The Beginning of the End

An excerpt from Angelo Quatttrocchi's lyrical eyewitness account of May 1968 in Paris.

First published in Autumn 1968 — and reissued by Verso in 1998 — The Beginning of the End is one of the earliest, most urgent accounts on the May events in France. Written in two parts, the first is an eye-witness rendering of "what happened" in the form of a lyrical prose-poem by Angelo Quatttrocchi; the second a Gramscian analysis of "why it happened" by Tom Nairn. "The two pieces," Tariq Ali writes in his introduction to the Verso edition, "are different in tone and style, but not in temper. A volcanic passion underlies them both, a passion that expresses hope and optimism for the future. We were all convinced that the French May heralded a new order."

Below, we present the prelude and the first two chapters of Quattrocchi's section of the book, which describe the first stirrings of the new student movement at Nanterre and the developments of May 3rd, when a student demonstration in the courtyard of the Sorbonne was met with violent police action.

Prelude

This is the tale of the revolution which occurred in Paris in the month of May, 1968.

Revolutions are the ecstasy of history: the moment when social reality and social dream fuse (the act of love).

The reasons given for their happening are always insufficient, their descriptions, always partial.

The May revolution fought for the visible (bread) and the invisible (a new order).

The tale must be told in metaphors.

Need, and consciousness, brought action.

Action against the new order illuminated the carcass of present society. Crystallized the dreams of the "actor-participants."

Almost all which is visible has now receded, apparently. The invisible is in people's minds. The minds of the participants.

It has reversed a balance so old as to appear immutable, before this revolution.

The collective hopes of a new order are now incommensurably stronger than the small, private fears nursed by the injustice of the present.

One: one pleasure has the bourgeoisie, that of degrading all pleasures

Flashback-Nanterre. A contemporary fable.

1963. Wednesday. Weekly cabinet meeting. A university campus is needed. (progress)

Preferably on the outskirts of Paris. (planning)

The then Minister of the Army Messmer to the then Minister of Education Fouchet (of the Interior in May '68): "I have a small piece of land, west of Paris, at Nanterre. You could use that if you want." (politics)

It was an air-force depot, in the middle of wasteland and shanty towns.

Surgit Nanterre.

1968. Concrete and glass; for the middle class of the 16th and 17th arrondissements, the rich residential areas of Paris, her mausoleums. And parking lots; lots of parking lots for the sons of the well to do, who live with the family and use mummy's car. (the family)

Around the campus, still the Arab and Portuguese shantytown.

Underdeveloped teenagers playing football (their ribs! their language!) on the periphery of life. Chimneys, council houses, wasteland. On the walls, written by a spray pistol:

URBANITY, CLEANLINESS, SEXUALITY.

Twelve thousand students. Fifteen hundred live in residence.

Dancing once a week, cineclub twice a week, and telly the other nights. Telly, the opium of the masses, but also the self-inflicted masochism of the intellectuals. (culture)

On a wall: SQUASH YOUR FACE ON THE WINDOW-PANE LIKE AN INSECT AND ROT.

The rooms are good and sterilized: big glass windows overlooking the Arab barracks. No visits by "foreigners" allowed, you can't add or change furniture, you cannot cook. No politics on the premises.

On the external walls: HERE FREEDOM STOPS.

Girls (over 21, or with a special parental permission) can visit boys in their rooms. But boys cannot visit girls, because — says the minister — nature has its laws, which are better acknowledged than forgotten. Also — says the minister — "the girl residents are not really willing to have the boys intrude into their feminine world." (ethics)

A handful of Maoists, trotskyists, anarchists, situationists; yes, and Cohn-Bendit. (the extremists)

That is, before the deluge.

Sociology students are the most active. But militants operate in a vacuum. Their only rallying issue: Vietnam. (mythology of the left, alienation of the majority, consciousness of a few)

Few names on a black list: the names of the militants. The dean, Grappin, good father, liberal man (he was in the Resistance) denies strenuously the existence of the black list.

