Bernstein at the Waldorf

Bradley Cooper’s Maestro reveals a reflexive effort to defang the radicalism of the first great American conductor while covering the tracks of an oppressive regime.

It’s a dreary day in Manhattan in March of 1949. In mere months the United States will lose its global monopoly on nuclear arms to the Soviet Union, which will just as soon find itself accompanied by Mao Zedong’s united China. Oblivious to the enormity of the conflict ahead, an envoy of Soviets trudges through dirt blackened snow, past thousands of nuns and American Legion picketers into the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in midtown. Among them apparatchiks of the Soviet state, KGB stiffs, and a delegation of intellectuals headed by the writer Alexander Fedeyev and composer Dmitri Shostakovich. Though the obsession with the thought of Soviet aggression has not yet gripped the public, twenty would-be artist-ambassadors are already absent, their visas having never cleared the U.S. State Department.

High above them in room 1042, America’s counter to the Soviet delegation is hard at work finalizing months of careful preparation. Here, idealogues work to establish a sort of think-tank whose goal to convert the momentum of this global peace summit into an intellectual spearhead rightward involves breaking from the union-friendly communism of the 1930s toward the interventionist liberalism which came to define cold war partisanship. These are erstwhile Marxists and bourgeois anti-communists like the writers Mary MacCarthy, Robert Lowell, Nicola Chiaromonte, eventual New York Review of Books founder Elizabeth Hardwick, labor reporter Arnold Beichmann, and Sidney Hook—the philosopher to whom room 1042 is booked.[1]

In the ball rooms below, black tie anti-communists feign greetings and dialogue before reporting back to the nerve center in room 1042. They are the public arm of the intellectual insurgents; artists first, but true-believers nonetheless: Igor Stravinsky, Benedetto Croce, T.S. Eliot, Karl Jaspers, and Bertrand Russell, to name a few. Some successfully plant in the hotel’s mail room, manipulating press communiques and outbound letters from Soviet and American communist party organizers to those eagerly waiting outside. Each group flocks to the highly anticipated event for a chance to further their own ideological agenda on the global stage, eager to emerge the champions of American anti-communism. The ideological project was so clandestine that protest drills like mass umbrella stamping and lock-ons were planned should the bad-faith cabal be exposed by those who naively lent their energy to the project of American-Soviet peace.

Despite it all they too shuffled in, past Catholic picketers and tabloid photographers, into little black books carried by freshly hired waitstaff. In their company is the American maverick, composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein.

‘The age of anxiety’

Bernstein's attendance at the Peace Conference at the Waldorf would give Hoover’s FBI sufficient cause to nationalize an operation to surveil the conductor, but it was far from the beginning of the agency’s surveillance campaign against him. The collection of incidental information on the musician had been ongoing since the mid 40s—his participation in at least a dozen activist organizations such as the Civil Rights Congress and Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee had been on then Attorney General Thomas Clark’s radar for some time, as had his affiliation with known communist composers Marc Blitzstein, Earl Robinson, and his mentor Aaron Copland. Those disparate investigations by confidential informants and FBI boogeymen were now organized into one centralized dossier, to be coordinated as an ongoing surveillance campaign. The short term rationale for running Bernstein up the chain was to establish whether to authorize him to conduct a concert for Harry Truman and Israel’s president, Chaim Weizmann.[2] But long term, the dossier would become a massive surveillance enterprise which haunted the musician for much of his life.[3]

Bernstein’s appearance at something as anti-American as a peace conference was no small issue to the State Department. As the dust settled over Europe, federal operatives grew increasingly concerned at the idea that the U.S. was just one slice of a geopolitical pie. This was the time to consider which artists and intellectuals should be allowed to champion the capitalist regime. Bernstein’s extensive dossier—spanning four volumes at over 800 pages deep—follows him anywhere he lectured, conducted, performed, and traveled for leisure. Great efforts were taken by the American state to tap phones, intercept mail, interrogate friends, attend concerts, record lectures, snoop through luggage, infiltrate meetings, and collect garbage. The FBI would use every crumb to accuse Bernstein of secretly holding a communist-party membership in a series of accusatory episodes which grew ever more desperate.

