Eulogy

Kate Millett remembers her mother.

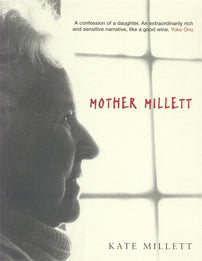

Kate Millett, the writer, artist, and activist whose Sexual Politics (1970) was an early intellectual touchstone of feminism's second wave, died last week at the age of 82. Over the course of her life, Millett remained an active participant in movements around gender, sexuality, mental health, prisons, and human rights; she made art in multiple media; and wrote books on a variety of political, literary, and autobiographical subjects.

Mother Millett, published by Verso in 2001, is a memoir of the final years of her mother's life and a reflection on daughterhood. "I began writing about my mother, little sketches for myself, and largely about myself, in 1985," Millett writes,

when my elder sister, Sally — a lifetime sibling rival and always a critic of considerable acumen, older and wiser and more practical in so many departments of life through her training in political history, diplomacy and international relations, her practice in law and banking — forced me to pay attention and understand that our mother Helen Millett could actually die and indeed was old and recently ill enough to do so certainly, and perhaps soon.

The first three sections of the book are as much about myself as about my mother: indeed as Sally has often observed, I rarely write about any subject except myself, so that there is a good deal of the egocentricity and ambition of the artist come home to confront her past in her parent and her town. Mother Millett was of course the catalyst but not the main player yet — not until reality takes over in Part Four, halfway through the book.

The eulogy below forms a coda to the book.

Crossing the ocean, coming home to her funeral, I realize her suddenly. Mother, childhood, tomato soup and the kitchen chairs with round backs we called “peanut butter” chairs. Every inch of the house on Selby Avenue clear and felt. Riding to America on Aer Lingus only hours away from the phone call in the middle of the night. Surrounded by this catastrophe; so long awaited, so unprepared for. Seven hours with nothing to read, no escape valve, no distraction. Only this bewilderment in a crowded cabin over water, the sound of the engine, the pain a constant and obdurate force around this chair suspended in nothingness. Relentless and pushing to a crescendo. Words come and with them tears. Words themselves, she gave me language. How much she taught me of literature, Shakespeare and Synge and Shaw, of the role of speech, the ring of a line, how a word could hit the mark, the success of it.

And people and judgment. And kindness, the tact that averts a quarrel, gentleness, the habit of peace. And determination when propitiation wouldn’t do finally and you had to go back to principle and speak up. Courage and toleration and fairness. The fact that she once expelled a wedding guest from her house in the midst of his own festivities for a joke she regarded as anti-Semitic. I know Martin Luther King and Gandhi through her. And Richard Wright and the Death of a Salesman. And Riders to the Sea. Also her deliberate and lady-like honesty over money or the truth, the limits of a white lie or courtesy or charity. Suddenly I remember every callow remark and superior opinion of my own, how I carped and contradicted.

It is a long time since Helen Feely Millett has been as we once knew her. But then we knew her real self far longer, only in the last years have we had to watch the inches and inches giving way to death, to infirmity, our enemy the tumor paralyzing her. Our enemy age and frailty. Her strength, then surrender. In a sense we lost her even before we lose her now, the going from us gradual, as if we were being seasoned to bear it finally. Only by degrees having to take on that dreadful singular state in the world — motherlessness.

As I copy out these words Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony is playing, one of her favorite pieces of music. She was our America, the daughter of immigrant farmers, Minnesota pioneers in Farmington. She was also our Ireland, its virtues and memories and landscape. She was, finally transcending the limitations and particulars of her early years, a wise internationalist with a vital and unfailing concern not only for business but politics and peace and justice. I explored the meaning of the 500th anniversary of Columbus and the European devastation of the Americas with her in the months following her surgery when I was able to care for her and teach her to walk again, safely restored to her beloved Wellington where she spent the last two years of her life. I was also able then to read her the first two chapters of The Politics of Cruelty, a book she encouraged and urged forward during the seven years of its composition, the wisdom of her world view being my reference point and beacon the long while I worked on this book. Hearing the sad news of how the gulag and the death camps had restored the practice of torture to the modern world, she sighed, “I’m not sure I wanted to know this much before I died . . . but then, imagine what they knew.”

I see her now as a pioneer, a brave and lonely groundbreaker in her time and place; troubled, afraid but having to be brave and finally triumphant in her integrity. It stands before us now as a challenge, daunting in its example, radiant and complete now entirely visible.

I want to say that we do not lose the ones we love in death, we incorporate them. If we have imagination we absorb the dead rather than relinquish them. One need hardly assume the leap of faith into a hereafter. Here and now as long as I live I will bear her with me, not a voice from outside my mind but from within it. Helen Millett — that soul, its fallibility as well as its grandeur — surer now, less timid and uncertain than in life, less harried, even braver than her familiar courage and certainty — quicker on the draw — surer now for being an extract, a concentrate, that essence, that bullion cube of rectitude and common sense.

A small woman in a little woman’s body, that frail and vulnerable being. That figure habitually ignored or derided and passed over, incarnate in human flesh — it is this I celebrate as a tower of integrity, a conscience and a will. Imperishable bone — flesh of her blood in all I do hereafter, remembering her, becoming her.

My sisters too and all their progeny — all who through kinship or contact — she made us. Carefully and deliberately, no maker of souls worked more consciously in her creation. And we must cleave together agreeing and disagreeing, even agreeing to disagree, separate but individual — this above all was her wish. That we remain in love in fellowship, in harmony and continuation. That what she held together never be sundered by her transformation into spirit.

Ashes to ashes — we are all on our way to death — we are all going there . . . and know better now that it is what we bring with us, what knowledge we acquire along the way, that matters. A terrible solitude is still before me and will last all the days of my life. But having assumed her one can endure for she is not departed but present. She enters and dwells within, as time passes more and more comfortably, transformed and transforming energy and spirit. So that we need not say hail and farewell . . . but welcome.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]