In Tribute to Meredith Tax

Verso editor Jessie Kindig remembers socialist feminist activist and author Meredith Tax, and we reprint the 2021 introduction to Tax's classic of socialist feminist labor history, The Rising of the Women.

Meredith Tax, dynamic voice of socialist feminism for over fifty years, passed away recently at the age of 80. Meredith was one of a generation of women I have learned from and looked up to all my life.

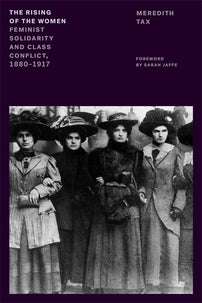

I'm happy to say that we can count Meredith among Verso's authors, for we just last year released Meredith's important work of American socialist feminist labor history, The Rising of the Women, in our Feminist Classics series. Rising is a classic that examined the fraught alliances between working-class women and middle-class women, and the possibility for what Meredith called "a united front of women." I remember reading an old secondhand edition raptly in my dorm room as a college student: I had read socialist labor history, but I hadn't ever read socialist feminist labor history -- but here it was, bringing together what often felt like unreconcilable parts of my political world!

I never met Meredith in person -- she was already ill when we signed her book -- but even over the phone you could tell that she was dynamic, restless, driven, and had a wry sense of humor. Just a few moments from her life: as a young activist, she was kicked out of the Leninist October League for criticizing their treatment of women, and rankled Planned Parenthood by pointing out their sterilization abuse of poor women and women of color. A part of the socialist feminist New York left in the 1970s and 80s, she never stopped working; most recently, documenting the struggle of Kurdish women fighters in Rojava and the new forms of demcoratic feminism they were building in the midst of war.

Meredith helped to found CARASA, the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse, one of the foundational reproductive justice organizations in the Americas, as well as the PEN America Center Women's Committee -- and I'm sure, a host of other things. A true heir of the "bread and roses too" tradition, she even wrote novels about bohemian life in Greenwich Village!

Below is her 2021 introduction to The Rising of the Women -- a fitting tribute to the work she's left us with, which will guide us in all the work we have yet to do.

– Jessie Kindig,

Brooklyn, NY, 2022

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]Forty Years Later

In the late seventies, when I wrote The Rising of the Women, most of the US left thought revolution would come via the classical Marxist strategy of building the labor movement until it was strong enough to form its own political party and, through elections, command the heights of government. The anarchist version of this strategy was that the labor movement would gain power through a general strike, not the vote. In both cases, women were but an adjunct to the main protagonist: the (white) male worker whose courage and collective strength would transform society and free us all.

Almost 175 years after the publication of The Communist Manifesto, nothing remotely resembling either scenario has yet taken place in the United States. There have been many attempts to explain why the Marxist model couldn’t be implemented, from the continual availability of new farmland as the frontier extended and indigenous peoples were killed off and expropriated, to the constant flood of new immigrants who could be used to break strikes and the divisive effects of racism in a system founded on slavery. All of these factors distinguished the US economic system from the nineteenth-century English capitalism on which Marx based his paradigm—though, as Cedric Robinson points out, the economies of England and the rest of Europe incorporated slavery from the time of ancient Athens. Robinson believes Marx’s desire to produce elegant theory led to serious oversimplifications. “Fully aware of the constant place women and children held in the workforce,” he writes, “Marx still deemed them so unimportant as a proportion of wage labor that he tossed them, with slave labor and peasants, into the imagined abyss signified by precapitalist, noncapitalist, and primitive accumulation.”