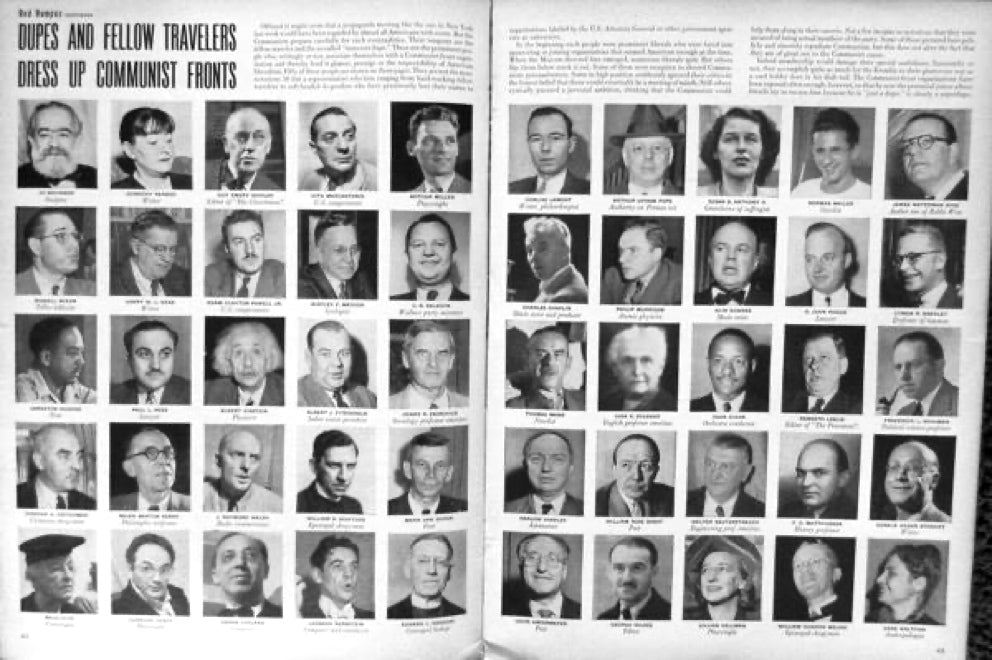

Shortly after the Astoria-Waldorf conference, LIFE ran a spread which named 50 suspected communist intellectuals who had made an appearance at the event.[4] Among them were Dorothy Parker, Albert Einstein, Corliss Lamont, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein. In the midst of the ensuing media frenzy, the American conductor’s name appeared alongside Copland’s in the FBI Security Index, an extra layer of repression that exposed both musicians to internment in a concentration camp in the event of a national emergency. This was the same act which required members of communist organizations to register with the attorney general, and which authorized significant anti-communist surveillance efforts within the various branches of the U.S. government and armed forces. Ideology, alone, had become both a crippling fear and a potentially devastating weapon for the capitalist regime.

Even Bernstein’s parents found themselves stalked, their lives documented by the state. This not only for their relation to him, but for their Ukrainian-jewish origin. From 1951 to 1956 Bernstein was blacklisted from appearing on CBS, a measure which precipitated a long disengagement from serious conducting. His passport was revoked in 1953, only to be reinstated after submitting an 11-page testimony denouncing the Soviet Union and declaring unequivocally that he was not a member of the communist party. It was this testimony which would form the basis of an investigation which intended to simultaneously prove Bernstein’s party membership and punish him for it, through a felony fraud case. Despite mountains of documentation on Bernstein’s activist activity, actual proof of communist party membership was never obtained, and the case would dissolve.

[book-strip index="1"]

Even still, the FBI continued what amounted to an open-book investigative policy deep into the 50s and beyond, collecting affidavits and testimony from confidential informants as to Bernstien’s true communist nature. Soon after the above-board fraud investigation tanked, the FBI began leaking evidence it had gathered on Bernstein’s homosexuality to the press. Luckily for the Maestro, his reputation had eclipsed whatever scandal his handlers hoped to raise, but it didn't end there. His compositions were clandestinely copied and analyzed, leading to the FBI blacklist of Mass—a piece commissioned by Jacqueline Kennedy—suspicious of anti-war themes embedded within its Latin text. Rumors of the conductor’s communist and activist affiliations were then leaked to the press in another defamation effort. The surveillance would carry on until the dossier's last entry on November 18, 1974, a file request on the conductor made by Gerald Ford's White House.

This was Bernstein’s punishment not for bombing party offices, but for standing with African American civil rights activists on the public stage; not for colluding with ex-nazi politicans in South America but for joining with Soviet leaders in the cry to denazify western Europe; not for lynching African American men but for supporting Henry Wallace’s desegregationist bid for president; not for supporting fascist guerillas in the Third World but for signing a petition against Zionist occupation of the West Bank; not for betraying secrets to a foreign country but for attending a conference advocating for global peace, even as agents of the capitalist world order swarmed around him.[5] By all metrics this was an artist tortured and antagonized by a bloodthirsty, expansionist regime.

