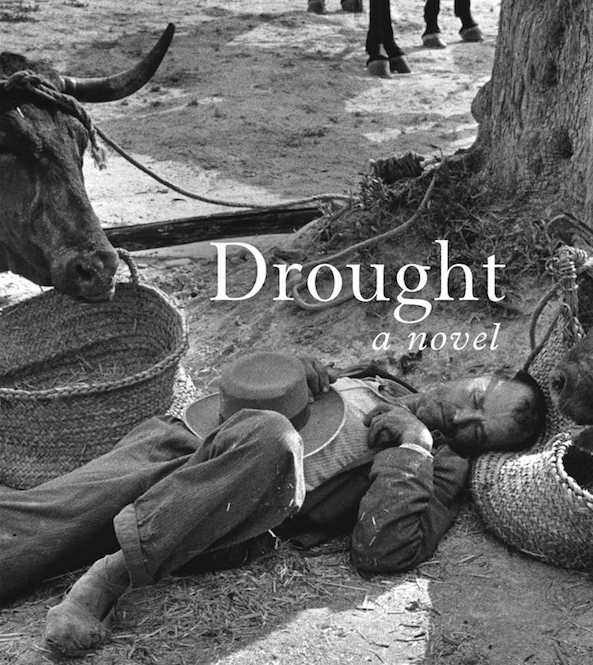

"Scalped to the bone by the heat and drought"—an extract from Ronald Fraser's novel Drought

The below is an extract from Drought: A Novel, by the eminent oral historian of Spain Ronald Fraser and recently republished by Verso.

This extract follows British journalist John Black, recuperating in the arid, parched Andalusian village of Benalamar, one that is almost untouched since the end of the Civil War. It is a community reeling from the death of a local farmer, Miguel, who killed himself ostensibly over access to the vast reserves of water that are spilling uselessly back into the ground that could otherwise sate the community over the long, hot summer. Amongst the turmoil, a foreign businessman arrives into the village with plans to save the day...

10 September

Perhaps Bob is right, perhaps it’s becoming an obsession. If I hadn’t known Miguel, if he hadn’t come up to ask for help, this past would remain a perpetual, indifferent present. But now the present has reordered the past, given it new meanings. Like Suez. That’s what Pavese’s phrase really means. My life has come out of books; the written seems more real than what I live. Bob isn’t like that, I suppose it’s what I admire in him. But now he feels I am obsessively betraying the past, one he thought I shared with him. I can’t help it, I have to know.

Had I been more aware, I see now, there were things I could have understood then, but they seemed to make so little differ- ence: a pitcher of water a day which Dolores fetched, which was in its place under the washstand, I didn’t need more. Water, I remember, to be taken for granted, like the hills and the heat, like the hole in the square we peered down one morning in early June, the men who had gathered at the news making way for the two foreigners to look, as though eyes could tap the source in the mountain and restore the flow. So this was where the water had come from, this hole under the slab I had so often crossed on my way down to see Miguel, and now, as mysteriously, no longer appeared. We crowded round uselessly to look at the echoing tunnel whose rough-hewn dry walls were already warm, the men’s faces worn as though the earth had got under the skin. And then someone said:

‘They’ll deepen the borehole.’

And another: ‘What’s the use, this one has always given out.’

And a third: ‘It’s the señorita’s new borehole that’s taken the water.’

‘Hombre! She hasn’t hit water either.’

All round us their voices came in short, heavy bursts; they didn’t move when they spoke. The sun was full on the square, on their threadbare cotton trousers and shirts, their earth- coloured sombreros. As though simulating a passion to break the dead hours of waiting for work, they repeated the same arguments again and again. There was nothing to be done. Water, or the lack of it, were facts of nature, immutable.

Idly my mind turned to Miguel. He had been right, the water hadn’t lasted, I wasn’t going to see the terraces flowing with water again.

Bob took my arm, leading me clear.

‘Well, that’s that, isn’t it?’ I said. ‘That’s the end of the dam.’

