The End of Cinema

Jean-Luc Godard, the pioneering director who died on the 13th September at the age of 91, began his career with a pioneering series of films, a magnificent run that included the masterpieces À bout de souffle, Vivre sa Vie, Bande à part, Pierrot le Fou, Masculin Féminin and Week-end. Jared Marcel Pollen charts Godard's early career, and the intersection of literature and cinema in it.

Between 1959 and 1967, Jean-Luc Godard made 15 feature films, a magnificent run that included the masterpieces À bout de souffle, Vivre sa Vie, Bande à part, Pierrot le Fou, Masculin Féminin and Week-end. This era, from when Godard first started making films to the beginning of his revolutionary period, constitutes perhaps the greatest series of films made by a single filmmaker. These years saw an accelerated transformation in cinema, when the way in which films were made, and what films could be expected to accomplish, changed radically. It was also during this same decade that novels in France became less “interior”, more cinematic, in the hands of writers like Alain Robbe-Grillet, Nathalie Sarraute and Marguerite Duras, just as films were becoming increasingly literary. And it was this moment that Godard––who frequently characterized himself as a novelist who made movies––emerged.

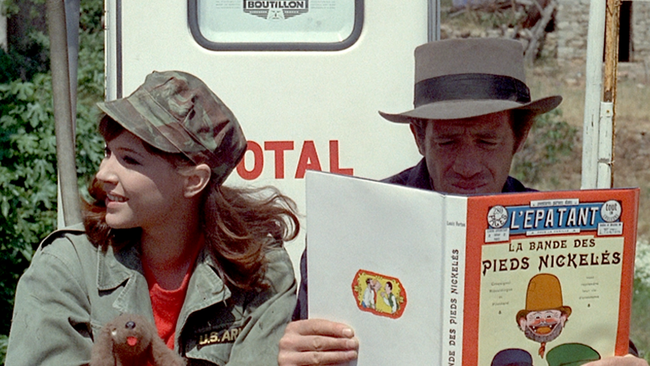

If we can compare Godard’s work during this period to anything, it would be the novels of Thomas Pynchon and James Joyce. Unsurprisingly, Godard often cited the latter as a key influence. In Pierrot le Fou, the character Ferdinand (played by Jean-Paul Belmondo), a failed writer and a stand-in for Godard himself, breaks the fourth wall, reading aloud from Godard’s own notebook as he explains to the audience his concept for a new kind of novel: “Not to write about people’s lives anymore,” he says, “but only about life—life itself. What lies in between people: space, sound, and color. I’d like to accomplish that. Joyce gave it a try, but it should be possible to do better.”

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]At the same time, Godard was attempting to achieve on the screen something that he believed only novels had the ability to do: to assimilate all styles, all voices, and all cultural materials, much as Joyce had done fifty years earlier. As Susan Sontag noted, rather than look to literature to adopt the conventions of plot, narrative and characterization, as the cinema had attempted since the silent era, Godard found a way to incorporate the heavy ideation and undramatized intellection that had always been easily assimilable into novels and into films only extraneously. More than that, Godard approached filmmaking as a gesamtkunstwerk, a medium that could not only integrate other forms, but also make them essentially cinematic in nature.

Ferdinand’s (i.e., Godard’s) description of a novel that would attempt to depict “life itself” is surely a reference to Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. In both books, Joyce fashioned a universe in which everything was usable. The novel, as he conceived it, was the ultimate container, the dumping ground for all culture. Godard took this notion and applied it to his films, throwing in literature, music, painting, comic books, advertising, criticism, journalism, news headlines, radio broadcasts and dance numbers. “One can put everything in a film,” he once said. “One must put everything in a film.”

At that time, the longstanding divisions between high and low culture were also beginning to collapse. Consumer society and its attendant commodification of everyday life had rendered everything déclassé. Signs of this devaluation had first appeared during Joyce’s lifetime, and appropriately, one of the central images of the Wake is a rubbish pile. (We also see this, correspondingly, in Walter Benjamin’s image of the collector and the ragpicker.) So too in Godard, culture is treated as a kind of trash (one of the title cards at the beginning of Weekend reads: “a film found in a dump”). The corollary of this is that everything, from Marx to Coca-Cola, is leveled. All is now equally exploitable. This is true even of ideas––“things” as much as anything else, which can be picked up, put down, plagiarized and discarded.

