The Whole World Is Watching

While delegates made their way to Chicago for the 1968 Democratic National Convention, tens of thousands of protesters were set to converge in the city for a week of civil disobedience. Protesters, passersby, and even residents out on their porches were beaten. The chasing, swinging, and clubbing was indiscriminate. Journalists, denied any special treatment, were battered and taunted, at times even targeted.

Today's riot control tactics have a long history. In 1968 police used tear gas and excessive force to break up peaceful protestors at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago; we see those same tactics in our streets today as police violently engage with people protesting the racist police killing of George Floyd and countless Black people.

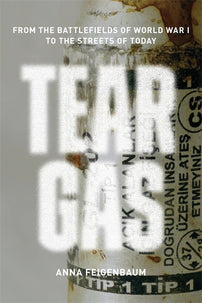

An excerpt from Tear Gas: From the Battlefields of World War I to the Streets of Today by Anna Feigenbaum.

While delegates made their way to Chicago for the 1968 Democratic National Convention, tens of thousands of protesters were set to converge in the city for a week of civil disobedience. Yippies, hippies, clergy, veterans, student activists, civil rights groups, Black Panther Party members, and moderates against the war were all on their way. From their office on the Loop, thirty staff members of the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam, known more casually as “the Mobe,” organized housing, legal defense, first-aid squads, and alternative media publishing. To top it off, a garbage strike had just ended and a taxi strike, was just beginning, to be followed by a wildcat bus strike. Temperatures and tensions were rising.

It had been just over four months since Chicago was rocked by riots following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. On the South Side, twenty city blocks had been lost to fires. Break-ins, looting, arson, and property damage were widespread, and whites and business owners were fleeing the neighborhood. Daley had called in the military to put down the rioters. Twelve thousand army troopers and 6,000 National Guardsmen took over the streets. By the end of the unrest, 500 people were injured and nine dead.21 “They were all black men, ranging in age from 16 to 34,” writes journalist Christopher Chandler, evoking their memory beyond these lifeless figures. “Four were married. Eight were employed. Seven had been shot to death. Another died in a fire and the ninth bled to death from a cut on his leg.”22 Mayor Daley had given remit to “shoot to kill,” and shoot to kill some had.

Now Mayor Daley was making his own preparations. He was not about to let the city fall out of his control again. Chicago’s 12,000-strong police force was placed on twelve-hour shifts and a curfew was put into effect. Six thousand National Guard and 6,000 troopers were called in for reinforcements, all loaded with the newest military-grade riot-control equipment.23

On Monday night, protesters in Lincoln Park were prepared to resist eviction come curfew time. They assembled a makeshift barricade out of garbage cans and park benches. Hundreds of officers were on hand and equipped to stop the demonstration with force if necessary, periodically giving loudspeaker announcements for the remaining protesters to leave. An estimated thousand protesters remained. Some prepared for tear gas by smearing Vaseline on their faces and covering their mouths with wet clothes. Others held rocks and small projectiles to throw back at police lines. Trash fires burned along the barricade and occasionally a rock was hurled against a police-car window.

The protesters’ chants mocked the police. Their anger floated on the summer air along with the sound of trashcan drums and Allen Ginsberg’s group chanting om. A police car entered the park from the back and protesters pelted it with stones. Tensions were rising and at 12:30 the police issued their final warning to evacuate the park. Then came the tear gas:

Tear gas canisters were plummeting everywhere behind the barricade, through the trees. A huge cloud of gas rolled over the barricade, and cops with gas masks came over the barricade in an assault wave, with shotguns and rifles and using the butts as clubs on anyone in sight.24

Protesters, passersby, and even residents out on their porches were beaten. The chasing, swinging, and clubbing was indiscriminate. Journalists, denied any special treatment, were battered and taunted, at times even targeted.25 The tear gas kept coming:

Gas! Gas! Gas! was the cry, as if poisonous snakes had been loosed in the area … Thousands streamed across the park toward Clark Street, and panic started, headlong running, the sudden threat of being trampled by your own people … The tear gas was catching up with us, a sharp menthol sort of burning on the cheeks and burning in the eyes, but though some people ran from it, most of us kept on just walking … Now the tear gas began really burning, making the eyes twist tightly closed, and if you rubbed it the burning got worse, as if your eyeballs were being rolled in fire.26

