'There is always in history this possibility of the unexpected': Interview with Carlo Ginzburg

Carlo Ginzburg, author of The Cheese and the Worms, is one of Europe's most influential historians. In this interview with Claire Zalc, Ginzburg discusses the influence of his parents - the novelist Natalia Ginzburg and scholar of Russian literature Leone Ginzburg - his childhood in Fascist Italy, historical method, Aby Warburg, and the continuing importance of historical scholarship.

Carlo Ginzburg’s fine escapes by Guillaume Calafat and Claire Zalc

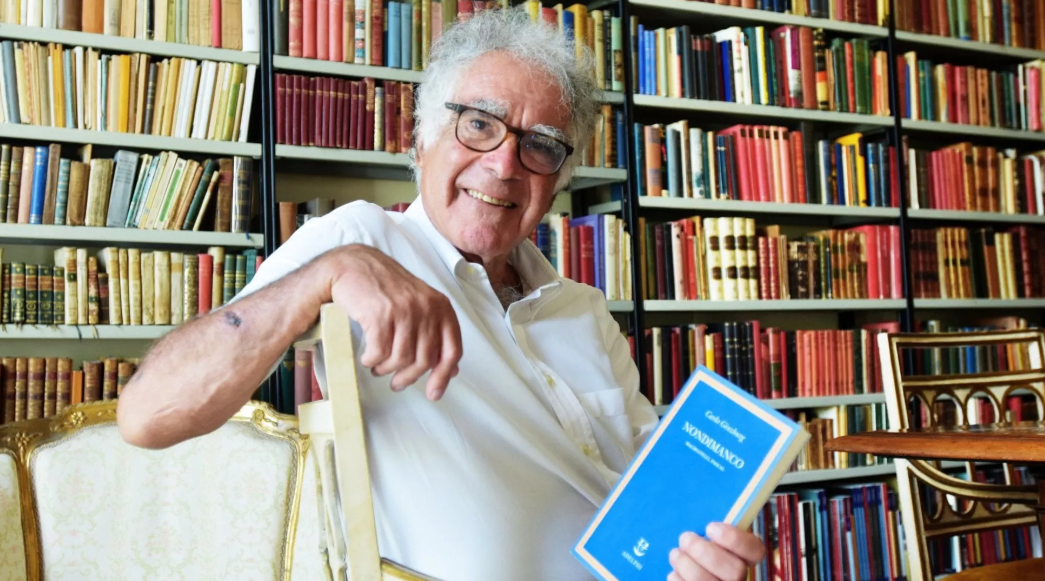

From the Inquisition to Machiavelli, from Dante to art history, this insatiable inquirer likes the stimulus of documents from the past, while always tracking details and anomalies in the archives. An encounter in Bologna, amid his extraordinary library.

Carlo Ginzburg suggested that the interview take place in Bologna, in the building where he lives. This is on a beautiful square in the city centre, a stone’s throw from the former Jewish ghetto. The city is bathed in sunshine. There is the murmur of a thousand tongues, tourists still numerous at the end of the summer. Ginzburg opens the door with a broad smile. We follow him through an astonishing maze of corridors, walls covered with shelves, a sequence of rooms in which tables and desks are weighed down by opened books and thick files of papers and documents. A library with a feel of Borges – though perhaps Ginzburg’s inspiration is the immense library of art historian Aby Warburg, who interested him so much. In a small office also full of books, the historian, born in 1939, answers our questions in a precise and careful French. The window is open, and behind the ochre roofs you can see the two medieval towers that dominate the city.

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]Exceptional curiosity

Carlo Ginzburg speaks as readily as he writes. You have to cast off and travel with him from island to island in the company of Aristotle and Benvenista, Stendhal and Dante, or Machiavelli and Pascal, the subjects of his latest book, Nondimanco (‘nevertheless’, not yet translated). He proceeds by associations of works and ideas, which he deploys with virtuosity and enjoyment. In his mouth, the adjective ‘magnificent’ recurs to describe in turn a book, a sentence, a notion, a comma. However, Ginzburg’s immense erudition, as one of the founders of ‘microhistory’ and probably its greatest representative, is not designed to intimidate. It is driven by an insatiable curiosity and a constant taste for discovery. He likes to tell how he randomly selected files from the Venice state archives – a procedure he calls ‘Venetian roulette’ – or let himself be guided by chance connections of titles in a computerized catalogue.

