Identifying ‘The Other’

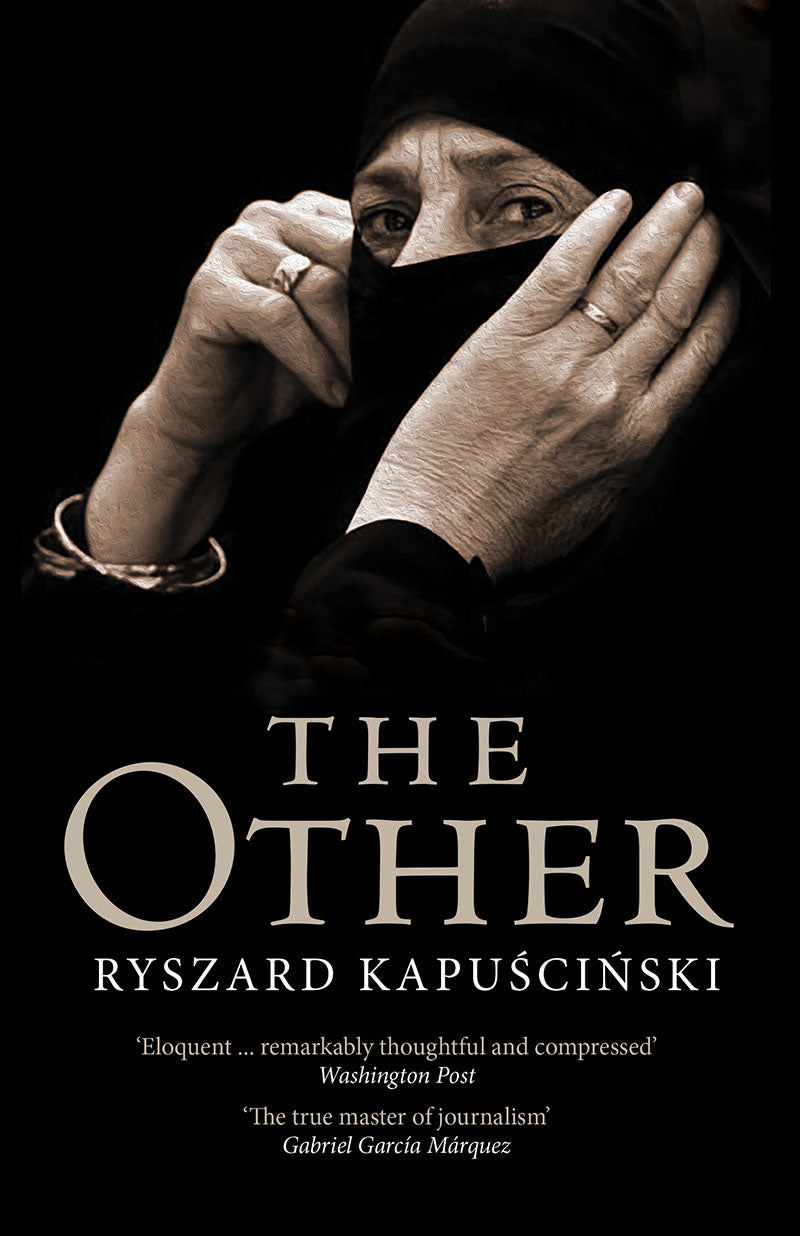

In this excerpt from Ryszard Kapuściński’s collected lectures on the concept of ‘The Other,’ the esteemed journalist grapples with the inextricable link between the Other and the Self.

Distilling a lifetime of learning and travel, Ryszard Kapuściński takes a fresh look at the Western idea of the Other: the non-European or non-American. Considering the concept through the lens of his own encounters in Africa, Asia and Latin America, and considering its formative significance for his own work, Kapuściński outlines the development of the West’s understanding of the Other from classical times through the Age of Enlightenment and the colonial era to the postmodern global village. He observes how we continue to treat the non-European as an alien and a threat, an object of study not yet sharing responsibility for the fate of the world. In our globalized but increasingly polarized age, Kapuscinski shows how the Other remains one of the most compelling ideas of our time. It is one of our core texts on our student reading lists and 50% off for the month of September as part of our Back to University sale. See all of our Anthropology reading here.

