The Second British Revolution

In the years leading up to World War I, Britain was rocked by an unprecedented upsurge of labor militancy. As James Robins writes, as millions went on strike across the country, was this Britain's lost revolution?

I.

Beneath six hundred tonnes of wrought iron and plate glass, on the first night of November 1913, Britain’s grievances gathered to rage and roar. From wharf and mine, slum and shop they came: ten thousand souls rushing the doors of the Albert Hall to secure a seat or a precious patch of floor; twenty thousand more left to mill and grumble and smoke at the fringes of the gaslit garden. Their hot and impatient demand, inside and out, was a simple one, loud enough to be heard in Westminster and across the gales of the Irish Sea. Dublin was at war with itself, a city besieged from within, and James Larkin – the charismatic chief of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union – had been jailed four days earlier on a charge of sedition. From the chamber rose the call: an immediate end to the lockout of Dublin’s labourers from the docks and tramways, and the unconditional freedom of Larkin.

Though honest and righteous, the simplicity of the demand was deceptive. The rally was not just another appointment in the regular schedule of working-class politics in the second decade of the twentieth century. The stream of history which bore thirty thousand people to the Albert Hall and stamped an outraged cry on their tongues was hurrying into wilder territory. Up there on the platform, each speaker seemed more eccentric and varied than the last, the kinds of people who a few years earlier would never have had cause to appear together. Here was Charlotte Despard: an ancient and adamantine feminist sheathed in the forbidding black of a widow. Here was a serene and bearded bohemian calling himself “AE”: an Irish poet-mystic of winged horses and druid mounds. Flanked by Delia Larkin and Dora Montefiore – recently thwarted in their plan to smuggle children out of Dublin by a flapping bandit-gang of Catholic priests – was Larkin’s deputy in the ITGWU, James Connolly, pithily summed up by the Daily Herald’s reporter as “sheer massive argument.” George Lansbury, the East End champion, declared that he saw “no difference between the upheaval of the workers and the upheaval of their wives and sisters.”

The longest and loudest cheers were held in reserve for a woman smuggled in by the back door, a woman midway through a months-long battle with the police and the Home Office that would see her jailed, on hunger strike, released, then imprisoned again eight different times. For standing to meet the thunder on the platform that November night, Syliva Pankhurst was expelled from the family firm: the Women’s Social and Political Union. The applause, for now at least, was consolation enough.

Never shy of a brawl, the playwright George Bernard Shaw got up to rail against the police: those “mad dogs” sent to bludgeon the heads of workers in Dublin, Liverpool, and Bermondsey. A straight fight, Shaw warned, “can only end in one way – that all respectable men will have to arm themselves.” The chamber howled approval, and from its mass came a single strong voice to ask the most teasing question of all: “What with?” Freeze this moment, embalm it in amber, and we find three separate movements discovering for the first time that they were really one movement speaking in three accents. Irish republicanism, the militant women’s movement for suffrage and rights, and the workers’ struggle: these were the grievances which had delivered Britain from Thames to Tyne into the rough hands of a near-constant state of crisis for the past three years.

By teasing armed combat, Shaw was only keeping with the general attitude of these years – years in which workers took to carrying revolvers and fought gunfights with blacklegs, years in which rough action was common, regular, and expected. “People talk of the ‘Dark Ages’ as something remote in time and of ‘savagery’ as something remote in place,” the Daily Herald warned in its editorial on the Albert Hall meeting. The agents of a New Dark Age, “are all around us, and it will take much more than enthusiasm to dislodge and destroy them.” With their phosphorous and firelighters and toffee hammers, the suffragettes had introduced the country to the virtues of political terrorism and made themselves the enemy of all that was vicious and moralising in Britain. Edward Carson and his legion of Orange goblins were very far down the road to insurrection with their blood-oaths and well-drilled brigades in Ulster – backed to the hilt by a Conservative Party fully prepared to stage an uprising against the state in the name of loyalty. A clique of Blimpish army officers were mouthing the sounds of mutiny in defence of Carson; the troops at their command already had experience guarding critical infrastructure in the cities, and were well blooded-in by constant battles with strikers. This was, in short, one of the most uncertain, anxious, and fearful periods in the entire bloody muck of British history, certainly the most violent since the Civil War.

At the core of the crisis, its livid and racing heart, was an unprecedented rebellion by the workers, detailed in Ralph Darlington’s rigorous recent study Labour Revolt in Britain 1910-1914. After twenty years of setbacks and quietude, from the collieries and ports and railways an attitude of stark defiance spread into trades and industries which had barely known organised activity, let alone the kind of militancy and radicalism which defined the tumult. Every strike from the end of 1910 until late summer 1914 – thousands of them – turned out not to be the culmination of a struggle or the settling of a dispute but a departure into unexplored lands. It was driven by the twin forces of rank-and-file agitation and the unofficial solidarity strike, and no moment before or since has matched its speed and its strength. Within three years union membership grew by 62 percent; though larger in absolute size, the General Strike of 1926 by comparison looks like a sad shadow of an earlier possibility.

The Albert Hall meeting was the first time Britain’s radical causes had met on a common platform. As surely as warp binds with weft, each had found a security and fastness in the other and, under Shaw’s sharp suggestion, they trembled on the edge of new objectives. It was also the last. Cleaved apart by the First World War, the labour revolt, Irish republicanism, and militant feminism would never again find themselves obliged by circumstance to join hands. Too much would change in too short a time. Yet history is only a fugitive from paths not taken. Defer the coming European conflagration, push it forward in time perhaps a year, and what fills in the void? Allow the imagination to unspool and it becomes possible to think of this November night as the first dusk of a different future.