Best of all possible worlds

As Bradley Cooper’s Maestro makes clear, our culture industry is in no hurry to explore the untidy accounts of America’s left-wing icons. Their treatment in the era of McCarthy, Wood-Rankin, and COINTELPRO should hardly be a surprise in our time of labor awakenings and reeducation. What stands out now more than anything is the continued work by a broader cultural force to downplay the severity of American despotism. In effect the cultural cold war rages on—at least for the victors—propelled by the animus of its own propaganda. Maestro is its latest work, a biopic on a lifelong activist which depicts no activism.

Some mention of these issues would be low hanging fruit for a 2023 biopic, if only to throw some mindless intrigue into an otherwise tedious script. Even Oppenheimer had some words on red baiting, fixing its narrative around the ongoing consequences of McCarthy era policy. Yet, the reflexive effort to mitigate Bernstein’s activism persists.

In 2018, Jewish-American Civilization Professor Stephen Whitfield wrote a blurb on Bernstein’s brief tenure with Brandeis University. Although unintentional, he sums up Maestro’s reduction well: “International fame had long eclipsed whatever threat Bernstein faced in the years of his close association with Brandeis, and his liberalism rather faithfully mirrored the values of postwar American Jewry.”[6]

Whitfield’s treatment of Bernstein comes from the same act of self aggrandizement as Bradley Cooper’s. Both distill the bravery of postwar communist activism into the impotent liberalism of the 21st century. To place Bernstein in league with his liberals inevitably draws comparison to the liberals of our time—to suggest that blue wave democrats are fighting the same fight. The figure Whitfield and Cooper are searching for really isn’t Leonard Bernstein, it’s Sidney Hook—the true postwar liberal who betrayed the cause of civil and human rights with his red bashing, colluded with state department ghouls to punish American activists, and ultimately laid the groundwork for a mass anti-communism which blindly embraced decades of domestic repression, violent expansionism, and corporate extraction. This is to say nothing of the way both auteurs diminish decades of surveillance, ostracization and manipulation at the hands of a paranoid regime to “whatever” personal problems troubled the otherwise above-it-all Bernstein, conveniently bracing against residual red baiting in the process.

While Bernstein embodies the plight of the American left-wing throughout the cold war, his treatment as a cultural icon now speaks to a phenomenon that goes much deeper than one man. The continued depoliticization of recent history embodied by cultural products like Maestro is an act of capitalist revisionism which can’t help but profit on the subject of its reduction. Yet as an entertainment product for the cosmopolitan stratum, Maestro must proffer itself as brain food. It presents an ahistorical reading of an era defining relationship—the sexually deviant Bernstein and the domesticated Felicia Montealegre—skipping all the bits that still sit heavy with us in the process, faithfully traveling alongside the narrative which began with Sidney Hook in the Waldorf-Astoria. Not even the FBI smear-job over his sexuality merits more than a passing reference to “people talking”. Bernstein’s homosexuality has since been accepted, intellectualized, commercialized, but his communism has not.

The resulting product is marketed to the type of consumer who knows enough to care who Bernstein was, but not enough to regard his life any differently than they would the Hunter Biden sideshow. This is nutrient slurry trussed up as brain food for an incurious strata of media consumers—but this anticommunist defanging did not start with Cooper.

Librium

The aforementioned Soviet envoy Dmitri Shostakovich continues to suffer the indignity of Maestro, starting with the dubious 1979 book Testimony. Here, Solomon Volkov—a Soviet defector—took it upon himself to faithfully retell the story of a tortured genius trapped in the barbaric USSR. American Musicologist and Shostakovich scholar Laurel Fay was the first to uncover rampant plagiarism of earlier writing by the composer in Testimony, carefully placed alongside falsified passages by Volkov. Unfounded reports surround first hand biography, such as one story which tells of Shostakovich and his fellow musicians eating maggots to stave off hunger on the last train out of besieged Leningrad. The book continues to be a source of apparently unsolvable controversy, conveniently published four years after the composer’s death.

Volkov’s account rapidly changed the narrative surrounding Shostakovich in the west—decades of state honors, lavish conditions, popular support, and artistic conviction had all been a communist ruse. Just like everyone else in the Soviet Union, everything we knew about Shostakovich was a lie. A lifetime spent shackled in the dungeon forced to write hundreds of hours of socialist music. Pieces like his Symphony No. 7, which satirized the nazi goose step and valorized Leningrad’s defenders, quickly took on fuzzy new meanings as unspoken protests against Stalin and Khrushchev. Disrepute notwithstanding, the book was irresistible to a western musical audience obsessed with stories of Soviet brutality. It now has a life of its own as the mainstream framework from which we view the composer.

