Tear gas: from the battlefield to the streets

In this excerpt from Tear Gas, Anna Feigenbaum describes the history of the Himsworth Report, used by governments around the world to justify the use of tear gas.

Derry — or Londonderry, depending on which side of “the troubles” your sympathies lie — is located just beside the border that cuts the Republic of Ireland from Northern Ireland. As residents will tell you, “The split name says it all.” While road signs inside the Republic will point you toward “Derry,” those in Northern Ireland direct you to “Londonderry.” Both are constantly defaced, leaving visible layers of the city’s contentious past.

The city’s colonial architecture and unique landscape have shaped the political struggles of its inhabitants for more than four centuries. Between 1614 and 1619, King James I erected city walls of thick lime, earth, and local stone to protect (and partition) Protestant settlers from Irish Catholic rebels — financed by the London businessmen of the Irish Society, chartered in 1613 for economic development via colonial expansion in Ireland.

Outside the city walls was the area now known as the Bogside. Originally underwater, this area gained its name when water levels fell and the river became a stream, eventually allowing structures to be built along the bog’s side. The 1700s and 1800s saw impoverished Donegal families move into the area. They are thought to have been in transit, seeking passage out, but limited finances and few job skills left them stuck in the Bog, in poor conditions. 1 Over time, the population grew younger and the area’s infrastructure older. By the mid-1900s, overcrowding was commonplace throughout the Bogside. Three generations of family could be found crammed into two rooms. “Allegations of discrimination in housing allocations,” a 1967 Royal Commission report read, “exist on a wide scale, particularly where a dispersal of the population would result in a changed political base.” 2

To keep their seats, members of Parliament tried to secure districts by forcing Irish families to remain in the Bogside. A new housing estate, the Rossville Flats, went up, standing ten stories high and housing 178 families. The building’s red, yellow, and blue décor and flat, railed rooftop made it a pillar amid the area’s sunken landscape. Yet this mega-estate was not enough to solve the housing shortage. Plans for more home construction in other wards encountered challenges from the Unionist Corporation, which continued to block progress and to maintain political and economic control of Derry.

Inspired by struggles overseas, particularly in the United States, Palestine, and South Africa, Bogside tenants and local socialists began to organize, forming, among other groups, the Derry Housing Action Committee. “There was high unemployment, no housing program at all, electoral boundaries which hadn’t been expanded, and there was no such thing as one man one vote — there were all sorts of things wrong,” committee member Dermie McClenaghan recalls. 3 The organization began by disrupting housing council meetings. A direct-action campaign soon followed in the flurry of worldwide uprisings across the spring of 1968.

On an unusually clear January day in 1969, unarmed civil rights protesters marched under blue skies from Belfast to Derry. At a bridge crossing just outside Derry’s city center, they were met by loyalists carrying rocks and sticks, who beat them as the police watched, doing nothing. This led to rioting in town, followed by retaliation as loyalists smashed Bogside windows and harassed people in their homes. A few months later, on April 19, threats of violence from loyalist militants persuaded civil rights organizers to call off a scheduled march. Civil rights supporters gathered together in the city square to recuperate, but loyalists pelted them with rocks. This time, the police did not stand by doing nothing. Instead, they charged at the civil rights supporters, batons swinging. Back at the City Hotel, the organizers’ hub, panicked residents were rushing in with reports that Bogside boys were being beaten and unlawfully arrested. Then came the news of Sammy Devenney.

A well-respected middle-aged man in the Bogside, Sammy Devenney was uninvolved in political activity; his home was in the pathway of young rioters. Devenney’s eighteen-year-old daughter Ann remembers the anger in the policemen’s voices as they approached the house: “I could see them, banging at the windows with their batons ... about five or six of them were at the window and they said, ‘We’ll break the effin’ door down.’” The police stormed in. Ann used her body to shield her younger sister, who was recovering from an appendix operation. Out of the corner of her eye, Ann watched as the police attacked her father. “There were three of them at my daddy with batons ... and they kicked him in his stomach and his back and they were just hitting him everywhere.” 4

News of the attack spread through the Bogside. Men rushed from the hotel to the Devenney’s home. They found the door kicked in and the sitting room covered in spatters of blood — walls, chair, floor, ceiling, even across the face of Sammy’s four-year-old son. 5 According to an inquiry report, Devenney was “left lying on the floor with blood pouring from a number of head wounds and with his dentures and spectacles broken.” Less than two months later, the injury killed him. 6

The Battle of the Bogside

Shortly after Devenney’s death came the controversial Apprentice Boys march, an annual commemorative march that carried the legacy of British force in Northern Ireland, complete with loyalist songs, “done with the utmost arro- gance and bravado to show once again who won the battle many years ago.” 7 The parade’s drum and fife bands celebrate Protestant settlers’ defeat of an Irish- and Scottish-led siege on the walled city in 1689.

In the lead-up to the march, a Derry Citizens’ Defence Association formed and met with senior figures of the Apprentice Boys to request the parade be rerouted. Their request was refused. Fearing the troubles to come, some older and younger residents sought refuge outside the Bogside. Barricades went up and calls went out for able-bodied men to come and defend the community. They wove piles of wood and wire modeled after the 1968 barricades of Paris’s boulevards. Young community leader and local MP Bernadette Devlin became a central strategist of the street, directing how to build and where to fortify structures.

