Dorothy Thompson: The Personal and the Political

In this 1993 interview with Sheila Rowbotham, Dorothy Thompson reflects on her life as a historian and as a socialist.

Published by Verso in 2011, Lives on the Left: A Group Portrait — edited by Francis Mulhern — collects sixteen extended, critical interviews with left intellectuals undertaken by members of the New Left Review editorial board. "In the late 1960s," Mulhern writes, "New Left Review began to develop the interview form as an integral element of its publishing repertoire..."

The great advantages of the interview are its manoeuvrability and range. Beginning, usually, in a conversation and resulting in a printed representation of that, its production process is more complex than this suggests, combining the greater spontaneity and pace of speech with the greater scope and control available to both parties in written revision and supplementation, where in fact much of the work of composition may occur. A singular form only in the minimal sense in which the novel can be said to be one, the interview accommodates a whole array of spoken and written varieties at both poles of the exchange (exposition and narrative, and elicitation, but also argumentative rallies, interjections, anecdotes, asides) and licenses elliptical transitions from one topic to another — jump-cutting — in relative freedom from the constraints of the standard article form. At other times, it may serve the purposes of what might have been an article, creating a monologic argument or narrative with a facilitating second voice, in effect. Some of the interviews reprinted here move at this end of the range, offering extended and methodical historical treatments of their material. But even in those cases, the differences are palpable. For the interview as conceived of here is among other things a kind of portraiture, or rather self-portraiture — and a mode in which, then, however discreetly, thought becomes thinking, something of its character as a process is reanimated, as concepts find their forms and effects in the grain of biographical sequences and historical construction is re-inflected in the lived interpretations of memoir.

Included in the volume is Sheila Rowbotham's 1993 interview with Dorothy Thompson, reprinted below.

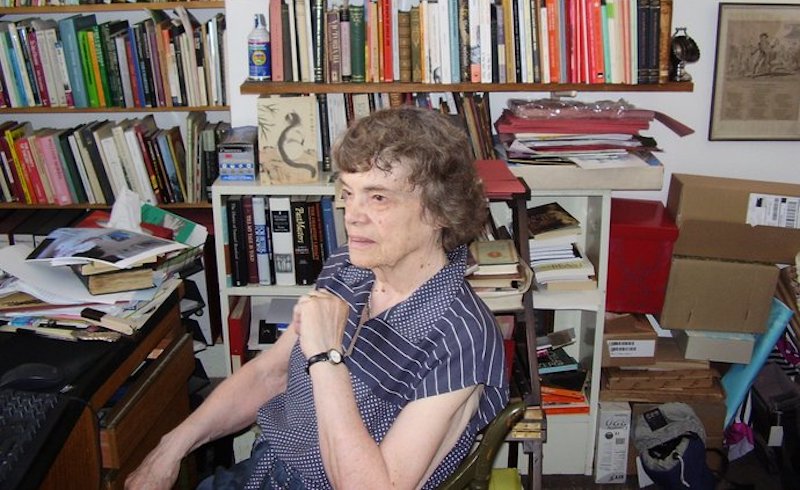

Dorothy Thompson was born Dorothy Towers in London in 1923. After graduating in History from the University of Cambridge, she worked in adult education in the North of England and remained active in the Communist Party, which she had joined at the end of the 1930s. She resigned from the party after the Soviet invasion of Hungary. From 1968 to 1988 she taught in the School of History in the University of Birmingham, where she wrote a series of highly regarded books about Chartism and other topics in nineteenth-century British history — among them, Early Chartists (1971), Chartism in Wales and Ireland (1987), Outsiders: Class, Gender and Nation (1993) and Queen Victoria: Gender and Power (2001). Her edited volume Over Our Dead Bodies: Women Against the Bomb (1983) testified to her engagement with post-war peace movements. She was married to the historian Edward Thompson (1923–93). This interview was given to Sheila Rowbotham in 1993.

Your book Outsiders suggests a general feature of your work — an awareness of class as a general feature of society but also of the cultural nuances which bind or separate people into or between classes. Was there something in your family background which encouraged this approach?

