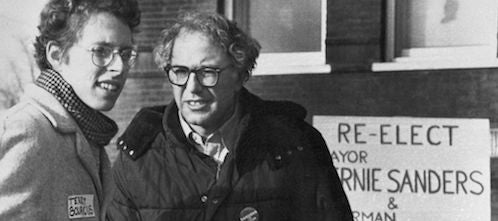

Bernie Sanders and the Rainbow in Vermont (1990)

This 1990 essay by long-time Vermont labor organizer and activist Ellen David Friedman examines Bernie Sanders' first decade in office and the wider context of independent and Rainbow Coalition electoral politics in the state. First published in The Year Left Vol. 4: Fire in the Hearth - The Radical Politics of Place in America, edited by Mike Davis, Steven Hiatt, Marie Kennedy, Susan Ruddick, and Michael Sprinker.

The electoral landscape in Vermont has seen some dramatic changes in recent years. These include the Democratic takeover of all branches of state government and the landslide re-election of prominent liberal US Senator Patrick Leahy in 1986. To the left, there have been the nationally unparalleled four-term mayoralty of socialist Bernie Sanders in Burlington, the succession of this seat of independent progressive Peter Clavelle in March 1989, and Sanders’s near-miss run for Vermont’s single US House seat in November 1988. There is also the surprising strength of Jesse Jackson's performance in 1984 and 1988 and the continuing activity of the Rainbow Coalition of Vermont (RCV) in supporting progressive legislative candidates. Both the mainstream and left press have found this transformation of the “rock-ribbed Republican” backwater state into a liberal/progressive bastion an interesting phenomenon.

But for American socialists, the lessons to be learned from these developments are far from simple or definitive. There are, as in any situation, important local features (such as, in this case, the racial uniformity of the population, the lack of a developed industrial base and working class, and the historical absence of organized labor interests) that make our experience different from those outside Vermont.

But there are also some aspects of our experience that should be useful to anyone experimenting with left electoral strategies. Most important, there are some sharp questions that our experience allows us to examine from the basis of actual practice: what can the left take from its experience in mass-based issue organizing to the electoral arena? Can a strategy of working inside and outside the Democratic Party (proposed by Jesse Jackson and tested nowhere else so thoroughly as by the Rainbow Coalition of Vermont) really work?

Unlike some other states, Vermont has never had a strong left presence in the Democratic Party. For fifteen years there has been a consistent string of third party efforts — beginning with the Liberty Union Party in the early 1970s (with Bernie Sanders as one of its founders and regular candidates), to the Citizens Party (which had its first electoral success in Vermont when Terry Bouricius was elected to the Burlington City Council in 1981), and, currently, through the Progressive Coalition in Burlington (the organization, though only recently constituting itself as a party with caucus and nomination mechanisms, that has supported Sanders and the independent City Council members for the last seven years). These efforts have been propelled by progressive activists, generally operating with a class analysis, but not affiliated with national left parties. Their disdain for the Democratic Party was generally unequivocal.

The early impetus for and continuing strength of this trend drew on the migration of East Coast student radicals and counterculturalists to Vermont, beginning in the mid-1960s and not slacking until the late 1970s. There was a natural draw to this pristine, rugged and wide-open rural state for young people who gathered in their hands the various threads of environmentalism, “back-to-the-land” self-sufficiency, antiauthoritarianism, mysticism and hedonism, and — in strong measure — a social utopianism fueled by rejection of the corrupt imperialist infrastructure that seemed, at the time, about to collapse. The busyness and fervor with which new structures were created at this time can barely be measured: collectives and communal farms, food cooperatives and health food stores, day care centers and alternative newspapers, and above all, political study groups and activist organizations and political parties that took their energetic charge from the antiwar movement and acted on the powerful impulse of the time to build a progressive alternative in the “belly of the beast.”

The Liberty Union Party, successful even at a time when electoral politics was distinctly out of vogue with radicals, gained major party status in 1974 (this status is granted and retained in Vermont to parties that capture at least 5 percent of the vote for any statewide candidate), and maintained it until 1988. A party of explicitly anticapitalist ideology and addressing itself to the survival issues of poor people (utility rates, health care, housing), it supported the candidacies of some superbly smart and articulate radicals. But by the beginning of the 1980s it had lost its leadership (including Bernie Sanders), and ultimately its ability to mobilize to its base of support.

Independent Politics

By comparison with the rest of the country, an independent left approach to electoral politics in Vermont has recently found extraordinary success. This has been particularly true since Sanders's dramatic upset in 1981, when he won the Burlington mayoral race by ten votes. Since then, he has had considerable success in pursuing his program and evidenced great popularity in three subsequent elections. The Progressive Coalition has been able to find and field excellent candidates to the City Council (falling just short of a majority, but securing the ability to maintain a Sanders veto). Finally, Sanders made a credible showing in the governor’s race in 1986 — where he won 15 percent of the vote as an independent socialist, although he was outspent ten to one by his opponents.