On the day of the march, Derry was on edge. Loyalists rounded the city walls, taunting Bogsiders and throwing pennies as insulting symbols of poverty. 8 The Bogsiders stood firm at their barricades. By afternoon, the taunting on both sides turned to stone throwing. As evening fell, the police pushed through the Rossville Street barricade trailed by loyalists, looking like the vanguard of the Protestant militants. Loyalists smashed up windows of the towering Rossville estate, breaching the borders of Free Derry. The Bogsiders shortly regained momentum and, in crowds of a thousand strong, drove the loyalists back to the edge of the neighborhood. 9

At 11:45 that night, Rossville Street became the first UK site of civilian CS gassing. On advice from the Ministry of Defence, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) sought out CS supplies. “We originally had the CN variety,” explain RUC deputy inspector Shillington, “but we have been advised that CS is the more modern and humane type, which in fact is used by the services.” 10 The RUC quickly telephoned the Minister for Home Affairs. While driving from Belfast the Minister approved the deployment. Supplies of CS were brought in from nearby military storage. According to the RUC, the police responsible for discharging CS in the Bogside had received some, “but not enough,” training. 11 Officers were issued 1.5-inch Verey pistols with a seventy- to eighty-yard range for “defense,” as well as canisters to use when withdrawing. All day August 13, they fired CS intermittently in attempts to disperse the crowds. The gas kept coming until 4:30 in the afternoon on August 14. 12

Throughout this bombardment, the Bogsiders retaliated with petrol bombs, stones, and, when available, returned CS cartridges. On the second day of fighting, a group of Bogsiders positioned themselves atop the Rossville Flats. “The high flats was wonderful,” a Bogsider recalls. “But they needed ammunition, so you had to climb eight stories with a bin bag full of stones.” 13 With men and boys perched defensively on the rooftop, older residents gathered in their homes below, creating milk-bottle-bomb assembly lines, stuffing rags, sugar, flour, and wicks into bottles. The flat roof and periphery railing of the Rossville Flats provided an ideal tower-top defense in this otherwise sunken territory: From this perch, the elevated city walls that daily marked Bogsiders’ social and economic exclusions were for once on lower ground. But the Bogside’s depressed landscape also meant that the air could stagnate, CS hung in the area for hours. At other times the gas traveled, rolling with even the lightest breeze. It eased up into the broken windows of Bogside flats. Police also tried to launch CS atop the Rossville estate in efforts to quell the milk-bottle aerial attacks, but few, if any, of the cartridges made it up those ten stories. Instead, they smashed through the windows of residents’ homes.

One of these windows led into the room where a sixteen-month-old infant, Martin, slept. Hearing his baby cry and cough, Martin’s father ran in. He found the room filled with gas. His son was gasping for breath, tears running down his cheeks. His face had gone pale. Martin’s father felt his child might die without attention.

Derry resident Dr. Raymond McClean found himself baffled by the gas’s effects: “Not only were their eyes inflamed and watery, but many of them weren’t able to breathe to such an extent that several were carried in. I didn’t know what we were dealing with.” 14 People didn’t know how to respond. Were they better off opening windows and doors to clear it out, or should they shut them tighter to prevent another round getting in? As its inventors were well aware, gas causes as much psychological fear as it does physical pain.

Those in Derry who had any experience of mass gassing associated the CS with wartime bombings. People dug through their cupboards for old gas masks and distributed them around the streets. However, the old masks offered little protection. Their filters no longer worked and gas often got trapped inside them. In fact, many of the filters were made with asbestos, which is harmful to the respiratory system. Even after they were found to be ineffective, children took to the masks like toys. “We knew they didn’t work,” a Bogsider confesses, “but we liked the way they looked.” 15 These days were full of excitement and fear. “I never slept,” remembers Bernadette Devlin. “For three days and three nights, I was on an adrenaline high.” 16

As the gassing went on, coping tips began to trickle in. A US Army veteran who happened to be in Derry at the time offered advice, typed up in a leaflet that circulated around the Bogside streets. French students in the area are also reported to have taught locals how to flush their eyes out with water and hold vinegar-soaked handkerchiefs to their faces. Devlin recalls, “The whole air was saturated ... and we’d not a gas mask between us ... So we made do with wet blankets, with cotton wool steeped in vinegar, with handkerchiefs soaked in sodium bicarbonate.” 17 One elderly resident stood out on her stoop with a bottle of brown vinegar. As Bogsiders passed by, she poured a drop onto their outstretched handkerchiefs — which in many cases were not handkerchiefs at all but scraps of fabric, and in one boy’s case, an old pair of ladies’ underpants. 18

By the end of the thirty-six hours of CS gassing, a total of fourteen 50-gram grenades and 1,091 cartridges containing 12.5 grams of CS had blanketed the Bogside. This brought a flurry of media attention, with stories like baby Martin’s causing moral panic to ripple through the country. Facing a PR disaster, the Home Office had to act quickly, setting up yet another tribunal to look into Northern Ireland’s most recent disturbances and announcing that a full medical investigation would be conducted into the effects of CS gas in the Bogside.

