Not Us, Me

Since Donald Trump’s electoral defeat of Hillary Clinton for President of the United States, liberal commentary has fixated on the problem of identity politics. Like the incessant tonguing of a sore tooth, this fixation locates a problem but doesn’t address it. It doesn’t even analyze it. It tells us nothing about the appeal of identity, attachments to it, investments in it. At best, liberal commentary (such as has appeared in the New York Times) repeats conservative criticisms of political correctness, glossing them with erudite condescension.

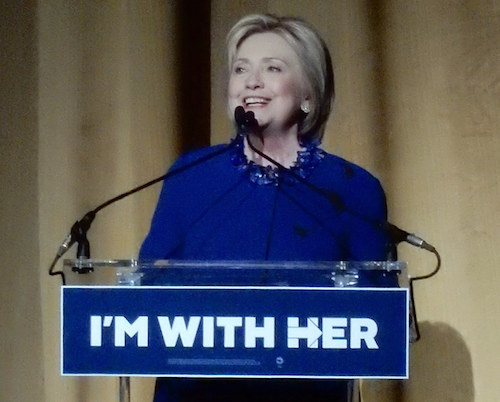

Clinton’s most prominent campaign slogan was “I’m with Her.” The “I” in the slogan is the voter. The “Her” is Clinton. The slogan is the voter’s statement that they are voting not specifically for Clinton but for a woman. The voter is the kind of person to whom gender matters, whose vote is one that is first and foremost a vote for gender justice — it’s her turn. Men have been president; it’s time for a woman. The slogan tells us something about what the voter values, about who the voter is as a person. About the candidate the slogan tells us only her gender. The candidate’s gender is what is most distinctive, most politically salient, about her.

This slogan that tells us about the voter, not the candidate likely made sense to the Clinton campaign because the slogan inhabits so easily the affective networks of communicative capitalism. Communicative capitalism names the merging of democracy and capitalism in mass personalized media, the networks of mobile phones, wifi, social media, and mass distraction through which we circulate our feelings and opinions in ways that make us feel important, engaged, political. Communicative capitalism enjoins the cultivation of individual identity. We are told, repeatedly, that we are unique and special, that no one can speak for us, that we have to do it all ourselves. Clinton’s slogan doesn’t speak for voters. It’s a registration of the voter speaking for themselves, a hashtag-ready statement of identity.

The injunction to assert one’s individual identity is unceasing in communicative capitalism. Taking care of oneself now appears as a politically significant act, rather than as a symptom of the dismantled social welfare net and obscenely competitive labor market wherein we have no choice but to care for ourselves if we are going to keep up. Clinton’s slogan is the neoliberal extension of second wave feminism’s insight that “the personal is political.” Because the personal is political, the political question is about me, what does my vote say about me?

Against this individualist backdrop, the votes of others are also about me. The post-election anguish circulating among Clinton voters on social media, and repeated in those mainstream outlets that consider reporting on social media to be journalism, is deeply personal. People express their own individual fears and their fears for their children. They report deep anxiety and panic. Some extend this anxiety and panic such that they consider everyone who voted for Trump (or even everyone who did not vote for Clinton) to be racist, sexist, and homophobic. These extensions are not accounts of the structures of US society. They are projections of attitudes onto others, ways of imagining others as enemies and rivals. The votes (or non-votes) of all these others are really about the projector (the voter “with her”). Before the election, the one “with her” was safe. Now they are at risk.

In the affective networks of communicative capitalism, facts about the prevalence of raced violence and deportations under Obama, class differences within racial categories, and demographics of non-voters and Trump voters have little registration. With regard to circulatory power, truth and lies, fact and fiction, are indiscriminate. Social media relies on intense statements of personal feeling. It thrives on the circulation of affect. Outrage gets more shares and likes than nuance. Righteousness registers as #courage. When our already fragile, conflicted, and never fully coherent identities are at stake, which is always (unless we are sharing cat photos), disagreement feels like bullying.

