'Francisco de Goya (1746-1828)' by John Berger—from Portraits: John Berger on Artists

On John Berger's 89th birthday and to coincide with the National Gallery's Goya: The Portraits exhibition, we excerpt a chapter on the Spanish artist from his latest book Portraits: John Berger on Artists, edited by Tom Overton.

Portraits: John Berger on Artists is 50% off when you buy through our website, with free shipping worldwide, until Sunday 8th November*. You will also get the ebook, for free, when you buy the print edition! (*excluding North America).

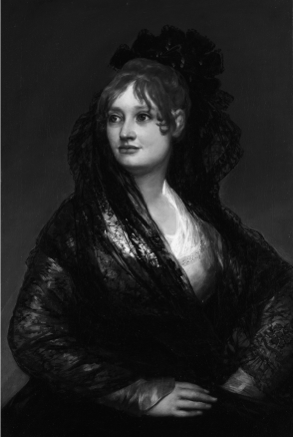

Francisco Goya, Portrait of Doña Isabel de Parcel, 1805

I first met Janos about two years before he began this journal, at the National Gallery. (It is remarkable how, for those who suffer a desire for art, so much does begin and end in it.) We were both standing near the Goya portrait of Doña Isabel when a girl art student strode up to look at it. She had loose dark hair which she flicked back from her face by tossing her head, and she wore a tight black skirt – this was before the fashion for jeans – which looked as though it were held up like a towel and might at any moment come apart but without in the least disconcerting her. She stood in front of the painting, leaning slightly backwards with one hand on her hip, and so echoing quite unconsciously the pose of Doña Isabel herself. I noticed Janos, a tall man in a huge black overcoat, looking at her and then at the painting with considerable amusement. He glanced at me, still smiling. His eyes in their much-creased sockets were very bright. He looked an energetic sixty. I smiled back. When the girl strode off into the next gallery, we both went up to the Goya. ‘The living and the undying,’ he said in a deep, noticeably foreign voice. ‘What a choice!’

Closer to him now, I could study more carefully the expression of his face. It was an urban face, experienced, strained, travelled: but it could still register surprise. It was the opposite of polished. Given the context, it was obvious that he was a painter, and his hands were stained with printing ink; yet in another context one might have guessed that he was a gardener or park-keeper. He was clearly a solitary and had clearly never in his life had a secretary. He had a large nose with hairs coming out of the nostrils; a thick but drawn mouth; a bald brow and top to his head; and a thrusting crooked chin. He stood very upright.

When I inquired what his name was and he told me, I just recognised it. I dimly remembered having seen a book of anti-Nazi war drawings published seven or eight years before. They had struck me because unlike most such drawings they were not expressionist; if, however, I had thought any more about the artist, I had assumed that he had gone back to the Continent. Later, when I used to mention his name to people in the art world, the majority looked blank. He was known to a few isolated groups: to one or two left-wing intellectuals, to a few Berlin émigrés, to the Hungarian Embassy, to a number of young painters whom he had met personally, and – presumably – to MI5.

***

Goya’s genius as a graphic artist was that of a commentator. I do not mean that his work was straightforward reportage, far from it; but that he was much more interested in events than states of mind. Each work appears unique not on account of its style but on account of the incident upon which it comments. At the same time, these incidents lead from one to another so that their effect is culminative – almost like that of film shots.

Indeed, another way of describing Goya’s vision would be to say that it was essentially theatrical. Not in the derogatory sense of the word, but because he was constantly concerned with the way action might be used to epitomise a character or a situation. The way he composed was theatrical. His works always imply an encounter. His figures are not gathered round a natural centre so much as assembled from the wings. And the impact of his work is also dramatic. One doesn’t analyse the processes of vision that lie behind an etching by Goya; one submits to its climax.

Goya’s method of drawing remains an enigma. It is almost impossible to say how he drew: where he began a drawing, what method he had of analysing form, what system he worked out for using tone. His work offers no clues to answer these questions because he was only interested in what he drew. His gifts, technical and imaginative, were prodigious. His control of a brush is comparable to Hokusai’s. His power of visualising his subject was so precise that often scarcely a line is altered between preparatory sketch and finished plate. Every drawing he made is undeniably stamped with his personality. But despite all this, Goya’s drawings are in a sense as impersonal, as automatic, as lacking in temperament as footprints – the whole interest of which lies not in the prints themselves but in what they reveal of the incident that caused them.

What was the nature of Goya’s commentary? For despite the variety of the incidents portrayed, there is a constant underlying theme. His theme was the consequences of Man’s neglect – sometimes mounting to hysterical hatred – of his most precious faculty, Reason. But Reason in the eighteenth-century materialistic sense: Reason as a discipline yielding Pleasure derived from the Senses. In Goya’s work the flesh is a battleground between ignorance, uncontrolled passion, superstition on the one hand and dignity, grace, and pleasure on the other. The unique power of his work is due to the fact that he was so sensuously involved in the terror and horror of the betrayal of Reason.