Yet even if we allow the line of fantasy to loosen and play out a little, this is still an occluded age to our eyes, massively overshadowed by the War. The popular image handed back to us is a delectable one: a panorama of meadow picnics under parasol, of dollhouses and upstanding Christian morals, of starched collars and careful curtseys and orchids grown under glass, and somewhere softly in a distant room the scratchy hum of a gramophone record. Such scenes, recalled to the modern mind, are not illuminated by the wan light of truth but the bright shellbursts of the Somme: a folk remembrance of dreamier days before the fall, the hazy illusions in which the upper classes found their refuge from fret and strife and worry. Because this was the era of the skyscraper, the grand prix car, the aeroplane and the submarine, split atoms and spilled radium, the strange warp fissures of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, women and men alike turned raving by the irresistible pace of their time. The christening of each new behemoth, the opening of the latest vast wonder, the overturning of every old order signalled a fundamental instability at the heart of things. Henry Adams, that eminent historian of America, hurried breathlessly through the shifts: “Prosperity never before imagined, power never yet wielded by man, speed never reached by anything but a meteor…” Such qualities “made the world irritable, nervous, querulous, unreasonable, and afraid.” Fuelled by iron dust and cordite and petrol, civilisation had gathered itself into great vortices of steel and copper and steam, dragging whirls of telephone wire behind it. The only undisturbed uplands of bliss were those dreamed to ward off an ambient feeling that a conflagration might be coming, that apocalypse was in a hurry. All was shatter and velocity; a false arcadia bloodied and reeling.

[book-strip index="1"]

Bulging with bullion hacked from South African mountains, supping down tankards of Rockefeller oil, Britain’s gorging layer of magnates and chairmen seemed to be taking on the appearance of a plutocracy. Staking their opulent visions on an undying empire and stashing their wealth in its innumerable harbours, the first decade of the twentieth century was a stunned witness to their supreme self-confidence. The bosses consolidated their holdings and strengthened their lobby groups into colossal weapons of industrial order capable of bringing about the Taff Vale judgement (which held unions liable for losses of earnings during a strike) and the Osborne ruling (forbidding unions from donating to political parties). After the recession of 1907, as cities churned muddy with the march-lines of the hungry, employers demanded ever-stricter military rigour from their workers and chipped away with glee at their meagre pay.

Twenty years distant from their last great victories, the trade unions had ossified into submissive bargaining units. Their leaders – moderate, cowed, pleading – made a fetish of negotiation, fearful of losing what little they had once gained, often refusing to call strikes no matter how serious the dispute. As the Edwardian era became the Georgian, a glimpse at the ballots revealed nothing of the enclosing storm, no whiff of the resentment and unease roiling beneath the usual operations of the realm. Every election the vote split roughly evenly between Liberals and Conservatives, with the dregs collected by a nascent Labour Party hemmed in on one side by its own modest, meliorating, middle-class Fabian virtues, trapped on the other by an electoral pact with the Liberals.

And the workers? Seen from afar – from the frosty window of a passing carriage, say, or the deck of a great liner coming into port – the workers of Britain seemed to be clothed still in the straitjacket of Victorian respectability. Religious, dutiful, reverent of their betters, with an unrewarded faith in the virtue of honest labour, they appeared to regard the method of collective bargaining not as their salvation but a modest plea for modest changes. Yet those same workers were better attuned than most to the neuroses and fears of the industrial world, closer to the roots of that force which moved the age to a more terrifying pace; only the workers could heed the low thrum of power history was playing for them. Against all these facts they rebelled – against the cowardice of their leaders, the brutality of their bosses, against the very fact of respectability – and kept rebelling until by the early summer of 1914 the lace doilies and stiff taffeta of Britain’s ballrooms began to shiver at the whisper of a single word: revolution.

II.

In his small stall, staked and braced with barely enough lumber to hold the heaving mantle above, the typical British coal miner was aware – however dimly – of an enormous, terrible fact: he made the empire move. The black mass hewn by his hand, which gummed up his lungs and the lungs of his father before him, fed the steamers lugging tea from Bombay to Belgravia, the same freighters which were defended by the high-speed coal-fed turbines of HMS Dreadnought, shovelled again by firemen haring the railway arteries, and which churned the engine hauling him rattling in his hoist cage breathlessly back from a hostile realm. By definition he worked in an abnormal place, but an ‘abnormal place’ in the miner’s ancient and strange language was a specific part of the seam where a decent day’s wage was tougher to get, where clod and stone spoiled his take and carts were hard to find, where the air might be too swampish or parched. Rough byzantine negotiation between miners and their managers set the piece-rates for abnormal places, and in August of 1910 seventy miners at the Ely colliery in the Rhondda Valley rejected a cut to them. Their refusal to starve, their defence of the common rule which somehow had not yet found its way into the mines of Britain, set the tone and timbre for the next four years. South Wales breach-birthed the rebellion, let free its heaves and ferocity and thrill.

Like many of their type, the mine’s owners were confident and belligerent. Challenged by those seventy miners at Ely, the bosses of the Cambrian Combine did what seemed sensible and massively overreacted, locking out all 950 miners at the pit. Within a week, sympathy strikes were stalling other Combine collieries, entirely unsanctioned by the South Wales Miners’ Federation. The union’s president William Abraham, a bear-man who went by the name ‘Mabon’, a Liberal-Labour MP for Rhondda since 1885, rent his clothes trying to stop his own members. He begged the miners to respect the agreed channels of negotiation. But they were in no mood, and only a ballot could go over Mabon’s enormous head. By November, 12,000 Combine miners were on strike, joined by 11,000 more in the nearby Aberdare Valley pits. Another month and 30,000 men were out across South Wales.

At street corners and pit gates and loading platforms the miners set their pickets. Scabs were treated with the respect deserved by their kind: abused, harangued, hounded out of town, the initials ‘BL’ (blackleg) smeared across their doors. Trains bringing in scab labour or taking out coal were stopped, their windows broken with rocks. The employers mobilised in turn. Through November, strikers fought running street battles with local police and their reserves ordered in from Bristol and Cardiff. On the 7th, thousands of picketers were forced back from the Llwynypia pit by repeated police assaults, killing one Samuel Rays, and for their revenge the miners set to work on Tonypandy’s town centre. The Times called it an “orgy of naked anarchy,” yet the riot was finessing and deliberate: only the shop-owners who backed the Combine bosses had their displays busted in. When the miners looted, they looted only what they wanted. Some were spotted trying on clothes in front of mirrors before showing off to their friends in the square.