The base which, in other parts of the US, had constituted itself as the left wing of the Democratic Party (labor, progressive Blacks and Latinos, feminists) does not really exist in Vermont, and so the strategy of left infiltration of the Democratic Party — articulated in this period by the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) — had not historically found many adherents on the left. Not until, that is, the dramatic effects of Jesse Jackson's 1984 presidential campaign began to have an impact on Vermont’s left. The Jackson campaign galvanized that sector of activists who had been devoting themselves to issue organizing (tenant, anti-nuke, anti-intervention, civil rights) but not electoral work during the long post-Vietnam War period. With a late start, no budget, no minority base, and the debilitating effects of the “Hymie” incident hitting just prior to the March 1984 Vermont primary, Jackson won only 8 percent of the vote at that early stage in the campaign.

However, a strategy of using Jackson's campaign to knit together and publicize a progressive issues program proved very dynamic. By the time the Democratic town caucuses were held in April, Jackson's share of the vote had risen to 14 percent; at the State Democratic Convention in June he captured 20 percent of Vermont's delegation to the National Convention. A swell of excitement about being able to defend a progressive program within the mainstream electoral arena also fueled the election of leftists to party posts. A publicly visible socialist, with no previous relationship to the Democratic Party, won the post of Democratic National Committeewoman at the State Convention. Rainbow activists were elected to posts in town, county and state Democratic committees.

The crafting of the state party platform was commandeered by the Rainbow, resulting in an outspoken — even radical — document. Many of the state's most seasoned issue leaders were drawn into this arena, incited by Jackson's audacious challenge to conservative Democratic policies. Despite Jackson's routing by center/reactionary national Democrats at the 1984 Democratic Convention, or perhaps because of his dignified and principled response, the forces that had comprised his Vermont campaign were eager to stay together.

The next stage of development began immediately without a period of consolidation or strategizing. Events overtook the moment as several leading progressive activists decided to run for state legislative office, publicly upholding their Rainbow identification while running as Democrats. Five out of seven Rainbow Democrats were elected to the state legislature. A long-time Central America activist with no previous electoral experience won the Democratic primary for Vermont's single congressional seat, and went on to run a dynamic and issue-oriented race against five-term incumbent Representative Jim Jeffords.

The election period was a time when progressives were bringing to bear their considerable expertise in grassroots organizing and issue development in a more mainstream setting than most had ever operated in before. What in other states are absolutely necessary skills for an election campaign (voter identification, phone polling, major fundraising events, expensive media campaigns) could more easily be glossed over in Vermont — at least the first time out — because local elections are still generally amateur events.

Consequently, the lack of experience in traditional electoral techniques did not set progressives back, at least at this juncture. There were fresh working alliances with Democratic Party stalwarts, which lent the progressives — who had long operated on the margins of political life — a sense of new opportunity. Party Democrats welcomed the energy and tenacity of the “newcomers,” and responded in a variety of ways to indicate their openness to the left forces. One telling example was the willingness of the State Compliance Committee (overseeing the rules for delegate selection to the Democratic National Convention) to defy the Democratic National Committee and reduce the threshold for delegate selection from 20 percent to 10 percent, the position advocated by the Jackson campaign. To all appearances, the Jackson campaign was the spark for reinvigoration of the state Democratic Party.

Inside/Outside the Democratic Party

The honeymoon between the Rainbow left and the Democratic Party was, however, short-lived. One of the Rainbow’s first considered acts in statewide electoral politics (after Jackson's elimination from the presidential race) was to decline to endorse the Democratic nominee for governor, Madeline Kunin, on the principled ground of not supporting “lesser of two evilism” politics. Kunin, though she was a woman and though she had been a liberal at the start of her political career, then strongly supported by feminists and labor, was not a progressive in the left-tilted context of Vermont in 1984. Rainbow leadership (including the Rainbow Co-Chair, who had been elected to the Democratic National Committee) often pointed publicly to this nonendorsement as evidence of their inside/outside relationship to the Democratic Party — a theme that would only become more pronounced as time went on.

The debate ignited by the spark of the Rainbow’s refusal to endorse Kunin has continued for the last four years. On the Rainbow side, the spectrum of positions has run from “We should become an independent political party” to “We should function as the left wing of the Democratic Party,” with the strength of the former position considerably outweighing that of the latter.

The Democrats' reaction was predictably ambivalent. Liberal Democrats at first believed that an active “progressive wing” would strengthen their influence within the party, but quickly saw that this particular group was not interested in being a tame left wing. When it became clear that Rainbow activists intended to maintain political independence, angry denunciations of the Rainbow’s refusal to endorse Kunin mounted. An unsuccessful effort was made to remove the errant Democratic National Committeewoman from her seat.

Conflicting tendencies within the party came to the fore, and those who did not want to lose the new activists argued for tolerance — the position which, more or less, ended up carrying the day. The Democratic State Party Chair, who led the purge efforts, was not supported by his own Executive Committee and resigned shortly thereafter.