I suppose anyone growing up in England starts asking questions about class almost as soon as they can speak and I suppose the milieu that I grew up in — a South London theatrical and craft background — cut across traditional working-class areas. Nobody in my family ever worked for anyone else, except in the short term, but on the other hand nobody ever employed more than a few people. We were the artisanal layer, I suppose, and we had a very strong tradition of independence and self-education. My paternal grandfather, a shoemaker by trade, worked part time on the music halls. Two of my uncles were full-time dance band musicians. Others were tumblers and that kind of thing. My father and mother were both professional musicians, although my father set up a business running music shops and my mother mostly spent her life teaching, but also did some performing.

You lived in south London for most of your childhood?

Yes, I’m quite proud of being a third-generation Londoner. We are rather a rare species; people usually move out of London by the time they earn enough money to be able to afford it. I had a lot of relatives in places like Forest Gate, Woolwich, and Greenwich. I was born in Greenwich and so I knew a lot of London families, mainly connected with the river or with the theatre — at the lower levels, not the top theatre people. And there was also a branch of the family who were descended from Huguenot weavers in Bethnal Green. They still had their own memories of the weaving community.

What is your first memory of a political event?

It’s difficult to date this kind of thing but I do remember the General Strike in 1926. I remember my father bringing some people home — he had a little motorcar — and these people were stranded because of the strike, we were told. My brother sent the contents of his money box to the miners. I remember an item in the newspaper, the Daily Herald, which said that Tommy Towers had sent the contents of his money box to the miners. So I can date that clearly in 1926. I don’t know how far it influenced me but certainly it’s an early memory.

Can you say what influenced you politically?

My earliest childhood memories are of a time when we’d moved out of central London to Keston, in northern Kent, and we lived in a village mainly occupied by labourers’ families. I remember the little girl who was our daily maid telling me very indignantly that the people next door had taken a lift from my father to the polling station and he was only offering to take Labour voters. But she knew they were Tories because they took the Daily Mail. So I was aware of the difference between the Daily Mail and Daily Herald by the time I was about five. That’s not really politics but it’s certainly the rhetoric of politics.

You got involved in politics when you were quite young?

Yes. The family always supported Labour and I decided I was a communist quite early on. I joined something called the Labour Monthly Discussion Group when I was about fourteen, then the Young Communist League, and then the Communist Party. There was very much a political atmosphere in my family although no one ever belonged to anything. I was the first one I think to do that. But they had always read radical journals and newspapers.

When did your interest in history begin?

I had to make my choices about subjects at university just at the beginning of the war and my first choice would have been languages, linguistics or European languages, but that was obviously out because of the war — one couldn’t travel, I couldn’t go and study abroad. We had a very good teacher at school who got us very excited by history. It was when I was about sixteen or seventeen that I realized that history was a problem-solving discipline and not just an information-absorbing one. I got interested in history because it linked up with my interest in politics, and with family memories. For instance I was always enormously puzzled that one branch of the family had actually left their native country, left a comfortable living to come and live in the East End of London, simply because their version of Christianity was different from the dominant one. This seemed to be a major historical problem of considerable interest, because in my generation nobody in England seemed to feel that strongly about religion. To have given up everything for a sectarian difference seemed remarkable. This led on to political questions — why one group of people differ so profoundly when in fact they’re on the same side in a sense. The question of political theory, political thought, political analysis was something that I got very interested in as a teenager.

When did you go to university?

In 1942. Edward had been there for a year by the time I went and had already gone off into the army. I didn’t meet him till we both came back in 1945. By 1942 the political situation was very tense: the invasion of the Soviet Union, the need to open a second front. The campaign to persuade the British authorities to invade Europe occupied an enormous amount of people’s time on the Left. There were huge demonstrations in Trafalgar Square. I remember nothing of that size until the CND demonstrations. I went up to Cambridge and the second front came during my first year as a student so that the war and the politics of the war, the question of the Soviet alliance, all these things came together in the student politics of that time. We had a huge socialist club of a thousand members. Even in Bromley, in Kent, where I lived at this time, we had a YCL of nearly a hundred. I shouldn’t think they’d ever had more than about four or five before — or since. This was a time when — with the Soviet Alliance — there was a tremendous interest in left-wing and Communist politics.