My Other

The theme of the 'Stranger' or 'Other' has obsessed and fascinated me for a very long time. In 1956 I made my first long journey outside Europe (to India, Pakistan and Afghanistan), and from that moment to the present day I have been concerned with Third World issues, and thus with Asia, Africa and Latin America (though the term 'Third World' could also cover a considerable part of Europe and Oceania). I have spent most of my professional life in these parts, travelling and writing about the local people and their affairs.

I mention all this because here I would like to sketch – of necessity briefly – not a portrait of the Other in general, in abstraction, but a picture of my Other, the one I have met in native Indian villages in Bolivia, among nomads in the Sahara, or in the crowds bewailing the death of Khomeini on the streets of Teheran.

What is his world outlook, his view of the world, his view of Others - his view of me, for example? After all, not only is he an Other for me, I am an Other for him too.

The first thing one notices is my Other's sensitivity to colour, skin colour. Colour takes top place on the scale according to which he will divide and judge people. You can live your whole life without thinking, without wondering about the fact that you are black, yellow or white, until you cross the border of your own racial zone. At once there is tension, at once we feel like Others surrounded by other Others. How often in Uganda I was touched by children who went on looking at their fingers for a long time after to see if they had gone white! The same mechanism, or reflex even, of identifying and judging according to skin colour also used to work inside me. In the Cold War years, when there was an inexorable ideological division in force between East and West, demanding of people on both sides of the Iron Curtain a mutual dislike, or even hatred – as a correspondent from an Eastern bloc country somewhere out in the jungle of Zaire, I would happily throw myself into the embrace of someone from the West, and thus my 'class enemy', an 'imperialist', because that 'devious exploiter' and 'war-monger' was simply and above all white. Must I add how greatly ashamed I was of this weakness, but that at the same time I did not know how to resist it?

The second component of my Other's world outlook will be nationalism. As the American professor Iohn Lukacs so aptly observed not long ago, at the close of the twentieth century nationalism proved to be the strongest of all the 'isms' known to contemporary man. Sometimes this nationalism has a paradoxical nature, for instance when it appears in those African countries where there are not yet any nations. There are no nations, but there is nationalism (or, as some sociologists maintain, sub- nationalism). The nationalist treats his nation, and in the case of Africa, his state, as the highest value, and all others as something inferior (and often deserving con- tempt). Nationalism, like racism, is a tool for identifying and classifying that is used by my Other at any opportunity. It is a crude, primitive tool that oversimplifies and trivialises one's image of the Other, because for the nationalist the person of the Other has just one single feature - national affiliation. It does not matter if some- one is young or old, clever or stupid, good or bad - the only thing that counts is whether he or she is Armenian or Turkish, British or Irish, Moroccan or Algerian. When I live in that world of inflamed nationalisms, I have no name, no profession and no age - I am purely and simply a Pole. In Mexico my neighbours call me 'El Polaco', and the air hostess in Yakutsk summons me to board the plane by shouting 'Polsha!' Among small, scattered nations, such as the Armenians, there is a phenomenal capacity to see the map of the world as a network of points inhabited by concentrations of one's own compatriots, be it one single family or one single person. The dangerous feature of nationalism is that an inseparable part of it is hatred for an Other. The degree of this hatred varies, but its presence is inevitable.

The third component of my Other's world outlook is religion. Religious belief will feature here on two levels, so to speak - on the level of an ill-defined, non-verbalised faith in the existence and presence of transcendence, a Driving Force, a Supreme Being, God (I am often asked, 'Mr. Kapuściński, do you believe in God?', and what I reply will have immense influence on everything that happens thereafter); and on the level of religion as an institution and as a social or even political force. I want to talk about the second instance. My Other is a creature who believes deeply in the existence of an extra-corporeal, extra-material world. Yet that has always been the case. What is characteristic of the present day, however, is the kind of religious renascence that is apparent in many countries. The most dynamically developing religion today is undoubtedly Islam. It is curious that everywhere - and this is regardless of the kind of religion - where a revival of religious fervour occurs, the revival has a reactionary, conservative, fundamental character.

