Joe Sacco's Introduction to Child in Palestine

As part of our graphic non-fiction week, we bring to you Joe Sacco’s Introduction to A Child in Palestine, a collection of cartoons by renowned Palestinian graphic artist Naji al-Ali, as well as some image excerpts from the book. Through his most celebrated creation, the witness-child Hanthala, al-Ali criticized the brutality of Israeli occupation, the venality and corruption of the regimes in the region, and the suffering of the Palestinian people, earning him many powerful enemies and the soubriquet “the Palestinian Malcolm X.” He was assassinated in London in 1987; the people and organization behind this attack remain unknown. But it is clear that there were many who wanted to stop his evocative political cartoons.

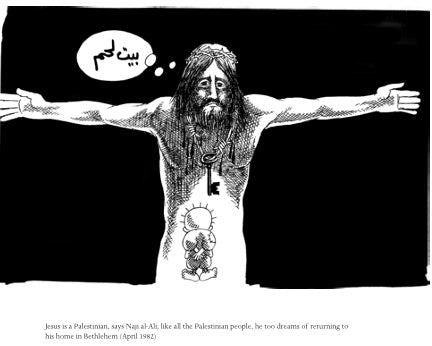

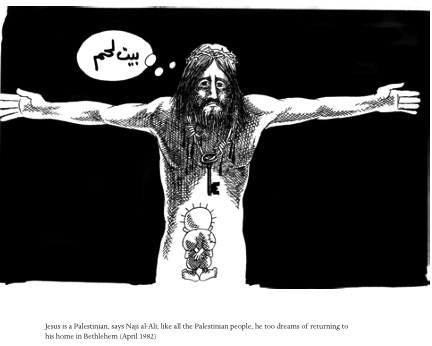

Jesus is a Palestinian, says Naji al-Ali; like all the Palestinian people, he too dreams of returning to his home in Bethlehem (April 1982)

I owe a debt to Naji al-Ali, that most renowned of Palestinian cartoonists, who was assassinated in London a few years before I first heard of him. When I made my initial trip to the Occupied Territories in the early 1990s to gather material for what would become the comic-book series Palestine, I was more than a little reluctant to tell my Palestinian hosts that I would be depicting their stories in drawings, as cartoons. Would they think I intended to trivialize their oppression?

I needn’t have worried. Upon blurting out my approach, a smile of understanding usually creased their faces. Of course! We had our own cartoonist! Naji al-Ali! And little by little, by such encounters, I began to recognize that my way had been well paved by this man, al-Ali. He was talked about with deep respect bordering on reverence. He criticized everyone, I was told, Israelis, the PLO, Arab regimes. No one knows who killed him. Everyone had reason. I was introduced to his iconic character Hanthala, the obviously destitute but upright Palestinian child, always with his back to the viewer, looking on at some scene of Israeli cruelty or Arab hypocrisy. Hanthala represents the Palestinian people. He is us. I began to notice images of Hanthala everywhere, tacked up on walls or worn as ladies’ jewelry. And on one occasion, in a cinderblock home of a refugee, someone pointed to a framed portrait on the wall. Hanthala’s father, the man himself, Naji al-Ali.

Films come to an end, but the reality of Palestinian suffering is ever present ( July 1980)