Did any of your tutors at Cambridge have any effect on you?

Yes. The person who interviewed me for Girton College, subsequently my personal tutor, was Helen Cam, who was a great medievalist but also a very staunch Labour Party supporter. She couldn’t understand why the Labour Party wouldn’t accept me as an officer of their club — she wanted me to be the secretary of the University Labour Party. I pointed out that I was a member of the Communist Party and she didn’t see why that should be any objection. She was naive perhaps but very strongly socialist in her outlook. She was also a wonderful historian. She was a marvellous person to work with. She did have a lot of influence on me although in fact I didn’t study medieval history, I moved into the modern period. There was another tutor, Jean McCloughlan, who later became headmistress of a school in Scotland, who was very lively and interested in European revolutionary politics. I think the atmosphere at that time at Cambridge made it easy to be a radical and a historian.

This emphasis on the importance of mass political involvement is something that’s been important in your life. Do you think this is because when you first became interested in politics it was a time when there was a genuine connection of left-wingers to society on a wide scale?

I think this question of involvement in politics is a very interesting one. I always believed, until really quite recently, probably till about twenty years ago, that in an ideal society everybody would take part in politics, that it was natural for people to wish to have some control over their lives and that the best way of achieving this was by political structures and political activity in the broadest sense — through tenants’ committees, students’ committees, workers’ committees and so forth. It always seemed to me that this was what most people, if they had the time and the freedom and the education, would want to do. Only fairly recently did I discover that most people want a quiet life and that the dedicated committee person is the exception rather than the rule. I think this is one of the things I learnt by being involved in politics. As long as you are involved you think it is really the most important human activity, you think you really are changing the world and affecting history. But you have to be able to stand back a bit and realize that most people don’t see it in that way. One of the biggest shocks I ever had in Cambridge was when I discovered that people in the college lumped me together with the Conservative secretary, because we were both interested in politics. I thought we were at the absolute opposite ends of world experience, but in fact to the rest of the students the politicos, left and right, were much of a muchness.

Even during the Second World War?

Even during the war, yes. Obviously we took up different positions but nevertheless the fact that we both went to Union debates and attended political meetings put us in a minority. I see this now but in those days I was staggered when I found that people saw us as alike.

Do you think that even in periods of heightened mass involvement in politics it can only be at best a large minority that takes part?

It depends what you mean by involvement. In terms of actually going out on the streets, attending demonstrations, signing petitions, yes. But there have been periods when I’ve been absolutely amazed at the way totally non- political people have responded. In the early days of the peace movement, for example, my mother was a teacher in a rather posh private school. The headmistress asked her what she thought of those people who had broken in and sat down in a defence establishment, the first Committee of 100 action [an offshoot of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, founded in 1961 and committed to the tactics of non-violent civil disobedience.] My mother said she thought what they were doing was very necessary and that it was about time something like this was done. The headmistress replied, "So do I, so do I." My mother discovered that many of her non-political friends were supportive. I think that there are times when one can underestimate the amount of quiet and passive support for specific political campaigns. But as far as participation goes, it will always be a minority, I think.

Even in the days before we had universal suffrage, would you say that this was the case? For example in the periods about which you have written. Didn’t the big Chartist movements at least reflect a widespread mood and aspiration, even amongst those who never went on a demonstration?

Some historians would disagree with that. It’s a question that is almost impossible to measure. But if perhaps 80 per cent of the population vote in parliamentary elections, I think you can say that 80 per cent of the population would have taken one view or another about the vote, the men anyway. So many contemporaries say that this was the general opinion among working men, that the Charter was something they wanted, that I think it is so. But when you get a situation where half the population don’t vote, then it does suggest widespread alienation from politics.

When you and Edward came to Yorkshire, what was the effect of the people that you met in labour politics, women and men, on how you saw socialism?