So here is my Other. If fate brings him into contact with some Other – Other to him – he will find three features of that Other the most important: race, nationality and religion. I have been trying to find a common factor in these features, to discover what links them. It is that each one of them carries a huge emotional charge, so big that from time to time my Other is incapable of controlling it, and then it comes to conflict, to a clash, to slaughter, to war. My Other is a very emotional person. That is why the world he lives in is a powder keg rolling dangerously towards the fire.

My Other is a non-white person. How many of them are there? Today, 80 per cent of the world is non-white.

Occupied with the fight between East and West, between democracy and totalitarianism, not all of us were aware, and not all at once, that the map of the world had changed. In the first half of the twentieth century this map was arranged on the principles of a pyramid. At the top were historical subjects: the great colonial powers, the white man's states. This arrangement broke down before our eyes and in our lifetime, as more than a hundred new - at least formally independent - states inhabited by three-quarters of humanity appeared on the historical arena almost over- night. And so here is the new map of the world, colourful, multicoloured, very rich and complex. Let us note that if we compare the map of our world from the 1930s with the map from the 1980s, we get two completely different images of it. But in fact, the relationship between these two images is never static - it is undergoing constant change, constant dynamic and unstoppable evolution. In the latest history, the history that is happening right now, our Third World Others are gaining ever greater and ever more meaningful subjectivity. That is the first thing, and secondly, there is an invasion happening (a demographic one, to earn money, but it is an invasion) of representatives of the Third World into developed countries. It is estimated that by the mid-twenty- first century people from Asia and Latin America will constitute more than half the population of the United States.

More and more emigrants from Ireland and Norway, and more and more from Ecuador and Thailand, will move about the world with American passports in their pockets.

How prepared are we, the citizens of Europe, for this change? Not very, I'm afraid to say. We treat the Other above all as a stranger (yet the Other does not have to mean a stranger), as the representative of a separate species, but the most crucial point is that we treat him as a threat.

Does modern literature help to break down these prejudices, our ignorance or our plain indifference? Once again, I don't think it does much. I looked through the French literary awards for the past year, and did not find a single book with something to say about the widely understood modern world. There were love triangles, father-daughter conflict, a young couple's failed life together – things that are certainly important and interesting. But I was struck by the disdainful attitude towards the whole new trend in literature, just as fascinating, whose representatives are trying to show us the modern cultures, ideas and behaviour of people who live in different geographical latitudes and who believe in different gods from us, but who do actually constitute part of the great human family to which we all belong. I am thinking for example of The Innocent Anthropologist by Nigel Barley, of Colin Thubron's superbly written book Behind the Wall or Bruce Chatwin's excellent Songlines. These books do not win prizes, they are not even noticed, because – in some people's opinions – they are not so-called real literature.

On the other hand so-called real literature isolates itself from the problems and conflicts experienced by billions of our Fremde. For example, one of the greatest dramas of the modern world, a drama particularly acute for America, was the Iranian revolution, the overthrow of the Shah, the fate of the hostages and so on. To my amazement, in the course of the dozen or more months when these events were happening I did not meet a single American writer in Iran, nor in fact a single writer from Europe. How can it be possible, I wondered in Teheran, for such a great historical shock, such an unusual clash of civilisations, not to stir any interest among the world's writers? Of course it is not that they should immediately rush off en masse to the latest trouble spot, to the Persian Gulf - but the fact that literature can completely ignore a world drama being played out before our very eyes, leaving it entirely up to the television cameras and sound operators to tell the story of major incidents, is to me a symptom of a deep crisis on the front line between history and literature, a symptom of literature's helplessness in the face of modern world events.

So, despite an entirely new map of the world, researching, fathoming, interpreting and describing the philosophies and existence, the thinking and way of life of three-quarters of the world's population still remains – as in the nineteenth century – in the hands of a narrow group of specialists: anthropologists, ethnographers, travellers and journalists.

The Stranger, the Other in his Third World incarnation (and so the most numerous individual on our planet), is still treated as the object of research, but has not yet become our partner, jointly responsible for the fate of the planet on which we live.

For me the world has always been a great Tower of Babel. However, it is a tower in which God has mixed not just the languages but also the cultures and customs, passions and interests, and whose inhabitant He has made into an ambivalent creature combining the Self and non-Self, himself and the Other, his own and the alien.