Affective Mapping: An Excerpt from Atlas of Emotion

In this edited excerpt from Atlas of Emotion, Giuliana Bruno presents the feminist function of emotional cartography, and the tender "site-seeing" of cinema, including Marguerire Duras's Hiroshima mon Amour.

The Carte de Tendre

Designed by Madeleine de Scudéry (1607 – 1701) and first engraved by François Chauveau (1613 – 1676), the Carte de Tendre is part of the fictional making of lived space. In the course of Scudéry’s novel Clélie, the map–a narrative plan–is said to be the design of the eponymous character, who draws it to show the way to the land of Tendre.

Scudéry produced a spatial mapping of emotions, inscribing affects into an architectonics that was a social map. In this respect, the power of her vision can be inspirational today, not just for the political assertion of desire in its discourse, but because it allows us to remap a politics of affects, by putting affects back on our map, and thus to change our own navigational charts. In a way, I see Scudéry’s map as an early symptom of what Julia Kristeva defines, in psychoanalytic terms, as “the intimate revolt.” This is a cartographic rendering of intimate experience, a domain that has been explored in psychoanalysis and extends over a much larger terrain. By showing how this tender map works and assuming tender cartography as a methodological vehicle, my intent is to reclaim this intimacy as a place of interpretation and, in the process, to place cinema on the map of the emotional road atlas. A return to emotion is politically essential for cultural movement, for, in feminist terms, politics closely affects the fabric of our intimate space. To my mind, this intimate experience positively includes the world of imaging and the cinematic “vessel” that carries these images across the social landscape.

Taking the image of the map as a means of such “transport,” the tender map can become, first of all, a guide to relational politics, stretching interpretive borders that were already stretched in our effort to reposition emotion on the cultural scene. In fact, as we are about to see, the most striking feature of the Carte de Tendre is the fluidity of its “tender” geography. This is an inhabited space that lacks borders; as such; it offers an affective journey that is uniquely suited to be carried across new frontiers of site-seeing, in a reversible cartographic exchange between its plan and our own geopsychic design.

A Mapping of Filmic Emotions

The “mapping impulse,” as the art historian Svetlana Alpers shows, has been a major force in the history of the visual arts, shaping, in particular, Dutch art in the seventeenth century, where picturing and mapping coincided and expressed a common notion of knowledge. As we have seen, the historical link between art and cartography—where mapping itself took place—now has been revived in a different form, marking our postcolonial age of diasporas. In its contemporary incarnation, the art of mapping is rerouted to picture a geography of transits. It is interesting to note that, rather than constituting itself solely as a descriptive art, mapping, in general, appears to be fleshing out its narrative impulse and new psychogeographic paths. An impulse, after all, is a force that both impels and is impelled by waves of feeling and states of mind.

Along this particular route of mapping we have encountered the observational space of the moving image and its way of charting emotion pictures. As we have seen, a form of mapping, tender to gender, has shaped the genealogy of filmic site-seeing on the emotional terrain that ranged from the peripatetics of the (memory) garden to the relational strolling of sentimental mapping. An architectural mobilization of affect and memory has taken place along this haptic way. The (dis)placement of affect onto space has given way to a passage, as the exterior world of the landscape has become protofilmically transformed into an interior landscape. This tender site-seeing not only configures the mode of protofilmic representation but pervades the subject of cinematic representation. Let us, then, turn to a consideration of the textual narrative of the tender geography as it presents itself in filmic narrative. As a map of emotions, Scudéry’s Carte de Tendre has made direct filmic appearances, and, in many indirect ways, has shaped an intertextual language of emotion in film.

The Carte de Tendre appears as a textual reference, for example, in the opening sequence of Louis Malle’s Les Amants (Lovers, 1958), framing the opening scene of its narration. As such an aperture, the map creates an entrance to the film and shapes its narrative development. As T. Jefferson Kline suggests, “at the level alluded to by La carte de tendre, Malle’s film addresses the very possibility of feminine subjectivity and feminine discourse.” In so doing, the borderless map of tenderness serves as more than a simple introduction to the film. It functions as a diagram of the film’s own sexual politics and discourse of affects. But the Carte de Tendre “touches” film architectonics in ways that go even beyond direct reference, for it opens the way to a geography in which space is the place of emotional interplay. Cinema is bound to tender mapping on this terrain of intertextuality, which is itself a geography “moving” in history—as shown by the films included in this book, from the intimate plans of Antonioni and Akerman, treated earlier, to the voyages of Rossellini and Greenaway, which we have yet to traverse.

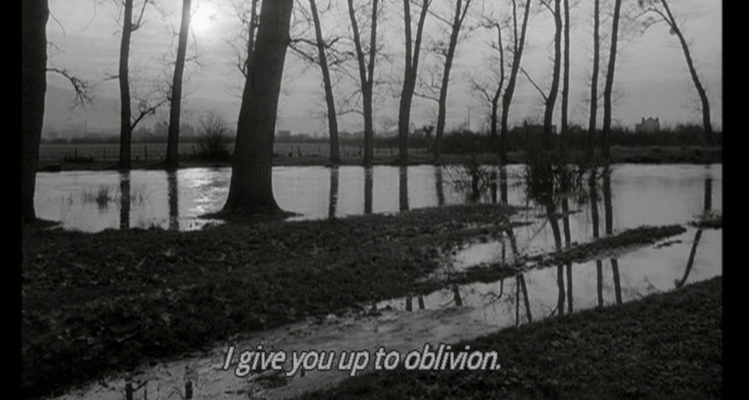

As a passage into this cartographic intertextuality, we pause momentarily to revisit Alain Resnais and Marguerite Duras’s Hiroshima mon amour and its cine-city travelogue, for it steps openly into Scudéry’s terrain. Although the map is neither referenced nor depicted in this film, Hiroshima mon amour can be read as an actual cinematic remake of the Carte de Tendre. Like Scudéry’s map, it designs intimate space as it enacts a narrative detour of emotional “transport.” Hiroshima mon amour creates a tender map in which a lover’s body stands for a city, while, conversely, the city itself is imagined as a corporeal affair. Let us recall that the city, as the female protagonist tells us, was made to the measure of love, just as her lover was made to the measure of her body. Here, taking us beyond mimesis to the edge of “mimicry,” a body map is lived and even explored as a site as, in turn, a city is tailored to a body—one’s own and that of loved ones. Her city fits (and “fashions”) a body of love. It is an intimate geography, a body-city on a tender map. As in Scudéry’s map, where exterior landscape reads as interior, emotions are architecturally rendered and spatialized along a course. Different topographies merge on this filmic map of love, incorporating one another. As in the Carte de Tendre, architecture becomes a body of experience, lived and loved. It becomes a metaphor—a means of transportation—for passionate traversals. Indeed, this mapping charts a journey: the way space designs intersubjectivity. Ultimately, one desires a site as one does a person. Bodies and cities involve the same seduction, give rise to the same tales of love. We absorb them with the same passion: one can literally fall in love with a place.

Atlas of Emotion by Giuliana Bruno is an award-winning cultural history of how we experience the world through art, film and architecture. It is currently 50% off as part of our Big Books sale (ends July 17!).

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]