The Chemical Defense Establishment

Sir Harold Himsworth, a physician in London, was appointed to lead the medical investigation. Himsworth, an advocate of fusing the skills of politicians and scientists, had served as secretary to the Medical Research Council and presided over the Section of Experimental Medicine at the Royal Society of Medicine. In 1952 he was knighted into the Order of Bath for his contributions to civil service. 19 A 1958 New Scientist article profiling Himsworth’s accomplishments called him a man of undoubted authority, “receptive, courteous and decisive.” 20

On September 1, 1969, Himsworth and his team arrived in Belfast. Their first stop was the Ministry of Health, where they were briefed on events in Derry by a group of Belfast doctors and government officials. They headed to the GOC Army headquarters for an “off the record” interview with Sir Ian Freeland, director of operations in Northern Ireland, and a briefing on the situation from a brigade commander. This was followed by another press conference in which Himsworth insisted that “there was nothing sinister in the use of CS gas.” 21 Himsworth was “kindly loaned” the Army’s Public Relations Officer, and by the end of the evening the team had additionally secured help from Colonel Millman, who “prof- fered any assistance within his power.” 22

On day two, Himsworth’s committee ventured into the Bogside. Picking their way over rubble and through the ruins of barricades, they were quickly surrounded by locals anxious to tell their stories. They questioned a girl clutching a teddy bear as her mother explained the persistence of her sore eyes and lips. Derry doctor Donal McDermott related that “scores of people had suffered from vomiting, diarrhea and nausea.” 23 A fifty-five-year-old resident reported that her pet budgie had died in its cage; others shared stories of how children’s suffering appeared more acute than adults’. Confused, scared youngsters often rubbed their eyes, worsening the effects. The committee canvassed the area, examining the Rossville Flats and CS cartridges saved by the Citizens’ Association. Himsworth expressed skepticism over media claims that there had been sixty to a hundred cases of gastroenteritis and diarrhea. If this were true, he argued, it should have been officially classified as a major crisis; illness at this scale required government notification. What he didn’t see was that, in the middle of a riot, people’s fears of arrest and the frenzy of the commotion bar many from seeking hospital treatment. Even under normal conditions, people in impoverished areas are reluctant to go to hospitals or doctors for digestive problems, preferring to tough it out or use home remedies, but in a city divided along religious, political, and economic lines, seeking formal medical care was even more contentious. This city of two names was also a city of two hospitals: The nearest was staffed by Unionist doctors, and many Bogside residents avoided it, opting instead to cross the border into Ireland and receive treatment there.

Most medical treatment during the Battle of Bogside happened in the Candy Corner shop at the top of Westland Street. Off-duty nurses and medics set up a treatment post inside the store. Dr. Raymond McClean’s wife Sheila drove over the bridge to the hospital for antiseptics, dressings, and suturing supplies. The Candy Corner first treated casualties from stone throwing and street fights. After the gassing began, the makeshift medical staff treated lacerations, concussions, and head injuries from CS cartridges, including a young man whose nose was nearly severed off his face. They worked without adequate space or equipment. As gas casualties poured in, volunteer nurse Attracta Bradley recalls, “We really were at a loss on what way to treat it because we’d really been taught basic first aid. We’d never been taught how to manage tear gas.” 24 The staff spent over twenty-four sleepless hours tending the CS victims. Then tear gas crept into the Candy Corner as the police advanced, forcing the medical team to relocate. Supplies in hand, they carried the sick up the hill to Creggan, where they re-established the first-aid center in the local Boys’ Club until the gassing finally ceased. 25

Amid these riotous conditions it is difficult to imagine how standard hospital notification procedures would be carried out. But Himsworth, a man of record, sought statistics. He was after authorized laboratory reports, not regular people’s tales of gassed babies or dead budgies. Throughout his diary of the visit, he records residents’ stories of their experiences and effects with suspicion and occasionally derision. For example, a physician at Altnagelvin hospital reported the case of chronic asthmatic Charles Coyle, age fifty. The committee recorded in their notes that the man:

had been getting steadily worse for some years. His story (typically Irish) was that on the night of 12 August he was on the city wall when CS gas was dropped some two or three hundred yards in front of him—he walked up to it and sniffed it. Feeling ill he went into the O’Range Hall where we stayed for a while. He then came out and got another whiff of the gas but walked half-a-mile home. For four days afterward he stayed at home, but didn’t see a doctor.

While it is unclear whether it was Himsworth, his secretary, or the doctor who found this case to be “typically Irish,” the comment’s documentation in a formal log signifies the disposition of the “independent” British investigation toward the civilians whose health and well-being they were documenting. Such prejudices matter. Himsworth’s rationalist approach and determination to keep questions of human conditions apart from scientific observations significantly shaped his findings. While personal details like Martin’s father’s fear that his infant might die were quickly dismissed, here the personal was placed in support of a medical description. If Himsworth’s observations had been explicitly acknowledged as military research, these biases could be traced to their root, making accountability easier to map. The problem lies in the claim that this enquiry was independent. The rhetoric and “off the record” meetings masked the team’s deeper connections to the government and military from public view. Their medical research was financed and authorized by the Home Office; the majority of guidance coming in on the ground in Derry was supplied by the military and police. Later, the Ministry of Defence’s Chemical Weapons branch became the key source of experimental data. This kind of scientific bias leads to partial pictures: People’s experiences get cut up and rearranged into government-sanctioned shapes. As with the chemists of World War I, who perfected their poisons to gain prestige, when clinical tasks trump human accountability, atrocity — however unintentional — often follows.

