Gaza: how far can their patience be stretched?

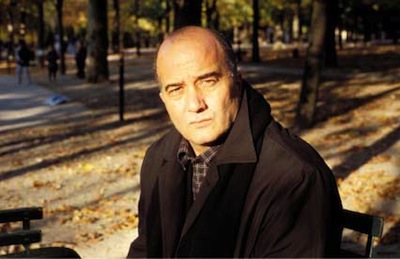

By Christian Salmon

18 July 2014

In April 2002 we crossed Palestine from Ramallah to Gaza together with other writers from the International Parliament of Writers. Upon my return I wrote this eyewitness account of this war without end: a war waged with tanks and bombs but also with bulldozers. A work of demolition. An effort at re-territorialisation without precedent in history. An agoraphobic war…

The text was entitled ‘Sabreen, or patience’. More than ten years later, I would add: how far can their patience be stretched?

In the period of the Yugoslav wars the architect Bogdan Bogdanovich coined the term ‘urbicide’ to refer to the destruction of Balkan towns. What is immediately striking in Palestine is the violence carried out against land, against territory. Everywhere you see nothing but construction sites, deforestation, hills that have been cut open: landscapes that have been ruined, made unreadable by an apparently concerted violence. Not only the violence of bombs and war, not the destruction inflicted by the tank incursions – the most modern and heaviest tanks in the world – but an active, diligent, industrious violence. The ugliness of concrete and asphalt spreads throughout the most beautiful landscapes of human history. The hills are lacerated by ‘bypasses’ built in order to protect the access routes to Israeli settlements; in the surrounding area they knock down houses, uproot olive groves and tear down orchards… to improve… visibility. Spreading in their place are wastelands, a no man’s land surveyed by watchtowers. The bulldozers that you see everywhere along the roadsides appear to be just as strategically important in the ongoing war as are the tanks. Never has such an innocuous machine seemed to me to be the bearer of such quite violence. Geography, it is said, serves first of all for making war. In Palestine, it is war that is taking over geography.

Across the course of a week spent travelling from Ramallah to Gaza and Rafah all we came across were images of destruction: villages, roads, and houses in ruins: they burned crops and bombarded public services. Infrastructure that had hardly been finished was destroyed by missile fire coming from F16s or helicopters: for example Gaza’s port and international airport, the Ramallah radio station Voice of Palestine, a traffic management headquarters, a medical-legal research centre, municipal infrastructure: schools, homes, roads, sewage systems, waste facilities. Who is going to believe that all of these places were terrorists’ hangouts?

In Rafah we visited a village on the Egyptian border that had been razed to the ground; we walked on the walls of the houses that had been knocked down. Under our feet there were school exercise books, kitchen utensils, a toothbrush. The leftovers of human life. A woman explained to us that the inhabitants had been given five minutes’ warning to get out. In the middle of the night. The bulldozers came back several times to ‘finish off the job’, a formulation which seems to be becoming the IDF’s new motto. Up above the watchtowers, infra-red machine guns watch over a wasteland. Yet there are no soldiers. At night they fire automatically whenever someone turns on a light. The first rows of houses are riddled with bullets. The inhabitants live under the constant threat of automatic weapons. That is how buffer zones are set up.

The destructive machine is constantly at work, patient and single-minded like a bee. What is it doing? It is making the border. It spreads the border. It border-ises everything. Here the border is everywhere. It runs through every street corner, every hill, every village and sometimes every house… Fortifications are replacing olive groves. Fortifications strengthen the ramparts. Every wall is hostile. Any house could be shadowing a hidden gunman. A checkpoint could be set up on any corner. We passed through two checkpoints two hundred metres. The West Bank alone today counts more than seven hundred of them. Certain streets have been blocked off by walls, and access to the Bir Zeit University demands using a double bus or taxi route, a journey split in half by a compulsory stretch on foot. The Israeli army has transformed the occupied territories into a system of honeycombs to which it controls the entrances and exits. There are some 220 of these, real mousetraps – if not ghettoes or reservations – in which Merkava tanks are constantly on patrol and Apache helicopters supplied by the US Army circulate overhead… It is a border of a new kind. A mobile, porous, fluid border. A border that moves. One evening in Ramallah, Marmoud Darwish had us go up a small hill from which we could see Jerusalem. A few kilometres away as the crow flies, the city shone with thousands of lights. Between it and us stood shadowed areas with a handful of flickering lamps: Palestinian houses, then further across on the right, another area of intense light, where there began an empty lit road leading to an Israeli settlement. And as these lamps glimmered in the night, I recognised that what was shining was, in fact, the border.