But strange raincoated men appear on the campus. They must be the men who check on all "Vietnam Committees," which are very active in Paris.

The raincoated men take photographs of the "extremist" students.

The students take photographs of the raincoated men and pin them on the boards.

In the interminable corridors, boards say: "FLN will win." And: "All reactionaries are paper tigers." Vietnam is in Vietnam. The students ask the sociology professor for Chris Marker's film on the big Rhodiaceta strike to be shown. The professor says no.

The students want to discuss William Reich's books on repression and sexuality. No.

They begin to talk back to the professors.

Who is Charlemagne, professor emeritus?

Charlemagne was a very good king who fought for Christianity.

What do the workers eat for lunch, professor emeritus?

They eat what they get, my children, but let us concern ourselves with the things of the mind, and not be distracted by trivia, because a brilliant future is in store for you, if you apply yourselves with discipline, and learn with discernment.

Anonymous hands write on walls: "professors, you are old."

Something is not working, there are cracks in the walls.

Minds are troubled. A few troublemakers excite the students.

Ministers are faintly annoyed.

Minister Missoffe comes to inaugurate the new swimming pool.

He has written a book on youth, as ministers of youth should.

Spotlight. Amphitheatre. Minister speaks, students listen.

Student Cohn-Bendit interrupts: "I have read your books" — he says — "Six hundred pages of rubbish, you don't even mention sexual problems."

Minister in a rage. Loses his cool: "no wonder" — he says — "with your face, you have such problems ... go take a swim in the pool..."

Papers start talking.

The medium being the message, mass media point the road of self-recognition to the students.

The barbed wire of deferential respect is old and rusty. Questions are pincers. The university, factory of knowledge, has its first wildcat strikes.

Professors are kings stripped by questions. Laughter, the gay and suddenly easy art of desecration; professors soon are naked kings.

Under the small-arms fire of the light brigade of vociferous dissenters, joined by the cohorts of the alert and interested, professors run for cover.

News reverberates. Italian students have already learned to cut bus tyres, to throw sand into the eyes of the flics pursuing them.

German students are coping with dogs. Civilizations differ from each other. Different answers for different situations.

On the 22nd of March, the students occupy the administrative building singing "La Carmagnole," especially revised for the circumstance and dedicated to their dean Grappin (dansons la grappignole ...).

Students with frail hands and troubled minds. Students, sons of the bourgeois, enclosed within two ghettos: the university-factory where they give answers but don't ask questions; and the ghetto of privilege.

Their minds are policed by discipline, patrolled by examinations. Their hearts frozen by authority. Their state within the state mimes the society from which they are insulated. And yet, they do not own and they do not belong.

Their past, mystified by the all embracing suffocation of family ties, the humiliating dependence on family money, pushes them towards a present which asserts dogmas and denies learnings; asks for collaboration with the big enterprise of camouflage, collaboration with the perpetuation of production without questions, consumption with no answers.

Their university mimes society, mimes the factory. They threaten its functioning, using gaily and daringly the shreds of learning handed down to them. They reconstruct patiently in the silence of their rooms the pieces of the puzzle which needs them obedient and well behaved, respectful to their grave and grievous masters and mindless to the outside world. And yet the tools they are handed, however blunted by their majestic keepers, spell irreverence and reveal traps, false doors, distorting mirrors, barriers, closed gates. At the very end of the long dusty roads: injustice.

11th April. Rudy Dutschke is shot.

Very fragile ties with those to whom you are similar, who are defying the same small semigods, on the other side of ridiculous frontiers.

In the Latin Quarter students congregate and talk.

Scattered at first, then in groups, finally: a demonstration.

Troubled waters, ripples, waves.

Rotary presses start rolling.

Pierre Juquin, communist M.P., member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, comes to Nanterre. To talk about the "communist solution" to the "student crisis."

And leaves by the back door.

The "March 22" constellation attracts the stardust, its brightness illuminates ironically a still very dark sky.

But the university-factory is now in danger. Grains of sand have brought the machine to a grinding halt.

Nanterre, the factory is closed.