Himsworth’s committee traveled directly from Northern Ireland to Porton Down, the MoD’s chemical testing facility. Nestled within sixteen acres of countryside, Porton Down was a top-secret station for military research and weapons development, running throughout World War II and the Cold War period and continues to be so in the present day. An estimated twenty thousand military “volunteers” went through the facility, many as subjects in experiments on chemical agents. Told that the military was testing treatments for common colds, volunteers were guaranteed safety and given shillings for participation. As Rob Evans uncovered in researching his book Gassed, “They wanted to get away for any type of break, just anything ... But sadly very few actually knew what Porton Down was, or what they were letting themselves in for.” 26

Some of the chemical agents tested on these young men and women included the nerve agent sarin, different mustard gases, and lachrymators — tear gases — as well as other kinds of chemicals, like smoke bombs and dyes. There were skin tests, oral tests, tests of irritants on the eyes, behavioral tests, and gas-chamber tests, among others. “It was hideous,” according to retired officer Patrick Mercer, “a hutted camp, where it seemed to do nothing but rain. There were a series of bunkers to which you were thrust from time to time to be gassed with CS and to go through ghastly exercises underground wearing a gas mask.” 27 Between 1941 and 1985, approximately 8,850 tear gas tests, mostly of CN, CS, and CR agents, were conducted on more than 2,800 veterans. 28 The development of CS as a riot-control agent began in the 1950s and increased in the 1960s as unrest in Northern Ireland grew.

When Himsworth arrived at Porton Down in 1969, the facility was known as the Chemical Defence Experimental Establishment, shortened the following year to the Chemical Defence Establishment (CDE). This secretive testing site has undergone eight name changes and numerous structural re-organizations in its near-century of operation. Today it is called the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory. In the late 1990s, a large-scale probe was launched into the human experiments at Porton Down. Veteran Gordon Bell, supported by others, initiated the enquiry. Between 1959 and 1960 Mr. Bell had undergone three tests, including one with sarin and another with CS. His multiple requests for information regarding his records were refused. Determined to hold the government accountable, Bell continued to pressure law enforcement and government authorities to hold a formal investigation.

At a late-night House of Commons session in 1998, South Sutherland MP Chris Mullin raised Bell’s concerns before the Minister for the Armed Forces. “Not for the first time in matters of this nature, there is a feeling that the Ministry of Defence is being economical with the truth,” Mullin said. Citing similar claims brought forth to the House by Bournemouth veterans in 1996, Mullin insisted that Bell was not alone in his recollection of the experiments at Porton Down. This was not a case of retrospective blame, he argued. Rather, it suggested an intentional cover-up:

Many of those experiments and the manner in which they were conducted would have raised concern even by the standards of the 1950s—more so, in fact, as the experiments carried out by the Nazis that prompted the Nuremberg code were fresh in the public mind in the 1950s ... I put it to the Minister [for the Armed Forces] that those who were the subject of the experiments at Porton Down were not told the truth precisely because it would have been unacceptable even by the standards of the time. 29

But in 1969, when Himsworth visited, all of this had yet to be exposed; the chemical testing facility was running business as usual, operating on what Grimley Evans describes as “wartime ethics.” In an atmosphere of perceived imminent attack, utility reigns supreme and military secrecy often overrides informed consent. On top of this, Porton Down was run by a mixed civilian and military staff. This created levels of secrecy and security clearance that made it difficult to practice any one protocol. It was hard to determine fault when things went wrong. 30 Such claims to layers of organizational complexity tend to evaporate accountability in what Linsey McGoey has called “strategic ignorances.” 31 The atrocity at Porton Down was not only the procedure, but the value system. What — and who — made it an issue of scientific importance to directly apply known poisons to people’s skin, lungs, and eyeballs without consent?

The results of the Porton Down experiments played a key role in the Himsworth Committee’s report. Between October 1969 and March 1971, Sir Himsworth and his team held a series of meetings at Whitehall in which they shared scientific findings, correspondence with medical professionals, and laboratory evidence. Their priorities included finding evidence of CS’s effects on the young, the elderly, and pregnant women, as well as people with previous illness. Himsworth also asked the committee to investigate cases of chemical manufacturers repeatedly exposed to CS and to gather “full details of the Vietnam experience.” 32

Conspicuously absent from the agenda was any reference to the United States’ widespread use of CS and other tear gases to combat civil protests. Himsworth was silent on the crushed labor strikes, civil rights struggles, antiwar protests, and even the helicopters that sprayed CS over thousands on the Berkeley campus just four months before the team’s first meeting, all of which were heavily publicized in the United States and discussed at UN meetings on the Geneva Protocol. The Geneva Protocol bans the use of chemical and bacteriological weapons in war. The United Kingdom and the other European Allies had signed onto the agreement in 1925. While the United States was instrumental in bringing the protocol forward and President Roosevelt made appeals to it during World War II, the United States did not ratify it until modifications were made in 1975. This position garnered international attention during its widespread use of chemical weapons in Vietnam. In 1966, the Hungarian delegation, backed by other Eastern European nations, put the matter back on the UN’s agenda. “The hollow pretexts given for using riot-control gases in Vietnam,” the Hungarians argued, “have been rejected by world public opinion and by the international scientific community, including scholars in the United States itself.” Appealing to the Geneva Protocol, Hungary called for the use of chemical weapons to constitute an international war crime. 33 One prominent US scholar who rejected the use of riot-control agents in Vietnam was Nobel laureate and Harvard professor George Wald, who attested that “under combat conditions, tear gas is part of a thoroughly lethal operation.” 34 But the US delegation continued to argue that the Geneva Protocol should not prohibit riot-control agents, a position that garnered UK support.

