Staff picks: Feminist books for International Women’s Day

In celebration of International Women’s Day on 8th March, the women workers of Verso and New Left Review share some of our favourite feminist books in tribute to the radical roots of the observance.

- Jo Spence/Rosy Martin, Mother as Factory Worker, 1984-88

Essays, Criticism, Theory

Gender Trouble by Judith Butler (Routledge Critical Thinkers, 2006; 1990)

A classic work of gender and queer theory. Butler recently said in interview:

Gender Trouble was written about 24 years ago, and at that time I did not think well enough about trans issues. Some trans people thought that in claiming that gender is performative that I was saying that it is all a fiction, and that a person’s felt sense of gender was therefore “unreal.” That was never my intention. I sought to expand our sense of what gender realities could be. But I think I needed to pay more attention to what people feel, how the primary experience of the body is registered, and the quite urgent and legitimate demand to have those aspects of sex recognized and supported. I did not mean to argue that gender is fluid and changeable (mine certainly is not). I only meant to say that we should all have greater freedoms to define and pursue our lives without pathologization, de-realization, harassment, threats of violence, violence, and criminalization. I join in the struggle to realize such a world.

Love for Sale: Courting, Treating and Prostitution in New York City, 1900-1945 by Elizabeth Alice Clement (University of North Carolina Press, 2006)

A fascinating materialist history of dating, and the economics of dining out, evening entertainment, dresses, stockings, and more. Clement explores the history of “treating” in industrializing New York City in which working-class women now employed at shops and factories during the day informally paired off with men to afford nightlife fun in (implicit or explicit) exchange for sexual relationships.

Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement by Angela Y. Davis (Haymarket Books, 2016)

In this collection of essays, interviews, and speeches, Angela Davis reflects on the importance of Black feminism, intersectionality, and prison abolitionism for today’s struggles, and analyzes struggles against state terror, from Ferguson to Palestine.

Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle by Silvia Federici (PM Press, 2012)

Written between 1974 and 2012, the essays collected in this volume represent forty years of research and theorizing on questions of social reproduction and the transformations which the globalization process has produced. Starting from Federici’s incendiary writing around the Wages For Housework movement, the range broadens out to the international restructuring of reproductive labour, the globalization of care work and sex work.

Leftover Women by Leta Hong Fincher (Zed Books, 2014)

Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China is a a compelling and innovative sociological enquiry into the political economy of gender in contemporary China.

Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work by Melissa Gira Grant (Verso, 2014)

“To insist that sex workers only deserve rights at work if they have fun, if they love it, if they feel empowered by it is exactly backward. It’s a demand that ensures they never will.” Melissa Gira Grant

A political critique that takes sex work out from under its usual autobiographical (and voyeuristic) lens, Playing the Whore situates it firmly as a form of labour that demands political attention. Holding the media to account for perpetuating some of the most harmful myths about sex work and sex workers rights, Gira Grant argues that separating sex work from the "legitimate" economy only harms those who perform sexual labour.

The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling by Arlie Hoschchild (University of California Press, 2012)

A landmark examination of gendered emotional labour of pink-collar service workers and the instrumentalization of our emotions in the world of work. Emotional labour, Hoshchild argues, alienates us from our feelings and estranges us from our expressions of feeling, like a manual worker who becomes estranged from what he or she makes.

Read more about emotional labour: Love’s Labour’s Cost: The Political Economy of Intimacy By Emma Dowling

Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde (Ten Speed Press, 2014)

Sister Outsider is an absolutely essential collection of fifteen essays and speeches from 1976 to 1984 including and the origin of the “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Audre Lorde, both the ‘sister’ and ‘outsider’ of the title, explores the complexities of identity, drawing from her personal experiences with oppression, including sexism, heterosexism, racism, homophobia, classism, and ageism. In response to the tendency of mainstream feminism to deny difference between women, thus replicating hierarchies where the most privileged dominate, Lorde argues that difference—and the anger of the oppressed—can be productive for liberation. Sister Outsider presents groundbreaking work that is strikingly relevant today, and is all the more valuable for challenging its readers to question and scrutinize their own complicity in structures of oppression and the privilege that blinds them.

Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, ed. by Katherine McKittrick (Duke University Press, 2014)

Katherine McKittrick spills open Jamaican writer and cultural theorist Sylvia Wynter’s inquiring body of work. Wynter’s decolonial, radically futuristic writing interrogates the exclusive category of “human” and provides blueprints for how to dismantle white supremacy

This Bridge Called My Back, ed. by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa (SUNY Press, 2015)

Arguably one of the most influential feminist anthologies ever published, and deservedly. Originally released in 1981, This Bridge Called My Back is a testimony to women of colour feminism as it emerged in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Through personal essays, criticism, interviews, testimonials, poetry, and visual art, the collection explores, as coeditor Cherríe Moraga writes, “the complex confluence of identities—race, class, gender, and sexuality—systemic to women of color oppression and liberation.”

