Teju Cole: Bad Laws

Israel's slow, cold violence, no less than the other kind, ought to be looked at and understood.

Not all violence is hot. There’s cold violence too, which takes its time and finally gets its way. Children going to school and coming home are exposed to it. Fathers and mothers listen to politicians on television calling for their extermination. Grandmothers have no expectation that even their aged bodies are safe: Any young man may lay a hand on them with no consequence. The police could arrive at night and drag the family out into the street. Putting a people into deep uncertainty about the fundamentals of life, over years and decades, is a form of cold violence. Through an accumulation of laws rather than by military means, a particular misery is intensified and entrenched. This slow violence, this cold violence, no less than the other kind, ought to be looked at and understood.

Near the slopes of Mount Scopus in East Jerusalem is the neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah. Most of the people who live here are Palestinian Arabs, and the area itself has an ancient history that features both Jews and Arabs.

The Palestinians of East Jerusalem are in a special legal category under modern Israeli law. Most of them are not Israeli citizens, nor are they classified the same way as people in Gaza or the West Bank. They are permanent residents. There are old Palestinian families here, but in a neighborhood like Sheikh Jarrah, many of the people are refugees who were settled here after the Catastrophe of 1948. They left their original homes behind, fleeing places like Haifa and Sarafand al-Amar, and they came to Sheikh Jarrah, which then became their home. Many of them were given houses constructed on a previously uninhabited parcel of land by the Jordanian government and by the UN Relief and Works Agency. East Jerusalem came under Israeli control in 1967, and since then, but with a greater tempo in recent years, these families are being rendered homeless a second or third time.

There are many things about Palestine that are not easily seen from a distance. The beauty of the land, for instance, is not at all obvious. Scripture and travelers’ reports describe a harsh terrain of stone and rocks, a place in which it is difficult to find water or shelter from the sun. Why would anyone want this land? But then you visit and you understand the attenuated intensity of what you see. You get the sense that there are no wasted gestures, that this is an economical landscape, and that there is great beauty in this economy. The sky is full of clouds that are like flecks of white paint. The olive trees, the leaves of which have silvered undersides, are like an apparition. And even the stones and rocks speak of history, of deep time, and of the consolation that comes with all old places. This is a land of tombs, mountains, and mysterious valleys. All this one can only really see at close range.

Another thing one sees, obscured by distance but vivid up close, is that the Israeli oppression of Palestinian people is not as crude as Western media can make it seem. It is in fact an extremely refined process, one that involves a dizzying assemblage of laws and bylaws, contracts, ancient documents, force, amendments, customs, religion, conventions, and sudden irrational moves, all of this mixed together and imposed with the greatest care.

The impression this insistence on legality confers, from the Israeli side, is of an infinitely patient due process that will eventually pacify the enemy and guarantee security. The reality, from the Palestinian side, is of a suffocating viciousness. The fate of Palestinian Arabs since the Catastrophe has been to be scattered and oppressed by different means: in the West Bank, in Gaza, inside the 1948 borders, in Jerusalem, in refugee camps abroad, in Jordan, in the distant diaspora. In all these places, Palestinians experience restrictions on their freedom and on their movement. To be Palestinian is to be hemmed in. Much of this is done by brute military force from the IDF—mass killing for which no later accounting is possible—or on an individual basis in the secret chambers of the Shin Bet; but a lot of it is done according to Israeli law, argued in and approved by Israeli courts, and technically legal, even when the laws in question are bad laws and in clear contravention of international standards and conventions.

The reality is that, as a Palestinian Arab, in order to defend yourself against the persecution you face, not only do you have to be an expert in Israeli law, you also have to be a Jewish Israeli and have the force of the Israeli state as your guarantor. You have to be what you are not, what it is not possible for you to be, in order not to be slowly strangled by the laws arrayed against you. In Israel, there is no pretense that the opposing parties in these cases are equal before the law; or, rather, such a pretense exists, but no one on either side takes it seriously. This has certainly been the reality for the Palestinian families living in Sheikh Jarrah whose homes, built mostly in 1956, inhabited by three or four generations of people, are being taken from them by legal means.

As in other neighborhoods in East Jerusalem—Har Homa, the Old City, Mount Scopus, Jaffa Gate—there is a policy at work in Sheikh Jarrah. This policy is twofold. The first is the systematic removal of Palestinian Arabs, either by banishing individuals on the basis of paperwork, or by taking over or destroying their homes by court order. Thousands of people have had their residency revoked on a variety of flimsy pretexts: time spent living abroad, time spent living elsewhere in Occupied Palestine, and so on. The permanent residency of a Palestinian in East Jerusalem is anything but permanent, and once it is revoked, is almost impossible to recover.

