"I see some of these kids and think, they are amazing." An excerpt from Chasing The Harvest

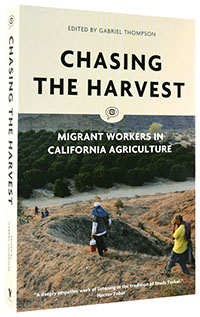

An excerpt from Chasing the Harvest: Migrant Workers in California Agriculture, edited by Gabriel Thompson.

Oscar Ramos is intimately familiar with the challenges facing kids in East Salinas. He’s taught at Sherwood for the past twenty years, and grew up in a labor camp on the outskirts of Hollister, a small city thirty miles northeast of Salinas. Ramos arrived in this country as an undocumented immigrant and worked in the fields until the eighth grade. Students are often amazed when they hear his story: a kid from the fields who graduated from college? “Yes,” Ramos tells them. “And you can do the same.”

An excerpt from Chasing the Harvest: Migrant Workers in California Agriculture, edited by Gabriel Thompson.

All books in the Voice of Witness oral history series are 40% off until Sunday, August 13 at 23:59 PST. Click here to access the discount.

I tell my story to my kids every year. I didn’t used to, but one year I thought I’d tell it just to see how they reacted. They went home and told their parents that I grew up in the labor camp and from the time I was eight I would work in the fields. During parent conferences it would come up. Parents would ask me, “Teacher, is that true? You know, my daughter told me that you used to do this.”

Because I lived through it. I experienced it. I didn’t learn about their experience through a book.

Like, “Oh I read that this is what it’s like to be a farmworker.” Everything is genuine. So I think that helped, telling them my story.

I’ve been at Sherwood for twenty years, and eighteen of them have been teaching third grade. This is why I like third grade: it’s the age where you can have a mature conversation. Eight years old, nine years old—you know, they get it, they understand. You tell a joke and they’ll get it and they’ll laugh.

It used to be that we would lose half our students in the fall and winter, because most of those students had parents that were traveling for farmwork. They’d start leaving for Arizona in November and wouldn’t be back ’til April.1

The class you started with wasn’t the class you ended up with. We had a fourth grade teacher who started one year with twenty-eight students. Only three of her original students ended that school year. That constant movement is the entire East of Salinas story.2

This particular student, Jose, he’s always moving. Every year he would go to a different school. Sometimes during that same school year he’d move twice, and I think in one school year he moved to three different schools. And when he got to my class, in third grade, he wasn’t going to finish the school year. He told me that he was going to move.

I’d read his file. I saw that he’d been to five different schools already. He’d never finished a grade in one of the schools, and I didn’t want that for him. I talked to the principal. I talked to his mom. His stepfather was working in Arizona. And they agreed. I’d pick himup in the morning and drive him to school, and his mom would pick him up after work. I did that for a few months so he could finally finish one grade in one school.

Jose would come in and fall asleep, but I wouldn’t wake him up. I knew why he was falling asleep, because that’s the same thing that used to happen to me. His mom would wake him up at three or four o’clock in the morning when she took him to the babysitter’s so she could go to work, and then he’d take a nap and they’d go to school. But once your night is broken up, it’s not the same—you’re gonna be tired the entire day.

We’d have snacks in the classroom, and he’d ask for two snacks. I knew why Jose was asking for two snacks—he wasn’t eating; there was no food at home. So yeah, there are all these challenges that come with kids that move around and those are just some of them. I’m sure there’s more that I’m not aware of.

Kids like that, they’re usually very shy; they’re very quiet. Because they figure, Why speak, why make friends, if I’m gonna end up leaving? And why try hard because when I move to another school they’re gonna be doing something different? And they feel defeated.

Or they act up. I get in trouble, so what? I won’t be here much longer. The principal suspends them and, It’s fine, I’m gonna be in another school. So it’s difficult for them and it’s difficult for the teacher, too. Because how do you help a child like that? And if you start something that’s working and then they end up leaving, what’s gonna happen in the other school?

Jose finished third grade with me at Sherwood. After he left my classroom, I think he moved three or four times during the fourth grade. His family had a rent increase so they had to move. Wherever they move, it’s a lower rent, but it’s also less safe. The family witnessed a shooting and got a little scared, so they moved again. Eventually Jose settled down in one location, in an apartment. How long he’ll be there, we don’t know, but he’s been there several years now. He’s an eighth grader right now and doing great.

Over the years, what I’ve done is establish relationships with not just the students but with the entire family in case some of this stuff happens. Jose’s family became one of our adopted families. There’s a group of us former UC Berkeley students: most of us grew up in Hollister, but others we met from San Diego, LA, everywhere. We put money into a pool and we go and buy gifts for our adopted families. For parents it’s mostly gift cards to grocery or department stores. For the kids, we get them the things we never got as children. Like a big remote control car, a skateboard, a bicycle. We really go all out.

I send out a description of the children and their situation. My friends come and we deliver these gifts to the kids. We don’t just go in there and say, “Merry Christmas, here are some gifts.” I explain to them who these strangers are that are with me, where they came from, how they had some of the same obstacles to overcome. And I tell them that the reason we’re here is because we believe in them.

I see some of these kids and think, They are amazing. These are students like Jose, who despite everything they’re going through still have a smile on their face every day and they’re succeeding in school. They want to learn, they want to be there.

An excerpt from Chasing the Harvest: Migrant Workers in California Agriculture, edited by Gabriel Thompson.

All books in the Voice of Witness oral history series are 40% off until Sunday, August 13 at 23:59 PST. Click here to access the discount.

----------

1. From about March to October, most of the nation’s lettuce is grown in the Salinas Valley. Each winter, when temperatures drop, the lettuce harvest shifts to Yuma, Arizona. Many workers shuttle between the two regions, though increased immigration enforcement has caused these numbers to drop in recent years.

2. In December 2015, PBS aired East of Salinas, an hour-long documentary by the filmmakers Laura Pacheco and Jackie Mow, which focuses on the relationship between Oscar and his student.