Sabri Hammoudeh: A life in exile

Testimonial 19 of our Palestine Uncensored series details the life of Sabri Hammoudeh, a Palestinian refugee who was displaced during the Nakba in 1948.

Sabri Hammoudeh passed away in the summer of 2023 at 83 years old.

I met Sabri for the first time at his flat in a duplo-block high-rise, a stone’s throw away from Notaufnahmelager Marienfelde, a transit camp through which 1.3 million East German refugees passed before they could start a new life in the West. Born in a village in Palestine that today houses the Ben Gurion airport, Sabri, together with 700,000 other Palestinians, was expelled in 1948. After living as a stateless refugee in Jordan, he arrived in Berlin in 1961 – the same year as construction started on the Berlin wall.

Sabri met me in the antique-filled hall. He still seemed young, even as someone who was prescribed medical podiatry and whose friends were appearing in death notices. His remaining grey hair lay flimsy around the back of his head, his green-brown eyes warm and body slender. He showed me into the flat, tastefully furnished with Persian carpets and French furniture.

“In 1961 I got a visa to come and work for Drexler, which manufactured subway trains in Munich. I was in no way desperate for Europe. After all the years in the refugee camp, I’d established myself and was working for an American pharmaceutical company. My job was to make contracts all over the Middle East and I was regularly in both Damascus and Tel Aviv. It was a good life, but rumours said that things could be even better in Germany. That you could earn enough to help your family.”

This dream turned out to be difficult to realize initially.

“It was one of Germany’s coldest-ever winters. I came straight from desert climate, it was minus twenty-two and my job was to clean rusty pipes. Outdoors. Even the boss was giving pity looks.”

With America’s investments through the Marshall Plan after World War II, the battered German post-war economy began to flourish and people spoke of a Wirtschaftswunder. The country was desperate for labor and busloads of Gastarbeiter – ’guest workers’ – arrived from countries like Italy, Turkey and Tunisia to work in the factories. Over fourteen million migrant workers came between 1955 and 1973. Working visas were issued for several years but the idea was that the migrants would then return. Little effort was put into integration, an oversight for which the second- and third-generation family members of the three million migrant workers who stayed are still paying the price.

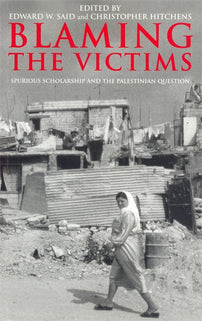

[book-strip index="1"]

“Us Palestinians weren’t particularly welcome, only fifteen years after WWII. We weren’t supposed to concentrate in one place. It was a sensitive issue for Germany. After the first month here I was ready to give up. There was an Iraqi car dealer living at the dormitory who’d just bought a new car. Join me - I’ll drop you off in Damascus before I continue on to Baghdad. I’d already said ‘yes’ and then the day before we were supposed to leave I got a job offer in Frankfurt.”

Then there was Elvira.

The unconventional Elvira had grown up in an intellectual home. Her mother had studied theater, her stepfather was a doctor and half the GDR’s intelligentsia came and went in their home in East Berlin. At sixteen, she left the GDR to marry her boyfriend in Ireland, only to return to West Berlin when the marriage fell apart. Elvira soon caught the Stasi’s attention and her Stasi-file is full of reports. Her flat is referred to as an “A foreigners’ meeting point” and “she spends a lot of time with Arabs.” Newspaper clips from 1967 reported that she was charged with supplying passports to the Soviet Union and was convicted to thirteen-months in prison.

“One day before she was due to be released I moved to Frankfurt. I didn’t want to have anything to do with this mess.”

By this time, Elvira’s father had also ended up in prison for illegal abortions.

Sabri had just settled when Elvira’s mother sent a telegram.

“Sabri, you’ve got to come back to Berlin and help us! A week later we were a couple.”

Sabri often visited the family on the other side of the Berlin-wall. After Elvira’s father lost his medical license the family had been in financial trouble.

“He had to haul coal. They wanted to humiliate him. I worked at a textile factory that made luxury ladies’ stockings. Every time we visited I put on three-four pairs under my trousers that they could then sell. One time we got caught and Elvira got a travel ban and couldn’t visit her parents for two years.”

Meanwhile they were supporting Sabri’s family in Jordan.

“My sister was living in a refugee camp with ten children in one room. We need to get you out of here” I said, but my dad didn’t want to. Where shall I go? I’ve got my friends, we can drink coffee and play cards. I’ve already lost everything once. We collected money and my sister laid the foundation of a house in Amman. Nowadays there are twenty-six people living there.”

Al Manarah, Jordan

Outside the muezzins buzzed like metallic insects bouncing between the buildings, spinning a melancholy thread of prayers and dreams. In the agora of the living room there was constant, low-level activity of tea, chatter and nieces in braided hair and in new dresses, with Palestinian embroidery, romping between the armchairs. It was like a week-long family celebration, most often with Sabri as the guest of honor. Constantly at his side was his wise and chatty nephew, Mohamad. While the rest of the Hammoudeh family were in holiday-mode with pistachio ice-cream and knafeh, Mohamad, Sabri, and I set off on a trip down memory lane through several places from Sabri’s childhood.

Mohamad drove past Amman’s Roman amphitheater and commercial shopping streets full of blinking signs and cafes. For tourists the country seemed like the oriental pearl in the holiday catalog. For others, it offered a low-intensity viewing point for a number of the complicated tragedies of the Middle East. Many, if not most with their roots in centuries of European colonialism and politics. Today it’s one of the countries with the greatest refugee population in the world in relation to its population. Not only hosting around 1.3 million Syrians, but also 2.3 million Palestinians.