In all Goya’s works – except perhaps the very earliest – there is a strong sensual and sexual ambivalence. His exposure of physical corruption in his royal portraits is well known. But the implication of corruption is equally there in his portrait of Doña Isabel. His Maja undressed, beautiful as she is, is terrifyingly naked. One admires the delicacy of the flowers embroidered on the stocking of a pretty courtesan in one drawing, and then suddenly, immediately, one foresees in the next the mummer-headed monster that, as a result of the passion aroused by her delicacy, she will bear as a son. A monk undresses in a brothel and Goya draws him, hating him, not in any way because he himself is a puritan, but because he senses that the same impulses that are behind this incident will lead in the Disasters of War to soldiers castrating a peasant and raping his wife. The huge brutal heads he put on hunchback bodies, the animals he dressed up in official robes of office, the way he gave to the cross-hatched tone on a human body the filthy implication of fur, the rage with which he drew witches – all these were protests against the abuse of human possibilities. And what makes Goya’s protests so desperately relevant for us, after Buchenwald and Hiroshima, is that he knew that when corruption goes far enough, when the human possibilities are denied with sufficient ruthlessness, both ravager and victim are made bestial.

Then there is the argument about whether Goya was an objective or subjective artist; whether he was haunted by his own imaginings, or by what he saw of the decadence of the Spanish Court, the ruthlessness of the Inquisition and the horror of the Peninsular War. In fact, this argument is falsely posed. Obviously Goya sometimes used his own conflicts and fears as the starting point for his work, but he did so because he consciously saw himself as being typical of his time. The intention of his work was highly objective and social. His theme was what man was capable of doing to man. Most of his subjects involve action between figures. But even when the figures are single – a girl in prison, an habitual lecher, a beggar who was once ‘somebody’ – the implication, often actually stated in the title, is ‘Look what has been done to them.’

I know that certain other modern writers take a different view. Malraux, for instance, says that Goya’s is ‘the age-old religious accent of useless suffering rediscovered, perhaps for the first time, by a man who believed himself to be indifferent to God’. Then he goes on to say that Goya paints ‘the absurdity of being human’ and is ‘the greatest interpreter of anguish the West has ever known’. The trouble with this view, based on hindsight, is that it induces a feeling of subjection much stronger than that in Goya’s own work: only one more shiver is needed to turn it into a feeling of meaningless defeat. If a prophet of disaster is proved right by later events (and Goya was not only recording the Peninsular War, he was also prophesying) then that prophecy does not increase the disaster; to a very slight extent it lessens it, for it demonstrates that man can foresee consequences, which, after all, is the first step towards controlling causes.

The despair of an artist is often misunderstood. It is never total. It excepts his own work. In his own work, however low his opinion of it may be, there is the hope of reprieve. If there were not, he could never summon up the abnormal energy and concentration needed to create it. And an artist’s work constitutes his relationship with his fellow men. Thus for the spectator the despair expressed by a work can be deceiving. The spectator should always allow his comprehension of that despair to be qualified by his relationship with his fellow men: just as the artist does implicitly by the very act of creation. Malraux, in my opinion – and in this he is typical of a large number of disillusioned intellectuals – does not allow this qualification to take place; or if he does, his attitude to his fellow men is so hopeless that the weight of the despair is in no way lifted.

One of the most interesting confirmations that Goya’s work was outward-facing and objective is his use of light. In his works it is not, as with all those who romantically frighten themselves, the dark that holds horror and terror. It is the light that discloses them. Goya lived and observed through something near enough to total war to know that night is security and that it is the dawn that one fears. The light in his work is merciless for the simple reason that it shows up cruelty. Some of his drawings of the carnage of the Disasters are like film shots of a flare-lit target after a bombing operation; the light floods the gaps in the same way.

Finally and in view of all this one tries to assess Goya. There are artists such as Leonardo or even Delacroix who are more analytically interesting than Goya. Rembrandt was more profoundly compassionate in his understanding. But no artist has ever achieved greater honesty than Goya: honesty in the full sense of the word, meaning facing the facts and preserving one’s ideals. With the most patient craft Goya could etch the appearance of the dead and the tortured, but underneath the print he scrawled impatiently, desperately, angrily, ‘Why?’ ‘Bitter to be present’, ‘This is why you have been born’, ‘What more can be done?’ This is worse’. The inestimable importance of Goya for us now is that his honesty compelled him to face and to judge the issues that still face us.

***

First, she lies there on the couch in her fancy-dress costume: the costume which is the reason for her being called a Maja. Later, in the same pose, and on the same couch, she is naked.

Ever since the paintings were first hung in the Prado at the beginning of this century, people have asked: Who is she? Is she the Duchess of Alba? A few years ago the body of the Duchess of Alba was exhumed and her skeleton measured in the hope that this would prove that it was not she who had posed! But then, if not she, who?

One tends to dismiss the question as part of the trivia of court gossip. But then when one looks at the two paintings there is indeed a mystery implied by them which fascinates. But the question has been wrongly put. It is not a question of who? We shall never know, and if we did we would not be much the wiser. It is a question of why? If we could answer that we might learn a little more about Goya.

My own explanation is that nobody posed for the nude version. Goya constructed the second painting from the first. With the dressed version in front of him, he undressed her in his imagination and put down on the canvas what he imagined. Look at the evidence.

There is the uncanny identity (except for the far leg) of the two poses. This can only have been the result of an idea: ‘Now I will imagine her clothes are not there.’ In actual poses, taken up on different occasions, there would be bound to be greater variation.

