On Pasolini’s death

Il Manifesto, 4 November 1975

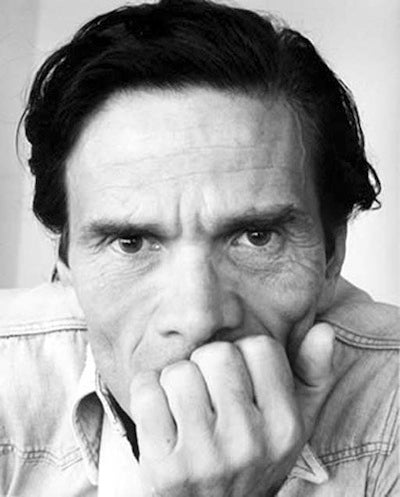

Translated by David Broder.The whole Italian press of both left and right speaks in pained tones as it weeps for Pier Paolo Pasolini, the most troublesome Italian intellectual of the last few years. Or rather, one who became too troublesome.

What he had been writing recently did not much please anyone. Not us on the left: after all, he railed against 1968, feminists, abortion and disobedience. Nor the right: for these forays of his were accompanied by a disconcerting reasoning, which the right found suspect, unusable.

Above all, his recent writing did not suit the intellectuals: for here they did the opposite of what they generally do, cautiously distilling words and positions as serene beneficiaries of the separation between ‘life’ and ‘literature’ – even those whom 1968 had given a bad conscience. Only one among them, Sanguinetti, in his piece yesterday, had the courage to say ‘finally we’ve shaken him off, this confusionist remnant of the 1950s’. That is, the apocalyptic, tragic years of division – which, for the leftist intellectual, were ultimately left behind. This near total unanimity is, of course, a second vehicle riding roughshod over Pasolini’s body. As with the first one, whoever has a clear conscience about it can say ‘he was asking for it’. For anyone who is not so sure, it is, instead, the last sign of this contradictory creature’s contradictory nature: and it is a real contradiction, not one that can be put back together again through some artificial dialectic. For if one thing is certain, it is that everyone suddenly recognising themselves in Pasolini’s thinking now that he has died – and died in this way – is truly our unloved world’s last piece of mockery against him. Because it is not the traditional homage to a deceased great man, nor the habitual absolution of a dead man hated when he was alive.

Everyone is now writing on the same register (in a box written in pained tones, L’Unità even sketched out a self-critique, while the Partito Radicale signed him up post mortem…) because they all today think that they can draw some advantage for themselves from Pasolini’s thinking. Did he not say that young people today are like the foam of a wave that has swept away the old values? That any collectivity must assume some order, a system of coexistence, a model? Everyone is in agreement on this, except that everyone attributes this order and this critique the characteristics that best suit their own purposes. Pasolini, having been the most outsiderish intellectual of Italian cultural life, through his indecorous death provided iron proof that this is no way of going about things. A proof so convenient that everything else can be pardoned.I think that Pasolini would have spat on this fervour and all that goes with it – if it is legitimate to imagine such a straightforwardly kind man doing such a thing. Who, if he had pulled through, would today be taking the side of the seventeen year old who beat him to death. He would be cursing his name – but taking his side. And so he would continue until his inevitable, perhaps foreseen and feared, death came the next time around. But he would be on his side, because it was in the world of youth, among these creatures with whom he was most truly alive (‘I really know these young people, they are part of me, of my direct, private life’) that he obstinately sought the light. In them; and not in the world of order – which does not only mean police stations.

He came back to this point time and again, because in his view of the world there was no other way. His attack on ‘development’, on the values of consumerism, of profit, and of the sameness that they induced in a preindustrial society in which personal, non-alienated, not passively accepted relations could still prevail was – as in general in this line of thinking, with its illustrious exponents both Catholic and secular – as one-dimensional as the society that he criticised. He lived this society as the end of history, as oncoming barbarism, faced with which you can only try to retreat. Retreat, in as much as a refusal of this kind of ‘development’ – and who could, except the periphery, or a Third World not yet at this level? – would not have offered any anchor of salvation. Elsewhere, he did not see salvation: and for this reason Pasolini stubbornly kept going back to the borgate [Rome’s slum areas], and the more they escaped from him the more agonised returns there he made. All the more so because in all senses they must have appeared to him as a frustration, a contradiction.