Godard was another well-known scavenger. One of my favorite anecdotes about him from Richard Brody’s biography, Everything is Cinema (2008), is the way he would pick up books in the store and read only the last few pages. He would often get ideas for films by reading just the dustjackets. When he “adapted” King Lear in 1987, he apparently didn’t even read the play. He needed only a premise, because a premise could be stolen, hijacked. Genre was merely a convention (Breathless as true crime, Alphaville as sci-fi, Bande à part as outlaw-romance) to be disregarded. It might surprise some to learn that most of Godard’s films from the 60s are based on novels (Contempt on Moravia’s A Ghost at Noon, Pierrot le Fou on Lionel White’s Obsession, Bande à part on Dolores Hitchens’ Fool’s Gold) but none of these films show much fealty to their source material. They were merely prompts for Godard’s energetic dilettantism and spontaneous experimentalism, containers waiting to be filled with whatever ideas were preoccupying him at the moment.

The rate and pace at which these materials are delivered reflects the liquidity of the culture industry that is constantly throwing one thing in front of another for our attention. You never have time to fully absorb anything in a Godard film. There is a paradoxically exhaustive quality to this; everything is given attention, but nothing is ever seen through to its conclusion. Voices come in and out, images flash across the screen, music starts and stops, characters read from books and then put them down, a line of action will begin before being cut off abruptly. Nothing is nailed down, everything is in flux, and there is never any sense, as Frederic Jameson once wrote, that any of these materials “will be put back together by the spectator in the form of a message, let alone the right message.”

[book-strip index="2" style="buy"]Indeed, the search for a message is a constant in Godard, especially for those viewers new to his work. This feeling is often elicited via formal experimentation––the ponderous dialogue and flat characterization, the dialectic brought about by the Vertovian juxtaposition of images, the staccato cutting, the interruption of image with text––all of it produces a feeling of dissociation and a desperation to make sense. Even the more didactic elements are ironized by their ambiguity or absurdity (e.g. the dumbshow of the Vietnam war staged for the American sailors in Pierrot le Fou, or the cosplay oration of Saint-Just in Weekend). There is always thinking in Godard’s movies, but the thinking never seems to lead us anywhere. It is a world in which theory itself is in crisis. This was Brecht’s approach––thinking by way of alienation, a mode of thought that capitalism at once engenders and attempts to conceal.

One of the definitions of postmodernity as offered by Jameson is the condition in which art becomes conscious of itself as cultural production, with this consciousness then becoming the content of the product. All of Godard’s work is in a sense an auto-critique, one that is densely aware of itself as part of the engine of manufactured culture. But again, this awareness seems to lead only to self-destruction. As in Joyce, we get a depiction of a culture that understands itself to be in a condition that is perpetually terminal. Things are always coming to an end. There is nothing new under the sun, and we have only the debris of history to make sense of our predicament. Creation happens therefore only through a process of destruction.

Godard himself seemed to reach his own terminus after ‘67, sensing a year-zero was near. Week-end fittingly ends with an absurdist Gotterdammerung, as civilization reverts back to a Hobbesian state of cannibalism and feral eros (reflecting the degraded and cannibalistic state of all culture). The last title card of the film is “fin de cinema”––the end of cinema. The fast-burning, manic energy of Godard’s work during this period seemed to presage the political turmoil that would manifest itself in the paroxysms of ‘68 and beyond. Godard was fond of the quote (sometimes attributed to Lenin) that ethics are the aesthetics of the future. But surely it is the other way around; it is aesthetics that so often point the way to ethics, and it is aesthetic upheavals that first signal the transformation in consciousness that will inevitably find its wider expression in the upheaval of the political and social order.

Perhaps this is why in ‘68, when revolution seemed imminent, Godard temporarily abandoned moviemaking. But by that point, he had already shown that cinema, like literature, could be a restlessly experimental form that could act as a delivery system for philosophical ideas and radical politics, and do so in a way that was accessible and entertaining. Few artists, if they’re lucky, ever achieve this, and even fewer survive. Godard did it in less than a decade, and it is a legacy more than enough for a lifetime.

Jared Marcel Pollen is the author of The Unified Field of Loneliness: Stories (2019) and the novel Venus&Document (2022). His work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Gawker, Jacobin, Tablet, Astra (forthcoming), The Yale Review (forthcoming), and Liberties. He currently lives in Prague. Twitter: @JaredMPollen

[book-strip index="3" style="buy"]