More important, there is the drawing of the nude, the way the forms of her body have been visualised. Consider her breasts – so rounded, high, and each pointing outwards. No breasts, when a figure is lying, are shaped quite like that. In the dressed version we find the explanation. Bound and corseted, they assume exactly that shape and, supported, they will retain it even when the figure is lying. Goya has taken off the silk to reveal the skin, but has forgotten to reckon with the form changing.

Goya, The Nude Maja, 1797–1800

Goya, The Nude Maja, 1797–1800

The same is true of her upper arms, especially the near one. In the nude it is grotesquely, if not impossibly, fat – as thick as the thigh just above the knee. Again, in the dressed version we see why. To find the outline of a naked arm Goya has had to guess within the full, pleated shoulders and sleeves of her jacket, and has miscalculated by merely simplifying instead of reassessing the form.

Compared to the dressed version, the far leg in the nude has been slightly turned and brought towards us. If this had not been done, there would have been a space visible between her legs and the whole boat- like form of her body would have been lost. Then, paradoxically, the nude would have looked less like the dressed figure. Yet if the leg were really moved in this way, the position of both hips would change too. And what makes the hips, stomach, and thighs of the nude seem to float in space – so that we cannot be certain at what angle they are to the bed – is that, although the far leg has been shifted, the form of the near hip and thigh has been taken absolutely directly from the clothed body, as though the silk there was a mist that had suddenly lifted.

Indeed the whole near line of her body as it touches the pillows and sheet, from armpit to toe, is as unconvincing in the nude as it is convincing in the first painting. In the first, the pillows and the couch sometimes yield to the form of the body, sometimes press against it: the line where they meet is like a stitched line – the thread disappearing and reappearing. Yet the line in the nude version is like the frayed edge of a cut-out, with none of this ‘give-and-take’ which a figure and its surroundings always establish in reality.

The face of the nude jumps forward from the body, not because it has been changed or painted afterwards (as some writers have suggested), but because it has been seen instead of conjured up. The more one looks at it, the more one realises how extraordinarily vague and insubstantial the naked body is. At first its radiance deceives one into thinking that this is the glow of flesh. But is it not really closer to the light of an apparition? Her face is tangible. Her body is not.

Goya was a supremely gifted draughtsman with great powers of invention. He drew figures and animals in action so swift that clearly he must have drawn them without reference to any model. Like Hokusai, he knew what things looked like almost instinctively. His knowledge of appearances was contained in the very movement of his fingers and wrist as he drew. How then is it possible that the lack of a model for this nude should have made his painting unconvincing and artificial?

The answer, I think, has to be found in his motive for painting the two pictures. It is possible that both paintings were commissioned as a new kind of scandalous trompe l’oeil – in which in the twinkling of an eye a woman’s clothes disappeared. Yet at that stage of his life Goya was not the man to accept commissions on other men’s trivial terms. So if these pictures were commissioned, he must have had his own subjective reasons for complying.

What then was his motive? Was it, as seemed obvious at first, to confess or celebrate a love affair? This would be more credible if we could believe that the nude had really been painted from life. Was it to brag of an affair that had not in fact taken place? This contradicts Goya’s character; his art is unusually free from any form of bravado. I suggest that Goya painted the first version as an informal portrait of a friend (or possibly mistress), but that as he did so he became obsessed by the idea that suddenly, as she lay there in her fancy dress looking at him, she might have no clothes on.

Why ‘obsessed’ by this? Men are always undressing women with their eyes as a quite casual form of make-believe. Could it be that Goya was obsessed because he was afraid of his own sexuality?

There is a constant undercurrent in Goya which connects sex with violence. The witches are born of this. And so, partly, are his protests against the horrors of war. It is generally assumed that he protested because of what he witnessed in the hell of the Peninsular War. This is true. In all conscience he identified himself with the victims. But with despair and horror he also recognised a potential self in the torturers.

The same undercurrent blazes as ruthless pride in the eyes of the women he finds attractive. Across the full, loose mouths of dozens of faces, including his own, it flickers as a taunting provocation. It is there in the charged disgust with which he paints men naked, always equating their nakedness with bestiality – as with the madmen in the madhouse, the Indians practising cannibalism, the priests awhoring. It is present in the so-called Black paintings which record orgies of violence. But most persistently it is evident in the way he painted all flesh.

It is difficult to describe this in words, yet it is what makes nearly every Goya portrait unmistakably his. The flesh has an expression of its own – as features do in portraits by other painters. The expression varies according to the sitter, but it is always a variation on the same demand: the demand for flesh as food for an appetite. Nor is that a rhetorical metaphor. It is almost literally true. Sometimes the flesh has a bloom on it like fruit. Sometimes it is flushed and hungry-looking, ready to devour. Usually – and this is the fulcrum of his intense psychological insight – it suggests both simultaneously: the devourer and the to-be-devoured. All Goya’s monstrous fears are summed up in this. His most horrific vision is of Satan eating the bodies of men.

One can even recognise the same agony in the apparently mundane painting of the butcher’s table. I know of no other still life in the world which so emphasises that a piece of meat was recently living, sentient flesh, which so combines the emotive with the literal meaning of the word ‘butchery’. The terror of this picture, painted by a man who has enjoyed meat all his life, is that it is not a still life.