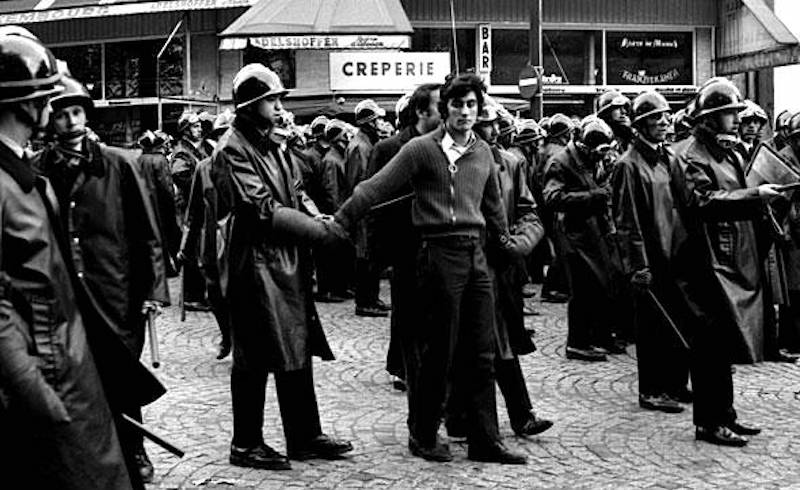

The police come, force the students out, line them up, hands behind their necks (Vietcong photos?) and search them for weapons.

Vietnam has never been so far, or so near.

The flics do not find weapons.

Tomorrow, the Nanterre students will be at the Sorbonne.

Two

Thanks to teachers and exams

competitiveness starts at six

(HANDWRITTEN POSTER)

Let's open the gates of nurseries,

universities, and other prisons

(NANTERRE, CONCERT HALL)

Sorbonne the Alma Mater.

Sorbonne mater dolorosa where the dark ancient rites of initiation and consecration are performed. Sorbonne mater dulcissima, where the golden fruits of scholarly minds blossom in secluded cloisters, well protected from the winds of history and the infinite infections of vulgarity. Sorbonne the citadel. Sorbonne the fortress. Dean Roche is a mouse. A pathetic, little, miserable old grey mouse, fond of dusty corners, feeding on the significance of thirteenth century debates about angels on tops of needles.

Dean Roche is also a shit.

In the courtyard of the Sorbonne a few hundred students are discussing politics. Distant politics: Vietnam, and their own politics: the closing of Nanterre.

The police precipitated things there, acting like a catalyst. The students, and some of their teachers-keepers, had to face the emissaries of the naked king, the faceless long-arms of the system which rules by mystification, but when that eventually fails, by brute force.

And as in chemistry, and politics, forces attract or repel, according to your inclination, conscience, interest, understanding, atomic structure, or place in society. Students are economically blackmailed by their families, mentally repressed by the teaching system, but within reach of the tools of understanding.

They are now at the Sorbonne, defiant and very determined, knowing that a squalid commando of thugs nursed by the police might come. (the Occident)

Roche, the mouse, is genuinely frightened.

All of his courtyard full of students (he will say on radio).

The minister is uneasy too. The time when an organized band of fascists can cope with student troublemakers is long past.

Roche calls the prefect of police. Grimau, and is assured that the flics are ready, in case of an emergency.

Students pack the Latin Quarter.

Roche thinks the situation is beyond control (that courtyard!) and asks Grimau to send his flics.

Now, Grimau is a sensible person. Like all people in command he has been a student too (and he also knows what his mercenaries are capable of). He tells Roche he wants the request to be put in writing.

The dean Roche, the mouse Roche and the shit Roche, in one person assembled, signs.

Latin Quarter meeting place, Latin Quarter vicarious myth. Narrow streets of cobblestones.

Boulevard Saint Michel starts at Place Saint Michel, by the river, and goes up, very straight, to the gardens of Luxembourg.

Boulevard Saint Germain crosses it. Place de la Sorbonne is half-way up, on the left.

