François Maspero: the resistance fighter with an ink-loaded rifle

François Maspero was a French journalist and author who passed away earlier this year. Verso presents this translated tribute to the founder of Éditions Maspero, the publishing house which has served as an inspiration for radical left publishing since the fifties.

A pair of texts by Mohamad Yefsah and Aymeric Monville

François Maspero died on 13 April 2015 at the age of 83. Here we present madaniya.info’s effort to pay tribute to this extraordinary individual and his eminent contribution to the struggle for the liberation of the Third World.

Grandson of the Egyptologist Gaston Maspero and son of the Sinologist Henri Maspero (a professor at the Collège de France) François Maspero was born in Paris on 19 January 1932. His youth was marked by the War, with his parents deported and his brother fighting as a maquisard in the Resistance; in 1944 his father died at Buchenwald (liberated 70 years ago last month) while his older brother was killed by the Germans in France.

In 1955 – without ever having completed his degree – he set up Editions Maspero, publishing texts on such matters as the War in Algeria, the opposition to Stalinism, underdevelopment, and neo-colonialism. Authors like Frantz Fanon, Louis Althusser, John Berger, Jean-Pierre Vernant, Pierre Vidal-Naquet, Yves Lacoste, Yannis Ritsos, and Nazim Hikmet wrote for Maspero, who in 1970 also published Alexander Sutherland Neill’s bestseller Libres enfants de Summerhill [English original: Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child Rearing].

As the president of the Institut du monde arabe and former culture minister Jack Lang put it, ‘François Maspero is more than a publisher, and more than a writer. François Maspero is a legend who embodies the virtues of a profound, radical engagement’.

François Maspero: the resistance fighter with an ink-loaded rifle

Mohamad Yefsah [1]

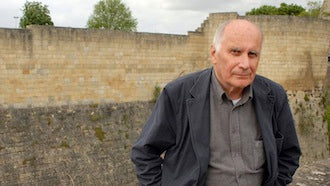

Who is this low-key old guy standing back from the crowd, with his faded grey jumper? An ex-boxer? Seeing the shy, furtive grinding of his teeth, or his sky-blue eyes darting around, you’d say that he was preparing for a fight. But at his age? His forehead creases, then he relaxes again… It’s François Maspero, a fighter of another kind: yesterday a publisher, today a writer, committed as ever, and present in Lyons for the inauguration of an exhibition devoted to his life.

Homage to a man of commitment

‘François Maspero et les paysages humains’: it’s one and the same title for two objects, an exhibition and a book that retrace the multiple journeys and struggles of this man, not only as a bookseller and editor but later as a translator, essayist and writer. He was paid this tribute on the fifty-year anniversary of his publishing house’s first book, Pietro Nenni’s La Guerre d’Espagne. And it’s quite a programme!

This rich volume comprises some fifteen contributions, including those by the writer Patrick Chamoiseau, the film maker Abdenour Zahzah, the translator Frachita Gonzalez Batlle and the publisher Eric Hazan. It also features prefaces that Maspero himself wrote for various authors, extracts of poetry, a few interviews that he had previously given, his old catalogue, photos, and posters.

‘One of the contemporary writers and essayists who most lucidly carry the unfinished song of our hopes, bearing it like a wound’, Maspero has remained faithful to his hopes and dreams, in an era in which the majority of the elite has thrown itself into the mouth of the neoliberal wolf. On his way he still sows the seeds that he picked up long ago, while others crush their past under their heels and celebrate the triumph of the victors of the day.

Edwy Plenel has spoken of ‘Maspero’s loyalty: a presence for the world, and for others, in the form of an anxious, concerned warning, keen to avoid fresh catastrophes. And for this presence, the colonial question is the key test: understood in a broad sense, as a rejection of any civilisation’s claim to superiority and any oppression that is supposed to be emancipatory’. Plenel evokes two figures, Charles Péguy and Maspero, separated in time but linked by their craft, namely that of the committed bookseller-publisher; Péguy as the defender of Dreyfus and Maspero as the partisan of Algerian independence.

The bookseller-publisher’s battles

The young Maspero made his debut in the book world by opening the L’Escalier bookshop in Paris, before taking over La Joie de Lire in 1957. In 1959 he set up the publishing house that took his own name. An artisan bookmaker and a partisan of struggle: these are two inseparable definitions of a man committed to the combats fought by the voiceless: workers and peasants, women and minorities, the colonised peoples and progressives the whole world over.

So it was at the height of Algeria’s war of national liberation that the La Joie de Lire bookshop and Editions Maspero were born, becoming the site where the murmuring of discordant voices could break out into the open. He gave a platform to the colonised – and this was itself a blow against the dogged defenders of colonisation – as well as those in the heart of France itself who rejected the country’s war.