The Polish writer Konwicki once said of his own country that ‘my homeland is on rollers; its borders shift with every treaty’. In Palestine it is even worse. The border moves like a cloud of locusts. With each suicide attack, the border leaps forth with the suddenness of a lightning strike. It could arrive at your house in the morning like the postman, yet with the speed of tanks… or slowly come up on you like a shadow. The border crawls forward. It encircles villages and water sources. It moves with the erection of fortification walls, bracketed together as we saw in Rafah, walls that can be moved at the whim of the advancing colonisation, just like shifting the partitions between cubicles in an office.

The border is stealthy: the very image of the bombers, it shatters and destroys space. It transforms it into border-space, mere crumbs of territory. The border-space does not organise the flows of traffic, but paralyses them. Nor does it protect people, but transforms the whole space into a minefield, and every individual into a live target or a human bomb. The border here is no longer the kind of peaceful boundary that distinguishes between spaces of sovereignty, giving each its rightful place, giving space these shapes, these edges, these colours. Instead, it expels, it displaces, it disorganises… whether you are in Israel or the occupied territories, space has become hostile, a space without content or contours, making insecurity a generalised condition. ‘Eliminating distance kills’, René Char once wrote.

Windows turned into slits for guns, building façades made into ramparts, the close alignment of apartment blocks, barrack-towns… what you see in the Israeli settlements suggests an architecture closed in on itself, a self-enclosure that is evidently due to security constraints but also speaks to an obsession with space, with the dreaded space that must be walled off, the space of fear. ‘The truth of an epoch’ Hermann Broch said with regard to late nineteenth century Vienna, ‘may generally be seen in its architectural façade’. If that is true, then the set-up of the Israeli settlements is like a slogan expressing their panic with regard to their surroundings, a fear of the outside world, the opposite of welcoming hospitality. It is a sort of exophobia, the occupation process turned inside-out. The more they advance into enemy territory, the more they are closed in on themselves. This goes for all of Israeli society. Not the exo-colonialism evoked by the outward-looking Spanish architecture in Latin America. This is endo-colonialism, an inward-looking variety that does not just seek to appropriate a hostile space, but represents a dispossession of the self. Its ideal type is the bunker.

This is an aspect of the situation that political and media debate has largely passed over in silence: the Israeli colonisation of the occupied territories is not only unjust and illegal, but is also impossible; it is based on the inability to live that is characteristic of exile pathologies and which also afflicts the inhabitants of refugee camps. The Israeli settlements are, truth be told, uninhabitable. Not simply uncomfortable or dangerous or unviable in the long term. They expose the impossibility of ‘returning’ to inhabit somewhere. Hence its paradoxical forms. An overstretched, literally extravagant habitat. The security of each settlement in the heart of majority Palestinian areas (50,000 settlers as against 1.5 million Palestinians in Gaza alone) demands constant security measures, the total mastery of entrances and exits; each time a settler’s car passes it provokes traffic jams several kilometres long on the adjacent roads blocked by checkpoints. It is a sort of road-going apartheid placing ever more demands on the population. In Gaza, where the settlers are fewer in number and the abandonment of the settlements seems more likely, we saw roads separated by two-metre high walls, where a bridge is being built to join together the occupied land. The omnipresent bulldozers by the roadside are the troubling testament to this; the central question is not the one that Kafka posed, ‘how can we live?’, since the objective here is not living, but displacing.

In a few decades the Israelis have gone from the utopia of the kibbutzim to the a-topia of the settlements. People said in the 1960s, when the kibbutzim project still had some appeal, that they wanted to transform the desert into a garden. Yet they transformed the Biblical garden into a desert, a no man’s land – or rather, a battlefield. It is a war waged with bulldozers. A work of demolition. An effort at re-territorialisation without precedent in history. An agoraphobic ward. Movement between Israel and the occupied territories is totally blocked. Mahmoud Darwish has not been able to go to Israel since the burial ago of his friend Emile Habiby, the novelist and Knesset member; three years ago, he was not even able to visit his mother in hospital, as his presence in Israel was considered to be a threat to its security. Countless other Palestinian writers complained to us about this house arrest. Palestinian children will never set foot in Israel, and know nothing of this hostile country except for the armed soldiers who knock down their houses and humiliate their parents in front of them. Having become adults, they will know nothing of Israel except the bombers rumbling through the skies, the Apache helicopters that spit their fiery venom on their schools and cultural centres, or the bulldozers that raze their villages to the ground… On the other side, the Israelis only know Palestinians as the kamikazes who blow themselves up in cafés. Meetings between Israeli and Palestinian writers have become impossible, because of the restrictions on movement.