One of the things about being in the Communist Party, and it was probably true at certain times about the Labour Party as well, is that it supplied a ready-made network of contacts and friends. I think the present generation of young people is unfortunate because such opportunities have declined. I don’t mean that they ought to join the Communist Party or whatever, but wherever you moved in those days you moved into a ready-made social set, so to speak: you went to a strange place, you got in touch with the Communist Party, and you had a circle of comrades. If you went abroad in the army to India, or American soldiers came over to Britain, to Cambridge, the Communists got in touch with each other. You were accepted, you were invited into their homes. This was certainly true when we went to Yorkshire. We soon got to know a group of very lively, very intelligent, very interesting people, through the Communist Party, as well as through our work with the adult education movement, which also had a structure there ready for us. By this time we were earning our livings, we were of an age when we were no longer students, we were no longer junior members of middle-class households, we were setting up our own household, having our own children. We met people on equal terms and one of the things that we discovered, I suppose everyone discovers, is how very ordinary students are; that a lot of the people we met who were engineers or nurses or factory workers knew a lot more than we did. This is perhaps brought home particularly when you go into adult education. You’re teaching but in many more ways you’re learning all the time. In Yorkshire we met people much more politically experienced and politically sophisticated than we were; certainly people with whom an exchange of views and experience was enormously enriching and valuable.

You once said that Simone de Beauvoir’s vision of emancipation missed out the really important thing, which was how you both have children and maintain your independence. That period in Yorkshire, both because of the women that you met and the fact that you were having your own children, must have affected how you saw the position of women.

Yes, it did. I was brought up by feminists — in my own family the women were certainly as talented and as influential as the men. Women taught me at school, an all-girls school and I went to an all-women college. These were brilliant women, scholars who could take their place in the world of scholarship with any men around. They very much wanted us, whom they saw as able girls, to go ahead and make our names in the profession. But because of prevailing social arrangements none of them had children. Most didn’t have husbands, and our generation of young female scholars, young female graduates, realized we had to make a choice — that we couldn’t, as we saw it, have a husband and family and home, if we wished to have a career. In those days, for instance, it would be very difficult to envisage a situation in which a husband and wife each had a job and he got the chance of promotion or a better job and they would not automatically go to where his better job was. Even the most enlightened and liberated women would think like this. Certainly by the time you started to have children there was no question of your having a totally independent career, because looking after the children was too demanding. So that many of my generation, the girls I was at school with particularly, didn’t go on to further education; they chose a husband and family and home-making and all that goes with it. It wasn’t all just drudgery, it was also having a home where friends and family could meet, and entertaining and amateur dramatics, and taking part in church and political activities. All these things went with having only one wage-earner in the family, and there were very few families that had two wage-earners to begin with, while the children were small. I carried on with my independent research and part-time work more than most people of my generation, but even so I wouldn’t have considered a full-time job until Edward gave up full-time work or until the children were old enough not to need support at home. So that the Beauvoir situation of two independent intellectuals having independent households and unlimited affairs was just not open to anyone who chose the option of children and home and family.

There’s a very strong awareness in your historical writing of the understandings that come from women’s activities in the home. While you are clear that these should not be imposed as a destiny, you also emphasize the positive potential of domestic experience, something that needs to be affirmed and brought into society.

A lot of the women in Yorkshire, in fact most of the married women I knew, did work. They went to work in factories and they hated it. They wanted the right not to have to work when their children were little. They didn’t see it as very liberating, that they had to make everyone’s breakfast, park the children with Granny and rush off and work eight hours in a factory where they’d get their heels trodden on and their bottoms smacked. Of course, there were things they liked. If they gave up working when their children were small, when they were bigger they often went back on the evening shift — for which they earned very little, but they missed the company in the factories. There are a whole number of tensions and contradictions: you may hate the work, but you like the company, you like the regularity, you like a bit of money of your own even if it’s not a big wage. The two-wage family was the norm in the Yorkshire textile districts when we were there, and you didn’t see this as an enormously liberating thing, although you did see these women as having a certain independence and strength and liveliness that the women in the South who were just coffee-morning and afternoon-tea sort of people didn’t have.

Your writing on women and Chartism shows that women cannot be conceived of as one group, as if all women share essentially the same experiences. Do you see this as still politically significant?