If I am right in this, if Goya painted the nude Maja because he was haunted by the fact that he imagined her naked – that is to say imagined her flesh with all its provocation – we can begin to explain why the painting is so artificial. He painted it to exorcise a ghost. Like the bats, dogs, and witches, she is another of the monsters released by ‘the sleep of reason’, but, unlike them, she is beautiful because desirable. Yet to exorcise her as a ghost, to call her by her proper name, he had to identify her as closely as possible with the painting of her dressed. He was not painting a nude. He was painting the apparition of a nude within a dressed woman. This is why he was tied so faithfully to the dressed version and why his usual powers of invention were so unusually inhibited.

I am not suggesting that Goya intended us to interpret the two paintings in this way. He expected them to be taken at their face value: the woman dressed and the woman undressed. What I am suggesting is that the second, nude version was probably an invention and that perhaps Goya became imaginatively and emotionally involved in its ‘pretence’ because he was trying to exorcise his own desires.

Why do these two paintings seem surprisingly modern? We assumed that the painter and model were lovers when we took it for granted that she agreed to pose for the two pictures. But their power, as we now see it, depends upon there being so little development between them. The difference is only that she is undressed. This should change everything, but in fact it only changes our way of looking at her. She herself has the same expression, the same pose, the same distance. All the great nudes of the past offer invitations to share their golden age; they are naked in order to seduce and transform us. The Maja is naked but indifferent. It is as though she is not aware of being seen – as though we were peeping at her secretly through a keyhole. Or rather, more accurately, as though she did not know that her clothes had become ‘invisible’.

In this, as in much else, Goya was prophetic. He was the first artist to paint the nude as a stranger: to separate sex from intimacy: to substitute an aesthetic of sex for an energy of sex. It is in the nature of energy to break bounds: and it is the function of aesthetics to construct them. Goya, as I have suggested, may have had his own reason for fearing energy. In the second half of the twentieth century the aestheticism of sex helps to keep a consumer society stimulated, competitive, and dissatisfied.

Goya, The Clothed Maja, 1800–05

***

In each corner of the ceiling there are cobwebs. In an hour Alec will give the violets back to Jackie, in an hour he will get to hell out of here. He doesn’t really believe in the ten bob. It seems to him that if Office Day is ever to begin again, Corker and he will have to pretend that the day Corker kissed the floor never happened. And if they pretend it never happened, then Alec was never offered his rise. He goes across to the cracked draining board where the old brown teapot is always left to drain upside down. There he begins another line of reasoning for not believing in the ten bob. It begins: I can’t help being sorry for the Poor Bugger. He pours the hot water into the pot to warm it. He is sorry for Corker because since lunchtime Corker has grown old and incapable. He imagines Corker in his dressing-gown tomorrow morning making his breakfast here – Alec himself is now putting two teaspoonfuls of tea into the pot – and the poor bugger won’t get much of a breakfast. But more than anything else, he is sorry for Corker because of all that remains unfore- seeable, unknown, unsaid. Alec isn’t certain why Corker left his sister in such a hurry, or why she is dying, or why Corker said Fucking Heavy, or why he keeps a loaded revolver in his drawer, or why he says he’ll have Bandy Brandy for a housekeeper, or why he is behaving like a drunk upstairs, but he is certain that Corker couldn’t explain why either. Corker, it seems to Alec, is being hustled along as though there was a 100-m.p.h. gale behind him. It’s a man-made gale that has got into a tunnel and Corker is being hustled through the catacombs. The kettle, boiling, whistles. Alec has never seen a catacomb but, as he pours from the kettle he can feel and hear the crusts of fur that have formed over the years inside (they weigh one side of the kettle down and they make a brittle tinkling noise) and these suggest to him the fleshless, encrusted, mineral and subterranean world which he uses as a metaphor to describe to himself what he imagines to be the nature of Corker’s suffering. He goes across to the cupboard. On one shelf a few odd cups and saucers and plates. On another shelf a packet of salt, some tea, a roll of biscuits and a small, almost empty pot of Marmite. On the lowest shelf are the sheets and pillow cases which Corker mentioned. Alec leaves the cups on the Marmite shelf and bends down to examine the sheets. If Corker explains nothing, Alec can search for himself. The sheets don’t look new. Presumably Corker smuggled them out of West Winds. Did he also have a double-bed there? Behind the sheets he can now see two boxes. One is a white cardboard box with nothing written on it. He opens it. Inside is a bottle, about the size of a gin bottle. It is unopened. The label is in a foreign language but Alec reads the word Kummel and recognises it as the kind of booze Corker was talking about in Vienna. The second box is golden coloured and has Allure written over it in an embossed, black and sloping script. Alec carefully sees whether this one will open too. It will. Inside is a tray of chocolates of different shapes and in different deep-coloured silver-papers. A few of the chocolates have been eaten and their deep-coloured cups left. Above the tray, resting against the inside of the lid, is a picture, like a gigantic cigarette card. It shows a woman lying naked on her back on a bed. She has dark hair and big eyes but no hair between her legs so that she must have been shaved. She is small and about the same size as Jackie. Her skin is very white – even the underneaths of her feet are white. It looks like a photograph but it is coloured and might be a painting. Underneath is written Maja Undressed. Alec looks down again at the chocolates and pointlessly starts counting how many have been eaten. Seven. He pictures Corker eating them in bed. Then he pictures him looking at the woman whilst he eats them. Help! he thinks, and shuts the box and puts them both back behind the folded sheets which are glossy with ironing. He takes the two cups to the table beside the gas stove. The milk is always kept in the wooden cupboard underneath the sink to keep it cool. On the windowsill above the sink are the violets. The lead waste-pipe U-bends through the cupboard. The difference between the milk that goes into the bottle and the waste water that goes through the pipe suggests to him the different histories of his penis and Corker’s. He sighs and kicks the door shut with his foot. He renotices the violets and retraces their history. He asks himself why Corker can’t be like other men, like other men but just older than some. He remembers Corker the baby on the blue cushion. He remembers Corker saying that Kummel is quite strong. It crosses his mind that he might open the bottle and put some in Corker’s tea. As he gives him the cup, he will say: with love from Maja. Then the old man might fall asleep in a drunken stupor, muttering Maja! Maja! My love! The fucker, thinks Alec, the drunken fucker who knelt down on his knees to lick the floor. Alec pours the milk into the two cups. One is slightly cracked. He has jumbo-size vegetable dishes but no decent cups. When Alec pours the tea on top of the milk and it goes the familiar ginger-brown, he remembers Jackie making tea for breakfast this morning. Tea, tea, tea, tea, he thinks, and each tea represents somebody wanting a gingerbrown cupful, himself drinking tea in Jackie’s mother’s kitchen, his own mother, his brothers taking their tea cans to work, the cycling club when it’s raining and stopping at a caff, the boys hanging around the tea stall by the station at two in the morning. It is true that corker also likes tea but Corker is different. Corker with his chocolate-box and round tables and fancy sentiments, and these all get dragged in when he drinks a cup and Alec has to sit there listening. Alec can’t blame him for what he was born like. But he now sees the conclusion of the second line of reasoning for not believing in the ten bob: I can’t help being sorry for the poor bugger but I can’t stay with him for ever, well, can I?