The arguments in favor of not alienating the Rainbow forces drew their rationale from the recent political history of Burlington. The lesson that far-sighted Democrats drew in 1984 was that they should do anything they could to avoid creating a “Burlington situation” throughout Vermont.

Burlington: Progressives versus Democrats

Bernie Sanders's razor-thin victory in the 1981 mayoral race came over an old-line “machine” Democrat (insofar as a city of 35,000 in an all-Republican state can claim machine politics). The city seemed nearly uniformly excited that a boring, increasingly complacent era was being swept away by new winds. Sanders fought tough and exhausting battles to make the new city administration effective in creative and audacious ways. His popularity zoomed among progressives (who had initially taken a stand-off attitude toward his campaign), unions and poor people.

With the support of several talented progressives elected to the Burlington City Council (some as independents, some on a Progressive Coalition slate, and one as a Citizens Party candidate), as well as an extraordinarily talented cadre of progressives in city administration appointments, many policy initiatives were undertaken. The Sanders administration found ways to fight the private utilities, including imposing fees, challenging monopoly franchises, and redesigning rate structures to benefit residential customers and reassign the burden to commercial users. Sanders worked to greatly enlarge the available stock of moderate-income housing in the city through creative grant work, the development of a land trust, and restrictions on condominium conversion.

The administration sought to promote alternative — as well as more mainstream — economic development, to fight for and win important changes in local taxing authority to reduce reliance the regressive property tax, and to initiate innovative programs primarily affecting women and children. These last included the state's only municipally funded day care center and a shelter for battered women (both of which spun successfully off into independent enterprises), an after school program for the children of working parents, a Women's Council, a city ordinance requiring the employment of a set percentage of women on any construction work contracted by the city, and women's self-defense classes. Sanders's mundane, but equally impressive, exercises of public authority also won adherents — including house cleaning of dead wood in the government, a move to institute competitive bidding for public contracts, and an upgrading of street repair and public services in general.

More controversial was Sanders' unwavering commitment to having a “foreign policy,” one, not surprisingly, characterized by outspoken anti-imperialism and public activism. Burlington City Hall became host to every major demonstration, and the site of regular speaking engagements. The city divested itself early of South African investments and established an extremely important Sister City relationship with the Nicaraguan city of Puerto Cabezas, which has been the springboard for some of the most effective material aid campaigns in the entire state. Sanders used every opportunity to link conditions and issues within Burlington to the national and international economic context, and to challenge Reaganism and imperialism in its every manifestation. This tenacious refusal to allow any false isolation of “local” politics from global politics has been one of the most heated points of dispute among Sanders' critics — and one of his highlights for the left.

Overarching these specific policy initiatives has been a single accomplishment, probably unmatched anywhere in the US: Burlington has become a politicized town, with an uniquely informed and motivated electorate, with passionate contests waged for virtually every modest public post, and with debate proceeding on the true issues of political life: who has power and how are they using it. And this happened in the context of the only town in the country that has a three-party political system. For its extraordinary ability to take a fluke electoral win and turn it into the most powerful progressive political entity in the nation, the Progressive Coalition earned deep enmity in some quarters.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the most unyielding opponents of the Progressive Coalition in Burlington were the Democrats, who had been summarily knocked down to “third party” status and found themselves abandoned by their own most forward-thinking supporters. On the Board of Aldermen, where pitched battles were regularly fought out, Democrats consistently sought alliances with the Republicans rather than the Progressive Coalition. In part because of this antagonistic relationship (and in part because of Sanders's personal disgust for bourgeois parties and their hold on American politics), the Progressive Coalition came to embody an institutional anti-Democratic Party pole — expressed most dogmatically by Sanders himself.

When Jesse Jackson made his single Vermont campaign visit in 1984 and went to pay a call on Sanders in City Hall (having been incorrectly led to believe that he would find a warm welcome), Sanders gave him the cold shoulder. In like fashion, Sanders upbraided any members of his administration — and there were many — who worked on the Congressional campaign of Rainbow Democrat Anthony Pollina. (It should be noted that this very inflexibility on Sanders's part, exposed as it was in the popular campaigns of Jackson and Pollina, became the source of later estrangement for a number of his chief political aides, who argued that progressives should not engage in doctrinaire posturing during this period. Several of them have become staff members and organizers in progressive — not necessarily Rainbow — Democratic electoral campaigns.)

This atmosphere of hostility to the Democrats created a situation in which Rainbow leaders in Burlington, pursuing a strategy of working with the Democrats when appropriate, were held in suspicion by the Progressive Coalition. Several members of the State Legislature who had been elected as Rainbow Democrats were viewed with disdain (despite their willingness to support Sanders's agenda in the Legislature) until they publicly endorsed a Progressive Coalition candidate in an aldermanic run-off race against a Republican in 1986. In this episode, the Democratic candidate had been knocked out of the contest, and Democratic Party leaders, to avoid giving any aid at all to the Progressive Coalition, threw their support behind the right-wing (Citizens for America) Republican contender.