Yes. Some feminist writers — I’m sorry, I mustn’t knock feminism — but some women writers declare that women want this, women want that, women say this, women say that, as though they speak for all women. This is particularly true of some American academic ladies who are amongst the most privileged people in the whole world, and in the whole history of the world, and who think they speak for all women. In fact there are as many differences amongst women as there are amongst men. There are old women and young women, fit women and weak women, rich and poor. There are women who really get enormous satisfaction out of looking after their parents and their children, and those who do not. Perhaps all would like more space, and I don’t think anyone likes being totally confined to housework. But there are many women who would make a good life seeing the home and their children as the main focus through a large part of their life. There are others who simply don’t find any satisfaction in that at all. It’s rather like saying that all men ought to be gardeners, they’d all actually prefer to be digging gardens. I also think that parenting and relations between the generations are very important to men and women alike and that men, particularly working-class men who rarely saw their children when they were small, missed something very important. They were out at work before the children were up and back at work when they were in bed. I think they missed a whole dimension of human experience.

After the war, and after the defeat of fascism, there was a real feeling of hope that a new world was being constructed. You went to Yugoslavia to help to build a railway there. What do you feel today as Yugoslavia breaks apart and its peoples opt for nationalism? The railroad that you worked on was in Bosnia, a country that you now see being destroyed.

Everyone must be appalled by what’s happening there now. I think both as academics and in our own lives most radicals and communists and socialists of my generation thought that the basic conflicts were class conflicts between the exploited and the exploiters, or between the conquered, the victims of imperialism, and the conquerors. We saw these as the major conflicts. Nationalist and other ethnic conflicts were seen as epiphenomenal, encouraged by the exploiters in order to divide the workforce. I think we probably were very wrong on this, and in our analysis of what in fact impels human action, particularly the kind of absolutely destructive and self-sacrificing activity of the volunteer soldier — as Tolstoy said, war demands not only the ability to die for your country but to kill for it. And what people will kill for actually turns out not to be class issues, or gender issues, but very often these very difficult racial, national, ethnic, religious divisions which seemed to people of our generation very superficial, quite unimportant. If you walk through Bosnia you would not know a Croat, a Serb or a Muslim if they were all drinking together. There would be no way you could tell, except at Ramadan when the children might wear traditional clothes. But the women don’t wear the veil, or they didn’t when I was there. There was no way you could differentiate these people and they all seemed to think, having defeated the Germans, that they were building a country in which these differences were recognized but were not essential. I think there was always a very deep Serb–Croat division; after all, the Ustashe had murdered horrifying numbers of Serbs. You could feel that in the air, but in the main even that was something that they were putting behind them. Well, obviously we were wrong if we thought this was what was happening, because things could not have erupted in the way they have now if those ethnic and religious and linguistic divisions had been as superficial as we thought. But I am still shocked and horrified at the persistence of ethnic hatreds. I suppose it is the same thing on the Indian subcontinent. That India had got its freedom was one of the great triumphs in our lifetime, and yet these antago- nisms have led to thousands of people being killed today and yesterday.

What was the feeling amongst the group you were with from Britain?

There were Fabians, there were Communists. We saw people as good workers or bad workers. My electrician who has a black assistant says we electricians see people as good electricians or bad electricians, we don’t notice their colour. We didn’t really look at people’s politics very much if they were good workers. (I don’t wish to gossip but there were one or two very well-known persons out there then on the Left who were extremely unpopular.) It was a job of work, we were building a railway. We met groups of people from all over the world — but significantly no Soviet people. There were meant to be no Americans either, though a few adventurous ones, typically, managed to squeeze in by bicycling and pretending they were doing something else. Mostly the youth workers were from different parts of Europe and they all worked together, they had campfires together, they sang songs, shouted, went to meetings, or slept through meetings, together. The Romanians and the British always snored deeply when slogans were being shouted out, but there was a great sense of international cooperation and of course an enormous sense of hope.

What was your working day like?

We got up at half past five, washed in cold water, then went off to work at the rock face at six o’clock. We had a break at half past eight, when we had a sandwich of black bread and apple jam and some acorn coffee, and then we worked on till about midday. At midday we went back and had the main meal of the day which was eaten on the campsite — big dishes of tea and vegetables and things. In the afternoon everyone could do what they liked. Some of us went walking, some of us had classes with other groups, some people slept. In the evenings we had camp fires and political speeches and singing and dancing. You did about six hours solid manual work, digging rocks, loading up trucks, pushing them along and tipping them over the embankment, and the rest of the time socialized with the other groups.

