"I have no delusions. I am playing"—Leonora Carrington's Madness and Art

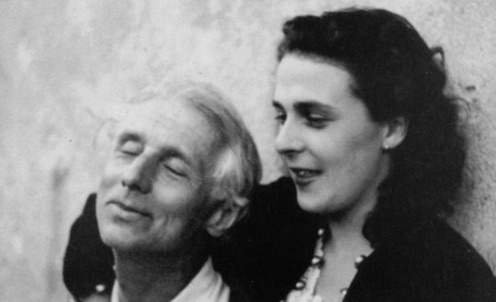

Leonora Carrington was a prolific artist and writer, and one of the few women in the surrealist movement. Until recently, she was perhaps more famous for her personal life than her work (besides the riotous novella The Hearing Trumpet): after running off with Max Ernst, she suffered a breakdown and ended up in a Spanish asylum, from which she was rescued by her nanny in a submarine.

Joanna Walsh examines the intertwining of madness and art in surrealism and how Carrington refused the surrealist romanticisation of female madness, describing her time in the Spanish asylum in terms of a forced incarceration. Through her life and work, Walsh traces Carrington's rejection of patriarchal authority through her political activism and through the creation of dreams, myths and symbols centred around the feminine in her art.

This article is part of a series for World Mental Health Day 2015.

“I begin, therefore with the moment when Max was taken away to a concentration camp for the second time…” This is how the author and artist Leonora Carrington opens her memoir of madness, Down Below.

Leonora Carrington, the daughter of a wealthy British industrialist, had come to France in 1937. An art student, she had met Max Ernst, the established Surrealist artist twenty-six years her senior, during the 1936 London Surrealist Exhibition. Ernst left his wife and set up home with Carrington, first in Paris, then in the South of France, where he encouraged her painting and writing.

In 1941 Ernst was interned in a French prison camp for the second time, leaving Carrington in Saint Martin d’Ardèche. After an unsuccessful attempt to plead for his freedom, she returned to their home where the locals looked on her suspiciously, “like some sort of performing animal, a bear with a ring in its nose.” She suppressed her despair and loneliness with hard work and drink. She stopped eating, and began to practice self-induced vomiting. The emission, she said, symbolised “Max, whom I had to eliminate if I wanted to live.” Though successful in repressing her failure to rescue Ernst, she became increasingly delusional, feeling an intimate connection to the earth, as though any of her actions could have terrible consequences for the world and its inhabitants. “My stomach was society.” She was twenty-three years old.

She escaped to Spain with friends, hoping, once there, to procure visas for herself and Ernst. Her suitcase bore, beneath her name, “a small brass plate set into the leather, on which was written the word REVELATION.”

…

Carrington’s memoir is about permeability, penetrability: the vulnerability of the body, matched by that of the mind. She insists on the kind of ‘body-writing’ later defined by Hélène Cixous as écriture féminine. It is in her moments of unreason that the two divide. “My anguish—my mind, if you prefer—was painfully trying to unite itself with my body,” she says of her mental state in Saint Martin. Unable to climb the mountain at France’s border with Spain, she questions her “mental balance”: vertigo will not allow her to proceed. “The illness of Madrid” also stems from the physical—her dysentery: “I convinced myself that Madrid was the world’s stomach and that I had been chosen for the task of restoring this digestive organ to health.” As she cleans herself obsessively, she becomes more certain that she has metaphysical power over the world. “I heard the vibrations of beings as clearly as voices—I understood from each particular vibration the attitude of each toward life, his degree of power, and his kindness or malevolence… As I looked into eyes, I knew the masters and the slaves and the (few) free men.”

What happens to the body, which is where the mind lives as indisputably, as inescapably, as a patient in a mental asylum, when the two become divided? In Madrid, she recalls, “[I] felt obliged to strip myself of everything.” Her self-abandonment in a cafe brings her to the attention of a group of right-wing Requeté officers, who take her to a hotel and gang-rape her. At the time, divorced from her body, she is unconcerned.

Carrington finds an uneasy ally in van Ghent, a politically dubious connection of her father’s. Promised her freedom, she is tricked, doped and “handed over like a cadaver to Dr. Morales, in Santander.” In the asylum, the doors are glass. She is watched; her body is bound. She is force fed—the stomach again—“I don’t remember anything about it.”

“For several days I had acted like various animals,” Carrington is told on regaining consciousness, recalling her personal identification with animals, and scenes of metamorphosis that occur in her pre-war stories and paintings. There, they represent avenues of escape; “here I was tied down like a wild beast.” On her way through France and Spain she had proposed “an agreement with the animals: horses, goats, birds”: magical thinking that might secure Ernst’s release. Once inside the asylum she talks ‘reasonably’, but acts like an animal—she describes fighting with orderlies and with other inmates, as well as “hanging batwise from the bars” by her feet. “You belong at court, or in a farmyard,” the asylum doctor tells her, and she falls in love with him. “So you feel better, Madmoiselle?… I am no longer seeing a tigress, but a young lady,” says a mysterious man in black who visits her after Cardiazol is administered as ‘convulsive therapy,’ the chemical precursor to ECT.