Place de la Sorbonne is in front of the Sorbonne, which has one entrance there, and another in rue des Écoles. The Sorbonne has a central courtyard. In the courtyard, if one looks up, one sees a square of sky.

Many are the "species" of flics needed for law and order. Metropolitan police: 70 thousand, of which 22 thousand are in Paris. They wear long black raincoats and have batons made of wood, and painted white.

Special intervention groups, the élite of the flics, wear khaki uniforms. They are very well trained: specialized in anti-riot techniques.

C.R.S.(S.S.) are a reserve police force, at the disposal of the Minister of Interior. They are fifteen thousand and have black, india-rubber batons.

"Les gendarmes mobiles" are also in black, they are fifteen thousand strong and take orders from the army. They have rifles.

For practical and poetic purposes, students, demonstrators, and generally the population will soon call them all C.R.S.(S.S.), in a rhythmical, obsessive chant which can be derisory, defiant, mocking, hateful. When referred to in the third person, they will be all called: flics. Or, of course, epithets.

Called by Roche, the flics surround the Sorbonne, and force their way in from rue des Écoles. The four or five hundred students in the courtyard assemble to one side, near the chapel. Student leaders negotiate with the intruders, and are told that they may leave unmolested, if they leave. By now the flics have forced their way in from the other entrance too, and surround the students. The leaders agree to leave, some students are helmeted, some have dismembered two tables and brandish the legs as clubs.

A corridor is formed, a corridor of flics through which the students must go out. At the door, they are picked up and thrown into black marias.

Many are roughed up.

Students in adjacent streets see, and pass the word, and shout.

Gatherings. Groups.

Boulevard Saint Michel is students.

Boulevard Saint Germain is students.

Place Saint Michel is packed.

It's five o'clock.

The light artillery of the mass media sends its scouts.

Quivering antennae will rove the arena, indefatigable gnomes of ether will send messages which will trouble all good people in their very private homes.

The state of the battles will be offered in detail, packaged yet murderous, dynamite wrapped in cellophane. In homes where the non-participants hear of the behaviour of their emissaries, blades will penetrate thick layers of consciences.

The young of the frail hands and troubled minds, those evicted from the sleep-castle are only half awake and stirring. From now on they will be in the streets to shout naked words and wishes.

The waves will bring news of their comrades, invisible now through the gases and the rage, to their transistors, useful news, on how the fighting develops from minute to minute.

Gatherings. Groups. The electrons of the atom dance a ballet of self-discovery

Barrages of black flics. Leather and steel and plastic.

Forgotten nightmares. Masks of blindness. Lines of fear.

Sweet and sickening taste in the mouth. Dry palate. Bowels.

Memories of ancient armies, of unbeatable cruel leaders of hordes, unleashing successive waves of screaming furies. Martians. Monsters of planets of steel and ice. Men in uniforms performing dark rites.

Shouts and chanting. Electricity. Lightning. The magic power of the rhythmical word which casts spells. Gatherings around the chants, silver chains of sound, thin protection of air and space.

The first wave.

Scattering butterflies.

The black army is now a wave of black men inflicting pain with white clubs. To be left alone is to be grabbed and clubbed; it is falling down and being kicked by many converging on the prey. A girl lies unconscious. Grenades make bangs and blue clouds.

Radios screech.

Cars circulate: fish in an aquarium.

Cobblestones. Stones found near the trees.

Traffic-signal poles are pulled out. Long spears to attack the black marias and to be used as levers to loosen more cobblestones.

Pavés. The streets offer their skin of stones. Pavés make arcs which last seconds.

The first flic of leather and steel falls, crushingly, his spring broken.

The bangs of the grenades punctuate the battles.

Nauseating gases impregnate streets and lungs. Protection, regrouping, embryos of barricades, then — barricades.

Long files of black marias inexorably working their way up from Place Saint Michel.

In their receptacles, good people eating their dinners consume the instant poison from their radios.

Captured students are taken to Notre-Dame-des-Champs police station.

At ten it starts to rain.

At eleven, the flics are masters.

The Sorbonne — ringed in black.

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]