And was this where you first met Edward Thompson?

No, we went together, or rather we got there by different routes but we decided to go together. We had already known each other for two years at Cambridge since he’d come back from the army and I’d come back from the drawing office where I was an industrial draughtsperson. I was then married to someone else but it was a very short wartime marriage and broke up without a great deal of difficulty as far as I remember. Edward and I were both interested in history, both members of the Communist Party, I fancied him, he fancied me. I suppose that’s all one can say.

What about getting married?

Well I was married to someone else, as I say, and Edward and I lived together — in those days you couldn’t get a divorce until you’d been married for three years so that I couldn’t just get a divorce from my first husband until the three years were up. By that time I was pregnant with our first son. In fact we got married a week before Ben was born, which puts me in the wrong with the modern generation but also with the last generation. I was too soon for the present lot and too late for the older lot, but that was why we got married. In those days you did feel that if you were having children you should be married because all kinds of legal, property, and identity things were overcome if you were married — the child had a name and if there was any property in the family, it would inherit. Nobody really thought twice about getting married once they were pregnant. I don’t think any of my friends had babies before they were actually married, but most of them married pretty close to giving birth.

In an essay on C. Wright Mills, Edward wrote approvingly that his biography had been very distinctly changed by history, in other words he wasn’t just an academic but his life responded to events in the world. Could one say that this applies to Edward and yourself and in fact to a whole generation of historians, philosophers? To what extent do you regret any of that, the fact that your biographies have been moulded by history?

This may not exactly answer your question but the idea of becoming an academic aged twenty-four and staying there till you’re sixty-five seems to me the ultimate hell — well perhaps not the ultimate hell, there are worse jobs to be stuck in. But the idea of staying in one job and just slogging away at it without a change of scene and a change of emphasis and a change of atmosphere would seem to me absolutely frightful. I know some people do it but for intellectuals the rigid career structure is only a fairly recent development really, except for people like clerical dons. Most people in the past moved in and out of political activity or writing or academic work. For our generation this was still possible. When I first went to Birmingham Charles Madge was professor of sociology. As far as I know he didn’t have a degree but he had worked in Mass Observation and other work and he brought his experience into academe and taught sociology from it. I think that I would not have felt I could write about working-class history and popular movements if I hadn’t spent quite a lot of time taking part in them, not just because it gives you the experience but because it takes you out of the purely academic approach to things. You don’t necessarily write about the things you’ve done but it does help. I think our generation has been very fortunate in that we’ve had a much more varied experience. People were in the army or industry and then moved to academic jobs or political jobs. It’s becoming more difficult for people to do this kind of thing, and I suppose those who do move in and out of different spheres of work feel that they’re more exposed to what’s happening in the world at large than people who just progress from being lecturer to senior lecturer to professor and if they move, move from Oxford to York.

Is there any sense in which you feel that the years before 1956 when you were in the Communist Party were wasted ones?

When people give interviews they often spend their time pointing out that whatever they did was the perfect path and that’s why they’ve ended up as such perfect persons. I certainly wouldn’t claim that. On the other hand I did enjoy a lot of my time in the Communist Party. I met some wonderful people and got to know people of quite different backgrounds and of different nationalities whom I wouldn’t have met otherwise. So in that sense I don’t regret it. I just cannot know what sort of a mind and intellectual development I should have had if things had come out otherwise. I’ve absolutely no way of telling so I can’t say whether I might have ended up as a brilliant scientist or a brilliant historian if I hadn’t been tied down by Communist experience. But I would say I don’t regret it in the sense that I have many very good memories. As a historian I try not to theorize too much about what would have happened. All you can do is understand what you think did happen.

Could you explain how you have tried to explore this relationship between the public and the private in your work?