As Angela Y. Davis writes: “This Bridge Called My Back … dispels all doubt about the power of a single text to radically transform the terrain of our theory and practice. Twenty years after its publication, we can now see how it helped to untether the production of knowledge from its disciplinary anchors—and not only in the field of women’s studies. This Bridge has allowed us to define the promise of research on race, gender, class and sexuality as profoundly linked to collaboration and coalition-building. And perhaps most important, it has offered us strategies for transformative political practice that are as valid today as they were two decades ago.”

Woman’s Estate by Juliet Mitchell (Verso, 2014; 1971)

Combining the energy of the early seventies feminist movement with the perceptive analyses of the trained theorist, Woman’s Estate is one of the most influential socialist feminist statements of its time. Scrutinizing the political background of the movement, its sources and its common ground with other radical manifestations of the sixties, Woman’s Estate describes the organization of women’s liberation in Western Europe and America. In this foundational text, Mitchell locates the areas of women’s oppression in four key areas: work, reproduction, sexuality and the socialization of children. Through a close study of the modern family and a re-evaluation of Freud’s work in this field, Mitchell paints a detailed picture of patriarchy in action.

Read more: Looking back at Woman’s Estate

Juliet Mitchell reflects on how the joy and practical experience afforded by Women's Liberation—and its tensions with other protest movements of the time—inflected the writing of her book in 1969-1970.

Angry Women (RE/Search publications, 1991)

In this illustrated, interview-format volume, 16 women performance artists animatedly address the volatile issues of male domination, feminism, race and denial. Among the modern warriors here are Diamanda Galás, a composer of ritualistic "plague masses" about AIDS who refuses to tolerate pity or weakness; Lydia Lunch, a self-described "instigator" who explains that her graphic portrayals of exploitation stem from her victimization as a child; and Wanda Coleman, a poet who rages against racism and ignorance. Goddess worshipper and former porn star Annie Sprinkle enthusiastically promotes positive sexual attitudes; bell hooks eloquently discusses societal power structures in terms of race and gender; Holly Hughes, Sapphire and Susie Bright expound on lesbianism and oppression; pro-choice advocates Suzy Kerr and Dianne Malley describe their struggles for reproductive rights.

Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty by Dorothy Roberts (Vintage, 2000; 1997)

A necessary biopolitical history of systematic reproductive violence against Black women in the US, both legal and social — the reproductive “property” of women in slavery, the ties between the early birth control and the eugenics movements, welfare, and the race and class implications of reproductive technology new and old.

Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality by Anne Fausto Sterling (Basic Books, 2000)

Fausto-Sterling is a biologist who explores the social construction of gender to show not simply the truism that gender is a separate category from biological sex, but more importantly that the science behind what is known as "biological sex" is already constructed in a historically politicized context so that there is much more physiological fluidity and variety and source of definition than typically acknowledged. An important history of intersexuality as well as technology and medical intervention.

Memoir

A Small Place by Jamaica Kincaid (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000; 1988)

In this short memoir Kincaid welcomes you to Antigua, her home. You, the well-meaning but ignorant tourist arrive on her island and are shown the sights of an island that is "too beautiful" in a way that seems "unreal", particularly when seen in contrast to its current state of poverty and dilapidation, and history of slavery. First published in 1988, A Small Place is an angry autobiography that challenges its reader to reconsider the behaviour of the tourist as well as more broadly considering the role of the coloniser in a stark and often unusual way.

Disavowals by Claude Cahun (Tate Publishing, 2008)

A brilliant book of 'cancelled confessions' based on Cahun's 1930 book Aveux non avenues, Disavowals is the first English translation of her writings. Throughout the book she explores ideas around gender-bending, humour, narcissism the self and sexuality; using photomontage and statement Cahun presents herself as resistant to identification itself, instead maintaining "the mania of the exception."

King Kong Theory by Virginie Despentes (Serpent’s Tail, 2009)

Charting Despentes' journey through poverty, rape, sex work, pornography and then fame as the director of Baise-Moi, it’s a furious, polemic-come-memoir as provocative and contentious as it is illuminating. Feminist fire for the soul.

Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More by Janet Mock (Atria Books, 2014)

Janet Mock’s memoir, Redefining Realness defines her womanhood as a journey too vast and expansive to be limited by biological essentialism. Mock’s womanhood is self-determined and powerful; cultivated through community, third gender traditions such as Hawaii’s Māhū, blackness, and the cultural impressions of Destiny’s Child and Janet Jackson.