As I worked on The Rising of the Women, I too had doubts about the reliability of Marxist revolutionary predictions—partly because the US labor movement had only a fraction of the strength of its UK counterpart, but principally because the theory excluded women and community organizing. By 1984, I had lost so much faith in the paradigm that, when I made a speech for Monthly Review, which had published The Rising of the Women, I focused on the socialist tradition’s neglect of women’s organizing:

A pattern of male repression, exclusion, devaluation and just not getting the point runs like a thread through the history of the left. With few important exceptions, left-wing movements have been overwhelmingly led and controlled by men and serviced by women: men making speeches, women making coffee. As a result, our hundred-odd years of socialist history is lopsided, reflecting the ideas, history, and experience of only half the species. Within left-wing organizations, the “woman question,” as Leninists quaintly call it, is commonly treated as a petty-bourgeois diversion from the class struggle, its concerns trivial items to be placed on the bottom of an agenda and skipped for lack of time. Women who try to stimulate discussion of it are normally encouraged to tum their attention to more important matters… The socialist movement has paid the price for such stupidity. Its theory does not accurately describe the world and its practice does not prefigure any future society most of us would want to belong to. No wonder it has reached an impasse. How could a theory and practice based—at best—on the experience of only half the human race possibly be adequate?

Today I would go farther, possibly even as far as Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned former Marxist guerilla and ideological leader of the Kurdish freedom movement, who said, “The role the working class have once played, must now be taken over by the sisterhood of women.”

Theories about the failure of Marxism in the United States also overlook a crucial aspect of US history: every time a progres- sive movement became strong enough to cause concern, the state came down on it with a heavy hand, murdering, jailing, blacklist- ing, and deporting as many leftists as it could find. This happened in the Red Scare following World War I, the McCarthy period, and the attacks during the sixties on the civil rights and antiwar movements, particularly the Black Panthers.

With this history in mind, and in light of the current danger from the extreme right, I believe our strategy for profound social change in the United States must be based not only on the labor movement, but on two other nineteenth-century movements, those of Black people and of feminists, both born in the struggle to abolish slavery. Against a state as powerful as this one, only a united front that bring these movements and labor together will have enough muscle for serious transformation. And time is running out.

The Current Crisis

We are at a turning point in human history. The climate emergency demands that we immediately move from a fossil fuel–based economy to one that is environmentally sustainable. This will require drastic political and economic changes. Nor is the climate crisis the only one we face: by October 2021 the COVID-19 epidemic had already produced over 242 million cases, according to the World Health Organization, and it has not yet run its course. The economic depression resulting from the epidemic is likely to doom millions more to homelessness, hunger, and unemployment.

Climate change, COVID, and the economic slide have put overwhelming stress on a system that had already reached its breaking point. In the last thirty years, global economic integration based on free market ideology has led to obscene wealth for a very few and desperate poverty and uncertainty for most. The decisions that shape today’s world are more often made by trans- national corporations than by governments or national elites. Unwilling to relinquish the power they once had, some members of these elites support right-wing politicians whose appeal is based on a toxic brew of racism, fundamentalism, hatred of women and LBGTQ+ people, and paranoia about cultural dilution by migrants. With help from the religious right, a new axis of fascist politicians has come to power, including Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey, Boris Johnson in the United Kingdom, Narendra Modi in India, Benjamin Netanyahu in Israel, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and Donald Trump here in the United States.

These politicians, and the right-wing movements behind them, are a danger not only to democracy but to life on earth itself, for their disregard for climate change will make it even more difficult to deal with global warming. Lacking the legitimacy that comes from solving real social problems, they rule by force, fear, and deception, relying on the military, police, and support from fundamentalists and a captive media to contain popular dissent. In order to build their base, they target minorities, migrants, women, and LGBTQ+ people; undermine basic democratic rights like voting, assembly, and freedom of speech; and invoke religion to attack the very idea of universal human rights. Some are open fascists; others are willing to accommodate fascism.

Politicians of the center, who spent the last thirty years cheering market solutions and unrestrained economic growth, were unprepared for the cascade of crises we now face. Their main fix for the problems of late capitalism has been austerity and further shredding of the social safety net; their response to climate change has been slow and inadequate; and too few have fiercely opposed the rise of right-wing movements. They are not strong enough by themselves to turn back the extreme right.

The rise of this new global axis demands a united front against fascism comparable to that of World War II and late-twentieth-century movements in China and Vietnam. These were all led from the left. But the reborn US left is young, and, like a toddler, is still learning to walk.