During the nineteenth century the articulation of the ideology of "separate spheres" and the separation between the public (male) and the private (female/familial) was usually put forward as an argument against the granting of citizen’s rights to women. The rhetoric has to be treated with some care, but I think it is still of some value to recognize areas of public and private concern. I found myself thinking of this when I wrote about Queen Victoria. One reason why she is so fascinating is that she is the first person in history, as far as I know, to undertake both public and private roles simultaneously and in the same office. She is a mother and wife, but she is also the Queen and never steps down from that role. She talks about ruling by example rather than by fiat, although she does in fact take a close personal interest in the politics of government. In spite of the presence of a woman in the highest office of state, however, the mainstream political rhetoric of her reign is concerned with keeping women out of the expanding public areas — the areas of the press, of the constantly expanding constituency of parliament and the electorate, of the increasingly masculinized professions and of the burgeoning local public structures of town halls, local councils and social agencies. Women preachers are forced out of most dissenting churches, and even those with a traditionally strong female presence, like the Society of Friends, see an increasing division, spatial and organizational, between male and female sections of their work. In literature and politics these public/private divisions are constantly emphasized, but the ideal domestic realm over which woman rules does not exist for the working people. While laws are passed restricting factory women’s labour to prevent them from working at hours in which they should be caring for husbands and children, the far greater number of women domestic servants have no such protection and no opportunity of participating in a private sphere except as menials in the family life of their employers. For the poor there was little private life of any kind, and little chance to make choices about moral questions in a family life in which all access to the agencies of choice — legal, medical or social — depended upon money. So if upper-class women, especially the unmarried or talented among them, were restricted by the public/private rhetoric, working-class women might often have welcomed a greater opportunity to do their work and care for their children with more privacy and less interference from outside than they were given. I do think that there is a need for a public/private boundary, though not a gender-based one. There should be areas in which the state has no right to intervene. I don’t think this applies only to sexual and familial questions. I think there ought to be areas of thought and behaviour which are not the responsibility of the state and which the education system has no right to intervene in. I don’t think children ought to be educated in a particular religion. But I also don’t think they ought to be educated to believe that all religions are the same, which is just as bad as teaching them that one is better than the others. You know, I think real secular education is something that we have hardly begun to envisage yet. And it probably should be accompanied by an expansion of facilities for small groups to develop programmes of additional education, which are controlled by the family and not by the state. But this raises enormous questions, enormous problems. If you go too far along the road of minority education then you may disadvantage people who belong to minority groups. If they’re only ever exposed to the social values of a very small and narrow sect, they may be less employable and have less access to the major areas of public life. So I think this, again, is one of the tensions that’s constantly present in every social decision, and one of which we have to be constantly aware.

You have a very critical attitude to any idea that there is continuous progress in history. It is a modern version of the Greek view of history that everything’s tending towards some improvement.

That again is a huge subject. I certainly don’t think anyone living today could see human history as a history of progress. But you can see — the word progress is a very dangerous, very nineteenth-century one. And the various teleologies of which Marxism was certainly one saw history as progressing inevitably and in stages, towards some final state, whether it’s the Kingdom of God, or the classless society, or a realized Utopia. Either you get there or the whole thing blows apart. It’s a very dangerous view and it also leads to a kind of fanaticism and self-sacrifice in the interest of an unknown future, which often means the sacrifice of a present generation. So no, I wouldn’t accept an idea of progress, or a linear, or teleological development, in history. But I wouldn’t go to the other extreme and say that all virtue lies in static societies. Especially for women. I should think of the women peasants, probably 50 per cent might have been happier staying as peasants, and the other 50 per cent would have given anything to get out of the narrow, prurient, and morally deterministic society in which they grew up. There are always these tensions around traditional values, which may benefit many people, but which often isolate and marginalize the creative or the different or the inventive person.

Do you think there are insights in the movement before the emergence of modern socialism in the late nineteenth century which would be relevant to thinking about the problem which you said you thought now faced people — that of how to create a society which people really want to live in?