***

ACT 1, SCENE 4

day. spring (1794). Duchess’s residence. To right of chapel a bed with muslin hangings. DUCHESS bent over bed murmuring. GARDENER painting wheel of carriage. GOYA opens carriage door, climbs down. GARDENER stops painting. Both men watch DUCHESS, who continues her ministrations to sick child in bed.

DUCHESS: Going away, going away, soon there’ll be no pain left, I’ll take it all away. Don’t fret, give it to me, little one . . .

GARDENER: If she had a child of her own – the Duke, they say, is not a breeding animal.

DUCHESS: Sip, darling, from the lemons of our very own garden.

GOYA: Nobody on earth should be allowed to have a voice like hers.

DUCHESS: Did you dream the world was bad? No, no, only theirs, not ours. It’s cooling – if I press it against you – see – it cools, it cools my honey.

GOYA: It’s so beautiful, it cuts your throat from ear to ear, a voice like hers.

DUCHESS: There, the hurt is coming, come to me, come to me, we’ll mend everything, feather by feather . . . come, little pain, come to Cayetana, come, little death.

GOYA: My mother used to say death was a feather.

GARDENER: Your mother, Don Francisco, is a woman who weighs her words.

DUCHESS: Don’t come too close, both of you. Not too close. His eyes are closed.

GARDENER: The swallowing disease? DUCHESS: Peace.

GOYA: Scarlet fever?

GARDENER: The illness of the marshes? GOYA: Typhoid?

[DWARF leaps up, tears down hangings and jumps out of bed.] DWARF: Growing pains!

[GOYA, seized with a fit of rage, swears at the GARDENER.] DUCHESS: Why are you so angry? Come and sit beside me. Let us say good day to each other. Good day, Frogman.

GOYA: How does your husband put up with that creature?

DUCHESS: My husband puts up with nothing. He plays Haydn.

GOYA: And I put up with everything.

DUCHESS: Don’t you think others have the right to play jokes? Does every caprice have to be signed by the master on a plate?

GARDENER: My God! Do you hear what she says! You’ve shown her, haven’t you? You’ve shown her. How many times have I told you to show nobody? It’s dangerous for nineteen reasons.

DUCHESS: Baturros! Baturros! You don’t know how to live. Neither of you even knows the difference between a coachman and master. Listen how he talks to you.

GOYA: (To GARDENER) She has only seen one or two donkeys.

GARDENER: And the donkey is who? Twenty reasons. Have you ever heard anybody stop talking here? Never. Prattle! The Devil needs nothing more.

DUCHESS: And in Aragon, sir?

GARDENER: In Aragon, Your Duchess, men measure their words, use them sparingly and keep them.

[GOYA makes friendly sign to GARDENER, who returns to the carriage, picks up a paint pot, gets in, shuts door.]

DUCHESS: Are you still angry? I have arranged something special for you.

GOYA: More theatre with the Dwarf? DUCHESS: Do you know why I call him Amore? GOYA: I killed a man once.

DUCHESS: I’ve never met a man who hasn’t boasted of killing another. Even my husband says he killed a man . . . a flautist it seems. No more need for anger. I want to show you something.

[GARDENER pulls down blind of carriage window. DUCHESS enters the ruined chapel, followed by GOYA. Silence. We do not see the painting they are looking at.]

DUCHESS: I acquired it at the age of thirteen when I got married.