Its rebirth began with Occupy Wall Street in 2011. That led to the Bernie Sanders campaigns of 2015 and 2019, which in turn led to the resurrection of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) as a mass organization, and the election of new progressive politicians to a host of offices. Black Lives Matter (BLM), a movement against police brutality and a racialized justice system, began in 2013 with mass protests against the acquittal of the man who killed seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin. This led to the formation of the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), a coalition of over a hundred abolitionist, anti-capitalist groups, while BLM itself went on to build a national network that protested the murders by police of Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and many others, culminating in the vast mobilization after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. But where is the comparable progressive organization or network focused on women’s issues? It doesn’t exist. This is a problem not just for feminists but for all of us, because the organized strength of women is needed to fight fascism.

Suffrage and the United Front of Women

In The Rising of the Women, I use the term “united front of women” to mean a broad women’s movement of different classes in which socialists must fight for their own political goals without destroying the unity needed to move forward. The suffrage movement in the early part of the twentieth century drew in everyone from millionaire J. P. Morgan’s daughter Anne to socialist union organizer Clara Lemlich. Each faction fought for leadership, but while the Anne Morgans had money and social status on their side, socialist feminists did not even have the full support of the left for women’s suffrage. Anarchists and syndicalists thought the vote was a bourgeois distraction, while some socialist politicians feared that women were so backward they might all vote for capitalist parties.

Still, most progressives saw the vote as a basic democratic right that should be extended to women as well as men. In this period the Socialist Party was large and mass-based and elected many local and state officials; socialist Eugene V. Debs won more than 900,000 votes in the 1912 and 1920 presidential elections. The party’s founding program in 1901 included equal rights for men and women. When it did nothing to put this position into practice, socialist feminists around the country organized local women’s groups. These women were not separatists by choice; they wanted access to the party’s national reach. So, in 1908, they submitted two resolutions to the party convention: one to set up a Women’s National Committee, the other for a women’s suffrage campaign. When both resolutions passed, they set to work. A year later, the party had ten times more female members.

But how were they going to approach the suffrage movement, most of which was anti-labor, anti-immigrant, and racist towards Black women? They had three options: work within existing suffrage organizations as individuals; build socialist suffrage organizations that could participate in the movement alongside mainstream organizations; or form socialist suffrage organizations that would criticize the movement from the sidelines rather than collaborate with the bourgeoisie.

To find out what they did, you will have to read Chapter 7. But these strategic questions confront the left in any united front situation: do you give up your independence to be part of the action, build your own organization and fight for leadership in the broad movement, or stay pure on the sidelines? A mature left is capable of working with liberals without forgetting its objectives or losing its soul. An infantile left is not. But without their own autonomous women’s organizations, left-wing feminists cannot fight for leadership within the united front.

Feminism and the Left

In my preface to the second edition, I painted a picture of the feminist movement in 2001: many sectors, each with its own objectives and style, but still demonstrably part of one movement. Look for feminist organizations today and what do you see?

There’s #MeToo, an unquestionably powerful movement against job-related sexual harassment and assault, with a huge impact. But because it is a campaign, not a membership organization, there is no way for people who support this movement to ensure either consistency or accountability. Then there’s the Women’s March, which started out strong after Donald Trump’s inauguration in 2016, staging the largest protest in US history: up to a million people in Washington, DC, and between 3 and 5 million people in the United States as a whole. But because it was a campaign originated on Facebook, its governance was up for grabs, and it has had many ups and downs since 2016. Reproductive rights organizations, notably Planned Parenthood, and the reproductive justice movement have been on the front lines against the right-wing religious assault on women since the late seventies. Now, as many states pass laws cutting off access to abortion, spontaneous groups funding women’s travel to abortion clinics have sprung up. All this is well and good. But multi-issue left-feminist organizations are also needed if we are to defeat the right.

The history in this book shows what happens when women rely on progressive groups led by men to do feminist organizing, and the US left today is a long way from grasping feminism, let alone integrating it into a general political program. In 2008, Linda Burnham, an experienced Black left-wing feminist, did an in-depth study of US grassroots organizations’ approach to racism and sexism, interviewing leaders of eleven community organizing groups, mostly people of color. She found that while all of them had a structured program to deal with racism, not a single one had anything comparable on sexism.

