youth and reaching adulthood was governed by regulated procedures that set out the relevant thresholds. Nowadays identifying the different ages of one’s life is difficult, hence the cult of youth — the fact that the norm is now to remain young as long as possible, even when power remains in the hands of the old and there also reigns a fear of young people, gangs of young people… All this creates a general confusion.

In some of your recent political interventions another youth appears: the young people enrolled by Daesh, who you characterise as "young fascists."

The word "radicalised" is very much in fashion, but I prefer the term "fascists." I use "fascism" as the name for a popular subjectivity generated by capitalism which mixes into an identitarian, nationalist discourse. Fascism is a reactive subjectivity: indeed, these young people have often experienced the frustration that goes with being nothing more than a petty trafficker in the cités, and the disillusionment over not having been able to become a great hero of capitalism. They reject the rather desolate and opportunist roam through immediate, worldly satisfactions, as well as the harsh law of competition and success. They situate themselves outside the alternative most youth live through — the alternative between consuming and burning up one’s life in transgression and immediacy, or taking a place in society, becoming a banker or the manager of a start-up listed on the Stock Exchange. Their nihilism is a mix of sacrificial and criminal heroism, and a general aggression toward the Western world. This fascist aggression is based on forms of traditional and identitarian regression, on the debris of tradition that are offered to them, in part by Islam. It is the fascisation that Islamises them, not Islam that makes them fascist. Religion is but a formalism; it proposes a general envelopment allowing the satisfaction of a frustrated subjectivity that thinks it can save itself through suicidal acting out and the murder of the other.

What kind of young person were you? What animated you at that time?

I was born in 1937. My youth took place in a completely different world – the postwar world of the reconstruction of France, a period that was simultaneously both structured and dynamic. Class differences were very marked at that time. Young people from working-class or peasant backgrounds ended their studies at 12 years of age, and only 10 percent of each age group passed their baccalaureate. The Communist Party was very strong and enjoyed a powerful aura, through its association with the victorious Soviet Union. Two different orientations were taking shape: the capitalist reconstruction of the country, or the proletarian orientation embodied by the Communist Party. Revolution or conformism? Or having it both ways?

Did you have it both ways?

Yes. I did not come from the masses, by birth I belong to the upper half of the middle class. My parents both went to Écoles normales [élite higher education] and my father was Socialist mayor of Toulouse. I embody the typical intellectual figure (having been through the École normale and then agrégation [competitive exam to become a professor]), at the same time as choosing to be intellectually on the side of the revolution. In the end this was a rather comfortable arrangement, since you could thus have the advantages of both ways, following in the tradition of what the audience of the eighteenth-century philosophes did. It was the colonial wars that disturbed this double-game. My true political education was the Algerian War. It was that which made me take radical decisions. Even though that was in an era when people were being tortured in the Paris police stations… That was a moment when you had to commit yourself against the current, break out of your comforts and set your life in tune with your thinking. The first demonstrations we organised were very violently repressed – posters everywhere denounced "defeatist intellectuals." I participated in the split in the Socialist Party, which gave rise to the PSU. After May ‘68 I became a militant very active in the workers’ hostels, in the cités, in the factories. I did so under a Maoist label, which — together with the Trotskyist label — was one of the main determinations of that era.

Of that era, you say. But you still are a Maoist, and your detractors attack you for that

Indeed, I do hold on to the communist hypothesis. I refuse to inhabit a world in which the currently hegemonic social and economic organisation is the only hypothesis. I cannot accept this monstrosity, this inequality, the fact that 10% of the planet’s population possesses 86% of the available resources, of capital. Far from being obsolete or ready to be chucked away, the communist idea is, in my view, still too young. It is at the very beginning — lasting a few decades — of its historical journey, while capitalism, born six or seven centuries ago, is reproducing the throwbacks, the inequalities of the ancien régime — indeed, 10% is more or less the percentage of the population that were nobles in that era… I should make clear that I know perfectly well the vices and the crimes of the communist societies. I became a Maoist because I identified in Maoism certain critical elements for surpassing and changing Stalinism. The period that opened up with the Russian Revolution of October 1917 was punctuated with errors and dramatic falsifications, the main one being that although in its very principle communism bore a distrust for the centralised state, it ultimately built a state more centralised and bureaucratic than any that had gone before, a state that gave in to the temptation to regulate every problem through violence. The communist hypothesis ran aground in its earliest successes and the lean sixty years that followed. So should that lead us to abandon the hypothesis itself? I don’t think so. We should not heap a total ideological defeat onto a circumstantial defeat.

What is your understanding of the coming election year and the return of Nicolas Sarkozy — to whom you devoted your fierce 2007 pamphlet, The Meaning of Sarkozy?

I haven’t voted since June 1968, and at my age I don’t think I’ll be giving in… It would be pointless. Electoral consultation is just a consultation internal to the established order, the mediation of a few nuances within one same way of managing things. The Left continues exactly the same policy as the Right. And we cannot speak of democracy when there is not a real choice between two different paths. You mention Sarkozy. Well, there we’re talking about an allergy of mine! It must be that I still have a certain residual patriotism, inherited from my father who was in the Resistance, but I can’t stand a head of state being such a scumbag… But in fact Hollande’s policy has not been substantially different from Sarkozy’s. Hollande has even accelerated the dismantling of past social conquests. He has theorists at his side like [finance minister Emmanuel] Macron to justify that, in the name of modernity. For him modernity means returning to the nineteenth century, to liberalism, the natural ideology of capitalism, which has no love for social regulations, the right to work or pensions. This ideology today enjoys full freedom of action it has no strong enemies to deal with. I propose that we hold onto the hypothesis of its only real enemy: communism. And that we continue to philosophise, because while we know perfectly well who Plato was, in two millennia from now — and that’s the temporal scale of philosophy — absolutely no one will know who Sarkozy was.