GOYA: He was impervious. He judged nothing. He kept his eternal distance. Only his glance caresses her.

DUCHESS: His glance! What does his glance matter? There’s a woman there, lying on a bed, naked. I watch her every night after my prayers. It’s she who counts.

GOYA: For very little, she counts for very little. Look at the draperies which echo and enclose her body. He knew exactly what he was doing.

DUCHESS: She counts for very little! Your impudence! You peer at us, you get a cunning kick out of pinning us with your brushes to your sheets, your canvases, and then you boast: He knew exactly what he was doing! You know nothing. Men see only surfaces, only appearances. Incorrigibly stiff, incorrigibly rigid, the lot of you! Male monuments to your everlasting erections!

GOYA: I could do better.

DUCHESS: How would you paint me?

GOYA: Lying on your back, legs crossed. Your eyes looking into mine.

DUCHESS: Dressed?

GOYA: For those who wish.

DUCHESS: Undressed! Coward!

GOYA: First dressed!

DUCHESS: What patience! What restraint.

GOYA: Next, in the twinkling of an eye, undressed.

DUCHESS: With my consent.

GOYA: With your consent, Cayetana, or without it. I can tear off your clothes. I can strip you as well as I can paint you. Here! (He points to his head.) That’s where I have an edge over Velázquez. No mirrors. I advance on my stomach. Mix my colours with spunk.

DUCHESS: Your colours, sir, are your business. It will be done from memory. You will paint me when you are alone. You will remember all the women you have known, all the women you have stripped – as you so eloquently put it – you will close your eyes and see them again and then you will use all your effort, all your virility, all your speed to recall what distinguishes every square centimetre of the body of the Thirteenth Duchess of Alba from the body of any other woman now or hereafter. From memory. It will be a solitary proof of your love . . . Afterwards I promise you a month in the country . . . the two of us together.

[GARDENER climbs out of carriage, starts painting wheel. GOYA crosses stage.]

GOYA: More and more and more and more . . . brazen! [GOYA enters carriage. DUCHESS waves a handkerchief.]

DUCHESS: Work fast, Frogman. [Lights fade]

ACT 2, SCENE 8

Night (1811). The same as previous scene except that the line on which prints are pegged now crosses the whole room. GOYA is fingering the prints on the line. GARDENER is splitting wood with an axe for the fire.

GARDENER: I brought in the barosma plants this morning. I’ve never known such cold so early. I was a bit frightened for them.

GOYA: Frightened for what?

GARDENER: The barosma plants.

GOYA: In God’s name what are they?

GARDENER: The little bushes in the pots with white flowers. The ones in the courtyard.

GOYA: White, did you say? [GARDENER nods.]

Blind! All of you. You’re blind! The flowers you’re frightened for are pink. Not white. White, if you must, but stained with blood. Stop! Don’t move your arms. Keep the axe there, Juan.

[GARDENER, with axe raised above his head, freezes. GOYA continues to examine prints.]

GARDENER: If you need a drawing, Don Francisco, better do it quickly.

GOYA: Keep the axe there! Drawing! Drawings come by them- selves. You just untie the sack, lift it up, tip it, and out pours the debris. Drawings are debris. Don’t move, Juan.

GARDENER: I have to now.

GOYA: I thought you were strong. I thought you had the shoulders of a bull.

GARDENER: There’s a louse in my armpit. GOYA: Don’t move. Which one? I’ll find it for you. GARDENER: The left.

[GOYA pulls up GARDENER’S shirt, searches, spectacles on the end of his nose.]

GOYA: Can see nothing! Need a candle.

GARDENER: [Starting to laugh] It’s tickling.

[GOYA steps back. GARDENER lowers axe and splits wood.] GOYA: I wanted to give the log at your feet a little more time.

GARDENER: In the circumstances a double cruelty.

[GOYA doesn’t understand. GARDENER takes paper from table and

writes on it: DOUBLE CRUELTY.]

GOYA: If logs could see, if they had eyes, if they could count minutes, it would be better for the axe to descend immediately. But logs can’t count.

GARDENER: You’ve never heard what they call men in Malaga? GOYA: Men?

GARDENER: They call a man a log with nine holes!

[GOYA counts the holes.]

GOYA: Did you find any rice today?

GARDENER: No. The French took everything before leaving, and what they didn’t take the British have pillaged. Either that or people don’t want to sell to us any more. They look dangerous when I ask. In my opinion, Don Francisco, we should prepare to go into hiding. Only the illness of Doña Josefa has prevented me saying this before. I know a place where we can go.

[GOYA appears not to have heard. GARDENER writes on paper: HIDING?]

GOYA: There’s not the slightest cause for alarm. I’ve already offered my services to the victors. Conquerors need painters and sculptors. Never forget that. Victory is ephemeral – as ephemeral as played music. Victory pictures are like wedding pictures, except there’s no bride present. The bride is their own triumph. I don’t know why, but it has always been so throughout history. So they want mother-fucking portraits of themselves with their invisible bride. And I can do these portraits like no one else can. I have a weakness for victors – above all for their collars, their boots, their victory robes. I think we were all meant to be triumphant. Before there was any destiny, we were children of a triumph. We were all born of an ejaculation.

[Enter DOCTOR.]