When the Rainbow legislators endorsed the Progressive Coalition candidate, city Democratic leaders freely threatened that they would never win another election in Burlington. They tried to make good on this threat in the 1986 legislative elections by writing in several old-line Democrats on the Republican line to challenge the Rainbow Democrat incumbents.

These Republican/Democrats were handily defeated, signaling a realignment process in Burlington the dimensions of which are broad and possibly enduring. Another and crucially indicative event in this realignment trend was the nomination of a conservative Democrat to go head-to-head with Sanders in his January 1987 bid for a fourth term as mayor, with agreement from the Republicans to stay out of the race. Burlington, after six years, was once again having a two-party election contest: the Progressives against the Republicrats. The Progressives won again; the fusion Republican/Democrat candidate was routed.

The Sanders Wild Card

It could be argued that, were it not for Bernie Sanders and his central position in any progressive electoral strategy for Vermont, the Rainbow Coalition could well have devolved into a left wing of the Democratic Party. Certainly the individual decisions taken by many Rainbow activists to run for legislative office in 1986 as Democrats rather than independents would have logically led to close functional relationships — the sharing of lists, resources, money and expertise. And even were this trend actively struggled against on the theoretical front by proponents of a third party within the Rainbow, the material realities of campaigning as a Democrat tend to move candidates towards the party's center.

This slide towards the comfortable middle was not an option for the Rainbow, because Sanders was, and is, a reality to be reckoned with by all of Vermont's progressives. And it was his long-nurtured desire to compete seriously in the governor's race that came to shape the Rainbow strategy in 1986 more than any other single factor. Beginning with the debate over whether he should run in 1986, advancing through the question of the Rainbow Coalition's relationship to his campaign, and continuing still through the post-electoral analysis and projected game plan for 1988, the features of Bernie Sanders’s own political style and strategy have dominated the discussion.

Sanders is a complicated player in a complicated game, yet his favorite summary statement for any political conundrum is “Look, it's really not all that complicated,” meaning, almost invariably, “We are acting out the class struggle, and any situation can be analyzed in that light.” That he has often been out of step with the times in his life-long quest to resist bourgeois cooptation, while at the same time competing for public power, is demonstrable (although some of his left critics — notably the grouping of Greens coalesced around anarchist philosopher Murray Bookchin — argue that he has sold out the working class on various issues). That he is a difficult personality is universally agreed — driven, demanding, and unlikely to take the time to build trust or consensus with allies.

But it remains that the most important thing to say about Bernie Sanders is that he is one of the only major officeholders in the United States in this decade to fight for a radical, class-based political program as a socialist. If he has not built a powerful independent party, if he has not advanced socialist goals sufficiently through his municipal government, if he has alienated key supporters through personal arrogance and failed to create alliances that could have been made (the categories of criticism most frequently leveled at him from the left), these are the difficult features of his style of leadership. And while the problems that flow from his style have been burdensome in Burlington politics, they surged to the fore when Sanders began discussing a race for governor.

The Progressive Coalition members of the Burlington Board of Aldermen and the city administration, as well as street-level activists throughout Burlington, were nearly unanimous in opposing a Sanders campaign for governor in 1986. Their reasons covered a range of opinion: many did not want to risk losing the gains made in Burlington; others feared that Sanders lacked a sufficient base and contacts outside Burlington and that he would suffer ignominious defeat; some argued that a race against an incumbent woman Democrat was an illogical splitting of the progressive vote.

But another, more uniform sentiment also bound the Progressive Coalition forces in their view of Sanders's plan. Nearly everyone agreed that Sanders would not seek input from his supporters, and that he would not respond to ideas that differed from his own judgment. It has become a given among Progressive Coalition activists that Sanders makes up his own mind — a feature of his leadership that is sometimes brilliant (when a seemingly cockeyed intuition proves to be just right) but is almost always deeply disturbing to progressives who value democratic processes. As, one by one, the stalwarts of previous mayoral campaigns indicated their unwillingness to be drawn into what they considered an ill-conceived campaign, Sanders turned deliberately to the Rainbow Coalition, which was organized statewide.

The Rainbow and the Sanders Campaign

The tendencies within the Rainbow that had kept it floating for several years both inside and outside the Democratic Party were set at furious odds against one another when the question of supporting Sanders for governor came up. It was not a question of people actually coming to Governor Kunin's defense; far from it. Kunin had managed, in her two years in office, to disappoint most progressives in all sectors — labor, social services, teachers and environmentalists — with an infuriatingly cautious, often neo-liberal approach to public policy. Rather, it was the prospect of having to defy both the Democratic Party and the hegemony of the two-party system by opposing Kunin, that seemed to create panic.