His most famous book, The Cheese and the Worms (1976), starts from the trial of a Friuli miller, Menocchio, who was brought before the Inquisition in 1583 for his idea that the universe was like a cheese in which angels (including God) appeared in the way that worms did. Ginzburg developed a number of hypotheses to understand this heretical cosmogony which led the miller to be condemned to death. When studied in depth, with a magnifying glass, his case facilitated an exhumation of peasant cultures in history. More broadly, it is from the particular case that Ginzburg develops his methodological thinking, rather than the other way around. The Cheese and the Worms was a huge publishing success, translated into more than twenty languages. It helped to spread, not without some misunderstandings, the approach of microstoria or ‘microhistory’, a veritable historiographical revolution of the late 1970s and early 1980s, which brought together a group of historians (Giovanni Levi, Edoardo Grendi and Carlo Poni among others) around the magazine Quaderni Storici. Despite their very different objectives, their works all promoted experimentation and the in-depth observation of ‘exceptional’ situations, with the aim of challenging the great simplifying narratives. Ginzburg opened the ‘Microstorie’ collection, published by the Turin firm Einaudi (co-founded by his father), with The Enigma of Piero in 1981. Here he proposed a radical reinterpretation of the work of Piero Della Francesca based on newly discovered documents about the painter.

Tracking down witches

Carlo Ginzburg grew up in the midst of books. His mother, Natalia, was one of the great novelists of the twentieth century; his father, Leone, a Jewish immigrant from Odessa, was a specialist in Russian literature. After house arrest as an antifascist, he was imprisoned for resistance activities, and died after torture in a Rome prison in 1944. Young Carlo was then just six years old. His family history gave Ginzburg the privilege of an early socialization to classical culture, and an intimate knowledge of the violence of persecution that permeates his work. He was initially attracted to literature. In the Turin circles of the prestigious publishing house Einaudi, he became friends with Italo Calvino and was deeply influenced by the work of critics such as Leo Spitzer and Erich Auerbach. He returns to this in his essays on Laurence Sterne, Primo Levi and Dante. Nevertheless, it was to history that he turned during his studies in Pisa, at the Scuola Normale Superiore, where his teachers introduced him to Marc Bloch’s The Royal Touch and the virtues of slow reading. As a young historian, he set out on the track of witches in the archives of the Inquisition; he then discovered the benandanti of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, ‘those who walk for good’ at night, spiritually fighting the forces of evil in order to ensure the fertility of the harvests. This research led to his first book, The Night Battles, published at the age of 27. The chance discovery in the Vatican Library of a werewolf from Livonia in the eastern Baltic, who also claimed to be combatting witches, had strange echoes of the benandanti. Ginzburg explored these remarkable similarities between Northern Italy and the Baltic in Ecstasies (1989), analysing different forms of repression of the marginalized – women, lepers, Jews, Muslims and Siberian shamans. In this wide-ranging book, Ginzburg championed the interest of a fruitful encounter between history and morphology. For him, the study of temporal changes (history), along with that of the similarities in form and type (morphology) that can be identified in different contexts, sometimes thousands of years apart, reveal chains of ancient transmissions and forgotten and buried borrowings.

Anomaly hunter

Carlo Ginzburg likes to be surprised and stirred by documents from the past. He happily identifies flaws, aberrations and anomalies, which he argues ‘are richer than norms, because they reflect deviations and transgressions from the norm’. He himself uses the metaphor of hunting in a famous article on method. ‘Morelli, Freud and Sherlock Holmes: Clues and Scientific Method’ compares the art connoisseur who identifies details (Giovanni Morelli), the detective looking for clues (Sherlock Holmes) and the psychoanalyst in search of symptoms (Sigmund Freud). ‘There is always something in a text, even the most controlled one, that escapes its producer – a blind spot,’ he explains (see the interview below). This is what the historian seeks to track down: ‘escapes’ that allow him to go against the obvious, even at the price of irritating specialists in fields where this permits impressive innovations, from art history to Machiavelli or religious anthropology.