Our generation learned about sexism the hard way. One of the igniting events of women’s liberation was the 1969 counter-inaugural rally in Washington, DC, which made the limitations of the antiwar movement extremely clear. When Marilyn Webb and Shulamith Firestone came onstage to read a women’s statement, the predominantly male audience shouted them down, yelling, “Take them off the stage and fuck them!” Dave Dellinger, who was chairing the rally, responded by telling the women to leave the stage. Furious, they went home and started women’s groups.

Women in the Black movement faced similar hostility. Their voices were deliberately excluded from the 1963 March on Washington, and Fran Beal, who fought the sexism she found in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), remembers the pushback she encountered when discussing abortion rights for Black women: “We were called lesbians and dykes. They accused us—this was from the SNCC people—they accused us of dividing the movement. They said, That’s not as important as race.”

Today, many feminists work inside and often lead unions and left-wing organizations. But their personal feminism cannot trans- form the overall consciousness of these groups, much less the progressive movement as a whole. Such large-scale transformations in consciousness do not come about merely by women winning over their male colleagues. Autonomous feminist groups are needed to push from the outside at the same time.

The work of the Illinois Women’s Alliance discussed in Chapter 4 and the history of the shirtwaist strike in Chapter 8 show how much can be accomplished by a united front of women with progressive leadership. The story of the Lawrence strike in Chapter 9 shows what more can be done when a strike unites the entire working class at both the union and the community level. And the struggles over socialist suffrage work in Chapter 7 shows what happens to women’s work when the left disregards it, or when its male leaders feel threatened by feminist activism, and the women involved have no independent organization that can keep their issues alive.

Today a large and aggressive right-wing movement is on the attack against feminists, queers, and especially transgender people. At a time when the right is led by angry white men and religious fundamentalists, it is critical for progressives to fight attacks on trans people while strengthening the fight against patriarchy in general. Only by doing both can we build a progressive movement that will fight for all of our rights, not play one group off against another. Everyone in this movement needs to understand gender, patriarchy, racism, and class, and the specific ways they intersect and overlap. In addition, progressive feminists have to build both our own independent organizations and a broad united front of women, and work with and within the left to achieve our common social justice objectives. Unless we can do all these things, and fight climate change at the same time, we will fall short. And failure could mean the end of human life on earth.

Notes

“Fully aware of the constant place...” Cedric Robinson, “Preface to the 2000 edition,” Black Marxism, London: Penguin, 2000, xlix.

“The US labor movement had only a fraction of the strength of its UK counterpart...” In 2020, only 10.8 percent of the US workforce were unionized; most of these union members were government workers. “News Release,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 22, 2021, BLS.gov. In the same year, 23.7 percent of workers in the United Kingdom were union members. D. Clark, “Percentage of Employees That Are Members of a Trade Union in the United Kingdom from 1995 to 2020,” June 7, 2021, Statista.com.

“I made a speech for Monthly Review...” In the end, my speech proved too heterodox to be published in Monthly Review and ended up in Dissent: “The Sound of One Hand Clapping: Women’s Liberation and the Left,” Dissent, Fall 1988, available at MeredithTax.org.

“The role the working class have once played, must now be taken over by the sisterhood of women...” Abdullah Öcalan, Liberating Life: Women’s Revolution, Cologne, Germany: International Initiative and Mesopotamian Publishers, 2013, 52, Freeocalan.org.

“In 2008, Linda Burnham, an experienced Black left-wing feminist, did an in-depth study...” Linda Burnham is an American journalist and organizer in women’s rights movements, particularly those serving women of color. She was a co-founder of the Third World Women’s Alliance and founder of the Women of Color Research Center in Oakland, and is now research director for the National Domestic Workers Alliance. The study is here: Linda Burnham, “The Absence of a Gender Justice Framework in Social Justice Organizing,” Center for the Education of Women, University of Michigan, July 2008, CEW.UMich.edu.

“We were called lesbians and dykes....” Fran Beal, interview by Loretta Ross, March 18, 2005, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, p. 40, cited in Burnham, “The Absence of a Gender Justice Framework.”