Žižek, the Matrix and 9/11

For Žižek, the metaphor of the Matrix represents how neoliberal capitalism colonises culture and subjectivity.

In response to 9/11, the philosopher Slavoj Žižek wrote Welcome to the Desert of the Real. In it, he argued that global capitalism and fundamentalism are two parts of the same whole, and that paradigms such as Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’ and Huntington’s ‘clash of civilisations’ restrict the range of apparent conflicts to cultural, ethnic and religious ones, masking anything more fundamental, such as economic conflict. His suggestion was that 9/11 and its aftermath had obscured reality rather than bringing us back to it. Global capitalism was itself a variety of fundamentalism, and America was complicit in the rise of Muslim fundamentalism, argued Žižek. Neoliberalism emerged more strongly after 9/11, since it harnessed the war on terror to suppress dissent, and used the tragedy to legitimise torture, rendition flights, and the horrors of Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo Bay.

To make sense of his argument, Žižek applied Baudrillard’s ideas to the World Trade Center attacks via the 1999 science-fiction film The Matrix. In The Republic, Plato imagined ordinary humans as prisoners tied firmly to their seats and compelled to watch the shadowy performance of what they falsely suppose to be reality on the walls of the cave. When some individuals escape the cave, they find that their ‘reality’ has merely been a shadow of the true reality. And that true reality is the Earth illuminated by the rays of the Sun, the supreme Good. In The Matrix, by contrast, those who awaken from the virtual reality generated by the eponymous mega-computer find the true reality to be nightmarish. The enlightened realise that each of us is effectively just a foetus-like organism immersed in amniotic fluid. Each of us is hooked up to cables that drain us of our life energy to power the Matrix itself.

For Žižek, the metaphor of the Matrix could be seen as representing how neoliberal capitalism colonises culture and subjectivity. For him, the Matrix is the Lacanian Big Other: ‘This utter passivity is the foreclosed fantasy that sustains our conscious experience as active, self-positing subjects – it is the ultimate perverse fantasy: the notion that, in our innermost being, we are instruments of the Other’s (Matrix’s) jouissance.’ The very reality we live in, the atemporal utopia staged by the Matrix, is produced so that we can be effectively reduced to the passive state of living batteries providing it with energy.

When the hero, played by Keanu Reeves, awakens into ‘real reality’, he finds himself in the burned-out ruins of Chicago after a global war. ‘Was it not something of a similar order that took place in New York on September 11? Its citizens were introduced to “the desert of the real” – for us, corrupted by Hollywood, the landscape and the shots of the collapsing towers could not but be reminiscent of the most breathtaking scenes in big catastrophe productions.’ The simulation preceded the real. The towers being hit by planes and then tumbling into rubble were not so amazing because we couldn’t believe it was happening, but because we’d seen it before in movies.

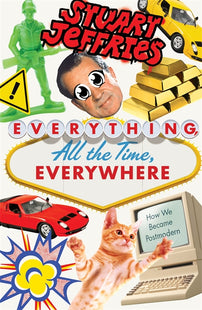

- the above is a short excerpt taken from Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern by Stuart Jeffries, a radical new history of a dangerous idea. You can read more in Slavoj Žižek's Welcome to the Desert of the Real.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]Postmodernism stood for everything modernism rejected: fun, exuberance, irresponsibility. But beneath its glitzy surface, postmodernism had a dirty secret: it was the fig leaf for a rapacious new kind of capitalism. It was the forcing ground of “post truth,” by means of which western values were turned upside down. But where do these ideas come from and how have they impacted on the world?

In this brilliant history of a dangerous idea, Stuart Jeffries tells a narrative that starts in the early 1970s and still dominates our lives today. He tells this history through a riotous gallery that includes, among others: David Bowie, the iPod, Madonna, Jeff Koons’s the Nixon Shock, Judith Butler, Las Vegas, Margaret Thatcher, Grand Master Flash, I Love Dick, the RAND Corporation, the Sex Pistols, Princess Diana, Grand Theft Auto, Jean Baudrillard, Netflix, and 9/11.