On the Paris Commune: Part 3

The third installment of a new text by Stathis Kouvelakis on the development, events and legacy of the Paris Commune, published in three parts across the week.

Politics beyond the State

Already in Marx and Engels's lifetime, the most controversial problem raised by the Commune and their analyses of it was the question of the state; or, in other words, the question of the Commune's real nature as a form of political power. This experience seemed to defy all existing classifications — hence why Marx and others after him termed it a 'sphinx'. Indeed, this debate is anything but straightforward. In the first draft of his The Civil War in France, Marx had spoken of the Commune as 'a revolution against the State itself' [1]— not against a particular political regime. But he did not use this formulation in the final version, instead limiting himself to a brief comment remarking that, under a generalised Commune-regime, state power would be 'superseded'. As for the anarchists, Bakunin saw the Paris events as a 'bold, clearly formulated negation of the State'[2]— though he also qualified this assessment later on in the text, as he bemoaned the grip of 'Jacobin' ideas on both the actors in the Commune and the wider Paris population. Kropotkin and a whole new generation of anarchists instead drew the conclusion that, while the Commune had upheld a new ideal, it was much too mired in the 'tradition of the state and representative government'. To this, they counterposed the idea of a communism based on a thoroughly decentralised vision of communal organisation.

In his State and Revolution — one of his most famous texts, long providing revolutionary Marxists with their basic framework for interpreting this question[3] — Lenin closely studied Marx and Engels's writings, and emphasised the Commune's supposed moves to 'smash the state'. For the Bolshevik leader, the Commune represented a 'democracy' which transformed into 'something which is no longer the state proper', for here 'the majority itself can directly fulfil all these functions' which had previously been 'the special institutions of a privileged minority'.[4] He emphatically restated Engels's formulations on communism as the 'withering-away of the state' — itself synonymous with the 'withering-away of democracy', insofar as Lenin (contrary to Engels’s suggestions in The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State[5]) considered that 'democracy' necessarily meant a state form.[6] Nonetheless, he added, getting this far would require a 'strict, iron discipline backed up by the state power' and an organisation of political life in which there 'is no departure whatever from centralism' — an idea which he curiously attributed to Marx's discussion of the Commune.[7] Yet, in the conclusion of this text, Lenin then reversed these earlier formulations, stating that 'the Commune was able in the space of a few weeks to start building a new, proletarian state machine'.[8] We should also add that, for Lenin, this new machine — which certainly was meant to be transitional and anti-bureaucratic — also had to rely on an organisation of the economy in which 'All citizens are transformed into hired employees of the state, which consists of the armed workers. All citizens become employees and workers of a single countrywide state “syndicate”'.[9] It then becomes easier to understand the — to say the least — contradictory legacy of this text. It has been read as a quasi-libertarian manifesto, the work of a Lenin who on the eve of the October Revolution dreamt of a soviet power that would make it possible rapidly to get rid of the state. But so, too, as an underhandedly statist line of argument, through which the proclamation of a libertarian objective ('Under socialism all will govern in turn and will soon become accustomed to no one governing')[10] serves to excuse repressive measures, paving the way for an authoritarian regime. These measures were, admittedly, meant to be temporary — but as history has shown, nothing risks turning out more permanent than the temporary. The problem takes on further levels of complexity if we consider the stance of such convinced 'anti-authoritarians' as the leading Communards Arthur Arnould and Gustave Lefrançais — who have the advantage, over other revolutionaries, that they took part in a real revolution. Drawing the lessons of the Commune, they made the case for a 'dictatorship' over military matters (precisely what the Commune failed to do) and even spoke of a centralisation of public services in the future liberated society, embracing the essential social functions (communications, defence, diplomacy, public services) which would still need to be handled on a national scale.[11] The communism that Lefrançais envisages in his memoirs does not even seem to involve the abolition of the state: as he puts it, 'in future the state would be nothing but the simple expression of the communal interests organised on the basis of solidarity'.[12] Such discussions of the problem suggest that the relationship between means and ends cannot be resolved via a few simple formulae, abstracted from political practice.

To try and untangle this problem, we will pick up just one of its threads, namely Marx's reflection on the state and revolution. Indeed, this theme runs throughout his writings on France, the main hotbed of the revolutions of the nineteenth century. As he told Kugelmann,[13] the experience of the Commune compelled him to revisit and rework the fundamental conclusion he had reached two decades earlier in the Eighteenth Brumaire. Through the abrupt twists and turns that marked the conjuncture running from February 1848 to the Bonapartist coup d'état, Marx had seen another, much deeper and more 'organic' tendency at work: the history of the formation of the modern state. This process had begun with the absolutist monarchy's efforts to centralise the state; it had then continued with the French Revolution and was completed under Napoleon. But the modern state had further developed under the regimes that followed, including the republican one that emerged from the February 1848 revolution.[14] Thus, behind the varied succession of political regimes, there was a more powerful tendency at work: namely, the construction of an ever denser and more ramified state machine (Staatsmaschinerie), which created a bureaucracy 'whose work is divided and centralized as in a factory'.[15] This machine dispossessed society of its 'common' interests, transforming them into 'an object of government activity'.[16] The 'common' thus became a hypostasised 'general interest' embodied in the state, which moulded and gained mastery over this interest by it by 'snatch[ing]' control over the 'activities' coming from below. This proved much more deep-rooted a process than the multicoloured array of political regimes that came and went according to the vagaries of the conjuncture. Yet, Marx now claimed, if 'all revolutions' of the past had 'perfected this machine instead of breaking it', the revolution of the future — and the 'centralization of the state' it would enact — demanded the demolition of the state machine' [die Zertrümmerung der Staatsmaschinerie].[17] This was a specific aspect of the proletarian revolution which made it impossible to consider it on the model of the bourgeois revolution'. The revolution that would 'raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class', as the Manifesto put it, could not anymore be considered analogous to the rise of the bourgeoisie; it demanded a much deeper rupture with the organisational forms of political power than had hitherto been imagined.

Yet, while Marx did here resume his reflection on the break of the state machine', he had already begun to revise his vision of revolutionary power on one essential point. In the 1869 edition of the Eighteenth Brumaire he struck out a passage from the original text which had said that 'the demolition of the state apparatus will not endanger centralization'.[18] The experience of almost two decades of intensified Bonapartist centralism — combined with the spread of ideas in favour of centralisation across the spectrum of French republican and socialist forces — led Marx to step away from the pro-centralisation positions that he and Engels had held during the revolutions of 1848. The Communist Manifesto had proclaimed that 'The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class'.[19] The concrete measures spelled out in the ten-point programme that followed listed the sectors that were intended to become part of a state-centralised organisation of the economy (centralised credit and means of transportation, an increased number of 'national factories', and the creation 'industrial armies, especially for agriculture').[20] Over the final phase of the revolutionary period that began in 1848, the German communists' immediate objective continued to be the creation of a republican regime; Marx and Engels insisted on the need for its strict centralisation: 'in opposition to this plan [for a federal republic] the workers must not only strive for one and indivisible German republic, but also, within this republic, for the most decisive centralization of power in the hands of the state authority. They should not let themselves be led astray by empty democratic talk about the freedom of the municipalities, self-government, etc.'[21] They emphasised that 'revolutionary activity ... can only be developed with full efficiency from a central point' and forcefully lay claim to (what they understood to be) the Jacobin model, insisting that '[a]s in France in 1793, it is the task of the genuinely revolutionary party in Germany to carry through the strictest centralization.'[22]