These arguments came wrapped in pragmatism (“Sanders can’t win anyway, and we will burn our bridges to Kunin”) or veered off into irrelevance (“Why doesn’t he run for Congress” against — it should be noted — the Republican incumbent who had been unbeatable for six terms, and who even the Democrats did not challenge in 1986). Nor were people explicitly defending the Democratic Party, but rather the access to the party that progressives had secured over the previous three years. Those who argued that support for Sanders would cause a definitive break with the party generally took themselves out of active Rainbow participation as the campaign proceeded. This, if it were to be labeled, would have to be called the “right” opposition position.

The “left” opposition within the Rainbow was qualitatively quite different. Here the concern was focused on Sanders and his own history — one that is characterized by a clear lack of emphasis on organization building and democratic processes. For those Vermont progressives with a commitment to left independent politics, there is a strong appetite for bottom-up, grassroots democracy. Sanders is widely understood to be — by his own choice and description — outside this trend, leaving him oddly isolated from his best natural base of progressive issue activists. But at the same time and almost in spite of themselves, it was these same activists who were most compelled by his program, his powerful rhetoric and his unique ability to reach poor and working-class people with the zeal of a class fighter.

This group — representing, ultimately, the dominant position within the Rainbow — came to believe, perhaps with some degree of wishful thinking, that Sanders's own anti-organization stance could be overcome by the Rainbow’s plan for base-building. The Sanders campaign, which the Rainbow eventually supported both formally and through the transplanting of its central administrative staff to the campaign, was to be run along a grass-roots organizing model. It hoped that the same sort of disenfranchised constituencies that came into the Jackson campaign and ended up mingling with progressive organizers would also be galvanized by Sanders and stick around to constitute a broad community base for ongoing progressive activity.

Initial chaos mingled with euphoria characterized the beginning of the Sanders campaign. A faint air of conspiracy attended those who, early on, called the office or asked for campaign buttons. Some Democratic officeholders, angry at Kunin and glad to have a way to put her on notice, made some guarded overtures to Sanders. People stopped at campaign events to say that they had never voted in their lives, but that they would vote for Bernie. But rather quickly, these isolated incidents gave way to the harsh realities of an independent challenge.

There were three natural constituencies that progressives could expect to carry the weight of such an ambitious campaign: the unequivocally independent left (whose highly experienced forces were concentrated in Burlington); the inside/outside Rainbow cadre (centered in Montpelier); and the natural — but often unformed — leaders among poor and working-class networks. If all these elements had enthusiastically and harmoniously come together in the campaign, perhaps the most formidable obstacles (fundraising, media, and political organization) could have been overcome. As it was, the earliest — and perhaps most debilitating — reality the campaign had to face was the withholding of energies by all of these groups.

Attempts to draw some Progressive Coalition strategists, fundraisers and organizers into the early parts of the campaign were largely, though not entirely, unsuccessful. The pervasive attitude of members of the Sanders administration in Burlington and Progressive Coalition leaders was guarded. People felt, justifiably, that since they had not advocated a gubernatorial campaign, they could not be expected to drop everything to work on it once Bernie made his own decision. A consensus instead emerged that the city administration, and the Progressive Coalition as a political organization, needed to work on surviving Sanders's departure (even if only for the duration of a campaign).

The questions of maintaining a vigorous city government, of developing a new generation of popular and effective leaders, and of maturing past the stage of being a Sanders phenomenon, were very much in people’s minds. The result of these attitudes was a tremendous loss of needed talent and experience from the early campaign work. Since this group included the closest of Sanders's colleagues, friends, and supporters from his mayoral tenure, he also suffered from a personal isolation in this endeavor that took its own toll. It is, however, difficult to consider this problem of support from the Burlington forces as broadly instructive for the left elsewhere in the country. For one thing, it was Sanders's style of highly individual decision making that created the atmosphere of reserve among his supporters — and not any disapproval among them for his ultimate goal of higher political office. In fact, it was the wide support for him as a public leader that eventually brought many of these forces into the campaign towards its conclusion.

Equally problematic was the response or, rather, lack of it, from left/progressive activists outside Burlington. From the start a nucleus of experienced organizers, located primarily within the Rainbow Coalition, committed themselves to the Sanders campaign as their central task for a six-month period. This group was characterized both by its years of involvement in many issue constituencies in the state, and also by its limited investment in the Democratic Party. It is probably fair to describe the view of the Democratic Party held by this group as tactical, not strategic. (One Rainbow leader argued this way: we need to view the Democratic Party as a community organizing target, and not as the community organization itself.)

Central to any success that this group could achieve in supporting Sanders would be the response from other issue leaders. Since Sanders pulled no punches on his positions on the issues (calling for the shutdown of Vermont's only nuclear power plant, progressive tax reform, a major reemphasis on social services, aggressive targeting of corporate polluters, support for the struggling family farm economy, etc.), the campaign generally believed that leaders in these issue areas would energetically rally behind his candidacy. Further, there was little concern that loyalty to the Democratic Party would be a problem because neither Kunin nor the Democratic Party ın the state had actively courted or aided these issue leaders in any consistent way. This assessment proved to be profoundly naïve, however. As the campaign unfolded, the struggle with the liberal/progressive center forces more and more dominated strategy.