By October the pits were ringed thick with infantry and hussars sent by the War Office. The workers sought their own troops. Bill Haywood, beloved founder of the American IWW, brought his two-hundred-pound heft and scowling Easter Island face to Aberdare, appearing alongside the raked scarlet hat of Madame Sorgue of the French CGT, nicknamed by the press la belle anarchiste. In Haywood and Sorgue, in the hopeful faces of those who turned out to hear these titans speak, was the faint gleam of a new force in trade union life: an idea not modest and native-born but foreign, militant, joyfully disrespectful of old men and old attitudes, ruthlessly class-conscious. The arrival of syndicalism in the Welsh valleys is difficult to trace, though Darlington credits Noah Ablett, a Rhondda-born miner who chucked in his dreams of becoming a parson when he won a scholarship to Ruskin College. There, with a clique of radical students, Ablett founded the educational group the Plebs League. Armed with a zealous Marxism he returned to Rhondda and converted several local branches of the Independent Labour Party to the League’s thinking. It was Ablett who sewed in those subterranean warrens the germ of an idea which, even in the face of the British worker’s traditional suspicion of coherent ideological projects, grew to define and drive the revolt.

By grit and guile the Welsh miners managed to hold out – until August of 1911. Ten months of bitterness, and it ended pathetically. The strike was killed not by the fixed bayonets of the Somerset Light Infantry but by the miners’ own union. For rejecting all pleas for compromise and agreement the SWMF and the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain withdrew financial support, forcing the workers back to the pits on terms no better than what had been haggled ten months earlier. By spite and stupidity, with their worst habits already encrusted, the union leadership (many of them, like Mabon, also Liberal MPs) betrayed the people they were supposed to defend. In this sense South Wales prophesied the coming years and taught the workers early that no faith was safe from the brutish interventions of reality; that what had once been sure and secure could no longer be trusted.

South Wales lacked only one element, an element that would soon become a dominant feature of the revolt. It was being demonstrated, at the exact same moment, by the soot-smeared women of the Black Country. In the backyards and outhouses of their own slum homes, while their husbands seared themselves in foundries, the women of Cradley Heath made chains for as little as seven shillings a week (the average male wage being around 25s). Their ‘forges’ were not much more than domestic fireplaces. As soon as they were old enough to grip the iron forceps from the fire, their children were put to work.

Mary Macarthur was no saint and she had no salvation to give, but this steely Scotswoman gave the chainmakers a new spirit. Starting in August of 1910 Macarthur led a ten-week strike for better pay. Lacking its own strike fund, the National Federation of Women Workers instead went to the nation: a leaflet-and-letter campaign which pulled in more than £4000 (around £482,000 today, in Darlington’s estimate). Macarthur used the cinema – that enchanting new phenomenon – to reach an audience of ten million people. NFWW membership quadrupled in Cradley Heath, and the strikers’ children were nursed through on donated milk as if nothing had changed. Such was the wealth – meagre when weighed against their enemies, and unappreciated, but worth all the treasure in the world – which the workers could lend each other. By the simple, tender gesture of passing a chunk of bread to a child, a different reality was conjured, a reality in which poverty was not a god-given condition but an imposition from above, an imposition that could be broken. As Mary Macarthur and the women of Cradley Heath proved, no true workers’ rebellion could ever be fired by men alone.

III.

Mid-June, 1911, and middle-England was preening and puffing at the imminent coronation of George V. Days away from the ceremony, the country’s ship-workers emerged from their holds and engine rooms, descended the gangways, and refused to go back. The strike, led by the National Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union was supposed to be modest – and it was not likely to win. Their employers (including Cunard and White Star, owners of the Lusitania and the under-construction Titanic, respectively) were affiliated with the agile and vicious Shipping Federation which operated an able strikebreaking wing with its own minor fleet to ferry scabs around Britain’s ports. As wages sunk to humiliating levels, with the very fact of union recognition at risk, the NSFU turned to face a baleful choice at the onset of summer: strike or die.

On their way out, the sailors appealed to their opposites on the docks: the haulers and porters, the warehousemen and crane-operators – the precarious grunt-labour which by sweat and danger made real Britain’s reputation as the epicentre of global trade. Though seventeen different waterside unions had affiliated to the new National Transport Workers’ Federation in March, joint action between sailors and dockers had not been considered. It happened anyway. The dockers made it happen. Their leaders preached at them to do what was "reasonable”; being unreasonable was precisely what the stokers and stevedores had in mind. Together vaulted the invisible barrier – a relic of the days of craft unionism – isolating workers of different trades and grades, and at the meeting-place between realised their condition was commonplace: more united than divided them. Learning as they went, the unorganised dockers discovered the vital principle of solidarity.

The strikes went in circles. The sailors called out the dockers, and when the sailors won their agreement they immediately struck again until something was settled with the dockers. At the shores of the nation, at almost every major commercial port, momentum churned like a whirpool. Under the banner “Our Poverty is Your Danger,” 12,000 waterside workers in Manchester and Salford let loose a spree of riots. At Shudehill Market pickets fought brawls with cops while women pelted the police with peas and raspberries. In Cardiff, the lumber-haulers and brewers turned out alongside wagon-makers and foundry toilers, bringing the total number of strikers to somewhere near 15,000. Women from the workshops joined in, pitching barrels of beer into the harbour. The Labour Leader (then run by Fenner Brockway) reported what was evident everywhere: “These poor, disorganised workers seemed to grasp the principle of unity as thought they had been gifted with a new vision, and from all such disorganised work-places we saw the men and girls in the Sunday best marching in fours to a lodge-room.”