‘Convulsion’ is a Surrealist watchword: “beauty will be CONVULSIVE,” wrote André Breton, in Nadja, the book in which he describes his relationship with a young Russian artist, whom he abandons, and who ends up in an asylum.

Surrealism, born from the terrible psychological disjunctions of the First World War (Breton, served in the psychiatric wards of military hospitals), has no better home than in conflict. Surrealism’s interest in madness is not only psychological, but socio-political. In Surrealism and the Treatment of Mental Illness (1930), Breton declares that Surrealist works are designed to reveal the madness within ‘normality’, disturbing our understanding of ‘sanity’. Carrington’s escape from France is a Surrealist nightmare: reluctant to alert her friends’ attention to the coffins lining the roadside, which she believes may be an hallucination, only afterwards does she realise they might have come from Perpignan’s military hospital. In the asylum, she puzzles, “I tried understand where I was and why I was there. Was it a hospital or a concentration camp?”

For Carrington, the asylum becomes an ontological investigation of a new world, with the artist occupying a position somewhere between Robinson Crusoe and Gulliver, trying to excavate a system from her experience. Everything takes on a symbolic quality—“As for my Tangee lipstick, I have but a vague memory of its significance; it probably was the meeting with colour and speech, painting and literature: Art,”—but Carrington is always clear that the structures she imposes on the asylum while incarcerated are delusional: there is no system, and the inmates are no less sane than their keepers. One day, her nurse Frau Asegurado says, her doctor, Don Luis, “had gone mad.”

In Madrid, as in the asylum, Carrington is shepherded by male authority figures with whom she often establishes sexualised relations, and who betray her. “To me van Ghent was my father, my enemy, and the enemy of mankind; I was the only one who could vanquish him.” In the asylum, she seduces her doctor, who goes along with it, “aware of the power of Papa Carrington and his millions.” Whoever she fucks, it can’t not be her father.

The Surrealist patron, and supporter of Carrington’s work, Edward James, on meeting the artist in 1945, described her as “a ruthless English intellectual in revolt against all the hypocrisies of her homeland.” Down Below takes a turn toward surreal absurdity, as Carrington’s father dispatches her childhood nanny to liberate her from the Spanish asylum, with the aim of taking her to a more humane institution in South Africa. How does she escape this fate? By an illusion of conformity. She requests a trip to buy some ladylike protection for her hands in the South African sun: “Of course you must. Nobody goes out without gloves.”

Carrington, Self-Portrait aka The Inn of the Dawn Horse, ca. 1937-38

Obedience and disobedience are the subjects of the stories in The Oval Lady where the flipside of repression is lawlessness, and both are the children of unreason. Carrington’s European paintings draw on fairy tale, nursery objects, and the “lavatory gothic” of her family’s Crookhey Hall. Where male Surrealists often used images of women to allude to the unconscious in their work, Carrington frequently depicted animals. But for every Irish horse goddess in her early paintings, there is a rocking-horse. She later acknowledged, “We women allow ourselves to be devoured by our stuffed teddy bears,” Do You Know My Aunt Eliza? and I Am An Amateur of Velocipedes (both painted in 1941, when Leonora was in France) juxtapose polite titles with images that are both horrific and amusing, testifying to her shocking brand of parlour humour. They are the art of a rebellious occupant of the nursery, but in her Mexican paintings, the figures of women range across the whole house, and landscape, often much larger than life.

For the writer Ali Smith, Carrington’s art “asks questions about imprisonment and liberation.” Her escape from influential men—both ‘good’ and ‘bad’—was essential to her artistic development. In a coda to Down Below in 1987 she wrote:

What is terrible is that one’s anger is stifled. I never really go angry. I felt I didn’t really have to. I was tormented by the idea that I had to paint, and when I was away from Max… I painted immediately. I never saw my father again.

“After the experience of Down Below I changed. Dramatically. It was very much like having been dead,” Carrington told the writer Marina Warner in a 1987 interview. Carrington scholar Gloria Orenstein, who knew the artist, thought that in Down Below, “breakdown might be more accurately viewed as a breakthrough.”

Did Carrington find that her madness offered REVELATION? The Surrealist line holds that it should. In an issue of La Révolution surréaliste (1928), André Breton and Louis Aragon celebrate the “Fiftieth anniversary of hysteria.” Hysteria, they write, ”is a more or less irreducible mental condition, marked by the subversion, quite apart from any delirium-system, of the relations established between the subject and the moral world under whose authority he believes himself practically to be… Hysteria is by no means a pathological symptom and can in every way be considered a supreme form of expression.”