Tear Gas as a Drug

Amid increasing counterinsurgency efforts in Northern Ireland and in light of these international debates, in February 1970 British foreign secretary Michael Stewart drew on the Himsworth Committee’s interim report to announce a new stance: “CS smoke is considered to be not significantly harmful to man in other than wholly exceptional circumstances; and we regard CS and other such gases accordingly as being outside the scope of the Geneva Protocol.” 35 This announcement led to uproar from members of Parliament, NGOs, antiwar groups, and UN delegates.

In June 1970 Sir Alec Douglas-Home took over as Foreign Secretary. While he had reservations over this policy change, the MoD was adamant that CS fell outside the Protocol’s restrictions, which deal with substances that were “significantly harmful or deleterious to man — an argument which it rejected.” 36 In addition, if the government were to deem CS deplorable in war, it would be difficult to justify its domestic use as a means of crowd control. The MoD appealed to the “smoke’s” pacifying powers: “CS has saved innocent lives and gave the police and army a much more humane option than batons, bayonets and bullets or bombs.” 37 This position would soon be validated by the Himsworth Committee, which posited that the effects of CS should be considered “from a standpoint more akin to that from which a drug is regarded than from that from which we regard a weapon.” 38 This framing worked to partition the team’s enquiry from concurrent debates over international law happening in Parliament; it was crucial that the public not be led to translate the ethics of combat to the domestic “troubles” in Northern Ireland. These guidelines, given by the Home Office, delineated a particular relationship between humans and tear gas. It asked the scientists to find a way to calculate safety, to measure it in doses. With drug tests in mind, the Himsworth Committee proceeded to consider CS’s effects with the ultimate aim of authorizing its use.

The government, like a drug company trying to push its product to the market by funding its own research, had employed Himsworth and his team as stakeholders; its members had vested interests in the research and development of this chemical agent. Dr. John Barnes, the committee’s technical advisor, worked in a research capacity for the Ministry of Defence throughout his time on the independent enquiry team. At the very first committee meeting Dr. Barnes raised the issue, “to be quite sure that it was appreciated that he was the Chairman of the Biology Advisory Committee of the Chemical Defence Advisory Board.” Sir Himsworth promptly reassured him: “The Committee is an independent body charged to make an independent investigation and to report to the Home Secretary.” The committee members were “to have no special relations with any other advisory bodies.” Requests for evidence should be made in the same way, whether from government departments or private individuals. 39 Moving between abstract independence and practical allegiance, Himsworth’s attempts to remain above bias were questioned by his own team.

In the final committee report, the team drew attention to some of the problems arising from their task: What did it in fact mean to consider a weapon as a drug? How could safety be measured medically? Investigating CS as a “druglike” substance required two key considerations. First, they had to determine what distinguished a safe dose from a dangerous dose; and to ask whether the difference was great enough that the drug could be certified as safe. Second, they had to examine the side effects. Were they too great to outweigh the drug’s benefits?, “CS is usually used not in relation to a particular single individual, but in relation to a population,” they noted; during a civil disturbance, it is not only “healthy young adults” who face gassing. CS can affect anyone in the vicinity, including “children, the old, pregnant women and the ill, who are exposed inadvertently.” 40 Determining safety and risk in these circumstances, the committee pointed out, was both medical and political.

Unlike most drugs, CS is not administered in a controlled oral or topical dose. It is no antibiotic tablet or eczema cream. Deployed as a fog or smoke, CS consists of tiny droplets that are absorbed through the skin and inhaled through the lungs. Its effects vary with weather conditions, topology, spatial structures, pre-existing medical conditions, and personal tolerance levels. These factors make it difficult to determine the exact level of a “dangerous dose.” But “by Command of her Majesty,” Himsworth and his team accomplished just this.

The Himsworth Report

The committee presented clinical, experimental, and observed evidence, doing their best to bracket off any “element of emotion” from their presentation of findings. Extrapolating from animal experiments, since human experience could not be trusted, the Himsworth Committee listed and refuted side effects, detailed dangerous doses, and offered operational guidance. In the end, CS got its clearance for use during civil disturbances. It was labeled safe for the young and old, as well as pregnant women; some warning was given that it should be used with strict guidance in enclosed locations. 41

Derry doctor Raymond McClean, a prominent figure in Derry’s nascent civil rights struggles who went on to become mayor, met Himsworth during the committee’s whirlwind tour of the Bogside. They dined at the Broomhill Hotel, accompanied by McClean’s wife Sheila, a local art teacher, and Himsworth’s secretary, Major Snowden. Sheila spoke with Himsworth at length about literature and politics. While Raymond found Himsworth affable, he sensed that Himsworth was a “grey areas man” — a feeling that later proved all too true.