Tear gas seeped into homes, cars, and restaurants. It covered whole city blocks, taking over the air. The following night, tear gas was once again used to clear demonstrators from the park at curfew. Historian Frank Kusch writes that a sanitation truck joined the police lines. “The bed of the truck held a tear gas dispenser and a large nozzle for dispensing the gas—all requisitioned from the army. Two police officers manned the nozzle.” Additional gas was fired into the remaining crowd as officers in gas masks forced protesters onto neighboring streets. Some fought back, throwing rocks and bottles.27

Wednesday brought tear gas to the Hilton, the temporary residence of many of the conventions delegates and journalists as well as some Mobe members. A rally by the Grant Park bandshell was the only permitted protest event of the week. It drew a crowd of ten thousand. At the end of the rally demonstrators wanted to march to the bandshell, but the police and National Guard blocked off the rally at three exit points, following orders to contain the protesters or disperse them away from the convention sites.

Then came the incident with the flag—a moment reported and recorded in a variety of versions. What witnesses seem to agree on is that news came back from the convention hall that the antiwar candidate for the Democratic nomination, Eugene McCarthy, had been defeated by Vice President Hubert Humphrey, despite the popular vote favoring McCarthy. Disappointed by the vote, protestors called to lower the park’s flag to half-mast. In the commotion another flag was raised—and it was red. Whether it was a Communist flag or a pair of Yippie trousers depends on who you ask. Either way, it went up, and violence erupted as police fought their way into the crowd, beating people as they went. This sent the thousands of people in the park looking for a way out, but police and Guardsmen blocked the exits. Volleys of tear gas were fired into the crowd:

Eyes burning, lungs filling with this corrosive stuff, throats feeling as though we had swallowed steel filings, hundreds of demonstrators streamed north until we found a blessedly unguarded bridge and cross over onto Michigan Ave, where the gas was still thick but at least it was possible to run.28

Night fell and tear gas still hung in the air. Tensions swelled outside the Hilton. Television cameras were everywhere, capturing scenes of excessive violence. There were beatings with fists, gun butts, and nightsticks. Mace was sprayed directly into people’s faces while police pushed them against walls and contained them tightly in cordons. At one point, protesters were pushed so hard against the outside of the Hilton that they went through a plate-glass wall, leaving shards of shattered glass buried deep in people’s skin. Upstairs, the fifteenth floor of the hotel turned into a temporary makeshift hospital as people tore bedsheets into bandages and rinsed out burning eyes. A reported four hundred people were treated for injuries from Mace and tear gas.29

The official record of the violent events that unfolded in Chicago is referred to as the Walker Report, produced by Daniel Walker, director of the Chicago Crime Commission (in a bid that later helped him become governor of Illinois). The Walker Report produced 20,000 pages of statements drawn from 3,437 interviews, 180 hours of film, and more than 12,000 photographs. The report called the violence at the convention a “police riot”:

Demonstrators attacked too. And they posed difficult problems for police as they persisted in marching through the streets, blocking traffic and intersections. But it was the police who forced them out of the park and into the neighborhood. And on the part of the police there was enough wild club swinging, enough cries of hatred, enough gratuitous beating to make the conclusion inescapable that individual policemen, and lots of them, committed violent acts far in excess of the requisite force for crowd dispersal or arrest.30

In distributing blame to the escalated tensions and to stressed-out individual police officers working too-long shifts in the sweltering heat, the Walker Report detracts attention from those authorities—like Mayor Daley and the Democratic Party—who sanctioned the use of force to control the protesters. Likewise, it obscures the coordinated, collective actions of riot police, who were drawing from the military and National Guard tactics spreading across US police forces throughout the 1960s. Journalist John Schultz argues, “What happened in Chicago during the last week of August 1968 was not a police riot. The result was chaos, but the cause was a premeditated disposition to subdue protest by whatever means necessary— a planned offensive.”31

Part of this deliberate and planned offensive involved the mass use of tear gas as a dispersal mechanism. In addition, tear gas served as a force multiplier and a punitive measure. The Mace sprayed in the face of protesters trapped in a small area outside the Hilton hotel was done not to de-escalate or disarm them but to punish them. At the same time, military-issued tear gas was intentionally deployed as a means to take over the city. From the military-issued sanitation truck to the adapted flamethrowers used to volley tear gas into crowds, new tactics and equipment were brought in to release tear gas in greater strength and quantities. So much was used that it entered cars, office buildings, homes, and even hotel rooms. It became an environmental weapon, a method of policing not only people but the atmosphere itself.32 This upgraded, offensive approach to tear gas deployment has since become standard in riot-control policing.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]