Ginzburg invites us to free ourselves from specialisms and other reserved terrains. As he often repeats: to learn or discover something, we must fully recognize the stimulating role of ignorance. This is the principle he has conveyed in his teaching, at the University of Bologna, at the University of California at Los Angeles, then at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, where he has ended his academic career. Lucio Biasiori, one of his students, agrees: ‘Carlo Ginzburg sometimes says that he likes to teach, but prefers to learn. This is a provocation, because the two activities are intimately linked in his case. When he teaches, he transmits research being done, at the same time as always having an extraordinary availability to learn from everyone.’

The historian Simona Cerutti, with whom he co-edited the Microstorie collection, also underlines what she owes to Carlo Ginzburg’s ‘extraordinary intellectual generosity’: ‘During my doctorate, he did not hesitate to invite me each month to talk about my work for a whole day; he was incredibly available and we discussed hypotheses and possible connections. He fed me in every sense of the word, even offering me excellent meals and a huge sandwich for my return trip!’

[book-strip index="2" style="display"]The requirement of truth

With Ginzburg, intuitions and hypotheses are always accompanied by rigorous checking. ‘He recommends us to “flirt” with our research hypotheses,’ says Biasiori, ‘but then be absolutely inflexible when it comes to checking them. In his words, nothing is more instructive than a hypothesis that collapses. This demand on himself and others is a defining feature of his character.’ While he willingly emphasizes the share of contingency in his work, Ginzburg never deviates from a constant demand for truth. He forcefully denounces the dangers of the widespread relativism and scepticism that have spread to the California campuses where he taught between 1988 and 2006. Ginzburg also uses this demand in battle. He does not despise the ‘balance of power’ (Rapporti di forza is title of a volume of his collected essays). His tone can be controversial, even aggressive, as when he accused the French religious historian Georges Dumézil of Nazi sympathies, which caused him some tenacious enmities.

His battles also led him into the judicial arena to publicly defend his friend Adriano Sofri, a far left activist accused of having ordered the assassination of police commissioner Luigi Calabresi in 1972. As if he was dealing with a sixteenth-century Inquisition trial, Ginzburg began to examine 3,000 pages of documents and files.[1] His work gave rise to a book, The Judge and the Historian, which, if it failed to clear Sofri, met with a wide response, offering powerful reflections on the status of evidence and the value of clues. In 2007, Ginzburg signed a petition against a bill in Italy that aimed to criminalize denial of the Shoah, finding it an absurd idea to entrust judgement on historical truth to the courts. He certainly rejects the claims of those intellectuals who claim to speak with authority on every subject. But he is well aware that the age of Trump and Salvini requires new stances and new forms of engagement. He refused to go to the Turin book fair last May because of the presence of neo-fascist publishers. Today, he accepts requests to speak about migrants in Italy, or to speak in Russia at the invitation of the Memorial organization, on the memory of repression and the defence of human rights.

The devil’s mischief

Carlo Ginzburg is certainly a specific intellectual, as Michel Foucault defined this, but on a world scale, travelling from Chicago to Tokyo, Lima to Berlin, Moscow to Jerusalem. He was delighted to hear African students in London applaud a text in which he gave voice to the indigenous revolt in the Mariana Islands. History is not only an inexhaustible material for reflection, it is also a magnificent instrument for changing people’s minds.

Ginzburg says he is fascinated by what he does not control, the reappropriation of his texts and the blind spots in his own work. Faced with this, we quickly realize that we too, historians playing at journalists, are watching in vain for something that ‘escapes’ him. A certain mischievousness never leaves his gaze, the mischief of the heretic, the witch and the devil, as whose advocate he willingly serves. Isn’t it said that the devil (Warburg would say God) hides in the details, those details that interest Ginzburg so much? We end the interview though we’d happily continue for hours. But the bells of Bologna have struck noon. It is time to leave the books, the library, the references, history. To find ourselves under the sun of ‘Red Bologna’, to regret already that time has passed too quickly, to regret ‘the thickness of this moment’.

Carlo Ginzburg: ‘There is always in history this possibility of the unexpected’

Invited to the ‘Rendez-vous de l’histoire’ at Blois, this great Italian intellectual is one of the founders of ‘microhistory’. The man who has studied witches, werewolves and other victims of the Inquisition, continues to fight against neo-scepticism today.

