A Story of the Chinese Countryside

In this excerpt from China In One Village, Liang Hong illustrates the problem of separated couples in the Chinese countryside through the tragic story of a rural woman's suicide.

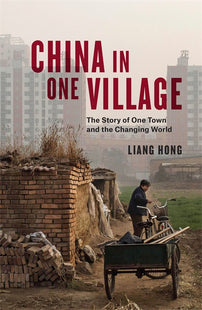

An excerpt from China In One Village: The Story of One Town and the Changing World by Liang Hong. After a decade away from her ancestral family village, during which she became a writer in Beijing, Liang Hong started visiting her hometown in landlocked Henan province. What she found was an extended family torn apart by the seismic changes in Chinese society, and a village hollowed-out by emigration, neglect, and environmental despoliation. Combining family memoir, literary observation, and social commentary, Liang Hong’s moving account became a bestselling book in China and brought her fame. China in One Village tells a world-historical story through one clear-eyed observer, one family, and one village.

****

Chunmei

Summer 2008 seems especially hot. At noon I chat with my brother and then go upstairs to organize the tapes from the past few days. They took a lot of time and work, but the results aren’t good. Sometimes there are a lot of people around, and their loud voices drown out my primary interviewee. And more than once we end up talking about something other than what we’d planned. But the diversions are also interesting, with new, unexpected things unearthed.

All of a sudden, my sister-in-law runs in saying “Hurry, come and see, Chunmei drank poison!” And then like a whirlwind she is gone.

I take off my headphones and can hear all sorts of noises and the sound of weeping in the front courtyard. People are shouting, Chunmei, Chunmei, wake up, wake up! I hurry downstairs and see my brother taking something out to the woman lying in a wheelbarrow and pouring it into her mouth. It must be something to empty her stomach.

Chunmei is unconscious, but she looks as if she’s in pain. Amid the sounds of her rescue, her eyes flicker from time to time, and it seems she might be responding. The attempts to revive her are successful; she seems to be regaining awareness. She opens her eyes and looks around, and then suddenly grips her mother-in-law’s hand tightly. In a hoarse voice she says, I don’t want to die, I want to live, I don’t want to die, save me, I’ll be good. She says it again and again and then loses consciousness, her hand still gripping her mother-in-law, as if it were the lifeline that might save her.

In the short time she was awake, she also managed to spit out: If I live, I’ll make you a new pair of shoes.

An hour later Chunmei’s feet twitch a few times and then all movement stops. My brother checks her pulse and shakes his head. She is dead.

I silently withdraw. Over the next few days, Liang Village, which is usually so quiet, bursts with noise, and for the first time, Chunmei’s house, on the east side of the village, becomes the center of town. People gather around the door or stand beside the pond, discussing what happened. A few Liang family elders gather in my cousin’s home and talk for a long time. They first decide to send a few senior members to inform Chunmei’s family. After that they begin to discuss the burial. Her husband doesn’t work in the village, and it will take him three or four days to make the trip; the weather is so hot, it will be hard to reserve the body. Then Chunmei’s father, mother, brothers, and other family members, about twenty or so, arrive crying and cursing, armed with sticks and hoes. They break all the pots and pans in Chunmei’s mother-in-law’s house, and then they go after my uncle and his wife. They won’t allow the funeral. They insist on waiting for her husband so that he can give an explanation. So we send someone to get him.

Her husband, my cousin, is nicknamed Ge’r: “Rooty.” He graduated from middle school and is one of the few from the village who works in a coal mine. He doesn’t have a phone, and he never left the number of the mining company, but he comes back every year for harvest and Spring Festival. Only now does everyone realize that there is no way to contact him. They bundle a young man from his family onto a train to go find him. “Escorted” by Chunmei’s older brother, my uncle goes to buy the best coffin and a large quantity of ice to put around it, to keep down the intensifying smell.

Chunmei was tall and one of the prettier young married women in the village. Her round face and her large eyes were always alert and curious. But she wasn’t popular; she was both strong willed and relatively incapable. She didn’t get along with other women, and when they passed on the road, they’d give each other dirty looks. Yet when Chunmei died, the women were deeply shaken. They gathered in groups, talking about it. The curious thing is, they immediately stop talking when I join them and just look at me guardedly before changing the subject. Perhaps there is something I don’t know. It’s true I don’t really know these young women; I left before they got here. Later, my brother tells me that Chunmei is closest to the wife of one of our cousins. She was Chunmei’s only friend in the village. My brother introduces us; she is a high school graduate who has her own views and relatively modern ideas. I ask her for an interview and learn the reason for Chunmei’s suicide.