McClean wrote to Sir Himsworth, “I have discussed your taste in literature with my wife Sheila on many occasions since our last meeting. Apparently she has some understanding of how an intelligent, educated, sensitive person can be interested in injustice and brutality only on some higher plane. I must admit that this understanding has not been given to me.” 42 The two men corresponded during the production of the committee’s report. At the Candy Corner medical station, McClean had treated CS patients with epilepsy who were “carried into the medical centers in a state of collapse and rigor.” Himsworth’s team declined to look into CS’s effects on epilepsy, concluding instead that “during the period of excitement [epilepsy patients] may have omitted to take their drugs.” Furious, McClean wrote in haste to the British Medical Journal objecting that this claim had no scientific merit. Privately, he wrote to Himsworth, “I was ashamed for you when I read the committee’s comments on epilepsy.” 43 He also challenged the report’s evaluation of CS as a drug, questioning how the political situation in Northern Ireland could be reduced to a set of side effects and insubstantial sociological factors. Drawing on his own experiences of increasingly violent repression and internment in Northern Ireland, McClean spread word that “the real purpose of this report must remain in serious question.” 44

McClean was far from alone in his objections. Two years before the final report was released, the British Society for Social Responsibility in Science (BSSRS) preemptively criticized the enquiry, arguing that it was important for the committee to look beyond the clinical and include social scientists’ perspectives “if it is to make the necessary inquiries about the effects of the use of CS gas — not merely on the eyes and lungs of those who consulted doctors, but on the whole group of people affected.” 45 In 1970, the magazine New Society published a very different picture of the effects of gas in Derry. Unlike Himsworth’s team, the BSSRS sought to understand the informal medical care provided during the Battle of the Bogside. While for Himsworth Derry residents’ lack of hospitalizations was evidence that few people needed medical care, the BSSRS researchers recognized that at times “there were too many causalities to count” seeking treatment at makeshift first-aid stations that had to be repeatedly cleared from CS contamination. 46

Himsworth had rejected the prospect of carrying out an epidemiological investigation like that proposed by the BSSRS, arguing that widespread questioning “would certainly cause alarm and the retrospective replies obtained would be of very dubious value.” 47 He arranged for BSSRS representatives to give evidence at a committee meeting, but ultimately dismissed their reports as unsubstantiated sociology. 48 Indeed, over the course of the investigation Himsworth created doubt around a number of findings and observations, including those of Professor Francis Kahn from the Sorbonne. In 1966 and 1967 Kahn had traveled to Vietnam to investigate the effects of chemical gases on the civilian population and brought back samples from Tay-Ninh that he had collected from an 801b barrel “with a mask and many troubles.” 49 During his travels Kahn had been shown footage and told anecdotes by Vietnamese doctors and local people of deaths resulting from tear gas. CS grenades were being fired into shelters and tunnels where Vietnamese families were hiding.

While the US Army claimed to be using only CS, many questioned that this chemical agent alone could cause death. The final Himsworth report also raised doubts, noting that Professor Kahn “had no first hand contact with cases there” and that death by asphyxiation could not be directly faulted to CS. The committee suggested that the Vietnamese people’s behavior had led to their own deaths: burrowing into makeshift bomb shelters in efforts to escape the poisons shot from the sky, some ended up starved of oxygen while hiding inside. 50

In addition to his research in Vietnam, Kahn also investigated the use of CN and CS (called CB in France) during the May 1968 uprisings in Paris. Kahn was a member of the Union of University Teachers and stood on the front lines during the student protests. From within the crowd, he observed cases of panic, eye lesions, and unconsciousness. Professor Kahn also shared the case of Madame Macina, an older woman with a respiratory condition who had died after being caught up in clouds of tear gas. No autopsy was done and she was legally declared to have died of natural causes. Unsatisfied, Professor Kahn attempted to discover more; however, as he explained in a letter to Himsworth, “when we tried to go on in the study of this case, we faced problems since the witnesses, including her doctor, the drivers of the ambulance and her own family did refuse to give us further details.” The professor presumed this was because of “hard pressure from the police.” 51

The Himsworth Report noted this case, but made no mention of Kahn’s comments on the difficulties of obtaining evidence:

The subject was an elderly woman who was known to suffer from a chronic illness that caused shortness of breath. Despite this, she took an active part in the disturbances of the 6th May ... Toward the end of the day she got increasingly breathless and in the evening become so ill that she sent to hospital. She was dead on arrival ... in view of her previous illness, death was certified as due to natural causes. Clearly the medical man concerned felt justified in believing that her death was related to her pre-existing condition. In the absence of further evidence, we can only accept this. 52

Sterilizing the enquiry process from emotion, politics, and personal experience helped Himsworth construct a tidy report, but the scientific method alone could not be trusted to sift through all the laboratory results. The team needed to make sure the press did not get hold of any unappealing experimental data before the publication of the report. During the committee’s eighth, ninth, and tenth meetings, a number of experiments arose showing more severe effects of CS. With mounting pressure to deliver the final report, the chairman had to decide how to handle these unpublished experiments, which became known as the Porton Papers. The committee agreed that the Porton Papers would not be sent out for publication in scientific journals until three to six months after the report was published, as the papers “could be used by hostile parties to confuse the lay public.” 53

Ultimately, the Himsworth Report trumpeted experimental results over medical observations and continually down- played the significance of personal testimony. Personal details on patients were only included when it served to mitigate the ill effects of CS, as in the case of Madame Macina, Vietnamese peasants, and the Bogside father of baby Martin. Likewise, social scientists’ claims that CS effects must be considered in their economic and political context were bracketed at the very outset from debate. Suggestions that the psychological conditions of riot situations could have physiological impacts were brought up in the final report, only to be separated out from the “real effects” of CS. The report treated bodily reactions as side effects; as if they were the result of personal dysfunctions or rare allergies to an everyday product, rather than human bodies responding to poisoned air.

