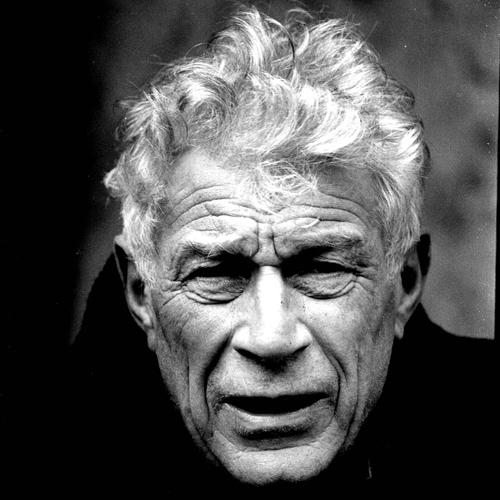

The Portrait of John Berger as Storyteller and Critic—Portraits reviewed

A number of reviews, excerpted below, praise the latest work from one of the world's foremost critics.

The Financial Times focusses on the inseperability of art and politics for Berger, as well as commending Tom Overton, Berger's editor and archivist, for his role in the book:

Read more here.Defining himself as “among other things a Marxist”, Berger trained as an artist but became a writer because “for me, there were too many political urgencies to spend my life painting”. With Ways of Seeing (1972), he revolutionised the reading of art by insisting on social context. Nevertheless, he says, “if I am a political propagandist, I am proud of it. But my heart and eye have remained those of a painter.”

Portraits, a far-ranging selection of writings from across six decades, combines those two sensibilities more seamlessly and authoritatively than any of his previous books. It also, remarkably and exhilaratingly, offers a riposte to some currently powerful ways of thinking about art which have evolved from his own influence.

Many essays here are composites, skilfully stitched together by editor Tom Overton, and their span over decades allows us to watch Berger reconsider, even mellow. But a 2004 extract still laments Bacon’s “very provincial bohemian circle, within which nobody gave a fuck about what was happening elsewhere”. The compelling fact remains that Berger, a vividly engaged critic at the time, missed the significance of the two greatest artists — painter and sculptor — of the postwar generation. It is tribute to his integrity — or stubbornness? — that these failures are showcased, too, in a volume whose breadth and depth bring it close to a definitive self-portrait of one of Britain’s most original thinkers.

Ali Smith, whose speech at a Verso's British Library event in honour of Berger was featured in the New Statesman, focuses on how Berger's own qualities of warmth and compassion suffuse his work as a critic.

I could say that everything I’ve ever written or aspired to write has been in one way or another an appreciation of the work of John Berger. Berger, a force of unselfishness in a culture that encourages solipsism, an insister on open eyes, on the recalibration and re-energising of thinking, feeling, fiercely compassionate, fiercely uncompromising vision in a time that encourages looking away or looking only at the mirror images that create power and make money. Berger, who suggests that the aesthetic act, that art itself, is always collaborative, always in dialogue, or multilogue, a communal act, and one that involves questioning of form and of the given shape of things and forms. Berger, who can do anything with a text, but most of all will make it about the gift of engagement, correspondence – well, I can’t give him anything but love, baby, it’s the only thing I’ve plenty of, and that’s what comes off all his work for me, fervent and warm and vital, an inclusive and procreative energy I can only call love.Read more here.

Portraits is full of references to darkness and light, the unifying properties of light, “the attraction of the eye to light”, but the attraction of the imagination to light, he says, is more complex, “because it involves the mind as a whole . . . vision advances from light to light, like a figure walking on stepping stones”. He quotes Pasolini. “Disperazione senza un po’ di speranza: for we never have despair without some small hope.” And here’s Rosa Luxemburg, via Berger, from that recent letter to the past: “‘To be a human being,’ you say, ‘is the main thing above all else. And that means to be firm and clear and cheerful . . . because howling is the business of the weak. To be a human being means to joyfully toss your entire life in the giant scales of fate if it must be so, and at the same time to rejoice in the brightness of every day and the beauty of every cloud.’

In a world capable of reversing the meanings of “democracy, justice, human rights, terrorism” (“Each word,” he has written, “signifies the opposite of what it was once meant to signify”) we have a writer like Berger, who opens, reveals and reverses the given power relationships so that how we see changes.

Finally, the Scotsman hails Berger's abilities as a great storyteller and investigator, qualities which set him apart as a critic.

Throughout the book, [Berger] brings us insights like this into both the familiar and unfamiliar. His account of the erotic obsessions of Picasso’s late paintings moves from the obvious sad reflection on the impotence of age to offer wider insights into Picasso’s unique place in the art of the 20th century. Berger is terrific too on Rembrandt, Courbet, Daumier and many others. Some of the later artists he writes about are more obscure and occasionally he indulges himself. An essay on Titian, for instance, is a correspondence between himself and his daughter. After his brilliant analysis of the Maya paintings, the Goya essay wanders off into a fragment of a novel and then a short play with Goya, the Duchess and a gardener as the characters. But these are not really aberrations, just a chance to follow the author as he gets up from his desk, perhaps, and starts to daydream. It puts us in his company and as a companion, this is a book to keep nearby.Read more here.

Portraits: John Berger on Artists is available directly from the Verso Website, with a 20% discount and free postage and ebook.