DOCTOR: Your wife is asking to see you. I have one thing more to say to my husband, she says. [Exit DOCTOR hurriedly.]

GOYA: Soon I’ll do the Duke of Wellington. He insists upon a horse.

GARDENER: Don Federico has already gone into hiding.

GOYA: When the Whore’s Desired One returns to sit on our throne, I shall paint him with a sword under his hand and a cocked hat under his arm. And if he won’t sit for me, I’ll paint him from memory. (Looks in mirror.) Everyone will forgive me.

GARDENER: The washerwomen say you’re not so deaf you don’t hear the clink of reales in the money bags. That’s how you know when to change sides, they say.

GOYA: Everyone will forgive me. [Enter DOCTOR.]

DOCTOR: I regret to have to tell you, Don Francisco, it’s too late. Your wife is dead.

[GOYA falls to his knees.]

GOYA: Even my wife will forgive me.

[GOYA remains kneeling with bowed head. Imperceptible sound of the sea. Abruptly he scrambles to his feet.]

If only men didn’t forgive!

[GOYA grasps the clothes line with both hands and walks beside it, holding on like a man in a gale.]

Do you know how much is unforgiveable? Do you know there are acts

which can never be forgiven? Nobody sees them. Not even God.

[Sea becomes louder.]

The perpetrators bury what they do from themselves and others with words. They call their victims names, they fasten labels to them, they repeat stories. Everything is prepared by curses and insults and whispering and speeches and chatter. The Devil works with words. He has no need of anything else. He distributes words with innocent working of the tongue and the roof of the mouth and the vocal chords, people talk themselves into evil, and afterwards with the same words and the same wicked numbers they hide what they’ve done, so it’s forgotten, and what is forgotten is forgiven.

[GOYA comes to a print.]

What is engraved doesn’t forgive.

[GOYA falls to his knees.]

Do not forgive us, O Lord. Let us see the unforgivable so we may never forget it.

[GOYA somehow gets to his feet, walks to exit where DOCTOR entered.]

Forgive me, Josefa, forgive me . . .

ACT 3

Early spring morning (1827/8). Sunshine. The garden of Goya’s house in Bordeaux. (The scene is almost identical with that of the cemetery.) GARDENER on ladder is pruning a vine against a wall. Enter GOYA (now over eighty) with stick, accompanied by FEDERICO (same age).

GOYA: (Pointing) There’s a Goldfinch, there in the almond tree – do you see him?

FEDERICO: I tell you every morning, Francisco, me eyes are failing. [The two old men stand still. GOYA imitates song of Goldfinch.]

GOYA: That’s how he sings, Goldfinch.

FEDERICO: Your new painting?

GOYA: Two centuries ago in Amsterdam a Dutchman painted Goldfinch.

FEDERICO: (Shouting) How’s the new painting?

GOYA: Sky’s wrong behind the head. Never had trouble with a sky before.

FEDERICO: French skies are not the same. Look at it. Milky. French bakeries are different too. With age, I regret to say, I find myself from time to time becoming greedy.

[FEDERICO takes a brioche out of his pocket, offers half to GOYA. They sit.]

GOYA: Have you said yet: ‘With age, I regret to say, I find myself from time to time becoming greedy’?

[FEDERICO throws crumbs to the birds.]

I slept better this night. No dreams. That’s why you arrived before I was up.

FEDERICO: Didn’t matter. I had plenty to think about . . . there are spies from the Holy Office sent here to Bordeaux. I’m sure of it. Don Tiburcio has refused to give us any more money for the paper.

GOYA: Which one?

FEDERICO: Our paper in Spanish – the one I edit. GOYA: I’ll do a lithograph for you.

FEDERICO: The only explanation is that they threatened to maltreat Don Tiburcio’s family in Valencia. Meanwhile we owe three hundred to the printer.

GOYA: Soon there’ll be more exile papers in the world than stars in the sky.

FEDERICO: Just three hundred to pay the printer.

GOYA: My lithographs aren’t selling. People don’t want to know. They want everything in colour and stereo . . . What’s the latest news from our country?

FEDERICO: The latest! The dark ages. The Constitution annulled and void. Thought manacled. People disappearing in the streets. Torture. Electric shocks. Underground garages. The gluttony of terror. The same as I tell you every morning, my friend. Will anybody ever bring news of a different sort? The latest, Paco, is that we’re already living in the future. Not the one we fought and died for. The one the giants substituted for ours . . . That’s the latest. Will it ever be different?

GOYA: If you’re quiet for a moment, I’ll do Nightingale.

FEDERICO: If I didn’t know better, Frogman, I’d say you’d gone simple.

GOYA: Then don’t ask simple questions like: ‘Will anybody ever bring news of a different sort?’

FEDERICO: So you heard me?

GOYA: Of course not.

FEDERICO: Everywhere the restoration of the past. Everywhere boasts about what was once thought shameful. (Shouting) Tell me what’s left of our hopes.

GOYA: This! (Imitates Goldfinch.) What’s left of our hopes is a long despair which will engender new hopes. Many, many hopes . . . I’m going to live to be as old as Titian.

[Enter PEPA.]

PEPA: Your hot chocolate is waiting in the house.

FEDERICO: Everything should be clear, except hot chocolate which should be thick.

GOYA: Has he said it again?