Domestically, the Himsworth Report’s stamp of approval freed Britain to further develop more deadly riot-control agents, counterterrorism technologies, and counterinsurgency tactics — using Northern Ireland as a testing ground. Throughout the 1970s, tensions, between the military, police, loyalists, and Irish protesters escalated. CS gas became so commonplace that families lined their front doors with towels to stop it from seeping in. It was frequently fired at close range and into enclosed spaces. On one occasion police fired CS into a bus full of people. 54 Political prisoners were frequently gassed, with rights groups claiming that the stronger lachrymatory agent CR was sprayed during the Long Kesh riots in 1974, causing lesions and permanent scarring. In many ways the birthplace of modern notions of “nonlethal” weapons, Northern Ireland was also home to the first use of rubber-coated metal bullets. The year 1978 brought the use of plastic baton rounds (also called plastic bullets), which were made available to police and soldiers. During the 1981 political prisoners’ hunger strike 29,601 rounds were fired at demonstrators, resulting in seven deaths. Eight years later the official death toll from this “nonlethal” technology reached seventeen. 55 Now deployed around the world, different kinds of impact munitions, commonly referred to as rubber bullets, are frequently fired through clouds of tear gas.

The Himsworth Report continues to be used by governments around the world to justify the use of tear gas. In 1989 the US State Department invoked it to defend exporting $6.5 million worth of tear gas guns, grenades, launchers, and launching cartridges to Israel. This tear gas was thrown into Palestinian houses, clinics, schools, hospitals and mosques, often in residential areas, by IDF forces in the Occupied Territories. Human rights groups recorded up to forty deaths resulting from tear gas, as well as thousands of cases of illness. The State Department, facing criticism, cited the Himsworth finding that “the margin of safety in the use of CS gas is wide” and concluded that suspending tear gas shipments “would be inconsistent with US efforts to encourage the use of restraint by Israel and could work to the disadvantage of the Palestinian population in the Occupied Territories.” 56

In 1993, the Himsworth Report surfaced again, making its way into hearings on the FBI and military siege of the Branch Davidian religious complex in Waco, Texas, which left dozens dead. Congressman Sonny Bono stared down his gold-rimmed glasses at Attorney General Janet Reno: “Your decision to approve of gassing the Davidians with the CS gas was based on Dr. Salem’s advice on the report prepared by the British research team?” “I believe it’s referred to as the Himsworth report,” Reno replied. 57 After hours of intensive scrutiny by the congressional committee. Reno, who had been a chemistry major at Cornell University, sanctioned the deployment of CS gas over a forty-eight-hour period in efforts to end a fifty-one-day standoff between the religious sect and law enforcement.

Strategists hoped the gas would cause leader David Koresh and his followers, who had twenty-two children among them, to exit the compound. But instead of clearing people out, the gas brought returned gunfire. The women and children barricaded themselves even deeper inside. Within hours, the entire structure went up in flames. Seventy-six people were later found dead inside. 58 The effects of CS gas on those who died at Waco were obscured by the flames; autopsy reports listed the cause of death in most cases as asphyxiation or falling debris. The ethical questions surrounding the FBI’s use of CS against protocol were briefly raised by media critics and members of the congressional committee, but in the end were largely eclipsed by the fire in the public memory.

Despite a long trail of reports of CS harms that came throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, it was Himsworth’s report that remained the technical trump card. Every major inquest or “independent enquiry” conducted in the decades to follow re-established its prominence through processes of expert testimony and citation. These official inquiries worked to maintain dominant structures of scientific knowledge production, affirming the central authority of military research centers and handpicked, government-approved scientific experts. In this system of scientific capital, researchers are encouraged to exchange stamps of safety for professional prestige. With government safety clearances in place, it was time to roll out tear gas in England.

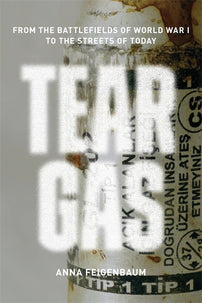

This essay is excerpted from Tear Gas: From the Battlefields of WWI to the Streets of Today by Anna Feigenbaum.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]More than a hundred years ago, French troops fired the first tear gas grenades at the German enemy. Designed to force people out from cover, tear gas causes tearing and gagging, burning the eyes and skin. Its use has ended in miscarriages, permanent injuries, and death. While all but a few countries have agreed that it is illegal to manufacture, stockpile, or use chemical weapons of war, tear gas continues to proliferate in civilian settings. Today, it is a best-selling form of “less lethal” police force. From Ferguson to the Occupied Territories of Palestine, images of protesters assaulted with “made in the USA” tear gas canisters have been seen around the world. The United States is the largest manufacturer, and Brazil and South Korea are rapidly growing markets, while Britain has found an international audience for its riot control expertise.

An engrossing century-spanning global narrative, Tear Gas is the first history of this poorly understood weapon. Anna Feigenbaum travels from military labs and chemical weapons expos to union assemblies and protest camps, drawing on declassified reports and eyewitness testimonies to show how policing with poison came to be.

Notes:

1. Museum of Free Derry, “Battle of the Bogside,” n.d.

2. London Times, “Ulster Investigation Urged by Labour MPs,” April 26, 1967.

3. Freya McClements, “The Day that the Troubles Began,” BBC News, October 3, 2008.

4. Ann Devenney also flung herself over her father at one point during the attack and was kicked and forcefully pulled from him. She recalls watching the police beat her younger siblings, including a four-year-old and a ten-year-old. See her 1969 interview, Micky K (YouTube user), “Devenney Interview 69,” YouTube video, posted May 9, 2009, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-exjygMKmxs.