I am telling this only to you, you must never tell anyone else. I’ve been so unhappy these past few days, so troubled. I blame myself for Chunmei’s death. I had a part in it. Before Chunmei and Ge’r had been married a month, he left to go work. Normally Chunmei would have gone with him, but she gets carsick—when she rode to the county seat, she nearly died from vomiting—so she said she wouldn’t go for anything, she didn’t dare take the train. Later she had a little girl, so then she really didn’t want to leave. Although Chunmei was short-tempered and often fought with her mother-in-law and with others in the village, she had a really good relationship with Ge’r. I never saw them fight. When Ge’r came back, he would ride his bike around with their daughter on the front and Chunmei on the back. They would go to market in town or to visit Chunmei’s parents or to see relatives. Sometimes they left their daughter with his mother, and the two of them would go into town for a date. They rode the bike, one carrying the other. They were really close.

People might say that Chunmei didn’t know much and that she was a little dumb, but they also knew she was hardworking and tidy. She worked all day long, and their two little rooms were always neat and clean. There wasn’t a speck of dust on the beds or tables. When she went to work in the fields she gave it her all, and at home she raised chickens, ducks, pigs, and for a while also rabbits. She worked too hard, really. Her greatest wish was to build a large house like Huan’s and not to live crammed in with her mother-in-law.

This year things changed for Chunmei. Ge’r didn’t come back for Spring Festival. He called the former village secretary to say that the mine needed someone to guard it, and the pay was doubled, so he planned to stay. Chunmei hadn’t been able to get to the phone, and she was feeling resentful. You don’t know, but the last time Ge’r came home was last year at Spring Festival. He didn’t come back for the midyear harvest, and now he wasn’t coming again. If he came for the summer harvest, it would be a year and a half that he hadn’t been back. Chunmei was heartbroken, and she hit her daughter, swore at the animals, and glared at people. Sometimes she would close the door and not go out for the better part of the day. Who shuts their doors in broad daylight in the village? Her mother-in-law wasn’t happy about it and said she couldn’t live without a man. Chunmei made it worse, saying who says you don’t need a man, you’re out and about every night. Her mother-in-law was so mad she couldn’t speak. Actually, her mother-in-law is a Christian, and she’s always away from home. At New Year’s, when others are all together, the young couples visiting their relatives, Chunmei is left all on her own. It wasn’t easy for her.

After the New Year, Chunmei came over to chat, and we started talking about this. At first she was embarrassed, but finally opened up, and she cursed Ge’r up and down. I could tell she actually just missed him. So I gave Chunmei an idea. What if she wrote him a letter, saying she was sick and asking him if he would hurry home. At first Chunmei was too embarrassed and said she couldn’t write him a letter; they’d never written letters before. Ge’r had gone through senior year of high school, and he can write and read the newspaper. But Chunmei was mostly illiterate. How could she write? I said if you can’t write, I’ll write for you. I’m a high school graduate, for better or for worse, and I’m pretty romantic. When your cousin was working as a sailor down south, we would often write letters and send each other pictures. It was great. Every time a letter came, it made me so happy, no matter how tired I was. Chunmei knew we wrote letters, she envied us for that. Eventually, she agreed. So I wrote a letter to Ge’r for Chunmei, making it just a bit more expressive. After I was finished, I read it to Chunmei. When she heard what I wrote she yelled: Who says I miss him? But she didn’t tell me to change it. So I finished it and sealed it and addressed it, and Chunmei took it over to the town post office and mailed it.