The Civil War in France revisited and further sharpened this thesis regarding the need for a rupture from the existing state machinery, a thesis which would, in turn, be incorporated into the 1872 preface to the Manifesto.[23] The only such foreword jointly signed by both Marx and Engels, it was written for a new edition which marked the real beginning of the wide circulation of this text. The preface said that if it were to be written again, the ten-point programme would 'in many respects, be very differently worded today'. Marx and Engels referred to two factors which made this part of the text 'antiquated': on the one hand, ' the gigantic strides of Modern Industry since 1848' and, no less importantly, the 'extended organization of the working class', an advance which resulted from the practical experience' of the February 1848 revolution and ' then, still more, in the Paris Commune'. This latter had 'proved one thing especially' — and the Preface cited The Civil War in France on this point — namely, that 'the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes'.[24] This revision thus immediately aimed at a rupture with the 'state machinery' by the revolutionary government which was meant to replace it. But it is also worth noting that there was no reference to the 'smashing' or the 'destruction' of the state in this text, in which Marx and Engels could express themselves free of the restrictions which applied when they wrote collective texts issued in the name of the International. In his — private — letter to Kugelmann, Marx added that 'what our heroic Party comrades in Paris are attempting' was to 'smash' [zerbrechen: to break] 'the bureaucratic-military machine', and that this should be considered 'essential for every real people's revolution on the Continent'.[25]

Let us take a closer look at what the Commune's 'practical experience' was in that respect, as analysed by Marx in The Civil War in France and especially its third, more theoretical part, devoted to discussing the 'character of the Commune'. The start of this section built on the line of argument formulated in The Eighteenth Brumaire, which was summarised in the corresponding part of the first draft. Here, Marx sought to shed light on the historical process that had formed the French bourgeois state, and unravel the mystery of its Bonapartist (Second Empire) form — i.e. a hypertrophied bureaucratic-repressive machinery which had grown autonomous from the bourgeoisie, 'apparently soaring high above society'. In fact, far from standing above the classes, this regime stripped the bourgeoisie of its direct political role while also ensuring an unprecedented development of both its economic power and its domination over labour: 'Imperialism [here in the sense of the Bonapartist regime] is, at the same time, the most prostitute and the ultimate form of the state power which nascent middle class society had commenced to elaborate as a means of its own emancipation from feudalism, and which full-grown bourgeois society had finally transformed into a means for the enslavement of labour by capital.'[26]

Nonetheless, there was a major difference between the first draft and the final version of The Civil War in France. The first draft had proceeded from what we might call the Tocquevillian narrative in the Eighteenth Brumaire, which retraced the emergence of a centralising state which developed under absolutism and whose edification was completed by the Revolution of 1789 and the regimes that followed. Here, 'The first French Revolution with its task to found national unity (to create a nation) ... was, therefore, forced to develop, what absolute monarchy had commenced, the centralization and organization of State power, and to expand the circumference and the attributes of the State power, the number of its tools, its independence, and its supernaturalist sway of real society'.[27] But, in the final version, the 'edifice of the modern state' — centralised and oppressive — was explicitly and exclusively attributed to the period of the 'First Empire', not that of the French Revolution, which was instead hailed as 'the gigantic broom that had swept away all the feudal relics which still served as obstacles to the emergence of the modern state'.[28] Directly echoing the discourse of the Communards, in which Marx had immersed himself throughout these weeks in April-May 1871, the Great Revolution was rehabilitated. Here, Marx cited two dimensions of the French Revolution which the Commune had breathed fresh life into: it was both a moment in which popular initiative was set loose by the demand for 'direct government', and it also meant the emergence of a revolutionary authority of a new type, opening the way to a rebuilding 'from below' of national unity and the internationalist horizon of the universal workers' republic. Before we press on with our reading of The Civil War in France, it is worth adding that in 1885 Engels mounted an explicit self-critique of the conceptions that he and Marx had associated with the French Revolution — and, by extension, the centralising positions they had defended in 1848 to 1850. In a note to the new edition of the March 1850 address to the Communist League, he emphasised that the claim that the 1793 government had 'carr[ied] through the strictest centralization' owed to a 'misunderstanding', which he blamed on 'the Bonapartist and liberal falsifiers of history'. The truth was that 'throughout the revolution up to the eighteenth Brumaire the whole administration of the départements, arrondissements and communes consisted of authorities elected by, the respective constituents themselves, and that these authorities acted with complete freedom within the general state laws'.[29] Engels continued by praising this 'self-government' (Selbstregierung, as he put it in a literal German translation), which Napoleon had hastened to abolish by replacing it with a centralised administration by prefects, ' a pure instrument of reaction from the beginning'.[30]

But let us get back to Marx's analysis of the Commune. The features of this political form, such as they transpire from this text, have been subjected to a number of commentaries. But whether they praise or criticise Marx, they seem to share in the assumption that he made the Commune the model — or rather, the ideal-type — to which any revolutionary authority must conform. Among his disciples, it was Lenin who first introduced this type of reading with his State and Revolution, thus contradicting his earlier positions in which the Commune had specifically served as a negative example of a revolutionary government.[31]

While they recognised its symbolic importance, it would seem that Second International Marxists refrained from taking Commune-form for a functional reference point guiding their vision of the socialist future (and this across all wings of the International, albeit in different ways: the right wing of the SPD was overtly hostile, the left rather more nuanced).[32] The anarchist/libertarian 'communalist' tradition also has its own particular use of the Commune as a reference point, for instance in the work of Murray Bookchin, to take just one recent example. Marx's critics have instead emphasised the fundamental inadequacy of such a model and/or the measure of romanticisation inherent in such an approach — in other words, the gap separating the dream of the Commune from the Commune 'such as it really was'. The term 'transfiguration' — as Jacques Rougerie termed Marx's interpretation of the Commune — is often used, here. But this is to forget that Rougerie himself specified that The Civil War in France, an ‘exposé of Marx's ideas', is a 'transfiguration (not a disfigurement)' of the Commune.[33] And that, on the 'crucial point' of the state and of the political form that would make superseding it an imaginable prospect — 'a project that still endures within the workers' movement', Rougerie wrote in a 1971 article — 'Marx sought to preserve its best aspect'.[34] Indeed, interpretations of Marx's text often pay all too little heed to its status and the unique method that he strove to deploy therein. So, we should remember that The Civil War in France was entirely written 'in the heat of the moment', mainly during the Bloody Week, and that it was a collective text — the Address that the International had some weeks earlier promised to communicate to its members. It is often forgotten that the greater part of this text was devoted to refuting the narrative of the Paris events spread by the international press of the time. In unison with all governments, this newspaper coverage reduced the Commune to an explosion of destructive energies and a succession of apocalyptic images, saturated in references to blazes, 'pétroleuses' and ruins — even if the 'excesses' of repression did discomfit some among the foreign correspondents in Paris.[35] The 'communist plot' attributed to IWMA and its 'chief in London' — Marx — occupied a central place in this narrative. These attacks had the paradoxical effect — if a rather commonplace one in Marx's case — of granting sudden celebrity to their target and contributing (among other factors) to the publishing success of The Civil War in France, such as none of his previous texts had enjoyed.[36]

