The Politics of Women’s Blues

Hazel V. Carby considers the sexual politics of women's blues and focuses on black women as cultural producers and performers in the 1920s.

The differing interests of women and men in the domestic sphere were clearly articulated by Bessie Smith in the "In the House Blues," a popular song for the mid-twenties which she wrote herself but didn't record until 1931. Although the man gets up and leaves, the woman remains, trapped in the house like a caged animal pacing up and down.

But at the same time Bessie's voice vibrates with tremendous power which implies the eruption that is to come. The woman in the house is only barely restrained from creating havoc; her capacity for violence has been exercised before and resulted in her arrest. The music, which provides an oppositional counterpoint to Bessie's voice, is a parody of the supposed weakness of women. A vibrating cornet contrasts with the words that ultimately cannot be contained and roll out the front door.

The way in which Bessie growls "so weak" contradicts the supposed weakness and helplessness of the woman in the song and grants authority to her thoughts of "murder." The rage of women against male infidelity and desertion is evident in many of the blues. Ma Rainey threatened violence when she sang that she was "gonna catch" her man "with his britches down," in the act of infidelity, in "Black Eye Blues." Exacting revenge against mistreatment also appears as taking another lover, as in "Oh Papa Blues," or taunting a lover who has been thrown out with "I won't worry when you're gone, another brown has got your water on" in "Titanic Man Blues." But Ma Rainey is perhaps best known for the rejection of a lover in "Don't Fish in My Sea," which is also a resolution to give up men altogether. She sang:

The total rejection of men as in this blues and in other songs such as "Trust No Man" stands in direct contrast to the blues that concentrate upon the bewildered, often half-crazed and even paralyzed response of women to male violence.

Sandra Lieb has described the masochism of "Sweet Rough Man," in which a man abuses a helpless and passive woman, and she argues that a distinction must be made between reactions to male violence against women in male- and female-authored blues. "Sweet Rough Man," though recorded by Ma Rainey, was composed by a man and is the most explicit description of sexual brutality in her repertoire. The articulation of the possibility that women could leave a condition of sexual and financial dependency, reject male violence, and end sexual exploitation was embodied in Ma Rainey's recording of "Hustlin' Blues," composed jointly by a man and a woman, which narrates the story of a prostitute who ends her brutal treatment by turning in her pimp to a judge. Ma Rainey sang:

However, Ma Rainey's strongest assertion of female sexual autonomy is a song she composed herself, "Prove It On Me Blues," which isn't technically a blues song but which she sang accompanied by the Tub Jug Washboard Band. "Prove It On Me Blues" was an assertion and an affirmation of lesbianism. Though condemned by society for her sexual preference, the singer wants the whole world to know that she chooses women rather than men. The language of "Prove It On Me Blues'' engages directly in defining issues of sexual preference as a contradictory struggle of social relations.

Both Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith had lesbian relationships and "Prove It On Me Blues" vacillates between the subversive hidden activity of women loving women with a public declaration of lesbianism. The words express a contempt for a society that rejected lesbians. "They say I do it, ain't nobody caught me, They sure got to prove it on me." But at the same time the song is a reclamation of lesbianism as long as the woman publicly names her sexual preference for herself in the repetition oflines about the friends who "must've been women, cause I don't like no men."

But most of the songs that asserted a woman's independence did so in relation to men not women. One of the most joyous is a recording by Ethel Waters in 1925 called "No Man's Mamma Now." It is the celebration of a divorce that ended a marriage defined as a five-year "war." Unlike Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters didn't usually growl, although she could; rather her voice, which is called "sweet-toned," gained authority from its stylistic enunciation and the way in which she almost recited the words. As Waters said, she tried to be "refined" even when she was being her most outrageous.

Waters' sheer exuberance is infectious. The vitality and energy of the performance celebrates the unfettered sexuality of the singer. The self conscious and self-referential lines "I can play and sing the blues" situate the singer at the center of a subversive and liberatory activity. Many of the men who were married to blues singers disapproved of their careers: some felt threatened; others, like Edith Johnson's husband, eventually applied enough pressure to force them to stop singing.

Most, like Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, Ma Rainey and Ida Cox, did not stop singing the blues, but their public presence, their stardom, their overwhelming popularity and their insistence on doing what they wanted caused frequent conflict with the men in their personal lives.

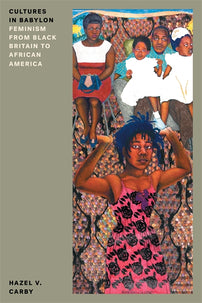

— An edited excerpt from Cultures in Babylon: Feminism from Black Britain to African America by Hazel V. Carby.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]