With the French State waging its war of pacification, and with parliament already having voted to hand full powers to Guy Mollet, Maspero unveiled the hidden face of the conflict, with its litany of torture, destruction and massacres perpetrated by the French army.

It ought to be understood that at the time the idea of ‘French Algeria’ was the dominant one, whether it was loudly proclaimed or only existed in people’s minds silently. There were hardly myriads of people in the opposite camp – yet the justice and humanity of their stance will go down in history. Maspero’s engagement in support of the emancipation of the Algerian people was no easy position to take, and it left him having to deal with threats and attacks.

La Joie de Lire was repeatedly bombed by the far Right, Maspero’s books were confiscated by the state even as they were being printed – and trials followed. But he was so obstinate and gutsy as a man that he was able to resist the pressure from the authorities and the threats from the determined partisans of colonisation. He then had to draw on whatever solidarity he could, remain vigilant, put up a guard, and deal with the material costs of the books that had been confiscated and the fines that had been handed down by the courts.

A resolute anti-colonialist, Maspero also directed his gaze elsewhere – far from Paris or from a France which perhaps thought itself the centre of the world – toward other continents trembling with the cries of the oppressed.

He opened his door to the struggles taking place far afield, from Cuba to Africa, passing via the experiences of the countries of the East (far from an ‘actually-existing socialism’), and on to the struggles of Blacks in America, women, minorities, and the various forms of resistance to the capitalist system – though without ever forgetting about France.

The exhibition, curated by Bruno Guichard, perfectly gives account of the diversity of Maspero’s commitment, as we see in the titles of its sections: ‘Algeria’, ‘Cuba si’, ‘Vietnam’, ‘Palestine’, ‘the American Blacks’ long march to equality’, ‘the post-’68 years’ and still others whose titles are no less evocative. As the historian Julien Hage reminds us, ‘From June 1959 to May 1982 the Maspero publishing house brought out around one thousand three hundred and fifty titles across close to thirty collections, as well as a dozen magazines’.

The publisher published numerous books that turned out to be of very great importance, such as Les damnés de la terre [The Wretched of the Earth] (with a preface by Jean-Paul Sartre), by Frantz Fanon, whose works inspired the current theories of post-colonialism in the humanities.

[1] Mohammed Yefsah, an Algerian journalist, and PhD in Arts and Letters. His fields of interest are history and geostrategy. A contributor to La Cause littéraire, the Euro-Mediterranean website Babelmed, as well as France’s Médiapart.

The two deaths of François Maspero

by Aymeric Monville, 14 April 2015

He knew that history is tragic; or, as Chris Marker aptly said of him, he knew that words have a meaning.

Maspero would forever remain the man who was allowed to live while the Gestapo crushed all of his family; through a sadistic irony, at twelve years of age he was left alone with a sun that would never again shine so bright. He was the hero in spite of himself, who would have liked an obscure life at the back of his little bookshop, and yet found himself having to defend it, weapon in hand, against the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète killers.

This middle-aged man who saw his house of cards of hopes collapsing, and even failed in committing suicide. This was not the bankruptcy of a César Birotteau, but the demise of a politics. Perhaps that of a certain gauchisme, though it was hardly lacking in panache.

And it was this man who had to build everything anew – again, in books, but this time by writing them. Literature is the great victory of the defeated. Great writers are failed politicians; the inverse is equally true.

In the recent film devoted to him - François Maspero, les chemins de la liberté – he was still mischievously repeating a few old mottos that bore the mark of a serene sense of despair: ‘From defeat to defeat, toward the ultimate victory!’ (Victor Serge) or ‘There is no road, the road is made by walking’ (Antonio Machado).

And then there’s the image that he adopted for his finest book, Les Abeilles et la Guêpe, remembering how Jean Paulhan evoked the Resistance: ‘You can squeeze a bee in your hand until it suffocates, but it won’t die without having stung you first. That’s not much, but if it didn’t sting you, then bees would have died out long ago’. The Right has no monopoly on kamikazes.

‘Publisher and writer’, the bourgeois papers insisted in their obituaries (whether or not they’d prepared them in advance). As if the second craft embellished or excused the first, which has an excessive whiff of lowly toil. And they hardly mentioned, if at all, that Maspero was also and firstly a bookseller, and that it was in this post that he displayed the most courage.

But enough of his many hats. All work is servitude, but every struggle is a beautiful one. And you should only be judged by your own peers. Comrades only judge each other in terms of their capacity to struggle, wherever they may be.

In the era of his first death – the demise of Maspero, the publisher – the Italian police orchestrated the fake suicide of his confrère Giangiacomo Feltrinelli. No one believed the story that Feltrinelli had thought it necessary to place a bomb on a train track and then succumbed to a mistake. Every book he published was already a bomb. Or else he wouldn’t have been doing his job properly.

- See our other posts on François Maspero here.

- Translated by David Broder; see the original French version here.