This function of the text — combined with the fact that it was near-simultaneous to the event it described — itself explains some of the characteristics which it has most been criticised for. For instance, the gap between the almost uniformly laudatory portrait of the Commune in The Civil War in France, and the more realistic assessment we find in Marx's correspondence. To mention just a few examples that often recur in commentaries: in his published text, Marx went no further than point to the 'merely defensive attitude' that the Central Committee of the National Guard had taken in the days following 18 March, even as Versailles was rapidly reorganising its armed forces. He also praised the fact that, under the Commune's authority, 'the proletarian revolution remained ... free from the acts of violence in which the revolutions ... of the “better classes” abound'. Marx even went so far as to attribute the executions of generals Lecomte and Thomas to the 'inveterate habits acquired by the soldiery under the training of the enemies of the working class' — habits which they could hardly shake off overnight when they rallied to the other side.[37] But, in his letters, Marx issued a much harsher assessment of the Commune's military efforts, and judged that, despite the reassuring reports, Serraillier was sending from Paris, the battle was lost since early April. Even more tellingly, where The Civil War in France spoke of the Commune as a 'working, not a parliamentary body, executive and legislative at the same time', his 13 May 1871 letter to Frankel and Varlin instead pointed to the time that had been wasted on 'trivialities and personal quarrels'. These problems were well-known, and Marx's comments echoed debates that the actors in the Commune had themselves been having — for he took particular care to avoid any appearance of laying down lessons. Even his expertise on economic matters was only offered after the Parisian leaders had sought his insight. A text expressing a specifically IWMA point of view, The Civil War in France could thus still less take a stance on questions that had divided the Commune Council and even the International members among its ranks. This was not least true of the divide between a 'majority' and a 'minority' over the question of forming a Comité de salut public — later notes suggest that Marx took a position distant from both camps. Even more tellingly, in his additions to the German translation of Lissagaray's History of the Paris Commune, published in 1877 and subject to a full revision by Marx, he hinted at serious doubts as to the 'working-class' character of the 'Communal government' — an assessment foreshadowing the one that he provided in his 1881 letter to Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis in which he wrote 'the majority of the Commune was in no sense socialist, nor could it be'.[38] Doubtless, the antics of the Communard exile community in London and Marx's (and Engels's) own tangles with many of its members had a grave effect in driving this turn.[39] In his additions to the German translation of Lissagaray's text (which he entirely supervised), Marx also damned the Commune's reluctance to make its debates public. It is worth noting that Marx either kept these more critical judgements private or else smuggled them in under another writer's name (as in the case of this translation of Lissagaray's History). In their public texts, Marx and Engels adopted similar formulations to The Civil War in France. Hence in his 1891 introduction to this text, Engels wrote that 'As almost only workers, or recognised representatives of the workers, sat in the Commune, its decisions bore a decidedly proletarian character’.[40]

Moreover, we need to reckon with the fact that, despite the impressive array of sources Marx gathered and the information from Paris he could draw on (inevitably focusing on the urgent demands of the moment), many facets of the Commune escaped his notice. This is especially true of certain aspects that have attracted the attentions of contemporary historians seeking a view of the events 'from below'.[41] Writing in the immediate aftermath of this event, freeing the Communards of the image they had been granted in contemporary reports — painting them as barbaric arsonists — and establishing the facts on the carnage in the streets of Paris, doubtless seemed a more pressing task.

Should we conclude, then, that Marx and Engels took a deliberately duplicitous approach — combining a public discourse that provided an idealised image of the Commune with another, private one in which they expressed how they 'really' saw things? This would be a rather rash conclusion, overlooking the close relationship between these texts and the conjuncture of which they were part — and the function they were meant to play therein. Introducing The Civil War in France to a German audience in 1891, Engels could hardly have distanced himself from its content — for this would have meant disavowing Marx, whose authority was hardly unchallenged within Social Democracy. He was still less able to do so in a moment in which the SPD's right wing was hard at work in denigrating the Commune, as it sought to reject any notion of a revolutionary rupture in Germany. Yet, as we have seen, while Marx was very much conscious of the Commune's internal tensions and debates, when he analysed its socialisation projects he tried to capture the part of the event that had gone beyond them. This meant grasping the Commune's characteristic element of the unprecedented, in which Marx had seen emerging elements of communism— at least partly going beyond the initial intentions and the consciousness of actors who only 'discovered' this after the fact. In an 1884 letter to Bernstein, Engels summarised Marx's method as follows: 'That the Commune's unconscious tendencies should, in The Civil War, have been credited to it as more or less deliberate plans was justifiable and perhaps even necessary in the circumstances'.[42]Some commentators saw in what Engels says here a certain 'lack of caution' — revealing, in Georges Haupt's words, the problematic character of a 'theoretical model of the Commune based on interpretation and projection'.[43]Or even, as Robert Tombs puts it, a calculated bid to spread 'myths', by 'repeating contemporary propaganda as fact, assuming the actual application of measures that existed only on paper, [and] misinterpreting or exaggerating acts and intentions'.[44]Yet, however critical or polemical they may be, these commentaries also emphasise the necessarily 'interpretative' character of any analysis of the event — the real question being whether it corresponds to the 'projection' of the authors' desires alone, or if it draws on verifiable, tangible elements of the situation. In other words, whether the hypotheses this analysis formulates allow us to explain the processes underlying this event, and give a coherent overall picture which is also able to integrate new elements.

In his analysis of the Commune as a political form, Marx drew less on the Commune's real achievements — of whose limits, we have seen, he was well aware— than on its 'programme', as articulated by its most emblematic decisions, its proclamations, and in a certain sense its discourse itself. But unlike some, Marx did not consider this discourse a matter of merely rhetorical exercises 'exist[ing] only on paper'. For he was conscious of what one contemporary jurist well grasped, as she delved into the Commune's legislative efforts: 'If for historians, the Paris Commune marked a high point of class struggle and an opening for social progress, for jurists it could be one of the key moments in the construction of essential juridical notions. For in a revolution words are not only weapons but also "acts" [actes — also in the sense of legal and legislative documents]. The Commune's revolutionary work proceeded by way of discourse and action, discourse made into acts'.[45] If this is so, it refers not to any mysterious 'performative' properties the Commune supposedly had, but to the fact that this discourse was carried forth by the concrete activity of 'masses' in movement. It was their aspirations it translated — even through its uncertainties and limitations — along with the reality of their transformation into historical actors.

So, it was the Paris masses' aspiration to govern themselves — and, faced with an intransigent adversary, their willingness to commit to a process of social transformation — that allowed Marx to re-elaborate his ideas on the nature of revolutionary government. Two closely linked ideas immediately become central, here. On the one hand, the Commune both confirmed and itself embodied the idea of a rupture with the state machinery. It had not just sketched out but experimented with the first outlines of a different institutional configuration — an expansive form that itself spurred the fight for social emancipation. On the other hand, while this rupture process did emphatically lay claim to the republican tradition and continued on from tendencies that had already surfaced in previous revolutionary moments of, it could hardly be reduced to this alone. The Commune was not simply the 'true', 'Social' Republic of 1848, but also its transcendence in favour of something new. Indeed, it allowed this something new to be given a name — an adequate name, if perhaps also a temporary one.