After this, things started to get bad. The next day, she started waiting for a response. She sat at the village entrance every day, or sometimes even over at the post office. As soon as she saw the postal carrier, she would follow him around, afraid other people would know what was happening. She also wanted to drag me along. I told her, it takes more than twenty days for a letter to get there and back. But she wouldn’t listen, and after more than a month there was still no response. I started to think, maybe the letter had the wrong address. It didn’t seem likely. We had copied the return address Ge’r used when he sent money. Whenever she had a free moment Chunmei would come over to ask: What’s going on? What’s going on? I said, Why don’t we write another letter. Maybe the last one went to the wrong place. So I wrote another letter, and I had Chunmei take a picture to put in for Ge’r to see and write back. In retrospect, I was probably trying too hard, I should have just tried to comfort her. I added fuel to the fire and led Chunmei into a dead end.

This time she waited more than twenty days but Ge’r didn’t even write, much less show up. Chunmei stopped coming to me, and when I went to see her, she barely acknowledged me. She sat at home with the door closed all day long. She didn’t pick the peppers. She didn’t clean the floor. When her mother-in-law criticized her, she didn’t bite back like before. I was really worried, so I secretly wrote Ge’r a letter, and I even went over to the former secretary’s house and asked him if he could look up the number Ge’r had called from, but his phone didn’t display incoming phone numbers. I looked online, too, but I couldn’t find the mine where Ge’r worked. You tell me, what else could I have done?

Before, when Chunmei and I would go to market, she was always arguing with the people who sold clothes or the ones who sold shoes or apples. She always did. She was as noisy as hell. But now she didn’t say a word. Her eyes were empty, and she just bought whatever was in front of her. She was so meek. Her face was red and her hands damp and hot. Then for a while she became crazed. She fought with everyone she saw. Her husband’s grandfather, her mother-in-law, her daughter, she nearly burnt all those bridges. And no one knew why.

Her mother-in-law said she was “love sick,” that she missed her man so much she’d gone crazy. The two of them fought, and her mother accused her of this in front of other villagers. She had no face left after that, so she just locked herself in her room and didn’t come out. But it seemed like her mother-in-law was right: for the past two months she hardly had been able to work. She was always confused, and more than once when she went down to work in the fields she set her daughter down and then came back without her. She also stopped cooking, and when she saw a man in the village she ran as if he wanted to catch her. You could see things weren’t right. People started to stare at her and talk about her behind her back. It pissed me off, too, and when they asked me about it, I told them to back off. But what could I do? Ge’r didn’t contact us. This didn’t necessarily mean something was wrong; it’s normal not to be in touch. Who’s in touch unless something’s wrong? When it’s time, they came back on their own.

I thought we’d better wait it out until next harvest. Ge’r would surely come back then. But that stubborn bastard still didn’t come back. Now, last year Ge’r didn’t come back at the harvest either. Everything is mechanized now—the machines just bag everything up and deliver it, and you don’t need a lot of laborers. But here things were different. Chunmei wasn’t going to last much longer. She would die from it. She had repressed it until it made her ill.

Still, all that wasn’t too bad. To put it coarsely, in the spring the cats all yowl. People are the same. You just push through it. But a few months ago, something happened in Wangying, a neighboring village, and Chunmei started to dwell on that. A young married woman hung herself. Why? Her husband came back, and the two of them got along beautifully. They were always together, for a dozen days or so. For a month after he’d left again, this woman’s nether regions were always itching. But she just put up with it—she was too embarrassed to go see someone. But then she started to have a fever, and she had to go to the doctor.

They took a look and said it was a sexually transmitted disease. They also asked her who her husband had had contact with, and they drew blood to see if she was HIV-positive. All the villagers knew about it, and the woman was so ashamed and angry that she hung herself.

Now what does this have to do with Chunmei? As soon as Chunmei heard, she came over ranting like someone possessed. She pressured me, asking if Ge’r had done something bad. Is that why he doesn’t come back? I said how was I supposed to know. And I said at the mines, it’s all men. There aren’t any women there. Chunmei said, no, she saw it on TV, the mines are surrounded by women, they do that professionally, and they were sure to have diseases. She wouldn’t listen to my explanations, so I said, take your daughter and go find Ge’r. Don’t all the large mines have places for families now? Or rent a house and live there. As soon as I said that, Chunmei collapsed. She’d never left home, she’d be confused and lost, scared to death, and besides, if she spent months and years searching for Ge’r, everyone else would laugh at her. And she didn’t want to leave her land, she’d been working hard growing hot peppers and mung beans, and she was going to spread some fertilizer for turnips and cabbage. Ge’r didn’t earn enough to build a house, how could she give up the land?

