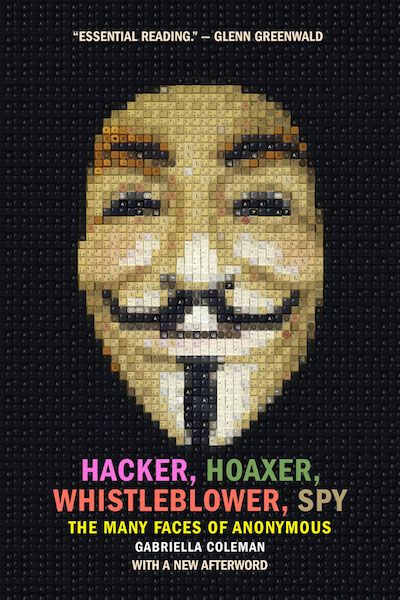

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy awarded the Diana Forsythe Prize—and taken up in a HAU Journal symposium

Established in 1998, the Prize is given annually to the book deemed to best honor the legacy of Diana Forsythe's feminist contribution to the anthropology of work, science, and technology.

The Committee issued the following statement in awarding the prize to Coleman:

Gabriella Coleman’s Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous (Verso, 2014) is a powerful ethnography of the making and remaking of networked computational infrastructures and their animating publics and politics. Taking a multi-method anthropological approach to understanding the unruly online collective known as Anonymous, Coleman creatively continues Diana Forsythe’s legacy of getting underneath the cultural logics motivating projects of computational representation and culture. In her unique ethnographic exploration, she tracks affiliated participants across virtual and physical spaces, providing a rich and highly intricate understanding of the labyrinthine worlds that her hacker-activist subjects occupy.In other Hacker, Hoaxer news: the latest issue of HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory includes a symposium on the book, with contributions from João Biehl and Naomi Zucker, Haidy Geismar, Adam Fish and Luca Follis, and Tom Boellstorff, along with a response from Coleman herself.Writing on a much-criticized and often misunderstood technosocial “movement” lacking a fixed or overarching structure, Coleman’s original book deftly navigates the complexities, ambiguities, and controversies of digital forms of activism. At once intellectually rigorous, impressively thorough, and captivatingly readable,Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy speaks to a wide audience with sophistication and nuance, offering highly generative analysis and eliciting multiple readings that bring us closer to (if never overcoming) the contradictions and uncertainties of her subject matter. Where Anonymous have often been demonized or dismissed in popular media, Coleman refuses the “gross fetish of stereotypes” so often mobilized in its characterization, instead astutely reading Anonymous as a new and important kind of political collective exposing and acting against the security state and its attacks on fundamental freedoms.

Throughout the book, Coleman shifts reflexively between numerous roles: an anthropologist studying sometimes-illegal activity; a participant-observer in an online world; a go-between and translator of sorts between the collective and the public. In the process, she offers a timely and immensely relevant contribution to critical contemporary scholarship and public debates on technology, digital worlds, social movements, and incipient forms of politics.

Expertly probing the social, ethical, and political spheres of democracy and voice in our contemporary world, Coleman’s generous approach opens space to consider the new possibilities for politics, direct action, solidarity, and organizing that are too easily erased or distorted. Enchantment, in her account—that of Anonymous, and her own—presents as an ethical and political possibility, a means of sustaining or cultivating hope, a form that works to propel “disruption and change.” For opening new channels of thought into our technological present and characterizing new forms of politics in-the-making, this brave scholar and her vivid book deserve our highest prize.

In their introduction to the symposium, "The Masked Anthropologist," Biel and Zucker write:

For all of Anonymous’ complexities and contradictions, Coleman’s telling provides rich insight, thorough history, and stimulating analysis. As she exposes the pseudopoliticization that accompanies present-day intelligence and security maneuvers, and draws us into the largely invisible and unstable worlds of digital activism, she also generously offers us her own enchantment while leaving space for multiple possible readings. The optimism of the masked anthropologist resonates with Foucault’s refusal to view his time as a moment of decline or stagnation: “I don’t subscribe to the notion of a decadence,” he writes, “of the sterility of thought, of a gloomy future lacking prospects ... on the contrary, I think there is a plethora” (1998: 325). In opening new channels of thought and characterizing new (if imperfect) forms of politics in-the-making, this brilliant scholar of our technological present rejects deadening futility. In so doing, she allows us to ask how and where such forces emerge—to render politics otherwise, and ourselves a bit freer.Read the whole symposium on the HAU Journal site.