The second aspect of the policy is the systematic increase of the Jewish populations of these neighborhoods. This latter goal is driven both by national and municipal legislation (under the official rubric of “demographic balance”) and is sponsored in part by wealthy Zionist activists who, unlike their defenders in the Western world, are proud to embrace the word “Zionist.” However, it is not the wealthy Zionists who move into these homes or claim these lands: It is ideologically and religiously extreme Israeli Jews, some of whom are poor Jewish immigrants to the state of Israel. And when they move in—when they raise the Israeli flag over a house that, until yesterday, was someone else’s ancestral home, or when they begin new constructions on the rubble of other people’s homes—they act as anyone would who was above the law: callously, unfeelingly, unconcerned about the humiliation of their neighbors. This twofold policy, of pushing out Palestinian Arabs and filling the land with Israeli Jews, is recognized by all the parties involved. And for such a policy, the term “ethnic cleansing” is not too strong: It is in fact the only accurate description.

Each Palestinian family that is evicted in Sheikh Jarrah is evicted for different reasons. But the fundamental principle at work is usually similar: An activist Jewish organization makes a claim that the land on which the house was built was in Jewish hands before 1948. There is sometimes paperwork that supports this claim (there is a lot of citation of nineteenth-century Ottoman Land Law), and sometimes the paperwork is forged, but the court will hear and, through eccentric interpretations of these old laws, often agree to the claim. The violence this legality contains is precisely that no Israeli court will hear a corresponding claim from a Palestinian family. What Israeli law supports, de facto, is the right of return for Jews into East Jerusalem. What it cannot countenance is the right of return of Palestinians into the innumerable towns, villages, and neighborhoods all over Palestine, from which war, violence, and law have expelled them.

History moves at great speed, as does politics, and Zionists understand this. The pressure to continue the ethnic cleansing of East Jerusalem is already met with pressure from the other side to stop this clear violation of international norms. And so, Zionist lawyers and lawmakers move with corresponding speed, making new laws, pushing through new interpretations, all in order to ethnically cleanse the land of Palestinian presence. And though Palestinians make their own case, long and loud, and even though they persist in the face of despair—and though many young Jews, beginning to wake up to the crimes of their nation, have marched in support of the families evicted or under threat in Sheikh Jarrah—the law and its innovative interpretations evolve at a speed that makes self-defense all but impossible.

This cannot go on. The example of Sheikh Jarrah, the cold violence of it, is echoed all over Palestine. Side by side with this cold violence is, of course, the hot violence that dominates the news: Israel’s periodic wars on Gaza, its blockades on places like Nablus, the random unanswerable acts of murder in places like Hebron. In no sane future of humanity should the deaths of hundreds of children continue to be accounted collateral damage, as Israel did in the summer of 2014.

In the world's assessment of the situation in Palestine, in coming to understand why the Palestinian situation is urgent, the viciousness of law must be taken as seriously as the cruelties of war. As in other instances in which world opinion forced a large-scale systematic oppression to come to an end, we must begin by calling things by their proper names. Israel uses an extremely complex legal and bureaucratic apparatus to dispossess Palestinians of their land, hoping perhaps to forestall accusations of a brutal land grab. No one is fooled by this. Nor is anyone fooled by the accusation, common to many of Israel's defenders, that any criticism of Israeli policies amounts to anti-Semitism. The historical suffering of Jewish people is real—it is in fact one of the most uncontroversially horrific instances of persecution in human experience—but it does not in any way justify the present oppression of Palestinians by Israeli Jews.

A neighborhood like Sheikh Jarrah is an X-ray of Israel at the present moment: a limited view showing a single set of features, but significant to the entire body politic. The case that is being made, and that must continue to be made to all people of conscience, is that Israel's occupation of Palestine is criminal. This case should also include the argument that the proliferation of bad laws by the legislature and courts of Israel is itself against the interests of Jewish people, to the extent that it fuels the ancient and wrongheaded calumnies against them. Nothing can justify either anti-Semitism or the racist persecution of Arabs, and the current use of the law in Israel is a part of the grave ongoing offense to the human dignity of both Palestinians and Jews.

***

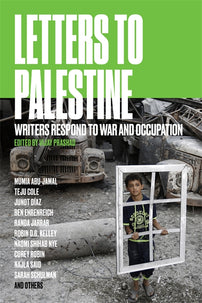

This is an extract from the essay ‘Bad Laws’, published in Known and Strange Things: Essays by Teju Cole. A version of this essay appears in Letters to Palestine, ed. Vijay Prashad.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]