If Maestro is soylent then Testimony is one possible factory of origin—an important piece of reductio ad Stalinum which continues to fuel ever-embattled cold warriors in their search for a tragic 20th century artist. Graphic artists sell prints of Shostakovich bravely defeating Stalin with rainbows and music and love while conductors quote Volkov’s yellow press anti-communism before the anti-fascist Symphony No. 7, fueled by bourgeois music historians who inculcate their students about the hidden message behind every note. To them the composer provides a neat cover for the trauma of western life, the vaguely defined hero far removed from their own time and place.

[book-strip index="2"]

Bernstein saw a different reason to embrace Shostakoivch—he upheld his Symphony No. 5 and the proletariat aesthetic values it embraced as a model for our own young and impressionable nation.[7] Little did he know, Shostakovich would become a receptacle for the angst liberals feel when they step over the homeless on their way to the Met. Oblivious to their own ignorance, it never dawns on them that the romantic suffering they nervously fetishize happened on our side of the iron curtain; a suffering they perpetuate. Where are the prints of Aaron Copland killing Hoover with rainbows?

This is the fundamental question which Maestro accidentally asks; not why the state had a vested interest in distorting the truth of their day, but why the spirit of that effort presses on after the FBI vans have left. The answer is bound up in the dialectic of American culture: on one hand, these products are necessary to the exceptionalist narrative which paints American cold warriors as the architects of our now safe and dominant West. On the other, they are products of that West, and are necessarily formed by its ethos.

That Maestro upholds the liberal idea that the world is as it will ever be is not accidental, nor is it inconsequential. To take Cooper’s telling, only a few small adjustments are necessary—policy tweaks like diversity and equity—which we can confront by simply watching his film. In the same vein, products formed by the market regime necessarily uphold our image of it, and will only ever become more important to it. As the media apparatus of the old world gives way to the decentralization of Twitter and TikTok, more and more Americans are becoming aware of how their world—not just the United States—came to be shaped by projects like COINTELPRO, Paperclip, Mockingbird, Condor, Jakarta, and the Reagan Doctrine. These tellings might complicate our hard won hegemony, threatening to disrupt our stasis and drag us back to the dark days when Americans questioned not only the actions of their state, but the structures which hold it up. Just as capital needs us to believe CIA black sites are tools of democracy, so too does it need to turn the radical Leonard Bernstein into an ineffectual Pete Buttigieg.

To tell any other history would expose our freedom as only the freedom to buy; our romantic heroes as radicals who stood firm against the regime and lost. Their figures are now subsumed into the totality of the beast, the bravest faces among them printed onto popcorn tubs in a final act of humiliation. This is capital’s propaganda ministry, so sophisticated in its operation that we pay for our own indoctrination and thank God for the freedom to do so. This is the condition of industrial culture in the 21st century.

The true contribution of these media products isn’t their smarmy dramatization of cultural icons, but their documentation of our nation’s refusal to reconcile with the repression inherent to the market system, even as the danger of Cold War dissent fades in the rear view mirror. That was simply the ignition of a now passive yet dominant cultural apparatus whose inertia propels it further from its own origin, ever farther from the possibility of identifying the pad from which we launched.

[1] Frances Stonor Saunders. Who Paid the Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War (London, UK: Grant Books, 1999), 45-56.

[2] Federal Bureau of Investigations. “Subject: Leonard Bernstein.” 100-360261. Unsealed under the Freedom of Information Act. October 18, 1994.

[3] Ralph Blumenthal. “Bernstein Was Monitored as Late as 70’s.” The New York Times, May 17, 1995.

[4] Editorial Board. “Dupes and Fellow Travelers Dress up in Communist Fronts.” LIFE Magazine, vol. 26, April 4, 1949, 14. (See below)

[5] Eric A. Gordon. “Today in History: Musician/Activist Leonard Bernstein is Born.” People’s World. August 25, 2015.

[6] Stephen Whitfield. “Leonard Bernstein and the FBI.” BrandeisNow. October 22, 2018.

[7] Philip Gentry. “Leonard Bernstein’s The Age of Anxiety: A Great American Symphony during McCarthyism.” American Music, vol. 29, no. 3 (Fall 2011).

Below: LIFE Magazine spread: 50 suspected communists, vol. 26, No. 14, pp.39-43, April 4, 1949

[book-strip index="3"]