[book-strip index="2"]

Lithe, powerful, hard-edged, a panther on the platform, growling from under an immense moustache: the veteran radical Tom Mann was an apparition devilling the country in those weeks. An ex-miner and an ex-docker himself, Mann chased the ripples of the strike wave, fists forward to the sky, baring his shirtsleeves in an age when taking your jacket off in public was still considered vulgar. When, with great speed and violence a fresh pulse of rebellion burst in a city, Mann was somehow already present, arranging a strike committee, printing manifestos, selling copies of The Industrial Syndicalist – the weekly paper of the Industrial Syndicalist Education League which, along with the Plebs League, formed the hard core of radical intellectual temper. Mann was not eloquent, but he was direct, and possessed the stormy force of an enormous personality; an ardent believer in syndicalism smart enough to acknowledge that British workers were suspect of doctrines. He was of a mind to practice his theory, and prove it could work.

Mann’s dark twin in these years was George Askwith: mild of manner, placid, ameliorating, almost ascetic in his commitment to arbitration as head of the Labour Department at the Board of Trade. With energy equal to Mann’s, Askwith zig-zagged the country begging parties to negotiate. From Hull, where the dockers were almost entirely unorganised, Askwith noticed the change in mood, a change which he, in his infinite patience, could not help. “The union leaders,” he observed, “have little control and are now frightened.” Totally hostile to any attempt at mediation, the Hull dockers still had leaders, just not of the established unions. One of these outsiders, the syndicalist John Burn, introduced the innovation of a permit system. The workers controlled the ports and the goods trapped inside, and only they could decide who accessed them. Anyone, technically, could apply for a permit but the workers always refused except to release supplies for workhouses, clinics, schools, and hospitals. The permit system spread to Cardiff, and then, when it finally joined the fight in the early days of August, to London.

That fetid summer. In the terraced slums of the East End temperatures threatened 40°C. Butter spoiled in the bowels; meat turned gangrenous in the holds. The Underground, lacking coal for its power stations, nearly stalled altogether. Motorcars – no better symbol of this age of velocity – seized without petrol. Some 77,000 dockers were out, joined by granary workers and dustmen, tugboatmen and grimy fuel porters; anyone at all connected to dock-work was urged to down tools. Women employed in the food trades in Bermondsey marched in the street chased by the mingled smell of pickles, jam, chocolate, and glue: evidence that the undimmable Mary Macarthur had been hard at work. Two hundred thousand Londoners, it was estimated, were sent home because nothing moved. Newspapers reported their own imminent disappearance: good newsprint was drying up. Even the sympathetic Daily Mirror spoke of a “state of siege” and a capital “almost face to face with famine.”

Yet every night – those blazing, scented nights of August – the strikers went to Tower Hill and convened what looked to the trained eye like the opening sessions of a workers’ assembly. The zone of control of this impromptu peoples’ parliament was the entire Thames Valley. They took their rallies to Trafalgar Square and under the vaulted gaze of that one-armed reactionary, threw their hats to the humid wind. The fact of being out was a victory in itself; they had to strike over the heads of the NTWF which urged them to accept a settlement with the port authorities. Ben Tillet, who with Tom Mann had led the 1888 London dock strike, preached in vain the virtues of stable bargaining rules yet even he was obliged, on the platform at Tower Hill, to bend to the temper of the times. When he did, Tillet recognised something new and unnerving animating the crowds – just as Askwith had in Hull. A fresh zeal, a “spirit of revolt” which had “as if by some great magic wave of electric telepathy” transformed the women and men of London. “A new demeanour” overtook them, an awareness of their own half-grasped, barely-dawning capacity; a recognition that this struggle had already surpassed the normal, usual circular plea for more wages and eased conditions. The attitude was frenzied, aggressive, militant to its core: “portentous signs,” Tillet wrote, of “revolutionary tendencies.” Here was the first sip of potential; on the tongue it was very sweet, and tasted a lot like power.

IV.

To those who feared the workers of Britain, the summer of 1911 seemed never to end. For those who fought in the heat and dusk of an entirely unexpected rebellion, their bright hope was that the carnival might last forever. Every demonstration, every picket, every roar of the mass seemed larger than the last, and each week a new link was forged between trades and grades, between women and women and men and men, the new spirit cracking into industries once thought immune and impregnable. In an ominous turn, the government, paralysed and bewildered, was abandoning the patience of George Askwith for the blunt techniques of the army. Surge and retreat, the tide receding then coming in just as quick: a workers’ victory was not a peacemaker or a balm; their defiance was kept in reserve, cool and ready. At the overlap of each dispute, new dominions bloomed.

The basic gospel of solidarity was contagious; Liverpool proved it. The city’s dockers had joined the rest of the country in July, won their demands, and returned to the ports. Yet that strike had caught the attention of the railway workers who lent a hand by refusing to load scab goods. Their boycott led to the formulation of their own grievances and when, in early August, the drivers, shunters, firemen and signalmen started to walk out (again, contrary to their union leaders), the dockers paid back the favour and struck in solidarity. These roiling, undulating actions in Liverpool split into two separate but connected campaigns: a city-wide transport strike and, within a week, a national railway strike.