But this difficulty also exists among the Palestinians. It is impossible to go from Ramallah to Gaza. To get from one point of the Gaza Strip to another, a Palestinian writer told us, may well take more time than it would take to go to New York. They do not see each other any more, read each other any more, speak to each other any more. A troubling silence is spreading across all of Palestine. On one side and the other of the invisible border, words no longer seem to refer to the same things. Certain things cannot even be named any more. The figure of the Palestinian kamikaze occupies the Israeli imaginary, whereas the Israeli occupier muzzles Palestine’s future.

Two days after our departure, the Israeli army went into Ramallah. It again occupied all the public buildings and posted snipers in the upper floors of the apartment blocks in order to shoot at passers-by like the Serbs did in Sarajevo, bombarded the blocks where civilians had taken refuge, and violated religious sanctuaries that had served as refuges since the Middle Ages. But worst of all: having seized control of a private TV station it interrupted all the programming and without even addressing itself to the viewers, began showing pornographic films!

Is that the image of the free world that Sharon pretends to incarnate? An army of occupation that commits such acts has clearly lost any legitimacy; it represents nothing more than the power to humiliate. Worse for him, colonial history has many times shown that this is not how you win a war… of course, however, they want to convince us that this war is not a war, but an exercise in self-defence! That the destruction of all the civilian infrastructure of the future Palestinian state is an anti-terrorism measure! That the invasion of a sovereign territory is not an occupation. There is not just a walling off of territory – an insult to the future – but also a rhetorical shutdown. Language has become powerless. Palestine is the land where language is torn apart. I particularly remember seeing a Palestinian poet at the Ramallah cultural centre who spoke about the war’s doleful impact on… syntax! ‘War has made our language sclerotic. Poetry has been broken even more than our streets. We are constantly forced to dramatise poetry. We must resist this military metre, and find a cadence other than that of the war-drums’. He then concluded with weary irony: ‘When we look up at the stars, we see helicopters. The only postmodern thing here to be found… is the Israeli army!’ And I thought of Darwish’s courageous statement a few months ago, ‘I will only ever be truly free when my people is free. When I am freed of Palestine’. I am astonished that Palestinians have preserved this freedom even amidst the war, this honest relationship toward themselves and their language. The resistance of language, more than the language of Resistance. A few days later I heard the Israeli historian Amnon Raz, who is opposed to Sharon’s policy, expressing the same view in Tel Aviv: ‘Since the failure of the Camp David talks we have no vocabulary left. In order to negotiate, in order to be able to make peace, we need a new language’. And Arthur Koestler once said the same thing: ‘Wars are waged over words, on the terrain of semantics’. Today, the logic of war dominates debate. That is why writers are needed. Not to play at blue helmets, but to listen and make other voices heard, the voices of writers, artists, academics, all those who are preparing the future outside of party lines. All together they can oppose the logic of war, counterposing to this not a force of ‘inter-position’ but rather forces of ‘inter-pretation’. Their role, which is immense and yet at the same time limited, consists of breaking the silence and again starting to say what is going on. They must rebuild a language of peace. Peace is always a new language, a different logic, another syntax. That is what we spoke about with Israeli and Palestinian writers.

The Israeli army went into Ramallah just after we had departed it, sacking and destroying the Kassaba theatre which had just a few days previously still reverberated with the echoes of our texts read out in eight languages – from Chinese to Arabic, Afrikaans to English, Yoruba to Portuguese, to Italian, Spanish and French – and in which Mahmoud Darwish had read his poem State of Siege in front of a thousand spectators. Some among this audience had been travelling for several hours on account of the military controls, and they stood to cheer not religious fanatics full of hatred, nor even armed fighters for the Palestinian cause, but writers and poets. I understood that what divides these two peoples is that while the Palestinians still do not have a state or a territory, they do have a narrative, which is precisely what the State of Israel – which oppresses and humiliates, sacks and pillages – is now losing.

Narrative authority. Not the political authority that Sharon and his successors can hope for some time to continue to impose through tanks and bombs, but the authority of the spoken story. You can be a people without a state or land of its own, but you cannot long remain a people without a story. That is what I learned in Palestine. And this lesson has a name: Sabreen. I did not find this word in a book or a dictionary, but discovered it in the streets of Ramallah, on the roads of Gaza and Rafah, on the faces of the workers I saw crowding at the checkpoints and who waited for hours to get back home in the evening. Sabreen. It is not a word full of hatred. Sabreen is the dignity of pregnant women sat by the roadside. Sabreen is the joyful spirit of the students who each day walk the paths broken up by tank tracks, in order to get to Bir Zeit university. Sabreen is the tenacity of the women who wearily point to the broken partitions between their dwellings in the Al Amari refugee camps. Sabreen means ‘people who show patience’. And I said that evening at the theatre in Ramallah – today destroyed, plunged into silence and darkness – ‘it is because you are patient that the future belongs to you’.

Translated from french by David Bröder.

See the original french here.

See more from Christian Salmon here.