When you introduce the word create, that’s fine if you’re God, but if you’re anyone else "creating" is problematic. I think one of the most interesting arguments about the practicalities of a desirable social community is that between Edward Bellamy and William Morris which took place in the late nineteenth century. Bellamy saw the future as an urban society in which work is limited. Everyone does three hours’ work a day, in a conscript army that does all the work, and then the rest of the time is spent in leisure activities and people entertaining and amusing each other. They use science to limit the amount of work that needs to be done. Morris responded in fury to this "Cockney Utopia" and wrote News from Nowhere — describing a rural and small-town society in which everybody has fulfilling and pleasant work. Everyone changes their work often enough so nobody gets stuck as a bricklayer all their life, they do other jobs. On the one hand there is the idea that work is an evil that has to be done and has to be got round and, therefore, should be organized in such a way that we all benefit from it, but don’t have to do too much of it. And the other view is that we only exist — we are working animals and are only happy — if we’re working. I think, again, this is one of the tensions within human consciousness. The very rich people in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, who didn’t need to work, nevertheless set up most elaborate structures of seasonal behaviour, from fox-hunting to court attendance for themselves; they had to be in action at a certain time or place — because just doing nothing, or being generally cultured, was not satisfying. So perhaps one fundamental question is how to organize work so that it is rewarding and to a degree satisfying, and perhaps fulfils what may be a basic human need for a certain regularity and a certain challenge in daily life but, at the same time, not to end up with a society in which all the nasty work is done by a section who get no fulfilment and no pleasure. This is, again, one of the tensions, one of the motivating ideas behind socialism, to which different socialist programmes offered totally different answers. I don’t think we have answers but we do constantly have to pose the questions. We have all the time to weigh factors against each other. Structure and routine against freedom, but how much freedom? What sort of freedom do people want? Shorter hours and greater leisure meant more fulfilling and agreeable work for most people. They have for some. But modern work patterns haven’t necessarily meant shorter hours. Some of the people who do the most useful work, or the most necessary work, are still working just as long hours as before, while millions are without work. We haven’t really sorted out the problem of work — maybe it’s not a sortable problem but it points to tensions and contradictions that left-wing and socialist people have to look at.

You have said that the Chartists did not differentiate between economics and politics. They thought bold political changes would be tantamount to social transformation.

I think Chartism came at a time when, as George Eliot says in one of her novels, everybody believed that politics was the route to change, that everything could be achieved by political action. You could regulate factory hours, you could emancipate women, you could introduce freedom — everyone felt that political change would work wonders. And then you have a great swing against that after 1848, in the fifties, sixties, and seventies, towards organized self-help — trade unions and cooperative societies. And partly under the influence of Marxist and Owenite teaching, the idea grew that the decisive area of transformation was the economic sphere. This approach was very general. Thus the liberal free traders believe that free trade will solve all the problems, and you don’t need the state, except just to hold the ring and to sustain a military force to stop your ships getting sunk. But free trade, the free play of the market, was going to be the real answer. Everyone could be encouraged to "build a better mousetrap." Amongst the socialists it was the expropriation of the economic forces that was going to transform society. And politics really did take a back seat for the labour movement until after the First World War, and even then the political programme was always tentative. The Labour Party never really saw it as possible to bring about political change because socialism was always in the way. Labour politicians tended to believe that you had to have socialism before you could really make political change. In the twenties and thirties, socialism was never really on the agenda and they could not proceed without the expropriation of the expropriators. They tinkered around with social and economic policy, but without really making any attempt at fundamental change. It’s not till 1945 that you begin to get an attempt, through politics, to alter social structures and change social attitudes. By the time you get to the forties, you’re swinging back one hundred years because, in those days, the Chartists didn’t see the industrial and political as being two discrete entities. They thought you could limit the rapacity of capitalists by limiting the hours of work, by legislating about wages, by regulating women’s labour, by introducing compulsory education. All these kinds of things they saw as political moves, which would improve their social situation; post-1945 we came back to this approach, with an interaction between political and social and economic factors. The Thatcher period has seen drastic political action coming from the Right to reshape society and the economy. I think you’ve never had a period in human history — well in British history anyway — when there was so much ideological politics exerted on the economy as there has been in the last fifteen years. The economy has been totally sacrificed to political dogma, and I think this again is one of the tensions that has to be resolved. The whole of socialist history is about achieving some sort of balance and coordination between social mobilization, political action, and economic transformation.

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]