Carlo Ginzburg, 80 years old, is one of the most outstanding historians of the last fifty years. His book The Cheese and the Worms (1976), translated into more than twenty languages, is considered a manifesto of Italian microhistory. By closely examining the story of a miller from Friuli sentenced to death by the Inquisition, he showed how an exceptional case can reveal something essential about the cultures and societies of the past. A prolific author who has tackled the history of persecutions, heresies, and the marginalized of modern times (The Night Battles, Ecstasies), art history (The Enigma of Piero), philosophy and literature (No Island is an Island), he is the guest of honour at the ‘Rendez-vous de l’histoire’, which runs until Sunday. An opportunity to look back together with him on his journey, his work and his commitments.

[book-strip index="3" style="display"]Interview with Claire Zalc

From Dante to Piero Della Francesca, Sherlock Holmes to the Inquisition trials, your work impresses by the erudition it deploys.

I think we have to accept ignorance. We have to start from there. If we accept ignorance as a starting point, we can learn something. Sometimes you initially feel you have found an answer; then you have to work to trace the question, or the questions. We start with a set of associations: possible connections, linked to specific contexts. But we can also turn to morphology: it is then a question of recognizing similar elements, asking ourselves at what level and in what sense. There is this wonderful phrase from art historian Aby Warburg: ‘The book you need is right next to the one you are looking for.’ It’s the law of the good neighbour. I am obsessed with this idea of chance and the possibility of producing it, for example by working on catalogues. Once, I decided to search all the words of Voltaire’s Treatise on Metaphysics, using the UCLA library’s computer catalogue. In doing so I stumbled on a work from 1718 by Jean-Pierre Purry, an author I absolutely did not know, a Calvinist born in Neuchâtel. I followed his traces in Neuchâtel, then in Purrysburg, a colony he founded in South Carolina, and I wrote an essay on him (Latitude, Slaves and the Bible), which I defined, in the subtitle, as ‘an experiment in microhistory’.

Is that what you like about being a historian?

I like everything. Leafing through a catalogue is exciting, checking dates... As my friend Paul Holdengräber puts it, ‘I prefer everything.’ There is always in history this possibility of the unexpected – which you have to tease out, of course. Microhistory, which involves the careful, complex and detailed study of a case, allows us to reflect on the relationship between norms and anomalies. The latter are more interesting, cognitively richer than norms. An exceptional case can function as a revealing one. But the question of truth, and of proof, is more important now than ever. We must not forget the example of Lorenzo Valla, when he demonstrated in the fifteenth century that the Donation of Constantine, an apocryphal document granting the Pope sovereignty over part of the West, was a forgery. I have spent decades fighting against neo-scepticism. I’m now working on ‘fake news’.

In 1989, you published Ecstasies, in which you analysed the persecution of the marginalized. You say you chose to study witches because it reminded you of the stories of your childhood...

Among the books I was reading at the time was a collection of tales by Luigi Capuana, a nineteenth-century Sicilian writer. In one of these, a young girl enters an empty palace and sees a tiny being, wearing a turban with a long feather, who says to her, ‘I am Gomitetto.’ I remember the illustration, beautiful. You could see the meeting with Gomitetto, then you turned the page, and Gomitetto had become a werewolf and attacked the girl. I remember how I kept turning the pages, Gomitetto, then the werewolf – and I found Gomitetto much scarier than the werewolf. Many years later, I started working on witch trials. From the beginning, I told myself that in these trials I wanted to capture the voices and attitudes of the persecuted. I did not immediately understand the almost paradoxical side of this gesture, this choice: to work on the persecuted on the basis of the archives of the Inquisition. Then, over the years, I rediscovered my childhood curiosities. I even stumbled by chance on the trial of a seventeenth-century werewolf! I have just spoken about the personal, almost intimate side of my research. And yet, it spoke to a lot of people. The success of my book The Cheese and the Worms was obviously unexpected. I believe it is due to the voice of the main character, the miller Menocchio; but also to the questions raised about the challenge to authority, the encounter between the printed book and oral culture.

What was your family background?

A family of intellectuals. My father, Leone Ginzburg, was born in Odessa in 1909. At a very early age he began writing essays on Russian literature, he translated Gogol, Tolstoy... He taught at the University of Turin for a year, then, having refused to take the oath to the fascist regime, his academic career came to an end.

Did he already have Italian nationality?