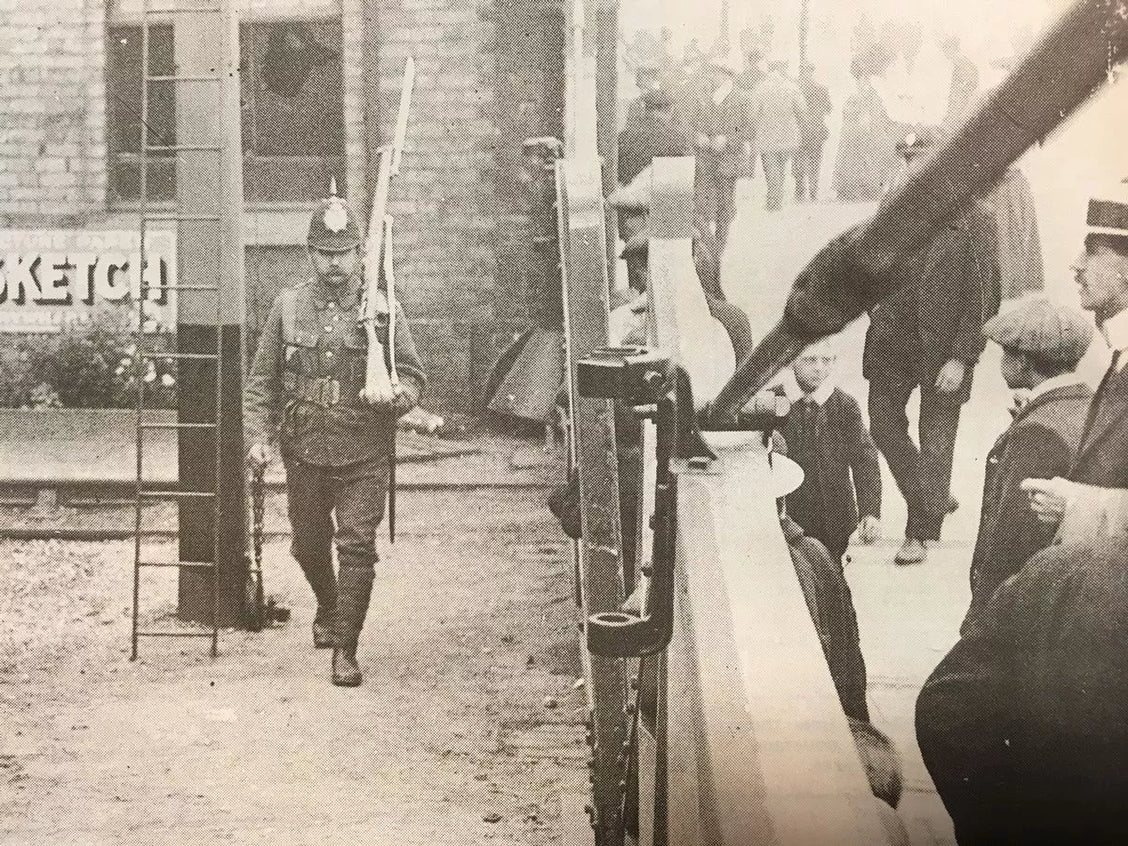

At its epicentre, as ever, was Tom Mann. Some 80,000 people poured onto St George’s Plateau on August 13th to hear him speak – the largest rally ever held in the city. They came from Toxteth Park and Everton and Scottie Road, and waiting – batons in hand, a sneer on their faces – were the restless reserves of the city’s policemen. Bloody Sunday (350 injured, nearly a hundred arrested) set off two nights of rioting. In Christian Street workers spun barbed wire across the road and built a barricade of dustbins. When a crowd of thousands tried to free Sunday’s prisoners from a convoy bound for Walton prison, the guards let loose their rifles, killing two and injuring fifteen others. Liverpool’s transporters ceased work: a total standstill save for the trickle of cargo allowed to pass by the permit system. Sat squat in the harbour the armoured cruiser HMS Antrim traversed its guns over the mouth of the Mersey.

“Your liberty is at stake. All railwaymen must strike at once. The loyalty of each means victory for all.” This was the message, printed on 2000 telegrams, sent out by the heads of the four main railway unions (ASLEF, ASRS, GRWU, UPSS) on the night of the 16th. At 5pm the next day, nearly 150,000 rail workers were out; another 50,000 the next. At Portishead, Derby, Lincoln, and Chesterfield, strikers attacked signal boxes, set fire to depots, tore up tracks, cut telegraph wires. Barraging a picket crowd with rifle fire, soldiers killed two men in the Welsh town of Llanelli. Locals had their revenge by burning down the depots and looting carriages belonging to Great Western. A furious Keir Hardie told parliament, so used to the muffled taciturnity of its members and unfamiliar with direct truths, that the dead of Llanelli “have been murdered by the Government in the interests of the capitalist system.”

Troops dotted the tracks. Sentries stood with locked bayonets outside every major station in every major city. Generals directed whatever traffic remained on the lines. Hyde Park and Battersea Park became barracks – and who knew how temporary they might be? At the Home Office, Winston Churchill – shimmying quickly backwards out of his brief period as a Liberal and a radical – vibrated between total despair and a grapeshot attitude. At one moment he could suspend army regulations, allowing him to unilaterally call out 50,000 soldiers; at another he would throw back that wobbly, jowled head and moan: “The men have beaten us…There is nothing we can do. We are done!” George V, that demure new monarch with the personality of a small rock, was much clearer in his opinions. The troops, George told Churchill, should be given “a free hand” so “the mob should be made to fear them.” Things were beginning to look “more like Revolution than strike.”

The King was soon disappointed, as all kings should be. The rail unions, meeting in continuous joint session in Liverpool, had only declared the strike official to gain some kind control over what the rank and file had made a certainty. As soon as the union leaders were in a room with the not-very-frightening figure of David Lloyd George, they surrendered. The strike lasted just three days, and the terms of their capitulation were no better than what had been offered when they sent out their rousing telegrams. Churchill phoned Lloyd George when the deal was announced. “I’m very sorry to hear it,” he grumbled. “It would have been better to have gone on and given these men a good thrashing.”

It is easy to imagine the Labour Revolt being choked in its crib if only the Liberal government continued to listen to Askwith. With his knack for keeping the peace and forcing parties toward what looked like common ground, he was a formidable foe to the militant. Yet ministers kept sailing over Askwith’s head, grandstanding as they went, lacking his grasp of demands and details – or even the most basic understanding of what a union was built to achieve. Until the summer of 1911 the strike wave had been decidedly non-political: aside from the scattered syndicalists around Tom Mann and the Plebs League there was little rage directed at the Liberals who, it shouldn’t be forgotten, most workers had voted for three times since 1906. Yet every intervention made by the government, always on the side of the owners and employers, transformed the tone of the rebellion. If the prime minister HH Asquith, Lloyd George, and Churchill experienced the prewar years as nothing more than a cascading stream of crisis and disaster, it was entirely their own fault. And whatever victories Liberalism claimed for itself turned out, beneath Lloyd George’s populist smugness, to be a frustrating interference in working class lives. The National Insurance Act of 1911 imposed a tax on the working poor, and with the tax came a new bureaucracy with its cold, callous and patrician character. Expecting gratitude, the government got resentment. To the workers’ list of enemies was added the political class.