Love's Work by Gillian Rose (NYRB Classics, 2011)

Written in the months preceding her untimely death at the age of 48, Love's Work offers up the richest autobiographical details of Rose's life, focusing on several friendships and love affairs, as well as her fiercely intelligent relationship with the study of philosophy. Love, for Rose, is merciful and important but never eternal, requiring the hard work of the mind and body for sustenance. This is a book for anyone with an interest in the qualities and connections between love, death and learning.

Promise of a Dream: Remembering the Sixties by Sheila Rowbotham (Verso, 2001)

A moving and funny account of a blossoming feminist consciousness during the 1960s by the pioneering feminist historian and activist. Sheila Rowbotham's memoir is a feminist bildungsroman threading together the films, books and memories created by women that influenced her. Set in the exhilarating sixties, Promise of a Dream portrays the idealism and the ambiguity of the era, including the deep-rooted sexism of the New Left and the hippies.

Read more:

- Looking back at Woman’s Consciousness, Man’s World: Rowbotham looks back at the world of Woman’s Consciousness, Man’s World's birth in the Women's Liberation movement, as she sought to situate her feminist politics in relation to the changing shape of capitalism to forge a new way to describe the interaction between inner perceptions and external material life.

- Looking back at Women, Resistance and Revolution

Women, Resistance and Revolution was Rowbotham's first book written in the summer of 1969 when she was 26.

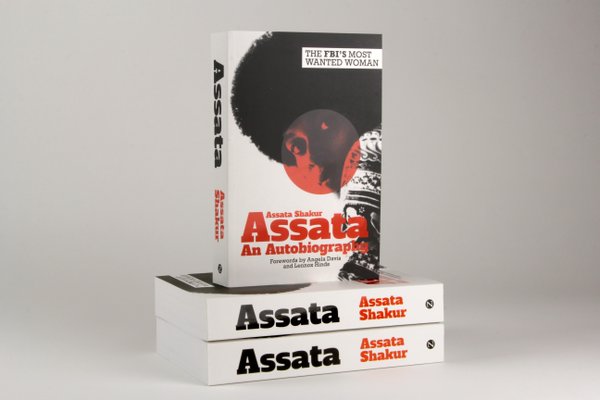

Assata: An Autobiography by Assata Shakur (Zed Books, 2014)

A leading figure in the 70s Black Liberation Army, Assata Shakur was placed on the FBI Most Wanted Terrorists list in 2013, 40 years after she received a life sentence for killing a New Jersey state trooper in 1973, and nearly three decades after she escaped prison and was offered political asylum in Cuba.

This courageous autobiography explores her childhood and political activism, as well as the endemic racism and abuse she experienced in the American prison system, her many legal battles, and American civil rights.

Fiction

Sitt Marie Rose by Etel Adnan (Post Apollo Press, 1973)

Etel Adnan’s poetic novel takes place in Beirut during the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. Sitt Marie Rose, a Christian fighting for Palestinian liberation, embodies Adnan’s dream of a feminist anti-war movement.

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler (Headline, 2014; 1979)

Black feminist science fiction writer Octavia Butler’s Kindred is simply devastating. In this genre-bending novel of speculative fiction, time travel transports a self-possessed and strong woman protagonist between 1976 and an early 19th century Maryland plantation for a nuanced, gripping and complex portrayal of the effects of chattel slavery on generations.

The Hearing Trumpet by Leonora Carrington (Penguin, 2005)

The Hearing Trumpet is British-born Surrealist Leonora Carrington’s best-known work written in the 1960s and first published in 1974. This riotous novel is full of rebellious joy in the trailblazing feminist magical realist vein of Carrington’s artistic practice. Deaf, bearded Marian Leatherby, 92 years old, has been committed to an institution for the elderly where another resident gives her a forbidden book recounting the secret life of a great woman. The surreal adventures that unfold with a delightful coterie of witchy women have rightfully earned this book a place in the subversive, anti-institutional feminist pantheon.

Read more: "I have no delusions. I am playing"—Leonora Carrington's Madness and Art

Joanna Walsh examines the intertwining of madness and art in surrealism and how Carrington refused the surrealist romanticisation of female madness, describing her time in the Spanish asylum in terms of a forced incarceration. Through her life and work, Walsh traces Carrington's rejection of patriarchal authority through her political activism and through the creation of dreams, myths and symbols centred around the feminine in her art.

The Lover by Marguerite Duras (Pantheon, 1985)

The Lover draws on a love affair between the 15 year-old Duras and a wealthy older Chinese man. Set in Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh, Duras’s luminous novella is a deceptively simple exploration of the complexities of race, gender and class told through the eyes of a nameless ‘I’ from an impoverished colonial family with a widowed and mentally unwell mother and a bullying brother. Enchanting and heartbreaking, this representation of an illicit affair is also a provocation to the constructed palace of memory: Duras would write the story over and over again in her lifetime, completing The Lover aged 70. Born in Indochina, Duras left for France at the age of 17 where she was to become involved in the Resistance (while working for the Vichy government) and the PCF, from which she was expelled. Awarded the Prix Goncourt in 1984.

