(No) Future, (No More) Heroes: Benjamin Noys on Berardi's Heroes and Futures

Ahead of his ICA: Culture Now event in conversation with Franco 'Bifo' Berardi, Benjamin Noys ventures in search of 'the place to begin not so much thinking the ‘future’ as thinking the present', via Heroes.

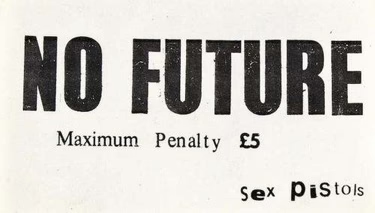

The Sex Pistols’ ‘God save the Queen’, with its closing refrain ‘No Future’, The Stranglers’ ‘No More Heroes’, and David Bowie’s ‘Heroes’, are all released in 1977. On the one hand, this is the end of the future and the end of heroes, the apocalyptic moment when the ‘two sevens clash’; on the other, this is the beginning of another future and other heroes, seen in the fragile optimism of Bowie’s ‘we could be heroes / just for one day’ or, more disturbingly, in the signs of the emergent neo-liberal counter-revolution. The apocalypse, however, would be disappointing.

The punk moment of 1977 trapped itself in the dialectic of recuperation: outside/inside, autonomy/heteronomy, independent/major label. ‘You think it’s funny,’ The Clash sung, ‘turning rebellion into money?’ Advice they might have taken better to heart, as they had signed to CBS and The Sex Pistols to Virgin. The hard work had yet to begin.

1978 was the year of Subway Sect’s split single ‘Ambition’/’A Different Story’. The chorus of ‘A Different Story’ was ‘We Oppose All Rock and Roll’:

The lines that hit me again and again

Afraid to take the stroll

Off the course of twenty years

And out of rock and roll

Subway sect refused any ‘rock posturing’. Post-punk was the time of the struggle for autonomy, for independence, as something not pre-given in some ‘pure’ state prior to the ‘inevitable’ recuperation, but fought for in the face of producing, distributing, and playing music. In 1981, obviously playing on the S/M connotation, Throbbing Gristle declared ‘we need a little discipline’. This moment too would fail, but be less remembered.

Subway Sect

1977 was the end of the moment of Autonomia, the mass-movement of revolt in Italy that exploded before crashing in the face of state repression. Unable to overcome this limit Autonomy disappeared in exile, in prison, in the face of armed violence by the state and radical groups, and finally in the new compromises and concessions that would make-up the new capitalist restoration. For Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi the convention on anti-repression called in Bologna in 1977, attended by 20,000 people, is the sign of this imminent failure – a capitulation to the ‘anti’, a failure to construct autonomy, of becoming lost in the dialectic. This is another version of the dialectic of recuperation, of dissipating energy, of heroic failure.

Post-autonomist thinking, the attempt to continue after this failure, does not make the same inquiry into the problem of autonomy as did post-punk. Autonomy continues to be a matter of faith, especially in the work of Toni Negri, which tends to find autonomy everywhere, even in the unlikeliest of places. Autonomy remains as the insurgent force of the multitude and every defeat is, if looked at closely enough, a victory in disguise. It is one of Bifo’s virtues to have questioned this optimism, although he has not gone far enough. Bifo has always been attuned to the pathological effects of the failures of autonomy, the psychic costs of capitalist (damaged) life, to a certain negativity, if not to any alternative negativity, any negativity that is not simply synonymous with suffering.

Bifo’s Heroes is a book of these pathologies, often drawing-on and recapitulating his past discussions. There is repetition here. A litany of mass murders and suicides, of school and workplace shootings, of suicide bombers, of various forms of desperation and what Banu Bargu calls ‘weaponized life’. When there is nothing left to lose, it is better to risk death than live a life of nothing. Ozzy Osbourne’s ‘Suicide Solution’ (1980). At the start of his conclusion to Heroes, Bifo asks ‘Why did I write such a horrible book?’ Bifo is right that people hardly need to be told how bad things are. Robert Kurz had noted, in 2002, that: ‘The psycho killers are robots of capitalist competition gone haywire: subjects of the crisis, dedicated to the concept of the modern subject, and fully educated in all of its characteristics.’ Much more difficult, much more obscure, is his suggestion we need to find a line of flight. In the face of what Bifo calls, resonantly, ‘capitalist absolutism’, how should we image ‘flight’? Is ‘flight’ even the right figure for the possibility of resistance?

Image from Michael Haneke’s 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994)

There is the bad (male) depression of modernity, Lenin’s depression, which for Bifo leads to a manic voluntarism to break out of this depressed state. This is a kind of ‘manic-depression’, a wild oscillation. There is also the depression of our late modernity, the depression of exhaustion, over being overwhelmed by the cognitive demands of capitalism, and in response the wild ‘acting-out’ of the ‘robotic killers’. But, for Bifo, there is also a potency of depression, a flight through depression and the worst. Don’t build a shelter, Bifo advises, but engage in ‘ironic autonomy’, find independence in the face of absolute dependency.

The last photograph of Lenin (1924)

It is not difficult to return Bifo’s accusation against Lenin to sender. If Lenin tried to ‘construct’ a proletarian party in the face of a decimated working class and in a peasant country, facts of which Lenin was well aware, then is the construction of a ‘party of autonomy’ also anything other than an act of will, of another type of voluntarism? A line of flight to ‘ironic autonomy’ can only appear as a wilful denial of our dependency on ‘capitalist absolutism’. The result is that the swings in Bifo’s own texts between despair and elation seem much more marked than those in Lenin’s.

There is one passage in Heroes I find striking. It tells of a car journey Bifo undertakes from the airport to Seoul. I’d like to quote the end of that passage: ‘The sea had receded and the ground was grey and brownish like the sky. Abstraction grey. Calmly, intensely, hopelessly, the ultimate abstraction took hold of me.’ It seems to me that the ‘abstraction grey’, which recalls Hegel’s ‘grey on grey’ of theory, is the place to begin not so much thinking the ‘future’ as thinking the present.

Benjamin Noys is Professor of Critical Theory at the University of Chichester. His more recent work is Malign Velocities: Accelerationism & Capitalism (Zero, 2014).