A revenant: from the ruins of the miners’ defeat in South Wales came a new demand, compounded like a diamond underground and sent smuggled in the pockets of “missionaries” to Durham and Northumberland and South Yorkshire. The Miners’ Next Step, likely written by Noah Ablett, called for a “united industrial organisation…constructed on fighting lines.” In February of 1912, and despite the Miners’ Federation trying to jilt the vote by requiring a two-thirds majority, a crushing eighty percent of all unionised miners made their plea: a national minimum wage for all subterranean workers of five shillings an hour for men and two shillings for boys. Bold and undaunted, the miners prepared an extraordinary strike for their “5 and 2”.

[book-strip index="3"]

On February 27th one million miners came out and set their pickets. Confronted with a nation about to stagger and stall, deprived of its precious fuel, the government blundered its way in. The guileless and serene prime minister Asquith scolded the Miners’ Federation by reminding them of “the great mass of people…whose livelihood, comfort, welfare, even existence, very largely depended upon you.” Which was the whole point. With one hand the Liberals tried the whip: ordering Tom Mann arrested under the Incitement to Mutiny Act, passed in 1797 to root out sympathisers of the French Republic, for publishing an open letter urging soldiers not to fire on their own as they had done at Llanelli and Liverpool. With the other hand they tried a treat – though it was a peculiar and parliamentary kind of bribe: a bill forced into the Commons which contained the principle of a minimum wage but was empty of the miners’ key demand of the 5 and 2. Unable to endure even the most delicate pressure from the workers, Asquith clutched the despatch box during the third reading and wept.

In early April, with the minimum wage established in law, the MFGB leadership overturned a narrow majority of its members who wanted to continue the strike and ordered a return to work. The union had, after all, humbled the parliament of the largest empire in the world and made its prime minister cry on the floor of the house. In the next two years its membership would balloon by another 200,000. Yet wasn’t there something unsatisfying about the conclusion of the saga which began with seventy men at the Ely colliery and which had its potential spent and wasted by cabinet ministers and union heads? Like so many other workers, the miners had realised all at once the scale of their struggle and saw for the first time, and clearly, the true face of their foes. Such a stark glance at reality did not intimidate them; it gave them strength.

Beneath the banner-headline, actions roiled a spree of smaller lockouts and tool-downing, walkouts and wildcats no less rancorous and radical than those in the major industries. Perhaps a hundred workers at a time, or a thousand – men or women, often both – struck from modest factories and town workshops, spreading even to schools and music halls. Between 1910 and 1913, by Darlington’s calculation, there were 3,788 strikes; almost 73 million working days ‘lost’. Weavers and farm labourers in Lancashire went out, as did Cornish clay-haulers. Cab drivers and hotel staff in London organised (including at the Savoy, where management withered at the mere mention of the word “strike”). The Workers Union representing engineers of all grades and genders (founded, once again, by Tom Mann) fought a campaign against metalworking bosses in the West Midlands from the winter of 1912 through April of 1913. In a demonstration equally charming and horrifying, some hundred children “employed” in the printing office of the Bank of England threw out their types and walked off the job. At the Singer sewing machine plant in Clydebank, women organisers tried shop committee techniques pioneered by the IWW. The Jewish tailors of Whitechapel fought a three-week battle and won. At Victoria Docks near Canning Town, during a doomed attempt to repeat the NTWF’s victory in London, strikers and scabs fought a gun battle aboard SS City of Colombo. Leith saw a campaign of walkouts, nights of rioting, bombs placed like potted hydrangeas at factory walls, and gunboats in the harbour.

V.

William Martin Murphy was the owner of the Irish Independent, the boss of the Dublin tramways, and “Catholic Ireland’s most powerful capitalist” as Darlington puts it. In him was contained all the stupidity and incoherence of the Liberal era. He could be, on the one hand, an ardent Home Ruler, and on the other a vicious union-buster. A quick glance over his record would seem to show an equal hatred for Edward Carson and for James Larkin, yet in the summer of 1913, as the Ulster Volunteer Force drilled its militias and plotted an operation to run guns in from Germany, Murphy chose to sink his well of animus in a campaign to destroy the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union.

All struggles are in some sense existential: between a worker’s self-interest and the institutions of the nation which instruct her to keep her head down and just get on with it; between the burdened shop floor and the cruel whip-handed manager; between the mass of a workforce and the weapons of industry. No matter how small or large, each confrontation is a fundamental plea for survival, yet its starkest colour is rarely seen in full. With the protection and approval of Westminster, the police, and the army, with four hundred other city employers at his side, Murphy let loose his total war against Larkin and the ITGWU. The Dublin Lockout showed how far along things had gone in just a few years, how drastically the terrain of battle had shifted. No longer would bosses and owners resist their workers for the simple end of retaining a right to hold down wages; Murphy and his kind embarked on a counteroffensive to vanquish the very idea of trade unionism. Here was what the past two years had been leading towards – a revelation of sorts, a theory made real and literal: the undisguised combat of class against class.

By the end of September, the lockout was general. Some 25,000 Dubliners were out of work, two of them were dead and hundreds more with their heads split open under the rampages of mounted police, and still Murphy and his ilk hummed like a team of Cheshire cats, offering the workers a simple course of action. To get back to their jobs, to feed their families, all they would need to do is renounce any membership, affiliation, or sympathy for the ITGWU. Dublin held its nerve. To keep the ports open, Murphy asked the Shipping Federation (the mercenary club of strikebreakers operated by the cargo companies) to ferry scabs into the city. “The ITGWU was confronted,” Darlington writes, “with a prolonged battle of attrition designed to bleed away its resources, both financial and moral.” In the pallid face of Murphy’s radical escalation, the only choice left for James Larkin, with his “divine mission” to make “men and women discontented,” was to counter-escalate. The union’s organising capacity had to be transformed into an ad-hoc civil service for the preservation of working class lives through the distribution of clothing and food; workers willing to risk their blood against the state had to be armed (Larkin: “My advice to you is to be round the doors and corners, and whenever one of your men is shot, shoot two of theirs.”); above all, there would be no victory against Murphy without the solidarity of the British mainland.