During the 2016 election, identity politics blended into communicative capitalism’s commanded individuality. Demographic categories used by pollsters took on a fixity, a capacity to determine the views and preferences of all belonging to the category. The complex array of factors that figure into political choices, the myriad ways such choices are not determined by an essence designated by and captured within demographic terms, the fact that political identities have to be constructed rather than assumed; all this was submerged under an ever-amplified insistence on a direct connection between identity categories and political commitment. The blend of identity politics and commanded individuality was a hallmark of the Clinton campaign, from its opportunistic tweets on intersectionality, to its misrepresentations of Bernie Sanders, to its excoriation of left critics in personal terms — childish, purist, naïve, irresponsible. For the most part, the cries and accusations were unmoored from policies, as disconnected from attention to the people who would benefit from free college tuition and single-payer health insurance as they were from those who politics exceeded the identitarian limits set by the Clinton’s camp. They circulated as mood, as the election’s affective condition of attachment to voters in their individual specificity — as long as that specificity corresponded to expectations of sexed, gendered, and raced identity.

As I detail in Crowds and Party, recent work by sociologists Jennifer Silva and Carrie Lane sets out the material conditions that have given rise to the intense attachment to individual identity. Mistrusting institutions, many people today believe that they can only rely on themselves. Their sense of dignity and self-worth comes from being self-sufficient. Skeptical of experts, they speak from their own experience, drawing legitimacy from the identity that makes them who they are. The more they have to combat, to overcome, the more valuable their identity. Solidarity feels like a demand to sacrifice one’s own best thing, yet again, and for nothing.

Identity politics weaponizes the feeling that one has to hold on to what is in them more than themselves. It highlights one specific feature out of a given set of demographic features, turning this feature from a base to be defended into a launcher for new attacks. Weaponized identity politics lets me insist that this time I will not be sacrificed, I will survive. Even more, it helps assuage some of the guilt of the privileged — they are on the correct side of history, for once. The added bonus of this weaponized identity politics is how the privileged can use it against each other even as they leave communicative capitalism’s basic structure intact. We see this when we look at the arsenal of identities — sex, race, gender, sexuality, ability, ethnicity, religion, citizenship — and recognize what is missing: class.

The identities from which one can speak rely on the exclusion of class. On the one hand, the assumption is that class means white. Yet prevalent within the discourse of identity politics are accounts of the racialization of poverty, the feminization of work, important accounts that recognize and analyze the fact that class in the contemporary United States does not mean or signify white at all. What, then, is behind the attachment to identity that not only refuses to consider the impact of economic inequality on the election but that responds to any discussion of economics as if it were premised on an underlying racism?

The answer is capitalism. The identity politics that manifest during the election is premised on the continuation of capitalism, not its overturning. It is a liberal identity politics at odds with the long history of communist and socialist anti-racist, anti-sexist, and anti-colonialist struggle. Suppressing the history and present of radical black anti-capitalist struggle, of communist feminism, of the leading role of people of color in working class movements, the politics of identity functioned in the 2016 election to demolish rather than build solidarity. The missing subtext of the Democratic Party’s embrace of diversity was that its was a diversity of the successful, of the winners, of the multicultural celebrities and photogenic talented tenth who appear as so many talking heads on MSNBC. The Democratic substitution of entrepreneurs for workers under the guise of racial inclusion is class war, a war that leaves in its wake disproportionate numbers of black and brown bodies. White-washing the working class legitimizes policies that diminish the lives and futures of millions of working class people of color.

A non-white colleague recently said to me that he didn’t mind being called an elitist. Trump voters were the racist white working-class and he had no desire to reach them, be in coalition with them, or anything. A reductive, individualist, affective approach to the election let him embrace a class position he might otherwise reject (at least publicly). Multiculturalism is the form his defense of capitalism takes.

The investment in identity is intense. It shores up a fragile individuality. It provides a location for political righteousness. It prevents the formation of the solidarities opposition to capitalism requires.

In the weeks and months to come, we can expect that liberals will continue to amplify identity, consolidating into the single figure of Trump the histories and structures of racism, sexism, and homophobia. This Trump-washing will make regular Republicans look reasonable and Democrats look like champions of equality and diversity. The hatred the Trump candidacy legitimized will take on a liberal form of hatred for working class white people, in the name of a multiculturalism that erases the fact of a multiracial working class. Communicative capitalism will provide the field of response — the circulation of outrage and righteousness, individualized statements of fear and alliance.

The left must respond by building solidarity. Taking the side of the oppressed means that we have to make sure the struggles of the oppressed appear as a side, a side in the class war that cuts through them all. We do this by pushing forward the communist actuality of Bernie Sander’s slogan, “Not me, us.” Or as Jed Brandt said in the election’s immediate aftermath, it’s time to be not allies, but comrades.

Jodi Dean teaches political and media theory in Geneva, New York. She has written or edited eleven books, including Crowds and Party, The Communist Horizon and Democracy and Other Neoliberal Fantasies.