Let us begin with this second aspect. In The Civil War in France, Marx had defined the Commune's relationship with the Republic as follows: 'The direct antithesis to the empire was the Commune. The cry of “social republic,” with which the February Revolution was ushered in by the Paris proletariat, did but express a vague aspiration after a republic that was not only to super[s]ede the monarchical form of class rule, but class rule itself. The Commune was the positive form of that republic.'[46] A passage in the first draft further explained this idea: 'The Republic had ceased to be a name for a thing of the past. It was impregnated with a new world. Its real tendency, veiled from the eye of the world through the deceptions, the lies and the vulgarizing of a pack of intriguing lawyers and word fencers, came again and again to the surface in the spasmodic movements of the Paris working classes (and the South of France) whose watchword was always the same, the Commune!'[47] Fully conscious of the Communards' ardent republicanism and the omnipresent references to 1789-93 and 1848 — and doubtless impressed by this — Marx identified elements of both continuity and rupture. There was continuity, with the sans-culotte demand for direct government, but also with the energy of the revolutionary assemblies. As we have seen, this led Marx to revise his views regarding the role of the Great Revolution in the emergence of the bourgeois state. There was a further continuity with the first expression of proletarian aspirations, as crystallised in the 1848-inspired call for a 'Social Republic'. But most importantly, there was a rupture. For this was not simply a matter of changing France's political regime, but of putting an end to class domination, including that domination perpetuated under a republican order. But such a task could not be fully conceived — and thus fully realised — with (and within) the old words. Between the Republic (even if given an added 'social' aspect) and the Commune, there was a great rift produced by the rupture with the old state machine, by way of the masses' direct action. And this rupture was the necessary condition if the Commune was to prepare the way for the abolition of class domination. In a sense Marx here provided a pre-emptive response to Jean Jaurès's 'synthesis' between socialism and republicanism, by revealing its true nature, as an attempt to integrate the workers' movement into a Republic whose fundamental structures were unchanged, on the grounds that the very concept of ‘Republic’ was supposedly open to the realisation of the 'socialist ideal'. For Jaurès, socialism was indeed essentially a matter of 'ideals' and the republican synthesis he professed marched his synthesis between the 'materialist' and 'idealist' conceptions of history such as he understood them, i.e. a synthesis between the effect of economic factors and the action of humans driven by their consciousness toward 'an intelligible direction and an ideal sense', thus realising their human essence.[48] For Marx, conversely, the Commune — 'the positive form of that republic', the 'Social' republic dreamed of in 1848 — was summoned to replace it. The Commune heralded the 'new world' with which the Republic had been pregnant; it still saw itself in connection with the republican form, with which it identified more than anything, but its own dynamic pointed further. The Commune, wrote Marx, 'supplied the republic with the basis of really democratic institutions. But neither cheap government nor the “true republic” was its ultimate aim; they were its mere concomitants.'[49] He continued — in the passage we have here discussed at some length — by unveiling its 'true secret', namely that it was 'essentially a working class government', 'the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economical emancipation of labour'.[50] But, as we have also seen, the Commune was 'not the social movement of the working class ... but the organized means of action'; and on this basis, we can also think that, being a mediation, it was itself nothing but a temporary name, destined itself to be superseded in the course of the long process that 'affords the rational medium in which that class struggle can run through its different phases in the most rational and humane way'.[51] In worldly history and politics, no name — however necessary in a given moment — should indeed be considered final.

'Smashing' and/or 'transforming' the state machine?

As a positive form of the 'social republic', the experience of the Commune made it possible to grasp concretely what happens to the pre-existing state machine during a social revolution of a new type. For this was a revolution that gave rise to a 'thoroughly expansive political form', making the emancipation of labour an effective possibility. At this point, we should start with a terminological clarification: the 12 April 1871 letter to Kugelmann spoke of the need to 'smash' (zerbrechen) the political-military machine and referred to his Eighteenth Brumaire, in which Marx had used the terms 'breaking' (brechen) and 'destruction/demolition' (Zertrümmerung). The first draft of the Civil War in France again employed this strongly anti-statist terminology: 'It was not a revolution to transfer it from one fraction of the ruling classes to the other, but a revolution to break down this horrid machinery of class domination itself';[52] the same verb (to break) also appeared three further times in Marx's preparatory manuscript. Yet, in the final version of The Civil War France — in a passage also incorporated into the 1871 preface to the Communist Manifesto —, Marx did not speak of 'breaking' the state as such, instead declaring that 'the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes'.[53] This formulation implied the need for a transformation of the state machine, rather than its destruction. He kept the term 'destruction', but now with reference to 'the destruction of the state power which claimed to be the embodiment of that unity independent of, and superior to, the nation itself, from which it was but a parasitic excres[c]ence.'[54] This would suggest that the Tocquevillian terms which Marx had used to characterise the state in his draft manuscript were closely bound up with his disgust at the Bonapartist ‘imperial’ regime. He defined the Commune as the '[t]he direct antithesis to the Empire' — not to the state per se, or even to the bourgeois republic. Moreover, to 'destroy' a 'state power' or destroy the 'state machine' is not the same thing as 'smashing the state': a 'state power' could break and collapse (like Napoleon I's First Empire, for instance) without its underlying material apparatus being destroyed. Indeed, this is the thrust of Marx's own exposition, which underscores the continuity of the state machine, notwithstanding the varied succession of regimes that had come and gone since.

So, how are we to interpret this shift in Marx's reasoning? Did it simply express a desire to soften the more personal, exploratory formulations he had advanced in his first draft, now that he was writing a text on behalf of the IWMA as a whole? Did it reflect a measure of uncertainty and/or ambivalence in his thinking? It is worth noting that the only subsequent text in which Marx revisited the question of the state as a theoretical problem — the Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875) — spoke only of 'transforming the state'. Largely devoted to refuting Lassallean statist socialism, this text called the 'transition period' between capitalist society and communism the 'dictatorship of the proletariat'. It defined this transformation as the radical reduction of the state's autonomy from society, i.e. as the process that 'convert[ed] the state from an organ superimposed upon society into one completely subordinate to it'.[55] 'The question then arises', Marx continues, of 'what social functions will remain in existence [in a communist society] that are analogous to present state functions?' This idea continues in line with formulations in The Civil War in France referring to the 'legitimate functions' of the 'old governmental power' which had 'to be wrested from an authority usurping pre-eminence over society itself, and restored to the responsible agents of society'.[56] In very similar terms, the first draft spoke of how the Commune had made 'the public functions — military, administrative, political — real workmen’s functions, instead of the hidden attributes of a trained caste)',[57] thus expressing the idea of a debureaucratisation process that would transform the state's functions. This debureaucratisation was not so much a total deprofessionalisation of these functions (even if it did mean simplifying and reducing them as far as possible) as of subjecting them to social control and the principle of public accountability. It was also clear that this transformation would entail a clear rupture with the state's repressive functions in particular; this really was a matter of 'breaking' the state machine, leading as it did to the dismantling of the repressive state apparatuses. So, here, the important thing is to understand the nature of a revolutionary government, its relationship with the state, and its relationship with the 'mass' political practices that accompany its emergence but seem doomed to perish once it has consolidated itself. To try to shed some light on this question — one on which a lot of ink has been spilt already, through many and varied interpretations — we need to delve more deeply into both Marx's text and the historical reality of the Commune. The portrait of the Commune in the third part of The Civil War in France points us in two main directions, in this regard, which we will each examine in turn: firstly, the historical development of the state machinery itself, and then, in the next section, the institutional project that the Commune designed and carried forth.