The ITGWU’s tradition since the beginning of the Labour Revolt was to boycott tainted goods coming from over the Irish Sea. Now it expected the favour repaid. Through September and into December thousands of transport workers from Birmingham to Crewe to Sheffield “blacked” cargo bound for Dublin, while dockers in Liverpool, London, and Salford stuck to the same principle. If sacked for their refusal, they could depend on their friends to walk out until they were reinstated. Over 300 branches of the newly amalgamated National Union of Railwaymen passed a vote of no confidence in their own leadership for tolerating the transit of scab goods (and scabs themselves), many of them demanding an emergency meeting to consider the possibility of joint action with the miners and transporters. To complement the ground campaign: a civil movement for Dublin’s relief consuming the whole constellation of leftwing movements. A donation drive backed by the Trades Union Congress and the anti-sectarian Daily Herald took in £150,000 (around £18 million today) while the SS Hare was chartered to deliver critical supplies of tea and butter and jam to the encircled Dubliners. A second rally at the Albert Hall a fortnight after the mammoth meeting at which George Bernard Shaw made his suggestive appeal for armed action also breached the theatre’s capacity – one link in a string of demonstrations spanning Bristol to Edinburgh.

Even if they resisted calling themselves as such, even if they did not realise it, by engaging in solidarity strikes, by sneering at the yellowness of their union heads, the British rank and file were engaging in the emotions and tactics of syndicalism. And how fitting that in this year, 1913, Emile Pataud and Emile Pouget’s Comment nous ferons la revolution (How We Shall Make the Revolution) should be published in English as Syndicalism and the Co-Operative Commonwealth with a foreword by Tom Mann. But where was Tom Mann? At the critical moment, when his presence might have made a real difference, Mann was in America, unable to bend the union bureaucracy to an official policy of backing Larkin to the hilt. The rank and file were demanding a general strike, the Daily Herald was demanding a general strike, yet the TUC was determined for its charity to be the upper limit of support for Dublin’s embattled labourers. It was Ben Tillet of all people – the reluctant figurehead of the London dockers two years earlier – who proposed a motion condemning his comrade at a TUC conference in early December. By an eleven-to-one vote, the TUC refused to sanction sympathy strikes. Larkin had his small revenge: the union chiefs, he said, were traitors to their class with “neither a soul to be saved nor a body to be kicked.” By the end of January, Dublin lay prostrate before William Martin Murphy and his friends.

[book-strip index="4"]

What the years of the Labour Revolt had so far taught the workers was this: even in the most acute moments of crisis, when they held in their worn palms their own existence and all that was taken for granted at the dawn of this deceitful new century, the people who were supposed to lead them were caved to the mysteries of good taste and the funhouse-mirror of working class respectability. In this sense, Darlington suggests, the rank and file might have been the victim of a great success. By fighting so hard to organise, by demanding recognition in their workplaces, the labourers threatened to fall into a bureaucratic trap. Once inside the union, they were bound by the discipline and authority of those leaders who gagged at the idea of radical change, who treasured the fetish of negotiation, who coasted to power on a soft and placid platform that had no need for stronger methods. Yet if the workers had already rebelled against these tendencies they could do so again, having conclusively proven in fight after fight that their own conscience was a better guide than those above. As Darlington himself agrees, the rank and file were the “central motor,” with a “remarkable ability at critical junctures to overcome the inertia or compromises of the official union leadership.” Another of those critical junctures was fast approaching.

Just as Lloyd George and Asquith’s dogged determination to muck about in a field about which they knew nothing made the labour revolt an explicitly political revolt, so the intertwining of the workers’ struggle with Irish demands for liberty (and the Tory promise to deny it) deepened the pallor of the crisis. The Irish cause, Darlington notes, had been “carried into the heart of the British labour movement,” and by appealing to the mainland for support, by conscripting the Shipping Federation and the TUC to the fight, both Murphy and Larkin sharpened the pitch of the crisis and introduced an imperial aspect to the battle – a battle that might at any point become simultaneously international and fratricidal. The battle fought in Dublin and over Dublin had the good fortune to arrive just as the Carsonites and Tories in Ulster were leaning full-in to insurrection, making armed action in one field all the more likely in another. “Any attempt to break the loyalists of Ulster by the armed forces of the Crown,” the Daily Telegraph prophesied, “will probably result in the disorganisation of the Army for several years.” And what became of Larkin’s self-defence force, those jobless, bootless men clutching hurleys on the fringes of protest meetings? They were recomposed under James Connolly’s watch, armed with Mausers, and called the Irish Citizen Army. These facts troubled Lloyd George more than any other; even though he had helped by his blundering to bring it about, he still had the foresight to notice that if “insurrection of labour should coincide with the Irish rebellion…the situation will be the gravest with which any government has had to deal for centuries.”

VI.

What began in South Wales and Cradley Heath did not end with Dublin’s defeat. The new year beckoned with a gleam of promise. The number of strikes between January and July of 1914 was only slightly smaller than in the entirety of 1912. Miners in Rotherham spread a strike to the rest of Yorkshire’s pits; women in fisheries and canning plants in North Shields and Millwall went out, as did laundresses in Liverpool; London’s construction workers fought a lockout modelled on Murphy’s methods in Dublin. Though the London builders lost that battle, at no juncture during the Labour Revolt did a beating handed down from the bosses imply an instant and general retreat from radicalism. The movement was rarely (if ever) overcome by reticence or resignation. A win, a half-victory, even a total capitulation generated more fervour, the rising popularity of syndicalist tactics, louder calls for unity.