The unexpected dynamic that displayed itself from the outset and that was not resolved until perhaps the last two weeks of the campaign (and only then because of a mini-scandal that erupted in the Kunin administration), was the state of frozen ambivalence in which many progressives found themselves. People who had no trouble engaging in civil disobedience to protest the contra war in Nicaragua, who organized in their churches for nuclear freeze resolutions, who lobbied their legislators for divestment — in short, people who saw their lives as dedicated to political activism — were entirely unwilling to face the implications of an independent electoral challenge.

Rather than fight for a bourgeois politician (although, to be sure, there were those who offered a defense of Kunin because she was a woman and “not bad” on many issues), the majority simply opted to sit out this historic race. People did not even want to debate the issue but rather consigned it to some highly personal, almost moral, sphere and kept their thoughts private. Energies flowed instead toward the much cleaner race between incumbent Democratic Senator Patrick Leahy and his rich businessman opponent, Republican Dick Snelling. Leahy had a wealth of volunteers and a campaign infrastructure that was extraordinary. His staff included many leaders of progressive issue groups (such as one of Sanders's most talented former administration members). Money poured into the Leahy campaign, with the surplus so substantial that Leahy was able to donate money to the struggling Kunin campaign. This was the way for many to displace their disquiet over the Sanders-Kunin choice by simply avoiding it.

Without this stratum of support — its organizing expertise, its contacts and ability to influence networks, and, most definitely, its ability to raise money — there was hardly a realistic possibility of organizing the third natural constituent base. Without knowledgeable organizers to build the structure, those Sanders supporters with no ambivalence towards the campaign (poor and working-class Vermonters) could not be effectively moved.

The requirements of voter registration, voter identification and voter mobilization among the disenfranchised constituencies are, minimally, enough money and enough volunteers to beat the bushes in the trailer parks, backwoods, and tenements to produce a noticeable vote. The Sanders campaign was not able to muster these resources. When Sanders, facing these severe limitations and unwilling to withdraw from the campaign, decided to forge ahead, the entire staff was laid off and reorganized with volunteers. The headquarters was relocated from Montpelier to Burlington and the strategy entirely redrafted to reflect the limited financial and human resources.

Fundraising for the Sanders campaign was, not surprisingly, extremely difficult. Institutional sources that historically had supported the progressive wing of the Democratic Party were generally entirely hostile to a third-party candidate. Even those labor unions whose national leadership was linked to Jesse Jackson and the Rainbow Coalition (such as the International Association of Machinists and its social democratic president William Winpisinger) would not break ranks with a Democratic incumbent. Sanders won support from only a few union locals, including the small but outspoken United Electrical Workers Council in Vermont. This lack of union support was particularly galling in light of Sanders's outstanding track record on labor and class-based issues.

Women’s organizations were keenly antagonistic, despite Sanders's far more aggressive support for the state ERA referendum (which shared the November ballot), and his generally stronger record on feminist issues than Kunin. The state's environmental groups, long a conduit of significant campaign funds from national sources, snubbed Sanders entirely. In fact, so thorough was the financial blacklisting by Vermont and Washington-based liberal organizations that even a nonpartisan voter registration project, organized by an assortment of Vermont groups including the Rainbow Coalition of Vermont (RCV) and entirely separate from the Sanders campaign, was boycotted by half a dozen foundations.

In all quarters the rationale was the same: “There is a Democrat in office. Let's not risk splitting the vote and electing a Republican.” Decades of “two partyism” have left deep instincts of habit and fear, so that even progressive donors who fund left-issue organizations of every sort shrink from the terror of “risking Republicanism.” This is an ironic feature of our political landscape that will continue to hobble serious third party efforts, while leaving intact the issue organizations from which these parties often spring.

Sanders turned to a small core of very committed supporters in Burlington to continue his campaign — relying more on public appearances, free media and debates (all arenas in which he excels and could use effectively to promote a superb platform) than on grass-roots organizing and voter registration. Although the problem of money was never overcome, Sanders maintained a broad and serious presence in the governor's race. Sanders was not dismissed as marginal, and, in fact, exerted leftward pressure around issues that many had hoped for — moving both the Democrat and Republican candidates along in areas of taxes, utilities and nuclear power. His campaign did not ignite, but neither was it ignored, and he received a credible 15 percent of the vote in November, enough to rob Kunin of her required 50 percent majority by 2 percentage points and bring the election to the Legislature for formal ratification.