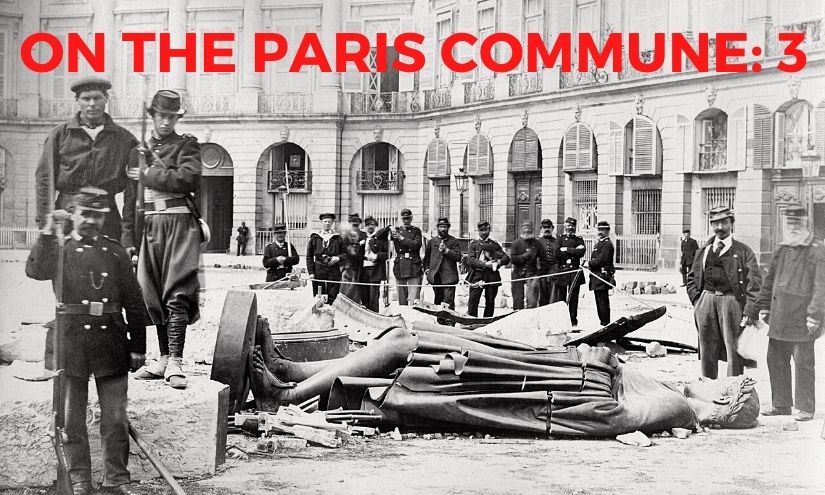

Let us begin with the measures that fulfilled the Commune's transformation of - or rupture - with the 'bureaucratic-military machine'. 'The first decree of the Commune', Marx notes, 'was the suppression of the standing army, and the substitution for it of the armed people.'[58] In issuing this 30 March 1871 decree, the Commune was confirming what was already a fait accompli, given the flight of the Versailles government following the 18 March insurrection, and the de facto seizure of power by the Central Committee of the National Guard, which had just given its mandate back to the Commune. This, moreover, corresponded to the demand for the abolition of the standing army, common among the advanced wing of the republican movement and widespread among the opposition to the Second Empire. Indeed, the 'Belleville programme' underpinning Gambetta's election in 1869 had called the standing army a 'cause of ruin for the nation's finances and its affairs, a source of hatred among peoples and of domestic mistrust'.[59] These same sentiments would drive the Commune's single most symbolic action, the destruction of the Vendôme Column; the 12 April decree announcing this move termed the Column 'a monument to barbarism, a symbol of brute force and false glory, an assertion of militarism, a negation of international right, a permanent insult by the victors against the defeated, and a perpetual attack on fraternity, one of the three great principles of the French Republic'. It is worth adding, here, that the first decree on the abolition of the standing army was complemented by a further one in which the Commune ordered the 'employees of the various public services' to 'henceforth take for null and void all orders or communications emanating from the Versailles government or its members', explaining that 'any functionary or employee not confirming to this decree will be immediately dismissed'. The following day, in its electoral commission's report, the Commune refused all recognition of National Assembly's authority and issued a ban on dual membership of both bodies.[60] Tellingly, this same text proclaimed that foreigners — meaning, Léo Frankel — were admitted to its own General Council, 'considering that the Commune's flag is that of the Universal Republic' and that 'every city has the right to grant the title of citizen to the foreigners who serve it'. The Commune thus declared itself the only legitimate power in the capital and, calling on other towns and cities to rally to its side, established a de facto dual power situation nationally. Moreover, as Jacques Rougerie notes — citing the notification to foreign governments issued by its 'delegate for foreign relations',[61] Paschal Grousset — 'to settle an old debate, the Commune did indeed consider itself a government of the City'.[62] Its official organ's full title was Journal officiel de la République française — the official organ of the French Republic, not 'of the Commune', as historians often cite it. Yet the Commune refrained from touching the Bank of France's reserves, on the grounds that 'they belong to France'.[63] Here, we can see the fundamental uncertainty over the character of this new regime, even in the actors' own understanding. While some, reflecting on these events' meaning after the fact, considered that 'the Paris Commune expressed, personified, the first application of the anti-governmental principle', or that its 'its mission was to make power itself disappear, if it was not to betray its first pronouncements',[64] it still had to be recognised that very quickly 'it had become — deliberately or not — a government with its assemblies, its army, its Journal officiel, and when it did agree to deal with Versailles it did so as one government to another' (as Jeanne Gaillard puts it).[65] Decisively, this was a government based on a considerable military force — the Paris National Guard, with its almost 150,000 armed men, which 'always retained a deeply democratic and political character, and the trappings of a club or union'.[66] The fédérés elected both their officers and delegates who served as their spokesmen. They took initiatives and discussed the orders they had received — often rejecting them. Doubtless, this also served to undermine the National Guard's military efficacy and contributed no little to the final tragedy. But there is also no doubt that this is also the point where we see the Commune's clearest rupture with the state logic. Here we can again cite Robert Tombs, on the terrain where he is most reliable: 'the National Guard perhaps represented a rare thing in history: a genuine citizen army that citizens were bound to serve in, but without the high command having to force them; incapable of strict discipline, but having a sense of duty and solidarity; an unusual army that refused to use capital punishment to enforce discipline in its ranks'.[67]

While the Commune was an armed power, it set itself a resolutely anti-bureaucratic agenda. Marx cites two telling measures in this sense: firstly, the extension of the principle of election and recall to civil servants, including those who made up the repressive apparatus (the police and justice system); and, secondly, the introduction of a 'worker's wage' for all public service roles, even the very top posts. What evidence was Marx basing himself on, here? In the second case, he could simply draw on the 2 April decree in which 'considering that in a really democratic Republic there can be no sinecure or excessive stipend' the Commune 'decree[d that] ... the maximum stipend for employees of the various communal services is fixed at six thousand francs per annum'.[68] It has often been observed — sometimes rather wryly[69] — that this was around triple the salary of a skilled worker: the mean annual wage of a Parisian worker at the time was of the order of 1,500 francs, and that of a director of a municipally owned company (like the Tobacco Board) 4,000 — hence below the ceiling established by the new regime. It seems clear that, faced with the flight of a large proportion of upper-ranking management personnel — a classic problem in all revolutions —, the Commune sought to avoid any punitive pay cuts and instead stopped at vigilance against abuses and banning individuals from taking on multiple posts. It, moreover, sought to grant greater value to emblematic social functions, by doubling stipends for school teachers, which were raised to 2,000 francs a year; it also set at an equal rate for both men and women teachers. The Commune itself set a good example by fixing the allowance for its Council members at 15 francs a day (i.e. a little over 3,000 a year): an amount that Arthur Arnould judged 'more or less' equivalent 'to what an excellent, intelligent and industrious worker would earn in a good trade in Paris'.[70] There was doubtless a certain desire to reduce the wage gap: but the 'cheap government' cited in The Civil War in France owed more to the need to keep public services running with reduced numbers of personnel, and a determination to cut out corruption, than a levelling of salaries. Marx implicitly recognised as much, when he noted that '[t]he vested interests and the representation allowances of the high dignitaries of state disappeared along with the high dignitaries themselves.'[71]

Important though it was, the question of stipends nonetheless remained subordinate to another, more structural problem — the effort to make public functionaries 'responsible and revocable'. For Marx, this would make it possible to stop public functions being the 'private property of the tools of the Central Government'; 'Not only municipal administration, but the whole initiative hitherto exercised by the state was laid into the hands of the Commune.'[72] But on what grounds could Marx assert these principles — which, it is worth underlining, corresponded in good measure to the principles of self-government in the English-speaking countries, where sheriffs and a substantial share of magistrates were elected? The election and recallability of public functionaries and elected officials made up demands widespread among the forces who supported the Commune, and among advanced republican currents more broadly. The Committee of the Twenty Arrondissements, which resurfaced with its Manifesto published on 26 March, spelled out its great foundational principles (republicanism, fundamental freedoms, a full popular sovereignty based on universal suffrage) before setting out how they could be enacted:

The principle of election applies to all public functionaries or magistrates.

The accountability of those holding mandates, and, therefore, their permanent recallability.