‘No. Look, there ’s the other borehole, the one that bloke – what’s his name? Miguel, that’s right – told you about. I’ve been out there to look at it. They didn’t hit water as quickly as they expected, and they’ve run out of money. A lot of the owners, including María Burgos, wouldn’t put any more money in, so the drilling has stopped. I’m going to see about it.’ In a few quick strides he was across the square, calling over his shoulder, ‘Stop by tonight,’ and for a moment, watching his broad-shouldered figure disappear, I was moved by his unquenchable spirit. Ah well, he had his reasons, I thought, his land, a house to build …

I turned to go, an unfinished page waiting for me in the granary. Crossing the beaten-earth square, I recalled my arrival three months earlier by taxi, a 1929 Buick that bounced and groaned its way up from the coast and finally steamed to a tri- umphant halt by these bitter orange trees. In Torre del Mar, on the coast, a few English were living; I’d no desire to be another exile among them and was leaving after a few days. It was early March but the sun already seemed to have the weight of summer.

Cursing the potholes and a foreigner’s whim, the driver’s sole exclamation of pleasure, more to himself than to me, came at the sight of water foaming down the side of the dirt road, where figures in black, bent over their washing, stood up and stared, following the car’s slow ascent, and children and dogs rushed out of a farmhouse. I followed the water, like quicksilver in the sun, seeing the two Guardia Civil in their black tricornes and uniforms the colour of the agave they stood beside, turning their heads slowly in the cloud of dust to watch as the taxi took a curve. And there, opening below, was a bowl of earth, cross- hatched with furrows, where a man stood staring up at the road. Behind was a white farmstead, like all the rest, and a hill with three umbrella pines. It might have been Miguel, though I can’t be sure, I was looking more at the earth than at the man. A half dozen more curves and suddenly, like a vision of Braque, the village appeared – a series of dazzling white cubes and sienna- brown tiles piled at random angles up the sides of a hill that rose steeply to a ruined fortress or church at the top. I gasped. Beyond, range upon range of mountains etched in vermilion and shadowed blues against the afternoon sky.

The taxi plunged into a narrow cobbled street, there was a flow of white and sunlight ricocheting off walls, the sudden glimpse of jasmine in a darkened patio, a figure in black caught in the sun, and then the curving down to the square where pools of shadow lay under the orange trees.

Dazzled by whiteness and a sense of enclosure as people gathered round to stare, I was disconcerted to see an English face push through the crowd. ‘They don’t see many cars up here,’ an unmistakably North London voice said. ‘And even fewer foreigners.’

He picked up my typewriter and led me into the bar. His square-cut features, the chin especially, and the broad nose made me think of a boxer; his eyes were a very pale blue, slightly sharp. He was evidently at home in the bar, and two beers and tapas of some undeterminable meat appeared instantly. He asked where I was from, and said he came from Camden Town, a surveyor turned estate agent who’d done well, so I was led to understand, out of the recent property boom. Camden Town was coming up. ‘But I’ve had enough. A bit of the quiet life is what I need now. I’ve bought some land here, got it pretty cheap, and I’m going to build myself a house.’

And I, thinking the light in the bar was like weathered wood, taking in the faded Manolete poster, the Mono adver- tisement, the dusty hams hanging from the beams, only half listened. Everything seemed covered in an air of fragrant des- uetude and freshness at once. For the first time since leaving London I knew I had chosen right. I looked through the door to where two or three men sat in pyjama tops and others stood in the shade of the wall, saw the white walls broken by barred rectangles and squares, felt the world dropping away in the afternoon sun.

My thoughts were interrupted by his asking if I had some- where to stay. No, I confessed, taken aback by my lack of prevision. Well, he could fix it. He called the bar owner and began a rapid-fire negotiation. ‘Can you make ten bob a day? Yes. OK. You’ll like this house, needs a bit of doing up, bit primitive, but you won’t get much better here. Come on …’

And so, thanks to Bob, I found myself in possession of two furnished rooms, the granary, a waterless, seatless lavatory in a bare room large enough to swing several cats, and a kitchen. It was the granary that won my heart, and I quickly moved in a table and chair and set up my typewriter. My happiness at being so rapidly installed was mixed with a measure of irritation at being immediately indebted to Bob.

The next morning Dolores appeared; again, Bob seemed to have made the arrangements, if I understood her correctly. I determined in future to keep to myself; with the start of the promised self-examination, I had plenty to occupy me.

A week or so after my arrival, he dropped in. ‘Haven’t seen you around. What’ve you been doing with yourself?’ I mumbled some excuse. ‘Well, come up for a meal tonight. You know where my place is? Last but one house.’

I had no ready excuse and that evening I found myself sitting on the terrace of the old house he had rented, more spacious, though not better equipped, than mine. I thanked him for finding me Dolores. Bob laughed.