The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante, translated by Ann Goldstein (Europa, 2005)

As in all of Ferrante’s brilliant books, Days of Abandonment strikes right at the heart of the quotidian misery of domestic life. Intensely claustrophobic, and claustrophobically intense, it follows the near-breakdown of a woman whose husband leaves without warning. Set almost entirely within the walls of her apartment, it is an almost unbearable confrontation with the pressures and resentments of motherhood, grief and sexuality. Visceral, dizzying, terrifying—this slim book does more in 192 pages than most in double that.

Airless Spaces by Shulamith Firestone (MIT Press, 1998)

Airless Spaces comprises Firestone's first collection of fiction—stark, sad and sometimes sly short stories about "airless spaces": mental illness and the institutions that seek to contain and cure it. The author of the feminist classic The Dialectic of Sex (Verso, 2015) paints compelling portraits of those in mental hospital, precarious lives after hospital, "losers", suicides and obituaries of people she knew, including Valerie Solanas.

The Piano Teacher by Elfriede Jelinek (Serpents Tail, 1983)Michael Haneke made a beautiful and stark film from this novel, homing in on the mother-daughter power dynamics at the heart of the story, but in the adaptation he necessarily lost much of what makes this novel so brutally intense – its setting in the haute-bourgeois Viennese music conservatory, the linguistic experimentation that boils over with a feminist rage. Preoccupied in everything she does with the social division of power, Jelinek writes unflinchingly about sex, a perfect antidote to all those Bellow and Roth sex scenes you’ve had to endure.

The Tombs of Atuan (Earthsea Cycle) by Ursula K. Le Guin (Atheneum, 2012; 1971)

Set in the Place of Tombs, a society of women and eunuchs, The Tombs of Atuan follows the life of Tenar, renamed Arha (the eaten one) after she is made high priestess to the Nameless One. She is confined to the underground labyrinth temple, where light is forbidden and no one but her is permitted to enter. However, when she captures and holds prisoner the wizard Sparrowhawk (of the previous Earthsea book) who is trespassing in the labyrinth she begins to question the fierce structures of her dark world.

A Girl is a Half-formed Thing by Eimear McBride (Faber & Faber, 2014)

"The answer to every single question is Fuck."

The uncompromising, fragmented prose in this outstanding novel unravels a relentless story of Irish girlhood; full of emotional betrayals, physical abuse, and staggering twists that will have you gasping for air.

That man was sterner stuff than us. A right hook of a look in his eye all the time. Thin tight gelled hair. Moustache brown eyes. Clark Gable-alike when he was young, she said. But every man was I think then, when she was growing up. Under the thumb of him. Under his hand. Movie star father with his fifteen young. His poor Carole Lombard fucked into the ground. Though we don’t say those words. To each other. Yet. They were true God fearing in for a penny in for a pound. Saturday til afternoon dedicated for praying with his wife – when none of the little could enter without a big knock. Such worshipping worshipping behind the bedroom door. With their babies and babies lining up the stairs. For mother of perpetual suffering prolapsed to hysterectomied. A life spent pushing insides out for it displeased Jesus to give that up. Twenty years in bed and a few after this before she conked.

The Voyage in the Dark by Jean Rhys (Penguin, 2000; 1934)

In depicting the disturbing journey from the Dominican periphery to the heart of empire, The Voyage Out turns Conrad’s Heart of Darkness on its head. Rhys depicts London in all its brutality – its deep class-structures, casual cruelty and grey banality. As with all her novels, this takes the vantage point of the dispossessed, women locked-out, caught somewhere in an ambiguous zone verging on prostitution. Deceptively unremarkable sentences capture the captivity of women, and the longing, rage and desperation to be free.

Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi, translated by Sherif Hetata, and foreword by Miriam Cooke (Zed Books, 2015; 1975)

Reissued by Zed Books this year as part of a gorgeous set of three new editions, this classic feminist work is still as powerful, relevant, and compelling as ever. Described as a “blood-curdling indictment of patriarchal society” by the Guardian, is it easy to see within just a couple of pages why Nawal El Saadawi is one of the most influential feminist thinkers in the Arab world. What’s harder to understand is why she has been left out of the western feminist literary canon for so long.

The Man Who Loved Children by Christina Stead (Capuchin, 2010; Simon and Schuster, 2010; 1940)

The eponymous man of this novel is NOT a paedophile, he’s an arch-idealist bureaucrat in Washington who subjects his family and his writer-to-be daughter to the same chipper narcissism as he does his all-American fellow-patriots. It’s a reign of terror. This book operates at such a pitch of psychological violence to have you gasping for air, and rooting for Louie’s escape.

>> see also: our Verso International Women's Day reading, 40% off until March 9th!