Binding mandates, specifying and limiting the power and the missions of those who hold them.[73]

But even the 'Belleville programme' of 1869 — the banner upheld by the 'radical' wing of bourgeois republicanism — demanded 'the direct accountability of all functionaries' and the 'appointment of all public functionaries by election'.[74] The 19 March Declaration to the French People was less categorical in extending the election principle, but it did — decisively — add the principle of recallability. The Commune sought to establish 'The choice by election or competition of magistrates and communal functionaries of all orders, as well as the permanent right of control and revocation.'[75] Moreover, some of the socialist programmes that circulated during the 26 March elections for the Commune Council envisaged a combination of elections with established competitive recruitment processes.[76]

Of the two principles mentioned in the 19 April Declaration, the only one toward which concrete steps were made was the principle of competitive examinations, though even this was never truly put into practice. In reality, other logics guided the recruitment of the Commune's administrative personnel, from the informal (neighbours, mutual connections) to the more traditional (invoking expertise or 'objective' criteria like educational qualifications) or even more directly political ones. Historical studies well as some of the accounts by actors in the Commune (first and foremost, Jules Andrieu, the Paris communal administration's head of personnel from late March and from 20 April a delegate to the Public Services Commission) give more specific insights into the concrete functioning of the Paris administrative machine under the Commune.[77] The new government's main challenge was, quite simply, to provide for the vital functions of a large city under a state of siege, after a significant part of its functionaries had deserted it upon Thiers's instructions.

According to Lissagaray, the municipal services 'were all carried on with a fourth part of their ordinary numerical strength'— but this figure seems like a significant under-estimate, and it is also unverifiable.[78] We may think, like Gustave Lefrançais, that if the new regime initially had rather ill-defined ambitions (an assembly demanding expanded 'municipal franchises' in parliament, or else a real 'government' legitimated through revolution?) precisely what made it embrace its own role and radicalise was its need to take these concrete problems in hand: 'this decision by Versailles [to dismiss any functionary who did not leave Paris for Versailles] would bring us out of the framing that we had initially set ourselves and force us to stick our nose into state affairs ... We took to the broader path not of a simple communalist revolution, but of the real revolution; the revolution proposing not only the political and administrative emancipation of the communes, but also the economic emancipation of the workers — finally, the social revolution'.[79]

The question this poses then becomes: what progress in this direction did the Commune actually make? This is not an easy question to answer, considering both the brevity of this experience and the unique circumstances in which it arose (though it is also true that, by definition, any revolution is bound to be confronted by extremely adverse conditions). Andrieu's account gives an impression of great disorganisation, inefficiency and endless disputes over the limits of different areas of responsibility. But his comments are doubtless also coloured by his frustration at having seen his proposals for administrative reorganisation rebuffed — and, especially, by his own particular viewpoint as an administrator professing what we would today term a 'technocratic' conception of his job. Openly hostile to the principle of electing functionaries and the emphasis on social revolution, more than sceptical of workers' ability to take on management functions, and concerned to keep as many of the existing functionaries as possible in their posts, Andrieu demanded a greater centralisation of power in his own hands (he spoke of 'turning the Haussmann plan inside-out' and of 'using centralisation against itself')[80] even as he asserted the need for a mode of governance that combined centralisation and decentralisation and granted a large measure of autonomy to the municipal level. According to Andrieu, the 'national council' that he wanted to crown a future Republic's institutions should draw 'only on learned, philosophical minds of expansive culture'.[81] As Maximilien Rubel, who published this manuscript in 1971, soberly notes, 'Andrieu, both an actor and a judge, did not see the Commune as a workers' government and still less the negation, the abolition of the state'.[82] It is unsurprising that such a figure should have found himself in a doubly awkward position in insurgent Paris, caught between the decentralised and often confused logics of the action coming from below, and the lack of sufficiently assertive leadership from above. This situation led him to conclude that 'the Commune needed administrators but it was overflowing with men who wanted to govern it. The gap between the two is greater than that between a mathematician and a dancer'.[83]

Yet, according to other important accounts, the administration of the Commune was far from disastrous. Lissagaray, who was hardly prone to idealise the Commune and did not spare it from criticism on many accounts (its military affairs of course, but also its handling of police, justice and education) states that, overall, 'the municipal services did not overly suffer' and that they 'were managed with skill and economy ... by workmen, subordinate employees'.[84] Recent research by historians, taking as their sample the individuals prosecuted after the Commune for 'usurping public functions', also attests to this tendency toward the 'plebeianisation' of such posts.[85] Lissagaray draws a particularly positive assessment of the Albert Theisz's management of the postal service and Zéphirin Camélinat's handling of the Commune's money supply (both of these men were workers in artistic trades), as well as public welfare and health, the telegraphs, the national printworks, the services connected to finances, and, more generally, the Labour and Exchange Commission we have already spoken about in some detail. And it is worth underlining that everyday life went on without major impediments, despite the ever-tightening siege with its vice-like grip on Paris: the food supply remained stable, theatres, shops, cafés, museums and libraries were open and public safety protected. This is confirmed by accounts by contemporaries who stayed in the city over this period, far from all of them sympathetic to the Commune.[86] Ultimately, Andrieu himself was not ever so unhappy at the results of his work reorganising the cemeteries or ensuring the continuity of the gas and lighting service.[87]

If the Commune avoided chaos — certainly no mean feat — were the routines and the habits of the administrative apparatus which the new regime inherited actually transformed? Was there any concrete progress in carrying out the debureaucratisation mentioned in The Civil War in France? Here, the picture looks rather mixed. Elections for functionaries did not become a reality, or they did so only to a marginal extent, and plans for competitive examinations were also frustrated for lack of time. But telling in this regard were the written tests for those who had applied to become National Guard officers, held a week before the Versailles troops entered Paris; the choice of subjects expressed an evident desire to test out the candidates' political convictions, at least when it came to filling such sensitive roles.[88] But the Commune more drew on 'apolitical' criteria in its efforts to incentivise already-established functionaries to remain in post or to take on new responsibilities (like ‘serving the general interest', or keeping trust in a competent superior).[89] So even if, as Deluermoz and Foa suggest, there was a longer-term project to create a properly 'Commune' functionary who combined political loyalty and an impersonal logic of public service,[90] its definition appears at least rather fluid. Concretely speaking, the continuity of the city administration and public services was fulfilled through a hybrid logic of ad hoc reorganisation, militant mobilisation, informal means of recruitment, 'meritocratic' appeals to expertise... and a great deal of improvisation. Eugène Protot, a lawyer delegated to the Justice commission, had no time to implement the proposed reforms — there was even discontent that he had not immediately made the justice system free of charge. In some municipally owned companies, and, in particular, the postal service and the Louvre arms factory, there was a genuine attempt to promote workers' participation in management and to challenge the previous hierarchical relations. But the actual results on this second score are disputed; and, looking at the overall picture, these were exceptional cases. The Commune’s personnel’s concrete actions present a similarly mixed picture; they greatly depended on local and neighbourhood dynamics, whose decisive influence on Commune-era Paris can hardly be overstated. The logic of ad hoc revolutionary measures (for instance the requisition of housing and the arrest of priests) sat side-by-side with a — sometimes ostensible — respect for legal forms, but also a seemingly temporary redefinition of public functions and their remit. These practices had to be enacted in both hostile environments (as in bourgeois neighbourhoods) and more favourable terrain, in working-class areas, where 'the authorities seemed more integrated into the local fabric and the inhabitants' lifestyle ... and where the transformation of everyday relations went further, if not without friction'.[91]

