Good To Know You!

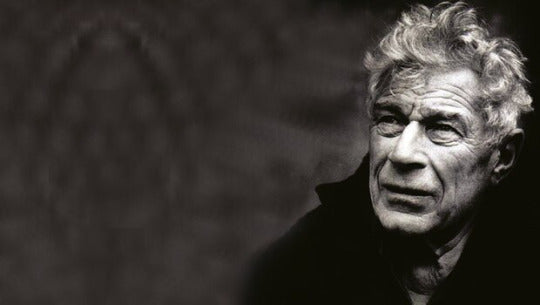

Andy Merrifield pays tribute to John Berger, who passed away aged 90 on 2 January 2017.

John died yesterday. I’ll remember his voice, his laugh, his charm and generosity. His words. Stripped-down words, mystical and carefully chosen words, earthy words, fierce words. They’ll always grab us, make us think, feel and act, piss people off. To weep for John is to weep on the shoulder of life. Remember him, gazing up at Aesop, in front of Velázquez’s great canvas?

He’s intimidating, he has a kind of arrogance. A pause for thought. No, he’s not arrogant. But he doesn’t suffer fools gladly. The presence of Aesop refers to nothing except what he has felt and seen. Refers to no possessions, to no institutions, to no authority or protection. If you weep on his shoulder, you’ll weep on the shoulder of his life. If you caress his body, it will recall the tenderness it knew in childhood.

John didn’t suffer fools gladly, either.

Poetic humanism was John's language, like Wordsworth. His was a finely-textured animal and mineral Marxism that journeyed over distances and across cultures, beyond disciplinary borders and through mental divisions of labour. John, who called himself a “jack of all trades,” said writing should be an act of joining things together, making sense of disparate things, and seeing that they’re not so disparate after all. He was driven to demystify productive and creative processes.

Death was forever part of John’s life. Storytellers, he said, are “Death Secretaries”; they borrow their authority from the dead. Death hands storytellers the file, “full of sheets of uniformly black paper.” “All the storyteller needs or has is the capacity to read what is written in black.” So now we, too, must read John in black. He’s handed us the file.

Decades of riding his Honda Blackbird 1100cc motorbike, along narrow mountain passes at breakneck speeds, must have taught John the thin line between living ecstasy and rapid death. A patch of black ice here, a mishap there, a careless motorist around the bend… it’s all over, you’re rolling down the valley of the damned. Or was it living amongst peasants that sensitised his awareness of death – the proximity of dying people, with moribund traditions, clinging grimly onto bare life? Death let John marvel at the wonders of the life-spirit, of daily life as epic drama and Greek tragedy. “It seems that I write mostly about the dead and death. If this is so, I can only add that it is done with a sense of urgency which belongs uniquely to life.”

“Everything’s a question of how you lean,” explains motorcyclist Jean Ferrero in To the Wedding. Ninon, Jean’s daughter, just diagnosed as HIV-positive, recounts this lesson as her father heads to her wedding in a village in Italy. A little parable on life that one: it’s all a matter of how you lean – how you deal with inertia, how you deal with the life’s gravity and grace.

John once took Spinoza for a spin on his Blackbird: “Coming for a ride, Bento?” “I wouldn’t make a direct comparison between a motorbike and a telescope for which you ground lenses,” he wrote in Bento’s Sketchbook, “yet they have certain features in common: both need to be well-aimed, both diminish distance, and both offer a tunnel of attention and the sensation of speed… In the tunnel of speed there is also a kind of silence, and when you get off the bike or remove your eye from the eyepiece, all the slow repetitive sounds of daily life return, and the silence recedes.”

He was still at work on Bento’s Sketchbook, the book I’ll most cherish in his oeuvre, when I was writing my book on his life and work several years ago. At the time he lent me a wonderful handmade maquette of the text in progress, his only copy. Thus Bento’s Sketchbook for me became a fascinating insight into Berger’s Sketchbook, into John’s annotated prose, his crossings-out, his finger-smudged drawings, his doubts. If he was trying to access Spinoza’s workshop, as well as the mind behind those propositions and demonstrations, now I could enter John’s own workshop, be privy to the private gleam of his unpolished diamonds.

You pilot a motorbike with your eyes, Bento’s Sketchbook says. All things for John always came back to ways of seeing, his eternal recurrence. Ways of riding are really ways of seeing, and ways of drawing. “For many years I’ve been fascinated by a certain parallel between the act of piloting a bike and the act of drawing. The parallel fascinates me because it may reveal a secret. About what? About displacement and vision. Looking brings closer.”

Think of a motorbike’s trajectory as something similar to a drawn line. “You are riding a drawing,” John said; you traverse an immanent plane, travel over contours, across smooth space, folding, unfolding, and refolding as you go. Drawings and motorbikes unite around intuitive reason and express common notions. This seems to be what John tried to transmit in Bento’s Sketchbook, as he did in all his books: common notions.

John’s whole life represents a species of eternity; his art lies beyond duration, beyond space. A lightness of touch, resembling the “geometrical” deftness of Spinoza’s Ethics, lies everywhere in his work: the culmination of all those years of restless activity, of writing and thinking, of drawing and riding, of meeting and discussing. The finally-achieved “blessedness” and mortality of Spinoza’s “third level of knowledge,” knowledge that John spent ninety-years searching for.

A religiosity, this third kind of knowledge, was present in his being and his work in recent years. Not a religiosity of institutions, of churches and commissars, of higher powers; not a God above us, a transcendent creator who offers us freedom only after death in heaven. John’s God is monadal and metaphysical, like Spinoza’s, a single substance with infinite attributes, inside us, in nature, inside both us and nature, an immanent essence we can tap without meditation or mediators, something we can experiment with, struggle for, sketch out.

And so, too, is the Godhead in the Blackbird, in the Blackbird we can hear starting up in our heads, revving up one last time in our memory, ready for its journey back home, to its final foyer in Mieussy. So long, we might say, like the Woody Guthrie song, it’s been Good To Know You! Fly Blackbird, fly… fly into the light of the dark black night…