‘Does she come on her own? Yes? Perhaps they’re getting used to us.’

He’d been hard pushed at the beginning to find anyone, he recalled: it was almost impossible to get a village woman to work for a man on his own. Until his wife came out, his cook always came chaperoned by a young girl. So he ’d taken the trouble of asking his cook, who had persuaded her cousin Dolores to take on the job. ‘Now that June’s gone back to London for a visit I half expect to see the chaperone turn up again.’

He refilled my glass and began to describe the house he was planning to build. Water was one of the main problems. At the moment there was plenty and it ran to waste in the watercourse because no one was irrigating – it was, as I’ve said, not yet quite spring. But for three or four months in the summer there was never enough. It was scandalous. ‘I can’t understand why they don’t do something about it. Eight months of waste and four months of shortage. And this has been the third dry winter in a row.’

At that moment the men carrying bales of brushwood on their heads started to come by. Narrowing, Bob’s eyes watched this strange and pitiful procession bent so low under the weight that only the men’s feet dragging in the dust showed. We had both seen it before and yet it never failed to leave its mark. I knew such poverty existed, had even written about aid to the Third World, but I’d never seen it until coming here, that was the difference.

‘You know how far they carry that wood?’ Bob asked, break- ing the silence. From the top of the mountains, three hours’ walk. And as if that wasn’t enough, they had to hawk the fire- wood from door to door when they got to the village, often forced to exchange it for a bit of bread. For a while, until the last man had gone, there was silence again.

‘We were poor, I remember that as a kid before the war,’ he said suddenly. ‘My father was out of work a lot of the time. Still was when I went into the RAF in 1940. We didn’t have that much to eat, but it was never like this.’

For a moment I hoped he would leave it at that, but he went on, talking of the men who stand uselessly in the square waiting for work that never comes; of the carriers running fish up from the coast in sacks strapped round their foreheads; of men who are beaten up in the Guardia Civil barracks for gathering wild esparto grass in the mountains to keep themselves alive – esparto that a well-known falangist in the town claims as his private property …

He glanced at me; I saw now that the day when, on an impulse, I disembarked in Gibraltar from the Alexandria-bound freighter, I hadn’t given a thought to the present. I felt better and I’d had enough of the sea, the cramped quarters, needed to feel land under my feet again. And it was the past of the civil war that had once interested me …

‘Living here brings you up short. Did you hear what Macmillan said the other day? We ’ve never had it so good in Britain, he said. No thanks to him and his Tories, it was Labour, the Welfare State we can thank for that. It’s something I’ll never forget, the first time I voted. They could do with a bit of that here.’

In the last evening light the land fell away in front of us: scattered terraces of barley and alfalfa shone green among the soft, barren hills, and isolated trees were in flower along their edges. If all the land were as fertile as those terraces, Bob said. And why not? The water so arduously mined from the mountain, in the way learnt from the Moors, was wasted, not conserved

… With enough water there ’d be enough work – and suddenly surging forward into the idea of a reservoir, Bob carried me on into valleys green with alfalfa, covered by fruit trees, rich with cattle, where there would be work for all. An end to drought. His eyes shone with the vision; this dry, cracking earth made green, farmers exporting their crops; and he – no, now it was us – in this swollen dream surveying the meaning of our pres- ence here. A revolution of water and work; the desert blooming in a joyful Swiss scene that was darkened by an uncomfortable thought: hadn’t he just shown me a model of his house, hadn’t it a waterflow through it? A gallery with a fountain, a pool?

He smiled. ‘That’s right. What gets done in this world without a bit of self-interest? It’s human nature after all.’ But he wouldn’t need a tenth of the reservoir, the rest would go to the farms. ‘Twenty-five million gallons. The watercourse goes through my land, and I’m going to build a dam. It’ll put an end to this stupid situation, help the people to help themselves. It’s a good investment all round, good for the village, good for everyone.’

Struck by the logic of it, infused by the dream, I couldn’t help then but agree. Yet simultaneously a nub of doubt formed; Bob’s frankness about his motives was perhaps a little too frank for my taste, but this was of less concern than the fear of allow- ing myself to get carried away by schemes that would distract from my self-examination. For all my expressions of agree- ment, I knew that I wouldn’t fully involve myself in his plans. I wasn’t capable of sustaining his sort of vision. As usual, I’d be an observer.

- Images are courtesy of Libcom.org