Is it that he sought an authentic relation but instead established a commercialised one? That he sought an open relation but instead himself repeated the relation between oppressor and oppressed – the rich intellectual arriving in his Alfa Romeo and paying the young guy who is so much more fragile than him, socially and personally? Neither could the humiliation that he must have received in exchange (how many trials, with less tragic ends than his death, he must have gone through: mockery by one-time comrades; rejection; the resistance of he who feels used and thus rebels…) absolve him from the fact that he himself was part of this alienating mechanism. In which his interlocutor ever more escaped him, becoming ever more his ‘object’. Different from how it once was, when the young guy went along with him but maintained his own character, an un-integrated dimension that could not be subdued, like Tommaso in Una vita violenta. Now that was true no longer: the guy who killed him had little in common with the borgata resident of once upon a time. He ought to be released tomorrow, in the sense of the values that rule this society (beyond an elementary humanity) because there is no doubt over his neighbours’ testimony, that is, that he had no great desire to work – who has? – but was ready and close to entering back into the family order, which he had violated only temporarily, if venally.

Nothing in this story is truly what it seems. Not the depraved rich man who sought hidden love among the marginalised – no one lived his homosexual inclinations more simply than Pasolini, and he could satisfy them without risks of this type in a now more permissive society. Nor the depraved youth, who is nothing of the kind: neither depravity nor delinquency, nor even voluntary deviancy, set him in rebellion against the norm.An accidental death in chasing a phantom, we might say. Satisfying for most, bitter for those who held Pasolini in esteem and respect. And the funeral now, with his glorious absolution by those who first built up and then exorcised this spectre. When Pasolini is today so praised, when – probably in good faith – so many people recognise themselves in his discourse, it is because for him ‘the other half’ that he saw as essential, and in which he placed his hopes, was baseless.

How many discussions we had, the few times I met him, and always the same: the ones he repeated just the same with Moravia. It is true that capital has dehumanised us. It is true. It is true that conformity to its model is monstrous. It is true that this is so powerful as a force that it is reflected even in those who reject it: in 1968, when he wrote his famous verses on the clashes at Valle Giulia, Pasolini saw in the student the product of a class who can ‘try their hand’ at revolution, while the policeman, the son of a southern farm labourer, is not at liberty to do so; and here he captured part of the truth. It is true that today, unlike yesterday, we can speak of abortion, not only because the feminist movement has ripened but also because male society is thinking about ‘economising’.

It is true that compulsory schooling and TV are organs of the prevalent consensus. It is true that the fascist is not so different from the democrat, in his cultural models, as in 1922. All true, and all partial: because each time Pasolini touched on these uncomfortable truths, he made a leap from the ambiguity of the present back to the unambiguous humanity of ‘before’, rather than identifying in the student, in feminism, in education, in conformity itself, the beginning of a way forward, though certainly only a hypothetical one. Pasolini grew ever further from the idea that we have to carry through this journey right to the end, and there to pick up again on the thread of a world given back to humanity. He could have been a sceptic, but became a ‘reactionary’ in the classic sense of the world.And this is today being exploited – and this is the second car running over his body. After all, nothing of the cutting, violent value of his ‘reaction’ remains in the first, second and third pages in the book of elegies dedicated to Pasolini. He will have a bourgeois funeral, and in time the Rome city council will name a street after him. They will kill him far better, his real enemies, than the boy the other night did. Before dying, Pasolini must have seen in this boy only the dead end into which he had been chased, only his error. And to think that he sought the angel of the passion according to St. Matthew.

See more from Rossana Rossanda here.

See more from Pier Paolo Pasolini here.