Rainbow/Democratic Legislative Campaigns

In addition to Sanders’s independent campaign for governor, 1986 saw a raft of Rainbow/Democratic legislative campaigns in Vermont. The issues Sanders ran on, and even the principle of his independent candidacy, were central to many of the Rainbow/Democratic legislative campaigns. This is not surprising since the RCV had determined to support (through recruitment, fundraising, and technical campaign work) candidates — both Democrat and independent — based on their demonstrated commitment to the RCV platform. Sanders met this criterion, as did about a dozen legislative candidates (including half a dozen from the RCV Steering Committee, of whom half were elected).

The inside/outside strategy flowered in all its complexity during a protracted period when these legislative candidates, running as Democrats with clear RCW identification, were debating whether to support Sanders publicly. The question was never whether to support Kunin, but whether to remain studiously neutral on the question. The price of endorsing Sanders, it was felt, would be to risk sabotage from the party and/or the media for betraying the “top of the ticket.” As the campaigns unfolded, individual choices were made by candidates — with those who were most deeply committed to the RCW openly endorsing Sanders and often, consequently, fighting brushfires on both the right and the left. Andrew Christiansen, the co-chair of the RCW and a native Vermonter who still lives on his parents’ dairy farm, was attacked in a newspaper display ad taken out by a Republican town official one day before the election: “Andrew Christiansen is running for State Representative from East Montpelier. He belongs to the Rainbow Coalition of Vermont and he supports Bernie Sanders for Governor.” Christiansen was elected. On the other hand, Liz Blum, a RCW leader and long-time progressive activist and Rainbow/Democratic candidate for State Senate, was actively undermined by liberal Democrats in her home county for publicly campaigning with Sanders. She, unfortunately, lost.

While the incontrovertible evidence is that the Vermont Democratic Party as a whole has moved leftward while achieving majority status, and specifically that its elected officeholders in the State House and Senate are increasingly liberal, the role of the RCV within it was constricted by its alignment with Sanders. As long as the RCV played a gadfly role, as long as it proclaimed political independence without actualizing it, to that degree liberal elements within the party could identify with its “loyal opposition” role. However, the Sanders campaign — and the RCW's public support — polarized those elements into a dramatically anti-third-party stance.

Repeatedly, these party liberals advocated Sanders's entry into a Democratic primary. This, they argued, would make it possible for them to support him and his progressive program. Otherwise, he would need to be punished for not playing by the rules, and suffer the consequences of losing liberal support and financing. (Since Sanders himself disdained this liberal element and did not look to them for support, he was unmoved by their arguments and undaunted by their rejection.) And, if anything, this rupture between the RCV and the Democratic Party did not surprise the leadership: its goal had been to move the party to the left on issues, while simultaneously challenging the party internally and externally by support of third-party candidates. The aim, at this stage, was not to initiate an independent political party, but to draw constituents to a specific independent candidate as an achievable step in the direction of building a third party. Although the number of party Democrats who, supported Sanders was, apparently, quite small, the credibility and seriousness of an independent candidate became a matter of record, not theory. This, by itself, contributed to the forward movement of independent electoral politics and the erosion of two-party hegemony in a tangible way.

The 1988 Races

In 1988 Vermont's only US House seat came open after twelve years of incumbency by Republican Jim Jeffords. Sanders entered the race as an independent. He immediately drew more support than he had two years earlier in his run for governor, partly because the seat was open (with no incumbent Democrat to dump), as well as because of some general sense that Sanders's powerful identification with foreign and national policy concerns coincided more clearly with a national office. This open congressional seat — more and more a rarity in US politics these days — also had an intoxicating effect on the Democrats, and a crowded primary season ensued. The effects of the party being pulled leftward were evident in this unusual primary, which pitted two of the party's leading liberals against a prominent labor Democrat of increasingly liberal tendencies and a progressive Black female university professor. Progressive activists around the state, as in the 1986 campaign, were somewhat divided among these choices — although much more energy coalesced around Sanders from the start.

The RCV, already in high gear for Jesse Jackson's presidential campaign, was approached by Sanders and all four Democratic candidates for an endorsement. A decision to endorse Sanders again alienated certain elements within the Rainbow who had favored one of the more convincing liberal Democrats, President Pro Tem of the Vermont Senate Peter Welch. But when Welch was narrowly defeated in the primary by more moderate House Majority Leader Paul Poirier, labor's choice, the progressive consensus firmly reestablished itself around Sanders.

In this campaign, Sanders was both a source and beneficiary of a tremendously strong campaign for Jesse Jackson in the state. The maturity and organizational capacity developed by the RCV in the four years since Jackson's last campaign paid off with an energetic and broad effort — this in spite of the fact that virtually every Democratic office-holder came out early for Dukakis, and that Vermont's next-door-neighbor relation to Massachusetts was counted on to deliver the state for him.

Compared with his hands-off approach to Jackson in 1984, this time around Sanders was a visible and enthusiastic supporter and appeared with him during one of Jackson's two campaign visits to Vermont. When Jackson won the presidential primary in May 1988, it gave an enormous psychological boost to progressives and was particularly felt as it rippled back through Sanders's campaign. A dynamic of reinforcing excitement was palpable between the two campaigns, causing Democratic regulars to comment with increasing frequency in the press that the technical organizing skills that progressives were wielding didn’t necessarily reflect the political views of Vermonters.

