Against the criminalisation of street harassment in France

An open letter by French feminists and researchers into gender violence in opposition to a proposed law to make street harassment an infraction.

First published in Libération.

In late September the question of street harassment again came onto centre-stage in France. The Secretary of State for Equality between Women and Men, Marlène Schiappa, announced that she together with the Interior Minister was preparing measures to police street harassment. A few days later, a few lines appearing in Libération explained that a working group was going to be tasked with putting forward a law to make street harassment an infraction, and thus criminalise it.

This question is nothing new. It expresses the transformation of feminist mobilisations that have taken place since the 1970s, denouncing the control that men exercise over women’s bodies in public space. That control is exercised in the street, but also in other spaces open to the public, from hospitals to universities, leisure spaces or workplaces.

More recently, complaints against "street harassment" have spread on social media. These reports have offered us an insight into the banality of acts, remarks, and even insults and attacks assaulting women in the street. Insofar as one of the two parties explicitly refuses or shows no interest, such acts are not the same as simply "hitting on" someone. These situations are so many ways of limiting women’s ability to make use of public spaces.

One might be pleased that women’s right to the city is the object of public attention. Nonetheless, this criminalisation bill poses problems. And the difficulties that Belgium faced when it implemented an arsenal of such measures show as much. In 2012 Brussels introduced administrative sanctions against street harassment and sexist insults. Two years later, a law against sexism in the public space was adopted and applied nationwide. Yet very few cases were reported. After all, as in the case of other attacks on women’s bodies, the burden of proof continued to weigh down on the women concerned. What is more, these fresh infractions overlapped with an already-existing legislative arsenal.

Similarly, in France, insults, harassment and physical and sexual assaults are already considered infractions. So why create a specific infraction, when it would suffice to train actors on the ground in order to drive them to change their practices? The penal system already struggles to get a grip on the crimes of rape and sexual assault. So it would be better to develop the training of police, judicial, and legal personnel. Such training should explain the workings of sexual violence and the continuum that exists between all these forms of violence, in all public spaces.

We might legitimately ask why there is this desire to criminalise. Particularly at a time when this government is mounting drastic budget cuts hitting the feminist associations that promote women’s rights, and notably those at the heart of the struggle against gender violence.

When the category "street harassment" is inserted into the penal domain, the street again becomes the target of public policy. At the same time, this also means targeting the populations who occupy this space, who often belong to impoverished and racialised layers. Other terminologies could be used instead, in order to emphasise that the control over women’s bodies is not only exercised in the street, but also in the workplace, in universities, in leisure spaces, and even in women’s homes.

So the problem of this category, and even more so the plans to police and criminalise it, is that it circumscribes a specific category of acts judged unacceptable — street harassment — and a category of people — men from the poor and racialised classes — that will be judged particularly problematic. Yet we know that young men from the poor and racialised classes are already more than anyone subject to police control and violence by the forces of order. So we might legitimately fear that this new infraction will strengthen this state of affairs.

To police or criminalise street harassment offers no answer to the various different forms of constraint on women’s bodies and women’s mobility, in the street as elsewhere. To create a new infraction will but reinforce the repression and control over men from disadvantaged categories. We are feminists and researchers into gender violence, and this is indeed a question linked to women’s rights. We oppose a criminalisation that will serve to designate what forms of sexism are legitimate and illegitimate. For it will serve to keep in the shadows other forms of sexism, committed in well-to-do neighbourhoods and big companies, which will remain legitimate and above reproach.

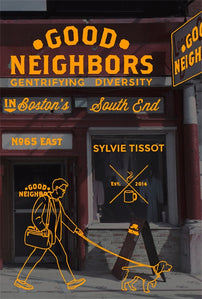

Elizabeth Brown (Université Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris-I Natacha Chetcuti-Osorovitz Centrale Supélec and Idhes-ENS), Alice Debauche (Université de Strasbourg), Pauline Delage (Université Lumière, Lyon-II), Eric Fassin (Université de Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Paris-VIII), Claire Hancock (Université Paris-Est Créteil), Maryse Jaspard (Université Paris-I Panthéon-Sorbonne), Solenne Jouanneau (Université de Strasbourg), Hanane Karimi (Université de Strasbourg), Amandine Lebugle (Ined), Véronique Le Goaziou (Lames-CNRS), Marylène Lieber (Université de Genève), Marta Roca i Escoda (Université de Lausanne), Sylvie Tissot (Université de Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Paris-VIII), Mathieu Trachman (Ined).

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]