He was born in the Galilee in the village of al-Shajara in 1936 or 1937, and expelled, together with hundreds of thousands of other Palestinians, in the 1948 war that created Israel. His family settled in the Ain al-Helweh refugee camp in southern Lebanon. Dispossessed, growing up amidst the squalor and hard- ship that has been the lot of so many exiled Palestinians ever since, he quickly be- came politically conscious. He later said, ‘As soon as I was aware of what was going on, all the havoc in our region, I felt I had to do something to contribute somehow.’ He vented his frustration in marches and demonstrations that sometimes landed him in jail. It was in those periods behind bars, on the walls of his cells, that he ex- perimented with a means of self-expression more suited to his artistic sensibility: po- litical drawings. He started embellishing the walls of his refugee camp in the same way. Encouraged by others in these artistic endeavours, he spent a short time attend- ing the Lebanese Art Institute until he ran out of funds. Like many other talented Palestinians with few outlets in the early 1960s, he emigrated to newly independ- ent Kuwait, which was in the midst of an oil boom. He stayed there doing various magazine jobs until the early 1970s. It was in Kuwait, as he felt he was ‘slipping into the life of luxury’, that he first doodled Hanthala, who, in al-Ali’s own words, ‘represented the honest Palestinian who will always be on people’s minds.’ The very idea of creating a character that would epitomize the poorest, most powerless Palestinian, must have sobered al-Ali, who saw Hanthala as a separate moral entity ‘that stands to watch me from slipping.’

Back in Lebanon, drawing for the newspaper As-Safir, Naji al-Ali placed Hanthala in the foreground of his cartoons, gazing at not just scenes of Israeli oppression and violence but also of Arab corruption and inequality. Everyone who ran roughshod over the Middle East’s downtrodden was al-Ali’s target. As he saw it, ‘My job was to speak up for the people, my people who are in the camps, in Egypt, in Algeria, the simple Arabs all over the region who have very few outlets to express their points of view.’ His slashing attacks were always politically insightful, but it was Hanthala that made them personally meaningful for al-Ali’s many readers. ‘[Hanthala] is actually ugly,’ admitted al-Ali, ‘and no woman would wish to have a child like him.’ Perhaps it was for that reason that Hanthala was affectionately embraced as a symbol by the poorest Palestinians; he reminded them of themselves – impoverished, unwanted, the orphans of the Middle East. But Hanthala was something else, too – he was knowing.

It is the silent stance that must have delighted Hanthala’s admirers. His arms are not by his side as in surprise or shock. They are behind his back, hands together, as if inspecting. Hanthala’s stance says, Don’t mind me. I’m off to the side. Watching. Recording. And I know exactly what you are doing.

The united Arab ‘football team’, wearing the colours of the US flag and UN resolution 242, attempt to score in a bricked-up Israeli goal (September 1983)

In Lebanon in the ’70s, during the civil war and under Israeli attack, al-Ali felt he was at his zenith. ‘I stood facing it all with my pen every day. I never felt fear, failure or despair, I didn’t surrender . . . My work in Beirut made me once again closer to the refugees in the camps, the poor, and the harassed.’ But in 1982 Israel invaded Lebanon, seeking to crush the PLO once and for all. Hundreds of Palestinian refugees were massacred by Israel’s Lebanese Christian allies in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Beirut while the Israeli army sealed off the area. Al-Ali was devastated. He made his way back to Kuwait. In some of his cartoons, Hanthala lost his cool. He raised his hands in anger. He threw stones. Al-Ali’s work had ruffled the feathers of Arab elites for a long time. He was expelled from Kuwait and moved to London.

By now al-Ali was famous. His cartoons appeared throughout the Arab world, and in London. He continued battering at the oppressors and the privileged of the Middle East despite death threats. On July 22, 1987, he was shot in the head by a lone assailant as he was walking into the London offices of the Kuwaiti newspaper Al-Qabas. He lay in a coma for five weeks and then died. He was about fifty years old. The identity of the killer has never been determined.

Hanthala stands on the divide between seated veiled and unveiled Arab women as they eye each other suspiciously (undated)

Naji al-Ali remains a hero in the Arab world, in particular to the Palestinians, who say his name with the same tenderness with which they mention their great poets. His iconic figure, Hanthala, remains a potent Palestinian symbol and will for a long time to come. Unfortunately, with the Middle East’s twin taps of violence and despair still open, there is all too much for Hanthala to see.

Joe Sacco

January 2009

A Child in Palestine is on 50% off till the end of this week, alongside our other graphic non-fiction titles available here.