Chunmei didn’t bring up the idea of going to find Ge’r again. But from time to time she’d go over to Wangying and wander around, asking about where the man worked, what the woman was like, how they’d caught the disease. She would come back and ask me again, if he’s with another woman will a man get sick for sure? She was jittery and unstable, and it made me feel bad. You see, your cousin works elsewhere, too. As a sailor, he’s been to every port, and what port doesn’t have that kind of place? I’d never thought about it before. It’s not easy to earn money, and who has the spare time and money for that? But lots of people can’t help it.

Three days ago she had a big fight with her mother-inlaw. I’m not sure about what. After the fight, Chunmei went to the fields to spread fertilizer. But when she got back she suddenly realized she’d spread it on the wrong fields. She’d spread two whole bags of fertilizer on someone else’s fields. She ran back and walked in circles around the edge. She didn’t look right to me, and I followed her. But on the way back she suddenly disappeared and went and drank insecticide. I said, are you stupid or what, so many men work outside the village, if we were all like you, would there be anyone left?

Ge’r comes back three days later with the man who had been sent to find him, and Chunmei’s family comes again with their anger. In the heat of the moment, Chunmei’s elder brother even slaps Ge’r a few times, but Ge’r just stands there, back straight. He doesn’t hit back and he doesn’t wipe away tears. He seems to have no tears. Perhaps he is numb or in a state of shock. He doesn’t seem to understand why his wife killed herself when their lives were getting better and better. I don’t approach him, even though I really want to ask if he received Chunmei’s letters. If he had, why hadn’t he written back? And communication is so easy now, why didn’t he have a cell phone? Didn’t he miss Chunmei? Didn’t he miss her body, still smooth and full?

But then again, what’s the point? To the villagers, it isn’t that big a deal. It isn’t the New Year or spring planting season, or fall harvest, so of course he couldn’t come home, that would be inconceivable. It would just be a waste of money. And to express feelings and emotions, that’s even harder. They’ve developed the ability to “repress” themselves. Issues of sex and the body are things that can be ignored. Yet how many hundreds of millions of people are part of this migrant army?

Would it be too difficult to consider this “small” question?

With reform and opening up, “export labor” began to influence the local economy’s major targets, because only people who leave to work can earn money, and only this money can drive the local economy. But how many partings and reunions, how much emotional turmoil comes as a result? How many lives are ground down to nothing? This never seems to be factored in. Men leave the village. They come back once a year or at most twice. Never more than one month per year total. They are all young or in their prime, when their physical needs are most intense, and yet they repress those needs for long periods of time. Even if husbands and wives work in the same city, only very rarely are they able to live together, simply because construction sites and factories are not required to provide married housing. And because it is very difficult to rent a place on their salaries, they often live at their respective workplaces. So even on the weekends, where can they meet? Where can they be intimate? It’s a hidden question that is hard to discuss; if they’re living in the same city, they are already considered fortunate.

This sexual repression has created many different problems in rural areas, and rural morality is on the verge of collapse. Migrant workers masturbate or visit prostitutes to relieve their needs. Some even form temporary new relations at their work sites. This causes an increase in sexually transmitted diseases, remarriage, illegitimate children, and other kinds of serious social problems. Women who remain in the villages must also repress their sexual urges; some turn to affairs, incest, and sexual relations with other women. This, in turn, allows the seedy side of the village to flourish. Some men use it as a pretext to sexually harass women, often successfully. Cadres are said to have “three wives and four concubines,” and many criminal cases arise from women’s jealousy and rivalries.

The general disregard for the sexuality of peasants also reveals a kind of deep discrimination. Our government, media, and intellectuals, in their inquiries into migrant workers’ problems, usually discuss wages and only rarely sex. This suggests that if the workers were allowed to earn more money, then all their problems would be solved. Or that if their wages were much improved, issues of sexuality and intimacy could be intentionally ignored. But why? Don’t these migrant workers have the right to both earn money and to live together as husband and wife?

They finally hold Chunmei’s funeral, and she is buried in the field where she hadn’t spread her fertilizer, her own body given to enrich this soil. On the seventh day, Ge’r goes to Chunmei’s grave and lights firecrackers for her. Then he leaves to return to work.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]