It was this same refusal to bow, this enduring sneer from the ranks below and a ceaseless stream of demands for a common front which pitched together three of the largest unions in the country in the spring of 1914. The miners (MFGB), transporters (NTWF), and railwaymen (NUR) held a conference in April which formalised the creation of a Triple Alliance; by July a draft plan was proposed suggesting (per Darlington) each union arrange their collective agreements so that they all terminated at the same time. Each body would simultaneously submit its own demands for improvements in pay and conditions, and agree they would not settle unless the others had also reached agreements. On this basis it was hoped either the employers would give way before the massed industrial power of the three groups, with no strike needed, or if a strike did occur all three industries would be stopped at once…

So vast an undertaking, with such awesome potential, the Triple Alliance was destined to be misunderstood by those who had made it. Union officials of a conservative nature saw in the pact a method to finally discipline the rank and file, to keep unsanctioned action in check. In the draft agreement each union had its own right of veto and could unilaterally withdraw at any moment. For these labour pacifists, the best kind of general strike was one that never had to be called; it was better to raise the possibility of one without ever fulfilling its promise. The militant masses, newly arrived in the union movement, saw no point in an alliance if it was not used to violent and persuasive ends. Indeed, the militancy of the workers was resistant to pleas of patriotism and national obligation. Less than a week after a Habsburg heir was shot in the Balkans, 12,000 munitions workers at Woolwich Arsenal went on strike after a colleague was sacked. These methods, surgically cleaving to the very core of the nation’s concept of its own greatness, were “far less of a haggle, far more of a display of temper,” HG Wells observed. “New and strange urgencies are at work in our midst, for which the word ‘revolutionary’ is only too faithfully appropriate.”

The gathered waters receding before the tempest. Wait till autumn. Wait till autumn. This was the phrase which crept around lodge halls and drawing rooms, setting a chill in the necks of the bosses and a giddy flare in the eye of anyone who could guess at what might come. The Fabians warned of “an almost revolutionary outburst” (that “almost” is a very Fabian word). George Askwith, the Board of Trade negotiator, was better placed than anyone to notice the confluence of events. “That the present unrest will cease I do not believe for a moment,” he told an audience in 1914. “It will increase, and probably increase with greater force,” driven by a “spirit and a desire for improvement, of alteration.” There could be “movements in this country coming to a head of which recent events have been a small foreshadowing.” In his memoirs, Askwith recalled a “general spirit of revolt, not only against the employers of all kinds, but also against leaders and majorities, and Parliamentary or any kind of constitutional and orderly action.”

For all his caprice and prejudice Winston Churchill was not a witless man, and he had nerve enough to spot as early as 1911 the tributaries flowing into the “grave unrest” of a “general strike.” Yet after four years of unrest the government could claim no victories of its own. At every stage Churchill, Asquith, and Lloyd George failed miserably to negotiate any kind of settlement save that of the manner of the deaths of those workers they ordered shot in the street. It was the bosses who secured for themselves a paltry handful of wins; it was the conservative union heads who stifled more expansive actions. The government was – as with the very idea of Liberalism itself – helpless to halt pressure from below. The chief of detectives at Scotland Yard suggested Britain was “heading for something very like revolution.” Unless, he added, “there were a European war to divert the current.”

History is much like a basin: everything streams into its making. Sometimes, however, the torrent is dammed shut and the deluge slaps against itself. It is a sad and bitter fact for the ruling class of the nation, forever a stain on their names, that they had to be rescued from the beckoning arms of a revolution not by their own skill or breeding but by the grotesque horror of the First World War. The Second British Revolution died under the guns of Marne and whatever potential existed at the dawn of August “slipped away,” as George Dangerfield once wrote, “into the limbo of unfinished arguments.”

Anyone wishing to understand the crisis which very nearly defeated the British state in these years will inevitably have to confront Dangerfield’s magisterial work The Strange Death of Liberal England, first published in 1935. Dangerfield’s gifts were those of a particular kind of British writer long since passed, possessed of the novelist’s ear for secret melodies and a voice shining with salt ripples of sarcasm, and he took the likelihood of a revolutionary moment in autumn or winter of 1914 to its outermost extreme. Ever since, Dangerfield’s louche hand has continued to rise from the past to prod the flabby undersides of starchy academics who have never stopped letting themselves be annoyed by his talents. The welter of praise has been equal to the number of humourless pedants and helpless tenurists who keep trying to have their revenge on the book – poking holes in its facts while never arriving at an obvious realisation: even if wrong in detail, the wider thrust of its method and style arrives closer to a more penetrating truth. Counterfactuals are often fantasies disguised, yet as Dangerfield noted, “History has supplied the premises, and if the propositions to be discovered at the end of them are fantastic, at least they have the merit of being logical.”

Ralph Darlington does not sneer at Dangerfield (though he does describe him as a “journalist” rather than a Pulitzer-winning historian), but he is much more sceptical in his assessment, much more reticent in his conclusion. “Militant currents,” Darlington writes, “were no more unified in organisation or action than the working class as a whole,” and there was “insufficient unity of purpose between the disparate labour, Irish Home Rule and women’s suffrage movements to enable them to make common cause.” Darlington’s judgement of working-class strength and self-awareness in the summer of 1914 may not have been the same as their strength come the fall, and it is entirely possible that a revolutionary situation can fall on its combatants without them ever being aware of it or desiring it. Whether they intended to or not, whether they were ready for it or otherwise, the militants of the Labour Revolt were approaching an insurrectionary moment, and that moment would decide the future, not their own individual attitudes. And in the case of the triple-threat – Irish republicans, feminists, workers – a common cause had been established at the Albert Hall on November 1st, 1913, an awareness which, come the autumn, might have taken a formal shape. And each struggle at various points between 1910 and 1914 had accelerated the crisis regardless of whether they were holding hands. But cease the thought there. We are all, with varying quantities of enthusiasm or cynicism or nostalgia, entering the gorgeous realm of free speculation – all reading, in Dangerfield’s evocation, “a mere fragment of a play, with the last act unwritten…

Time, indeed, decided the question otherwise; but the most insidious of all the enchantments of history lies in those parts of it which cannot be written, where the premises are only given, and their implications may be followed any way one pleases…These events have expired, unborn, in the enormous womb of history, and we shall never be sure.