Yes, my father’s involvement in the antifascist movement dates precisely from the moment he obtained Italian nationality. He belonged to the group Giustizia e Libertà, led by Carlo Rosselli. My own name is Carlo Nello: the first names of Carlo Rosselli and his brother Nello, killed by fascists in France in June 1937. During my youth in Turin, I became friendly with Giovanni Levi, another of the founders of microhistory. We used to play football together. We both came from Jewish antifascist Turinese families with close ties. His name is also Giovanni Carlo Nello.

What about your mother?

My mother was the novelist Natalia Ginzburg. She wrote a book, Family Lexicon, in which she talks about her own family. I grew up in a family where there were books everywhere. I understood the social privilege I had enjoyed when I entered the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, where I met young people from quite different backgrounds than mine. However, growing up in a family of Jewish intellectuals is an ambiguous privilege. In 1938, my father was denaturalized. When Italy went to war alongside Nazi Germany in 1940, he was sent under house arrest to Pizzoli, a very isolated village at the time, not far from L’Aquila in the Abruzzo. My mother, with her two children, joined my father there; my sister was born in L’Aquila. When the fascist regime collapsed and Germany occupied Italy in 1943, my father went to Rome. He ran an underground antifascist newspaper, L’Italia libera. He was arrested, recognized and imprisoned by the Germans. He was tortured and died in prison in February 1944.

It was also during the war that your grandmother explained to you that you had to change your name and call yourself Carlo Tanzi. Would you say that’s the moment when you became a Jew?

There is one word I don’t like at all, and that’s the word ‘identity’. The word is a political instrument used to draw barriers, boundaries. In my case, ‘being Jewish’ meant ‘becoming Jewish’ because of persecution. I was 5 years old when my maternal grandmother, who was not Jewish, explained to me that when I was asked ‘what is your name?’ I had to answer ‘Carlo Tanzi’. That moment has remained unforgettable for me. Then, of course, things change. Being Jewish, in the American academic context, means something completely different. I remember one day, at the University of Los Angeles where I taught for a long time, I was talking to someone. A colleague came by and said with a smile, because I was making gestures: ‘Jew, Italian!’ It was around the same time that I asked myself another question: why was I ashamed of Berlusconi? It was not a feeling of guilt, but shame. I lived in the United States, I taught there, but I was not ashamed about Guantánamo. I was certainly horrified, but it was not shame. I then realized that it is our own country that we can be ashamed of.

What is ‘your’ Italy exactly?

I was born in Turin, but I don’t feel like I’m from Turin. I have lived most of my life in Bologna, but I don’t feel like I’m from Bologna. On the other hand, when I arrive in Pisa, I get off the train and have the feeling that everything is familiar. Italy has this polycentric side, very different from France, which makes it a continual surprise, an inexhaustible reality.

How do you define the boundaries of your commitments?

I must say that I don’t like sermons. If there is anything I can do, as a historian, from an analytical point of view, it is very good. It’s part of my job. But the situation is evolving in a way that I may have to get a little more involved. Yesterday, I was asked to comment on the screening of a film on immigration and I accepted. Would I have said yes five or ten years ago? The context is changing... Even if the idea of the committed intellectual is not something I particularly like.

Do you think that doing history helps us understand our present? I have in mind the frequent analogy made between the current situation and the 1930s.

I had never used the word ‘fascist’ outside its historical context. Then I watched Trump’s election campaign on TV. I was in Chicago, and I thought, ‘This guy’s a fascist.’ Then I thought about a conversation I had with Italo Calvino, around 1968. He knew Argentina well, and said to me: ‘You see, in the light of the Perón experience, the definition of fascism has to change.’ This struck me. Certainly, there is historical fascism, but can we broaden this definition? Racism or anti-Semitism are not, in my opinion, necessary elements. But we should think about this.

Why do history today? Do you think it still makes sense?

Yes, completely. But we must avoid confusion or identification between history and memory. Even if history is nourished by memory, and memory is also nourished by history, it is necessary to keep this distinction: Maurice Halbwachs demonstrated this very well. It reminds me of the Internet. There are, with the Internet, gains and losses. We gain a potential for opening up, for ‘de-provincialization’, which is magnificent. But there is also a risk of losing the slowness of reading, the slowness of reflection. You have to play between the two, speed and slowness, to regain the thickness of the present.

[book-strip index="4" style="display"][1] See the documentary film by Jean-Louis Comolli, L’Affaire Sofri, 13 Productions, 2001.