Japanese Internment and the Media

Last week, the Los Angeles Times published two letters defending the US government's internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. The Times has since issued an apology.

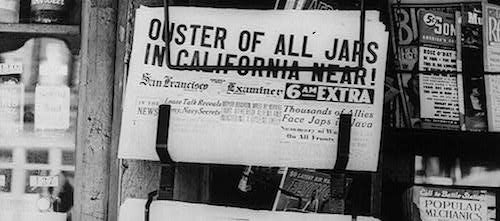

The apology does not mention the active part that the Times and many other metropolitan dailies took in fomenting vicious anti-Japanese sentiment and defending the forced removal of Japanese Americans. Below we present a brief survey of the role the American newsmedia played in Japanese internment, excerpted from Juan González and Joseph Torres' News for All the People: the Epic Story of Race and the American Media.

On February 19th, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the US military to exclude any resident of the country from certain designated military zones for national security purposes. Government officials proceeded to round up some 120,000 Japanese nationals, more than two-thirds of them US citizens, and forcibly relocate them to military camps for the duration of the war. Japanese internment was to become one of the most shameful government actions in the nation’s history. Critics saw it as a gross violation of democratic principles and due process rights, especially since US participation in the war was aimed at defeating Axis aggression and the Nazi ideology of racial supremacy. More than forty years later, Congress finally apologized for the internment policy and awarded $20,000 in compensation to each surviving victim.

Press historians, however, have paid scant attention to how biased press coverage fueled public hysteria against the Japanese. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, many of the country’s most influential newspapers backed the internment of first-generation Japanese immigrants (Issei), as well as second- and third-generation Japanese who were already US citizens. The Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, and New York Times were among the many papers that published stories questioning the loyalty of ethnic Japanese. Some stories even claimed local Japanese were helping their homeland government prepare an attack on the west coast.

Several California papers launched a crusade in support of Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, the Western Defense commander who claimed that a Japanese fifth column existed on the west coast. DeWitt openly framed his allegations in racial terms, stating:

A Jap’s a Jap, and that’s all there is to it. I am speaking now of the native-born Japanese ... In the war in which we are now engaged racial affinities are not severed by migration ... The Japanese race is the enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on the United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become “Americanized,” the racial strains are undiluted.

The day after Pearl Harbor, the Los Angeles Times reported that some Japanese could very well be upstanding good citizens, but “what the rest may be we do not know, nor can we take a chance in the light of yesterday’s demonstration that treachery and double-dealing are major Japanese weapons.” Later, the Times called for the removal of the Japanese, declaring, “A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched — so a Japanese American, born of Japanese parents, grows up to be a Japanese, not an American.”

Scripps-Howard columnist Westbrook Peglar advocated executing a hundred detained Japanese for every American killed in the war, suspending habeas corpus for all Japanese, and placing them under government surveillance. While a few papers initially defended the Japanese minority, even those papers changed their tone after government officials warned of possible spies among the immigrants. California Attorney General Earl Warren, for example, testified to Congress that the nation was being “lulled into a false sense of security” when it came to Japanese at home. “Our day of reckoning is bound to come,” warned Warren, who would later become chief justice of the Supreme Court. On December 13th, the New York Times reported that US and Mexican government sources were concerned about unidentified aircraft flying near a secret airbase in the Southern California desert, where a large population of Japanese was “rumoured” to reside.

At the same time the federal government began subsidizing radio portrayals of the Japanese as subhuman. In the Treasury Star Parade, a federally sponsored series aimed at promoting the sale of war bonds, one episode, titled “A Lesson in Japanese,” described the Japanese as monkeys and reptiles and still “savage beast[s].” Another depicted a scene of an American soldier dismembering the genitals of a Japanese soldier.

Little wonder that public feeling against the Japanese was far greater than against German nationals. A survey by the US Office of Facts and Figures in April 1942, for example, found three times as many Americans backed war with Japan as with Germany. In a separate survey by the Office of War Information, respondents commonly described Japanese as “sly,” “cruel” and “treacherous,” while they described Germans as “warlike,” “cruel” and “hardworking.” Admittedly, some of this was due to the simple fact that Japan, not Germany, had launched a direct surprise attack on US territory; still, the ferocious cruelty Americans countenanced toward the Japanese during the war was bewildering. In a Pulitzer Prize–winning study of the Pacific conflict, historian John Dower called it a “bloody racist war.” It was “virtually inconceivable,” Dower noted, “that teeth, ears, and skulls could have been collected from German or Italian war dead and publicized in Anglo-American countries without provoking an uproar, and in this we have yet another inkling of the racial dimensions of the war.”