Rebuilding After Coronavirus

'For all the lab work and vaccine hunts, it is ultimately society itself that pandemics put under the microscope.'

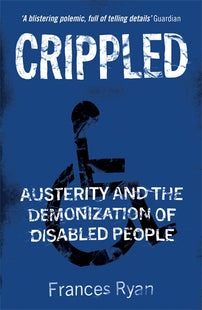

Frances Ryan addresses the political and social impact of coronavirus in this extract from the new conclusion to Crippled, available from the 1st September 2020 from Verso.

In the spring of 2020, as the UK’s coronavirus lockdown began, 500,000 volunteers signed up to the NHS to give their time to those in need. It was an army of helpers, doing everything from driving people to hospital appointments to dropping off food parcels to the isolated. This was on top of informal, local mutual aid groups that sprung up all over the nation in a bid to reach people with a disability, as well as the elderly, who were forced to self-isolate to protect themselves from the virus. This volunteerism in many ways reflected a trend that has come to define so much of the austerity era, where food banks and community groups have been left to patch up the holes left by a shrinking government.

Yet what was fascinating about the response to the corona- virus was how mutual aid was accompanied by something else: the growth of the state. Established truths were suddenly turned on their head. With businesses forced to close, billions of pounds of loans were offered to bosses while employees who couldn’t get to work were granted 80 per cent of their wages. Private landlords were banned from evicting tenants during the crisis, while local authorities in England started housing all rough sleepers – as if it had been possible all along. Middle-class professionals suddenly found themselves reliant on the social security system as nearly a million people applied for universal credit after being made jobless from the lockdown.

A global pandemic had forced Britain’s small state Conservative party to opt for mass intervention. The sort of large-scale investment formerly dismissed as a ‘magic money tree’ or dangerously ‘Marxist’ was now common-sense pragmatism. The deep cuts to public services and squeezes on wages were, it seemed, a political choice after all.

It was not only our relationship with institutions that changed during the coronavirus crisis but how we viewed the people in them. Low-waged supermarket workers and care staff previously dismissed as unskilled and unimportant were suddenly the heroes of the hour, while ministers who had formerly starved hospitals of funds found themselves clapping NHS staff along with a grateful nation.

For all the lab work and vaccine hunts, it is ultimately society itself that pandemics put under the microscope. Where does power sit? What is the role of the state? When the crunch comes, are we protected? The coronavirus, for its part, laid bare the frailty of Britain’s social contract after a decade of cuts – public services that had been starved of funding, millions of people in insecure and low-paid work, and a social security system unfit for purpose. In turn, it shone a light on some long-ignored truths: universal healthcare is a non-negotiable good; workers dismissed as unskilled are actually the ones who keep us alive; public services are precious resources to be invested in for hard times; each of our lives is more dependent on others than we may think.

Perhaps few areas showed this more than the welfare state. If Crippled outlined what can happen when the safety net is devalued and shredded, the coronavirus pandemic was an unforgiving reminder of why it need be valued and protected. The pandemic fallout quickly exposed the myths at the heart of government cuts in recent years: that the welfare state is not actually a drain or a burden but a precious form of collective insurance against life’s challenges, be it ill health, disability, or unemployment. As the writer Peter C. Baker put it on life after coronavirus, ‘Disasters and emergencies do not just throw light on the world as it is. They also rip open the fabric of normality. Through the hole that opens up, we glimpse possibilities of other worlds.’

We have already seen such glimpses. They are there in the public’s newfound respect for the lowest paid who have fed and nursed them through a pandemic. It is there in a right- wing government forced to invest in public services, provide income for the sick and unemployed, and house the homeless. It is there in the general population beginning to view social security as something no longer just for ‘other people’. Or to put it another way: it is there not in the crisis, but in how we choose to rebuild after it.

The task for the Left going forward is to ensure the transformative actions we have witnessed are not temporary, but a turning point that long outlives the immediate crisis. The drastic measures governments have taken in recent months, not only in Britain but around the world, are evidence of just how much the state can accomplish – that there is really no limit to the changes that can be made, or the interven- tions that can be waged, if there is sufficient public demand for it. To return to a key sentiment of this book: where we are is surely not the best we can do.

The coming years will undeniably present great challenges to Britain as we are set to fight on three fronts. Brexit remains a great uncertainty squarely focused on the marginalized as any economic impact will inevitably hit the poorest. The coronavirus likely risks creating a recession of its own, all while the nation’s infrastructure from libraries to social care must recover from a decade of austerity. This is on top of the juggernauts of the climate crisis and rampant economic inequality that our global neighbours face with us.

And yet out of the ashes can rise more than a flicker of light. Improved sick leave. Higher wages for care workers. Greater empathy for the disabled and ill. A culture of collectivism based on our interdependence. Strengthened and newly respected social security. The possibilities for progress are in many ways endless, only limited by the scale of our own vision. Those of us with egalitarian ideals in Britain are now tasked with some of the greatest challenges we could imagine, but with each challenge comes a chance for change.

The dark era in which we find ourselves does not mean only that a vision of hope and ambition is still possible for the left – it is more important than ever. We can achieve it, together.

Nottingham, May 2020

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]