The authentic political views of a population are always hard to interpret — particularly when the indicators are electoral results. The facts of the 1988 elections in Vermont were these: Jesse Jackson won the Democratic presidential primary and George Bush carried the state in the general election. A Republican won the race for US Congress, but Bernie Sanders lost it by a mere 3 percentage points. Both the Jackson and Sanders victories (it cannot be called less when an independent socialist comes that close to being elected to the US Congress) must reflect not only good effort on the part of progressives, but the tapping of some well of populism that is, minimally, neither racist nor reactionary (as some tendencies of American populism have been).

The Succession in Burlington

In March 1989, another crucial test was waiting for Vermont progressives. Burlington's Progressive Coalition activists, hardly recovered from the rigors of the November election, had to face a race for mayor, as Sanders definitively declined to run for a fifth term. Sanders's director of economic development for the last six years, a native Vermonter of working-class and regular Democratic background, Peter Clavelle, was nominated by the Progressive Coalition. Opponents of all stripes were waiting for this moment of vulnerability. The Democrats and Republicans (perhaps the name “Conservative Coalition” would be apt here) ran a fusion candidate who they hoped would break the progressive winning streak in the city. From another direction came a challenge by the Burlington Greens, who ran attorney and long-time left activist Sandra Baird for mayor and two other Greens for City Council seats. This move didn’t herald, but rather capped, a long and bitter split between the Greens and the Progressive Coalition — an antipathy that periodically flamed over issues of development and the environment, the two areas on which the Greens most consistently attacked Sanders and his administration. But the regular bouts of verbal bashing and occasional hostile campaigns (as during a still-controversial episode in which the Sanders administration attempted to pass a public referendum for development of Burlington’s waterfront, while the Greens successfully organized against it, claiming that it represented gentrification), accelerated precipitously during the mayoral race into ideological warfare.

Until this moment, the Greens’ public statements (accurately reflecting the anarchist perspective of their leader Murray Bookchin), had showed distain for an electoral strategy and instead had emphasized building a broad-based grassroots movement that could sweep before it massive structural and economic change. Running for office was a distinct change of strategy for the Burlington Greens, and left Progressive Coalition leaders feeling, and charging, that the Green electoral challenges were not serious but merely spiteful. In Progressive Coalition circles, it was common to hear the analysis that the Greens had been unwilling to mount a campaign against the wildly popular Sanders, and that they were running at this moment to exploit the perceived weakness of an open mayoral seat.

Other standard charges emerged on both sides: the Progressive Coalition argued that this split of votes would cost the city its progressive administration; the Greens responded that the Progressive Coalition was in fact no different from the Democrats and Republicans, so that such an outcome wouldn’t matter. Publicly, Clavelle ran on the strong record of accomplishment during Sanders’s tenure, and publicly, Baird said that any economic prosperity in this period in Burlington had accrued to the affluent, while class stratification and homelessness grew. Privately, the Progressive Coalition activists were furious over the refusal of Greens to work with them and even angrier that the Greens seemed willing to turn the mayoral race into a PC–Green fight and leave the Democrat/Republican entirely unchallenged in public statements and debates.

Both the bourgeois and the left press of course found this a compelling story. The possibility that one of the most important independent-progressive city administrations in the country might be seriously threatened both alerted and activated progressives beyond Burlington. Drawing on the base from the Rainbow Coalition and the Jackson campaign, Clavelle was able to raise money and volunteers in abundance, while the skill and experience of Progressive Coalition workers, who had mounting campaigns for eight years, shaped an efficient effort.

The outcome was not really close: Clavelle won handily, and Baird drew only about 3 percent of the vote. The two Green candidates for City Council fared better (winning between 15 and 20 percent of the vote in the races), but neither was elected. As a footnote, Progressive Coalition City Council member Erhard Mahnke was unexpectedly elected President of the Council, which still lacked a Progressive Coalition majority. The succession from Sanders to another PC mayor was profoundly reassuring to progressives in Burlington and elsewhere, and Clavelle's first six months in office have been marked by a consistency of progressive character.

Next...

The left in Vermont has just had an anniversary party: on 13 and 14 June 1989, five hundred people attended the Second Vermont Solidarity Conference, the first having coincided with both Reagan's and Sanders's elections in 1981. Sanders, Clavelle and other PC activists were on hand to debate the Greens, but this was just one theme against a background of evaluation and planning among the hundreds of activists who attended. Other discussions focused on the reaction to recent changes in the National Rainbow Coalition made by Jesse Jackson, and the implications of those changes for the Vermont Rainbow, the linking of environmental work (ever more imperative). with other progressive activism, and the tremendous ferment in the communist world. An extraordinary decade of activity in Vermont was reviewed, and the movement continues.