This was especially true of policing. According to Marx, '[i]nstead of continuing to be the agent of the Central Government, the police was at once stripped of its political attributes, and turned into the responsible, and at all times revocable, agent of the Commune. So were the officials of all other branches of the administration'.[92] Such a claim clearly corresponds to the need to defend the Commune, in a time and a context where the Communards were presented as bloodthirsty criminals responsible for all manner of destruction and the mass execution of hostages. The reality is that the Commune had little control over the central policing institution, renamed the 'ex-prefecture'; it was entrusted to Blanquist cadres (headed by Raoult Rigault, then, from 24 April, Théophile Ferré) who were left to their own devices. This police mounted a necessary — if often ineffective — hunt for Bonapartist agents and Versaillais spies, but it was also prone to arbitrary acts and excesses, in particular, anti-clerical attacks. This reflected both a certain Blanquist obsession and the 'priest-hatred' that so animated the Parisian popular classes of the time. In early April, Lefrançais and Delescluze demanded Rigault's immediate replacement, while Protot, himself an ardent Blanquist, took a number of initiatives to limit Rigault's power, ensure respect for procedure during arrests and release people who had been arbitrarily arrested. Lissagaray and Andrieu, among others, passed a very severe judgement on the police's work.[93]

But it would be illusory to imagine that the 'ex-prefecture' controlled everything that was going on in the city. On the ground, a form of 'citizens' police' was created in the neighbourhoods sympathetic to the Commune, combining police commissioners with National Guards and local residents. If these self-organised security functions generally did allow for public safety to be protected, they also gave rise to abuses and — allied to a certain vagueness over legal procedures — a form of 'complete politicisation of social life' that even led at times to personalised score settling.[94] But we should be careful not to exaggerate the extent of such practices. Somewhere between 1,400 and 3,500 people were arrested at some point during the two months of communalist power[95] — and this in an insurgent city with almost two million inhabitants, under siege conditions and a permanent state of military confrontation.

Overall, then, the landscape of the real transformation of the state machinery under the Commune appears rather uneven, also foreshadowing in that respect certain important features of the revolutionary experiences of the twentieth century. On the one hand, we can see a sharp rupture in the repressive apparatuses (except for the judiciary), and even a radical rupture when it came to the army — the sole case where we can say that a new institution built on citizens' self-organisation took over from the old apparatus. But this came at much too high a price in terms of military effectiveness; the Commune's military high command proved technically but — even more importantly — politically incapable of commanding a popular army of this kind. The transformation of the administrative machine was far more modest and largely appears the product of circumstances imposed by the government's flight to Versailles and the pressure imposed by the new siege. This machine's actual effectiveness was more satisfactory, though also mixed: its political mobilisation ensured the continuity of the services essential to the capital's social and economic life, notwithstanding the unprecedented difficulties posed by this situation. All the same, elements of qualitative transformation did begin to emerge, with a strong tendency toward the 'plebeianisation' of upper administrative positions and some — limited, but real — cases of the democratisation of public services and municipally owned firms.

Changing power: from communal autonomy to the producers' self-government

Much more than the organisation of everyday life or the development of the city administration (apart from the role of the National Guard) the key focus of contemporaries' attention was the institutional dimension of the Paris Commune's project, as expressed by its very name. Marx's portrayal of this question in his The Civil War in France, which was largely based on the 19 April Déclaration, centres on two structuring ideas.

First, a rupture with what we might call 'parliamentarism'. Based on the principles of binding mandates and the recallability of elected representatives, this rupture sought to reduce if not abolish outright the distance created by relations of representation. This change was allied to the Commune's determination to transform the functioning of the communal assembly itself, by making it 'a working, not a parliamentary body, executive and legislative at the same time.' These were complemented by another principle which Marx credited the Commune with having accomplished; namely, that of making its debates fully public and thus allowing for mistaken decisions to be rectified.

The second idea was based on the principle of a radical decentralisation of power. This underpinned the idea of the Commune as the 'direct antithesis to the Empire' and its oppressive and corrupt centralising state. This principle of communal autonomy would then be generalised across the national territory, allowing a refoundation of national unity from below. This institutional architecture was to be crowned by a pyramid-like system of delegation based on universal suffrage; this was meant to take in hand the 'few but important functions which would still remain for a central government'.

It is difficult — and largely pointless — to try and separate Marx's ideas from the Commune's own, a large share of which were also shared among republican currents more generally. Both decentralisation and distrust toward parliamentarism were recurrent themes in the democratic and socialist thinking of the time. These sentiments expressed the lessons of the failure of the republic which had emerged from the 1848 revolution, which saw an assembly elected by (male-only) ‘universal’ suffrage crushing the insurgent workers in the June Days, and then committing to an authoritarian, conservative path which directly led to Bonapartism. Marx thus damned 'parliamentarism' by noting that 'its last term and fullest sway was the Parliamentary Republic from May 1848 to the coup d’état. The Empire that killed it, was its own creation'.[96] But, in so doing, he was voicing a conclusion to which many republicans well beyond socialist ranks could have subscribed.

The ardent desire for a Republic and genuinely ‘universal’ (although still male) suffrage was not, therefore, synonymous with blind faith in the virtues of a parliament. Or, more accurately, it did not imply any illusion that such an assembly would alone suffice to make a democratic system viable, not least given that the Second Empire had itself restored a façade of parliamentarism with a bicameral system that preserved the reality of Bonapartist power. The idea of strengthening the power of the communes (municipalities) — the basic unit of the French institutional structure since the Revolution — thus appeared as a necessary means for endowing a republican order with deeper roots, especially given that throughout the final decade of the Empire the cities had constantly expressed their own republican impulses. This process can also be read as a translation of France's socio-economic and institutional transformations under the Second Empire, as expressed in the progress of urbanisation, the consolidation of a provincial bourgeoisie and — helped by the regime's own liberalisation measures — the growth in the political importance of the municipal tier of government. This made its suppression in the capital all the more difficult to tolerate.[97] The commune as an idea — from the municipal commune to the Paris capital-C Commune —was thus a shared point of reference for all forces seeking a political form that could be a true 'antithesis to the [Bonapartist] Empire' and its centralising and oppressive state.

But, while both the Commune and Marx's reading of it made up part of a broader movement, they nonetheless proposed a radicalised and properly revolutionary version of these ideas. This marked them apart from bourgeois republicanism, even in its most advanced variants. The cleavage is well illustrated by Marx's idea of a communal assembly as a both legislative and executive working body. This is sometimes reduced to a straightforward denial of the classic constitutionalist separation of powers; according to the champions of political liberalism, it allows us to glimpse an authoritarian or even totalitarian propensity in Marx's thinking.[98] Some Marxists lean in the same direction, seeing in this formulation 'a confusion between the notion of the withering away of the state as a separate body parasitic [on society] and the notion of the disappearance of politics in favour of a simple self-administration of things or social life'.[99] In this view, Marx sought to fuse administrative and political functions, and in practice this meant collapsing the latter into the former in order to produce what Engels famously called in the Anti-Dühring a simple 'administration of things'.[100] On this reading, for want of a proper distinction between the two kinds of functions, this depoliticising vision had ultimately served as a justification for ever-expanding bureaucratisation under Soviet socialism.[101] Yet, as we have seen, Marx saw the Commune as a 'thoroughly expansive political form' making it possible to wage the fight for the emancipation of labour — so, quite the opposite of a technocratic depoliticisation of social life. As for bureaucratic functions, the point was not to abolish them — that is, when they were necessary to social life itself — but rather to debureaucratise them by setting them under popular and public control. This was the alternative to abandoning the monopoly on these functions up to a hierarchical caste of functionaries, concerned to defend their privileges and working at a remove from of any kind of scrutiny by society.