[PEPA nods and takes GOYA’s arm. Exit FEDERICO and GARDENER, carrying ladder, towards house. PEPA and GOYA walk slowly towards swing. They speak softly, almost whispering. GOYA has no difficulty in hearing.]

Have you read the pages I marked of Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas?

PEPA: All of them.

GOYA: And?

PEPA: They were about the Last Judgement.

GOYA: And the story about me?

PEPA: The painter Hieronymus Bosch finds himself in hell and there he’s cross-questioned. When you were a painter on the earth,

they ask him, why did you paint so many deformed men? And Hieronymus replies to them: Because I don’t believe in Devils.

GOYA: Correct.

[PEPA sits on a swing. GOYA stands before her.]

Do you know who is the favourite in the asylum down by the river? Napoleon! I counted fifteen men wearing hats, and on the hats scraps of paper with the words ‘I am Napoleon’ written on them. Do you know why Napoleon appeals to the mad?

PEPA: No.

GOYA: Because Napoleon was mad enough to boast, ‘I have an annual income of three hundred thousand men!’

[PEPA picks off some flowers, offers them to GOYA.]

PEPA: On Friday at 2 p.m. in the Place d’Aquitaine, there will be a public execution, with the guillotine, French style.

GOYA: I shall be there.

PEPA: A poor wretch called Jean Bertain who murdered his brother-in-law.

GOYA: Perhaps the brother-in-law was raping his niece. Amongst men pity is rare.

PEPA: When you feel pity, you close your eyes.

GOYA: I have eyes in the back of my head. They never close. Do you love me a little?

PEPA: A little, a lot, passionately?

GOYA: If I painted a miniature on ivory it could hang between your breasts. Am I mad, Pepa?

[GOYA sits on a stool, takes his head in his hands.]

A man bends double between a pair of lips. He tries to get into the mouth. When he is in, it’s very difficult for him to get out. One must name everything one sees for what it is. Never stop looking at consequences. The only chance against barbarism. To see consequences.

PEPA: Don’t torture yourself, Francisco. It happens at the end of the morning – it passes, it goes away. Let’s play together. In our family album (Opens a book on her knees) I put a picture of a young man. He’s wearing a large black hat and he has dark piercing eyes.

GOYA: Doubtless he was very ambitious.

PEPA: Large, sensuous mouth. Strong appetites.

GOYA: In our family album I put a picture of a man standing before an easel.

PEPA: Around the brim of his hat there are candles.

GOYA: He worked all night.

PEPA: Quel panache! He has very smart, tight trousers. And now the same man, older. He’s wearing glasses.

GOYA: He’d seen too much.

PEPA: He has a good complexion and he has a white silk scarf round his neck.

GOYA: It was already the year of the French Revolution.

PEPA: In our family album I put a picture of a man standing against a blackness. He looks stunned – stunned by the fact he’s still alive.

GOYA: He’s simply old – almost seventy. Madrid is infected by the plague and it has killed Amore.

PEPA: The expression changes but it’s always the same man. GOYA: It’s perhaps the same man. But it’s not me.

PEPA: Yes, it’s you and it’s your art, you painted the pictures.

[Suddenly GOYA loses interest. He is staring hard at the Duchess of Alba’s grave beyond the swing. The DUCHESS appears. PEPA cannot see her.]

GOYA: Leave me now, Pepa.

PEPA: Your art, Don Francisco.

GOYA: Go to hell with my art!

PEPA: You were a prophet. In your art you foresaw the future.

[DUCHESS advances towards GOYA.] GOYA: Come, come.

PEPA: With such compassion . . . GOYA: Get out, I tell you, fuck off.

[GOYA chases PEPA out of the garden with his stick. He turns to the audience.]

Voyeurs! Fuck off!

[His back to the audience, he watches DUCHESS undress for him, as in a striptease.]

My darling life.

[DUCHESS opens her arms to him.]

DUCHESS: Everything is for you, every feather. Come, my love, come, come, my frogman.

[DUCHESS disappears. GOYA falls in a heap onto the ground. The stage is silent. As if the curtain should now come down but the mechanism doesn’t work. PEPA enters, sits on the ground, places GOYA’s head on her lap.]

PEPA: Every time you do the same thing. She always escapes from you. You’re never quick enough.

GOYA: I walk on sticks . . .

Goya, Will She Live Again, 1810–20

[Enter from different directions all other actors, dressed as they were in the Prologue. GARDENER, masked, goes over to beehive. PEPA gently disengages herself from GOYA, gets to her feet and rings the bell. The actors begin to leave the cemetery exactly as in the Prologue. PEPA rejoins GOYA.]

WIDOW: (To herself) Let a little justice come to this earth, dear Lord.

DOCTOR: (To ACTRESS) You wanted to seduce your father so you became an actress.

GOYA: (To PEPA) Have they finished? Is my portrait done? PEPA: Yes, it’s done.

GOYA: They must sign it.

PEPA: It’s done.

GOYA: Am I dead, Pepa?

PEPA: Don’t worry. For tonight, you’re well and truly dead.

[LEANDRO is the last to leave.]

LEANDRO: (Shouting to PEPA) Wear your new white dress! GOYA: That’s good . . .

[GOYA closes his eyes and sleeps. GARDENER blows smoke into hive. White curtain, without image or signature, descends.]