“All of this is still a refugee camp” Mohamad said, as we swished past dilapidated flats.

“From the outside it might look like any other residential area, but the difference is in how densely populated and poor it is. The situation in Jordan is still far better than in many other countries in the region. We aren’t considered stateless here – ninety-seven percent have citizenship and we have far more opportunities. In Lebanon, Palestinians are banned from more than twenty professions and can barely own a home.”

We stopped at an association for descendants of the village where Sabri was born in 1939.

On the walls and in corners hung framed pictures of village-specific folk costumes.

“Our goal is to keep the memory of Kafr ‘Anar alive and make sure people don’t forget that we have a legal right to return according to UN Declaration 194” said the board member Abu Firas leading us to the holy crib of the venue. A detailed architect’s model of Kafr ‘Anar with houses, cornfields, bushes and water sources marked onto the paper landscape. Within a frame, a meter-long list with hundreds of names that had lived in the village before expulsion. As if in a trance, Sabri looked at the model.

“Good God. My childhood home was here! This was my route to school!”

Abu Firas pulled out his mobile and searched Google Maps for Kafr ‘Anar. The first attempt was fruitless, until it finally landed on a spot at the Ben-Gurion Airport. He zoomed in and out. An airport. The Israeli town of Or Yehuda with 37,000 inhabitants.

[book-strip index="2"]

“Last time we were there, we talked to some of the new residents, most of them Iraqi Jews. I met a farmer. He’d come in 1984 amidst the Iran-Iraq war. He said that deep down he knew it wasn’t his land. Like us, Arab Jews, lost everything and landed at the bottom of the social ladder.”

Back at Mohamad’s family house, he presented a laptop bag and started flipping through documents from 1930-1940s. Some were yellowed by the sun, others were slightly frayed at the edges. Temporary refugee passports, tax declarations and legal correspondence, all with a seal and signature in English, Arabic and Hebrew. So many cornfields, so many apple harvests shipped from Jaffa to Europe.

“And some claim that Palestine never existed.” said Sabri who kept flicking and found a document from 1947.

“I’ve always thought our land was seven thousand square meters, but this says ten thousand!? For a long time the Jews tried to get us to sell the land by legal means, but my father refused. It was how we earned our living.”

I asked him about the Nakba.

“The villages around Kafr ‘Anar were burning. At first people refused to leave and were ready to fight, but then the men realized their women and children were in danger. Many brutal massacres had already taken place, which had bred fear and rumours. It took two or three days to escape. Foxes and animals were screaming around the villages at night. As if they understood that something awful was going on. We were hungry and had no food.”

“Our parents all knew that their generation was lost.” Mohamad said. “Their only goal was that things would be better for their children. That we would have an education and be able to go to university. I was only six when I started working to help support my family.”

The Dead Sea

After a few days and eighteen thousand cups of coffee, cigarettes and makloubeh, Sabri had booked an all-inclusive for the entire family at the Dead Sea. The coach departed at five in the morning and for the first few hours most of the twenty Hammoudeh family members sat dozing in their seats. Behind me sat a wide-awake Sabri, mobile phone at the ready to capture the sunrise of the holy landscape of pre-Biblical caves and Mount Nebo. After breakfast the tour guide switched on loud music. Mohammed Assal’s Dammi Falstini boomed out of the loudspeakers. Three female cousins began clapping, at which point two aunts in sunglasses over their hijabs joined in singing. Fellow travelers began dancing as the first shoreline of the Dead Sea appeared as a blurry salt mist in the distance.

“On the other side our heart’s homeland!” shouted the guide at which half the bus burst out in a collective roar.

“Yalla Falestine” they clapped, exuberant, before the music was turned up again and the joyous dance now spread like a wave through the bus.

[book-strip index="3"]

Once we arrived, we took the beach bags to a water park where we spread out over sundecks. Palms, cement and cheery souvenir shops were framed by the reddish mountain landscape in the background. The entire Hammoudeh family’s worry lines seemed to fade under a joyous wave of snacking and paddling of feet in the pool. People bobbed up and down in the salty sea and rubbed black mud on each other’s backs. As the afternoon sun was setting, I found a diaspora uncle alone on a plastic chair looking out on the horizon. On the other side of the narrow lake you could see the silhouettes of Israeli hotels.

“I can’t cope with all the talk about Palestine. You can drown alive in it. I've suffered from depression for big parts of my life. Having to explain and discuss everywhere. It wears you out.“

He told me a story about going to a pharmacy for painkillers.

“I said a different brand please, this is Israeli. Such a shame that people need to fight over religion, said the cashier. We’re not fighting over religion! It’s about land. That a group of people can come and say hey, this land is ours now! But I guess the West just accepts this colonial logic – that’s how they’ve always lived. No, I don’t want to talk about this any more” he said, placing his hand on his heart.

“Where’s Uncle Sabri? He looked worried and headed down the steps to the private strip of beach belonging to the hotel.

A couple of meters out, Sabri lay paddling about in his sunglasses. In the lowest point of the world and the saltiest water on earth. Floating with his arms outstretched, he looked free.

If you have a story to share, please send it to pdiaries@verso.co.uk. We are publishing testimonies from all over the world. To see the full collection of testimonials, check out the Palestine Uncensored series' main page.