The Man Who Closed The Asylums

In 1961 an Italian mental asylum on the iron curtain got a new director. Within seven years he changed the face of contemporary psychiatry.

A photo from Gorizia in 1965 captures the situation inside the psychiatric hospital in the city before journalists and photographers arrived to spread the word. The caption reads ‘Self-portrait: 1965. Ward B.’ There are forty or so men in shot, some standing, some sitting. They look a bit like a football team or a school class inexplicably comprised entirely of grown-ups. Franco Basaglia can be seen in the middle of the image, in a shirt, jacket and tie. His colleague Antonio Slavich is nearby. A few nurses also seem to be present, in white coats. The rest are patients. The group is on the steps of one of the hospital’s buildings, in the sun. Few people had heard of Gorizia or Franco Basaglia in 1965, but by 1968 this would become a celebrated and exalted place, a hotbed of change, an extraordinary example of ‘an overturned institution’, somewhere that was soon ‘idealized and mythologized’.

It looked like a dead-end job. A vacancy at a grim mental asylum, right on the edge of Italy, miles from anywhere: a new director was needed there. The first time that Franco Basaglia visited the place, it made him feel physically sick. He remembered the smell of ‘death, of shit’. Memories of the six months he had spent in a fascist prison in Venice in 1944, as a twenty-year-old, came flooding back. It was 1961, winter, and Gorizia seemed like the end of the earth. In many ways, it was, at least in European terms. This provincial psychiatric hospital (built under Austrian rule, in 1911, and originally named after Franz Joseph I) had the iron curtain – the border separating Italy from Yugoslavia and therefore from a different world, the Communist Bloc itself – running through its very grounds (where it was marked, at times, simply by white signs on the ground). Yugoslav guard posts overlooked the hospital. It was a peripheral place, in a forgotten, ossified city. It was the ‘most peripheral, the smallest and the most insignificant of all the Italian asylums’. Edoardo Balduzzi referred to that post as ‘an authentic form of exile’.

Inside, behind the classic asylum architecture of high walls, gates, fences, bars and heavy closed doors, Basaglia found over 600 patients. Two thirds of them were of Slovenian origin, and about half did not speak Italian as a first language. Around 150 of these were in the hospital as part of post-war peace agreements. Basaglia referred to this group as ‘patients who could not be removed and for whom an internal solution was necessary . . . they had no prospects beyond the hospital walls’. The Cold War, which had so deeply affected Gorizia, was reproduced in a stark way within the asylum walls. But the history of the asylum had always been caught up in the city’s own tragic history. Inaugurated in 1916, the hospital had been completely destroyed during World War One, like most of Gorizia itself, and was subsequently rebuilt under Italian rule.

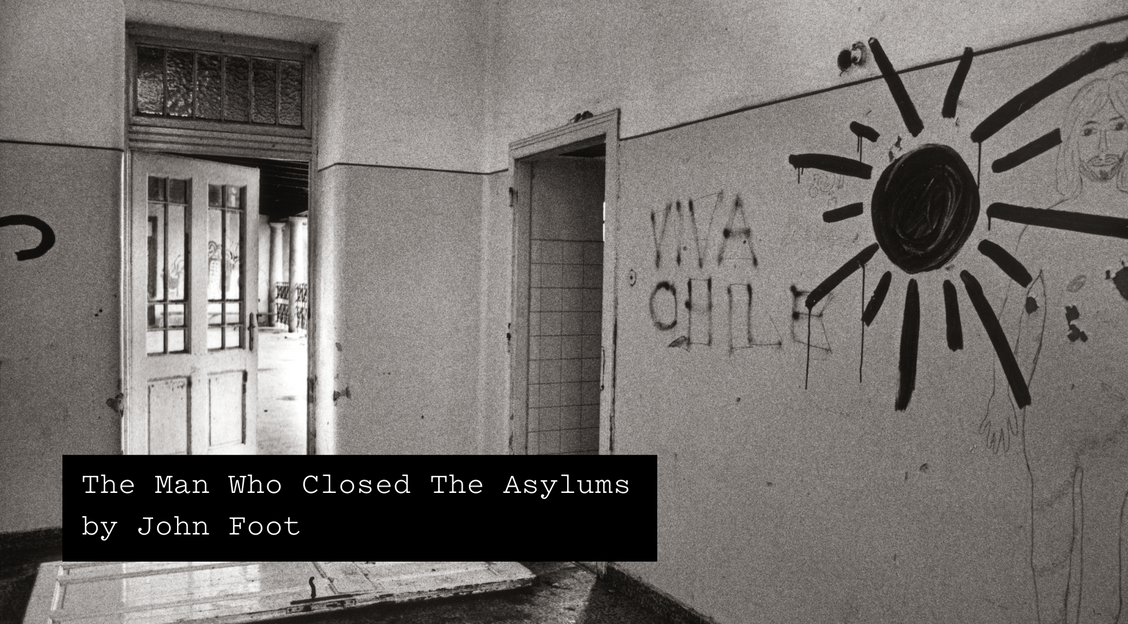

Gorizia’s manicomio (madhouse) was a dark and sinister institution, a dumping ground for the poor and the ‘deviant’, a place of exclusion. As in most Italian asylums at that time, an architecture of containment and control had developed over time, with cages for the most unruly patients and beds with holes in them through which the immobilized could defecate. Some patients were tied to their beds most of the time, and the hospital’s beautifulgardens were hardly used. Even when inmates were allowed outside, they would often be bound to trees or benches. All the wards were closed under lock and key, and the vast majority of those inside were contained against their will. They were inside because they were, in the opinion of the judiciary and the medical staff, a ‘danger to themselves and to others’. Many had been left to rot for years, inside the asylum, with no prospect of release. ‘Therapy’ was largely confined to electroshock and insulin shock treatment, and occasional work in the asylum’s kitchen gardens. The introduction of anti-psychotic drugs in the late 1950s was just beginning to have an impact by 1961.

It was the last place where you might think about starting a revolution. But Basaglia took the job, and within eight years Gorizia was to become the most famous mental asylum in Italy, if not in Europe. It was here that a spark was lit, leading to a movement that would undermine the very basis of all such ‘total institutions’. Nobody expected this outcome in 1961, certainly not the provincial authorities that had employed him, nor Basaglia himself. Most asylum directors at the time simply managed the situation they inherited. Many were failed academics. Very few tried to implement any kind of change at all. In this, as in so many other things, Franco Basaglia was very different to the rest. The ‘revolution’ in Gorizia took place almost by chance. If Basaglia had gone somewhere else, the asylum there would probably have remained as it was.

— Excerpted from The Man Who Closed the Asylums: Franco Basaglia and the Revolution in Mental Health Care by John Foot

[book-strip]