To better understand what Marx meant by this formulation, we should begin by clarifying what he meant by the — obviously pejorative — term 'parliamentarism'. [102] Indeed, this term referred not to the existence of parliaments, or to their power, but rather to their impotence, which resulted from the structural transformations of the bourgeois state over the course of its historical evolution. A passage in the first draft of The Civil War in France well summarises this idea: 'the State machinery and parliamentarism are not the real life of the ruling classes, but only the organized general organs of their dominion, the political guarantees and forms and expressions of the old order of things.'[103] In other words, the true centre of the ruling class's power, the place where its real policy was articulated, was neither the bureaucratic machine nor parliament, even if this was the site where it had first asserted itself in the early phase of the bourgeois revolutions in Britain and France. But where was it, then? In the executive, which now dominated the legislative branch of government and concentrated political decision-making in its own hands, protecting it from popular pressure far more effectively than any assembly could. This was the mechanism that had led the Constituent Assembly of 1848 to scuttle its own authority and pave the way for Louis Bonaparte, the very incarnation of the all-powerful executive. As Marx put it, 'In their uninterrupted crusade against the producing masses, they were, however, bound not only to invest the executive with continually increased powers of repression, but at the same time to divest their own parliamentary stronghold – the National Assembly – one by one, of all its own means of defence against the Executive. The Executive, in the person of Louis Bonaparte, turned them out. The natural offspring of the “Party of Order” republic was the Second Empire.'[104] In this sense the critique of parliamentary impotence was related to the denunciation of 'parliamentary cretinism' — i.e. the outlook of those trapped within the exaggeratedly dramatised forms of political representation. The Eighteenth Brumaire had mocked this as 'that peculiar malady which since 1848 has raged all over the Continent ... which holds those infected by it fast in an imaginary world and robs them of all sense, all memory, all understanding of the rude external world'.[105]

Conversely, the idea of an assembly as a 'working body' referred to the experience of the assemblies of the French Revolution. Marx had studied them closely in his youthful writings, and planned to write their history.[106] For him, these assemblies embodied the primacy of legislative power, the site for the articulation of a popular will that always exceeded its forms of representation - as he put it, 'legislative power produced the French Revolution'.[107] This primacy was further expressed in these assemblies' ability to establish their own supremacy over the executive. To put it in the terms of The German Ideology, the 'essentially active Assembly' — the National Assembly — owed its capacity for action to the pressure that the popular masses had exerted upon it, to which it had had to bend (willingly or otherwise),[108] ‘actually transform[ing] itself thereby into the true organ of the vast majority of Frenchmen'.[109] In his notes on Levasseur — a former National Convention[110] member from the Sarthe — in 1844, as he was working on plans for a history of the Convention, Marx more systematically explored the three-way relations between legislative power, popular movement and executive power. Marx's attention was particularly drawn to the exemplary period in which real executive power had come into the hands of the 'popular movement'. Taking down excerpts from Levasseur, Marx especially noted that the 'popular movement' — a key term in Jacobin discourse — had found organised expression in another elected body, the (first) Paris Commune. This was the Paris Commune of the sans-culottes and Pierre-Gaspard Chaumette, which continued to exercise authority over the Convention that followed the Girondin-dominated assembly: 'An interregnum begins on August 10, 1792. Impotence of the Legislative Assembly, impotence of the Ministry to which it had given rise. Government passes over to the public meetings and municipalities; improvised centres of government, products of anarchy, they were bound to be the expression of the popular movement, for their power was only the power of popular opinion ... The Provisional Council of Ministers, entrusted with executive power by the Gironde on August 10, was powerless "since the party on which it depended had made itself unpopular", "executive power was in fact exercised by the Communes, especially by the Commune of Paris, composed of men of vigour and beloved of the people. The elections in the capital took place under the influence of the Commune whose leading members were elected”.[111] The Convention itself only managed to become a real 'working body' thanks to this constant interaction with the popular movement and its multiple forms of expression, be they informal or organised. In a passage copied down by Marx, Levasseur relates this in disapproving yet powerfully evocative terms: 'The committees of the Convention and the Convention itself dealt with all the branches of administration and performed through decrees numerous and frequent acts of executive authority. On the other hand, the municipalities had also taken over a large section of the administration. Civil power, military power, even judicial power, nothing was properly organised ... As soon as, for any reason whatsoever, a gathering of citizens was called upon to deal with a matter of public concern, it would at the same time interfere in matters quite unconnected with the task it had been given.... If there existed an infinity of powers in practice, a single collective entity, the Convention, legally united in itself all the authority of the social body, and it frequently used it: it acted as the legislative authority through its decrees, as the administration through its committees, and besides it exercised judicial power through the manner in which it extended the right of indictment'.[112] From one revolutionary Commune to the other, here was a striking game of mirrors between Marx's reflection and the conjunctures to which it related, themselves reflected in the fundamental unity of the great revolutionary sequence which began with the victorious uprising of July 1789 and ended in May 1871 with the massacre of the people of Paris. So, it is no surprise that Marx saw the 1871 Commune as a 'working body' insofar as, like the 1792 Commune, it was the emanation of the popular movement. That was the source of its strength — and it internalised this strength in its own structure, as it went beyond 'parliamentarism' to become simultaneously both a deliberative assembly and an executive power, even if only at the level of a single city.

Here, Marx was basing himself on the fact that the near totality of the Commune Council's members were also members of one of its nine executive 'commissions'. René Bidouze notes that the Commune 'was a "representative" assembly each of whose members had been delegated their powers by the electors'[113]—we will discuss later the question of binding mandates and the extent to which they alter the representative principle. But elected representatives' role went beyond that of a traditional MP limited to making laws, since the Commune Council's members took up hybrid functions which also reflected this assembly's dual character as both a municipal council and a revolutionary government. But this was also its downside: for the Commune's main internal weakness doubtless lay in its demonstrable inability to become a true 'working body'. This was not, of course, because it had become the plaything of the executive like bourgeois assemblies had, but because it failed to fit itself out with a functioning executive organ, even one subordinate to it. The sentiment soon took hold that the Commune Council was getting lost in discussions not followed up by concrete results, and that it had not provided itself the means of applying its many decisions. Marx, informed by his correspondents, was perfectly conscious of this situation, as his 13 May letter to Frankel and Varlin indicates.[114] Part of the difficult lay in the dual-power situation with regard to military matters: the Central Committee of the National Guard constantly challenged the authority of the Commune’s Council and, on top of this, it had itself to grapple with battalions often little-inclined to accept authority from above and which, given their well-established self-organisation, also had effective means of asserting their autonomy. But it soon became clear that this problem extended much further, and that the commissions structure was inefficient. The excessive number of (ill-defined) functions, their overlap and unstable composition, the lack of coordination between commissions, and the various conflicts between them fuelled incessant debates on the need to reorganise the executive. Following a text by Delescluze, adopted on 20 April,[115] 'the Council decided to replace [the Executive Commission] by the delegates of the nine commissions, amongst whom it had distributed its different functions.' These delegates, elected by a majority of votes within the Council, would 'meet each day and take decisions relative to each of their departments by a majority of votes' and 'report to the Commune each day, in a secret committee, on the measures they had decreed or executed, and the Commune would rule on them'. Here we see both the determination to build a distinct, compact executive to which the Commune could 'delegate' what it called 'executive power', and the determination to keep tight control over it. We can also note the straining of the principle of publicity. In truth, this principle was always the object of bitter disputes between those who saw this as a constitutive element of the democratic principle and those (especially among the Blanquists and those considered as 'Jacobins') who opposed this, citing exceptional circumstances or the need to streamline the Council's deliberations (indeed, a large part of its sittings was devoted to discussing the minutes of the previous ones). The Journal official only began to publish reports starting with the 14 April sitting — minutes that Lissagaray considered 'abridged' and giv[ing] but a very vague idea of these sittings'.[116] Many secret sittings continued to be held, even in the face of the opposition of many Council members.