Carrington, The Pomps of the Subsoil, 1947

It has become an axiom that Surrealism, with its femme-enfant or intuitive (or even mad) ‘child-woman’ figure, whom Breton described a “conducteur merveilleusement magnetique”—a conduit between the (male) artist and the unconscious—was not fertile territory for creative women. However the number and variety of women practicing in and around the movement is often overlooked. This may be because they were seldom allowed to be involved in its mechanics—there was no woman signatory to either Surrealist manifesto—but, as with Freud’s writings, which were the movement’s bedrock, Surrealism’s engagement with creative women as muses and subject matter meant the movement had—if often unwillingly—to acknowledge the art produced by these 'femmes automatiques'. It is worth naming some of them here, as it is always with women, who are too easily otherwise tidied out of the view of history: Claude Cahun, Jacqueline Lambda, Remedios Varo, Katie Horna, Meret Oppenheim, Leonor Fini, Frida Kahlo, Alice Prin, Dorothea Tanning, Mimi Parent, Lee Miller, Dora Maar, Unica Zurn—in no particular order, and to name only a few.

In many ways, the pre-Down Below Carrington—beautiful, young, eccentric—appears to have had all the qualities of the conducteur merveilleusement magnetique. “Who is the Bride of the Wind?” asked Ernst in his preface to Carrington’s pre-war story, The House of Fear. “Can she read? Can she write in French without mistakes? What wood does she burn to keep warm?” Carrington’s stories of that era were, indeed, written in the erratic French of a non-native speaker, and perhaps this was a surrealist experiment in ‘automatic writing’, the pictured task of the femme-enfant in the Dictionnaire abrege du Surrealism (1938).

“I was never a Surrealist,” said Carrington. “I was just with Max.”But, while living with Ernst, besides painting and writing, Carrington became a performance artist of domestic Surrealism indulging in such stunts as serving guests with an omelette made from their own hair, cut while they slept. Like Meret Oppenheim, famous for her sexy fur teacup, Carrington was able to imbue domestic objects and processes with value, and power. Surrealism, with its interest in hasard objectif, and found objects, opened up art to the everyday (think of Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’), taking it out of the closed world of the male-dominated studio. With her friend and fellow-artist Remedios Varo, Carrington continued these experiments in domestic performance Surrealism in Mexico, inviting random strangers to dinner, picked blindly from the phone book in the manner of a proto-Sophie Calle.

Carrington’s European paintings show single, or paired figures: in the Mexico years her paintings become scenes of communal, not individual, identity, breaking with the folie à deux (or toute seule) scenes that populate the scenarios of European Surrealism. Following the turmoil of 1968 in Mexico, she was involved in founding the Women’s Liberation Movement in Mexico in the 1970s, believing that psychic and political liberation would go hand in hand.

Mujeres Conciencia: A poster designed by Carrington for Mexican women’s liberation

Carrington’s Mexican paintings show women living with women, going about the house, cooking, serving and eating, cleaning, each of these activities imbued with a feeling of wider significance. These are celebratory, ambiguous, nuanced pictures placing value on women's labour, and the complicated arts of domestic life.

Carrington, who claimed to have got on well with Breton, nevertheless called him ‘the headmaster’ behind his back. Her avoidance of complete adherence to any system or group is perhaps a woman Surrealist’s most sensible course. Carrington’s later iconography, drawn from Jewish, celtic, and Mexican myth, is not the Freudian symbolism of the European Surrealists, nor does she take a psychoanalytical approach to her breakdown in Down Below.

Down Below is not only a radical reworking of the Surrealist narrative of female madness: it is a sophisticated experiment with reason, subjectivity and the narrative voice, in which Carrington is able to speak clearly of madness from the outside, to speak clearly of what is within it, of its ins and outs, without committing wholly to memoir or to art (“I’m afraid I’m going to drift into fiction,” she tells her reader). She draws the reader toward herself, requiring her, or him, to meet her half-way: “I believe that I may be of use to you, just as I believe that you will be of help in my journey beyond that frontier by keeping me lucid…”

“I didn’t think of myself as a Surrealist,” Carrington repeats. “I try not to think of myself as anything.” Like later feminist theorists, including Luce Irigaray and Carol Gilligan, Carrington presents subjectivity as radically relational, codependent. In the asylum, she tells her doctor/jailer:

I have no delusions. I am playing. When will you stop playing with me? He would stare at me in amazement at finding me lucid, then laugh. And I would say: Who am I, while thinking: Who am I to you? He would leave without answering, completely disarmed.

Down Below is, sadly, currently out of print.

Joanna Walsh is a writer and illustrator, and is the author of Hotel, a Freudian memoir. Her other books include Fractals, and Vertigo. She writes criticism for the Guardian, the New Statesman, and the National (UAE) and is fiction editor at 3:AM Magazine. She also runs #readwomen, described by the New York Times as ‘a rallying cry for equal treatment for women writers’.