5. Raymond McClean, The Road to Bloody Sunday (Dublin: Ward River Press, 1983).

6. Although an investigation was conducted at the time, the results of the Drury report were never shared with the Devenney family. It was not until a complaint was upheld in 2001 that responsibility for the death of Sammy Devenney at the hands of RUC police was formally and publicly acknowledged. Police ombudsman, “Police Ombudsman Releases Findings on Devenney,” press release, October 4, 2001, http://www.policeombudsman.org/ Publicationsuploads/devenny.pdf.

7. Deane-Drummond, Riot Control.

8. Russell Stetler, The Politics of Violence in Northern Ireland (London: Sheed and Ward, 1970).

9. Museum of Free Derry, “Battle of the Bogside.”

10. Tim Jones, “Police defend use of smoke,” London Times, August 14, 1969.

11. Harold Himsworth, “Diary of Visit to Northern Ireland,” PP/RHT/C1 Himsworth Collection, Wellcome Trust.

12. Ibid.

13. Battle of the Bogside, dir. Vince Cunningham, 2004.

14. Ibid.

15. Bogside Artist Collective, author interview, Derry, January 8, 2013.

16. Battle of the Bogside.

17. Bernadette Devlin, The Price of My Soul (New York: Pan Books, 1970), 203.

18. McClean, Road to Bloody Sunday; Interview with Bogside artists.

19. John Gray, “Obituary: Sir Harold Himsworth,” Independent, November 9, 1993.

20. New Scientist, “Profile: Sir Harold Himsworth: His Inspiration Was the Family Doctor,” October 30, 1958: 1161–2.

21. Himsworth, “Diary.”

22. Ibid.

23. Tim Jones, “Bogside tells inquiry team of gas effects,” London Times, September 3, 1969.

24. Battle of the Bogside.

25 McClean, Road to Bloody Sunday.

26. BBC News, “Porton Down—A Sinister Air?” August 20, 1999.

27. Ibid.

28. Keegan et al. “Exposures recorded for participants.”

29. Commons Hansard Debates, text for March 17, 1998. A formal enquiry began in 1999. Its outcome validated veterans’ claims to the nature of testing and the lies told to them by the government that garnered their participation. Out-of-court settlements saw some compensation and apologies provided to veterans’ families, but there have been no criminal convictions.

30. Tal Bolton, “Putting Consent in Context: Military Research Subjects in Chemical Warfare Tests at Porton Down, UK,” Journal of Policy History 23(1), 2011: 53–73.

31. Linsey McGoey, “The Logic of Strategic Ignorance,” British Journal of Sociology 63(3), 2012: 533–76.

32. Himsworth Committee, minutes of first meeting, October 4, 1969.

33. International Committee of the Red Cross, “Hungary: Practice Relating to Rule 74. Chemical Weapons,” n.d., icrc.org.

34. United Nations, Chemical and Bacteriological (Biological) Weapons and the Effects of Their Possible Use (New York: Ballantine Books, 1970), xv.

35. John R. Walker, Britain and Disarmament: The UK and Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Weapons Arms Control and Programmes, 1956–1975 (London: Ashgate Publishing, 2012), 35.

36. Ibid., 33.

37. Ibid., 33.

38. Himsworth Committee, minutes of third meeting, December 11, 1969.

39. Himsworth Committee, minutes of first meeting.

40. Parliament, Report of the Enquiry into Medical and Toxicological Aspects of CS (Her Majesty’s Stationary Office: London, 1971).

41. Ibid.

42. Personal correspondence, October 20, 1971, Wellcome Trust.

43. Ibid.

44. McClean, Road to Bloody Sunday.

45. Ibid.

46. Hilary Rose and Russell Stetler, “What Gas Did in Derry,” New Society, September 25, 1969.

47. Himsworth Committee, minutes of first meeting.

48. Parliament, Report of the Enquiry, 20.

49. Personal correspondence, Kahn to Himsworth, [1970 Wellcome Trust PP/HPH/C/6.

50 Parliament, Report of the Enquiry, 21.

51. Personal correspondence, Kahn to Himsworth, March 8, 1970 PP/HPH/C/6.

52. Parliament, Report of the Enquiry, 21.

53. Himsworth Committee, meeting minutes, March 23, 1971, Wellcome Trust.

54. On January 30, British violence against Irish demonstrators took a dark turn. During a peaceful civil rights march in Derry, the British military fired live finger-length bullets repeatedly into crowds of protesters. They killed fourteen men and boys — six of them only seventeen. The bullets were so powerful and had been shot at such close range that in some instances they cut straight through one person’s body and into another. The events of this day are infamous as “Bloody Sunday.” Further immortalized by Bono in U2’s 1983 hit song “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” January 30, 1972, became the best recorded and most remembered moment of the Irish civil rights struggle.

55. Colin Burrows, “Operationalizing Non-Lethality: A Northern Ireland Perspective,” in. The Future of Non-Lethal Weapons: Technologies, Operations, Ethics, and Law, edited by Nick Lewer (Hove, UK: Psychology Press, 2002).

56. Government Accountability Office, “Use of US-Manufactured Tear Gas in the Occupied Territories,” April 13, 1989, NSIAD-89-128.

57. House Committee on Government Reform and Oversight. Subcommittee on National Security, International Affairs and Criminal Justice, “Waco Investigation Day 10 Part 3,” House Oversight Committee hearing, YouTube video, filmed August 1, 1995, posted January 1, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch? v=OhjhRehknZA.

58. Frontline, “Waco: The Inside Story,” online repository, PBS, 1995–2014.