“Down with the Pipe and the Poodle!”: Yugoslavia, 1968

The events of June 1968 in Yugoslavia both revealed the contradictions of self-management socialism and affirmed the vitality of official socialist discourse as a language of critique.

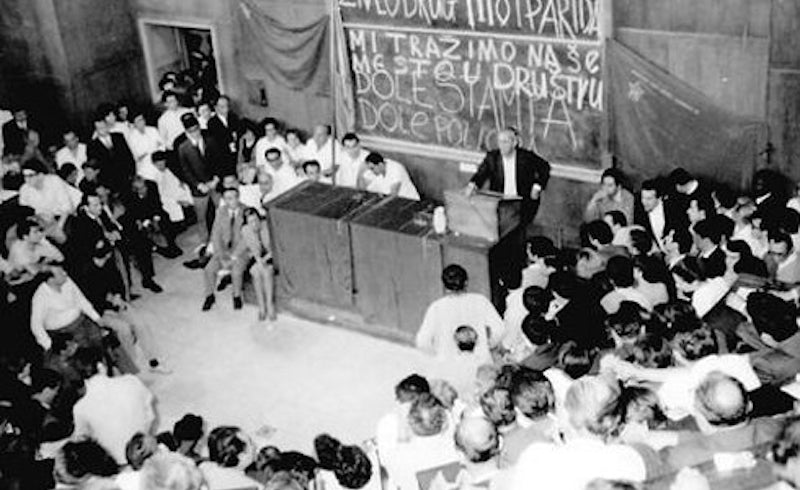

On a humid night in June, 1968, in a northern Belgrade suburb, a brawl at a concert hall quickly escalated into a violent confrontation between college students and city police. By noon the next day, students throughout the city had occupied their campuses and dorms, demanding the sacking of the chief of police and calling for a radical democratization of socialist Yugoslavia’s political structures.

Despite efforts by the ruling League of Communists to contain the unrest to the capital city, within days the protests had spread throughout the campuses of Yugoslavia. Across the six republics of the federation, students, organizing outside of the official student unions and party organizations, condemned what they termed the “red bourgeoisie” and declared their solidarity with the working class. In Belgrade the occupied Faculty of Philosophy was renamed the Red University of Karl Marx, red flags and portraits of Marx, Lenin, Tito, and Che Guevara were hung from its walls and sympathetic faculty organized lectures and study groups on Marxist philosophy.

Although the protest lasted little more than a week, its demands eventually being safely channelled into the official institutions of the self-management system, the impact of June 1968 would continue to profoundly shape the contours of opposition politics and youth counter-culture well into the 1990s.

—

More than just a node in the transnational protests of this revolutionary year, the events of June 1968 revealed the contradictions of self-management socialism and affirmed the vitality of official socialist discourse as a language of critique and ideological interpellation in Yugoslavia.

The institutions of self-management socialism were fashioned in the aftermath of the conflict between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union in the summer of 1948. Provoked by Moscow’s heavy-handed approach towards its East European satellites and Stalin’s growing paranoia of Tito’s popularity, the Tito-Stalin split was the first international rift between two communist states. For the Yugoslavs, it spurred an ideological reckoning with the Soviet model of socialism.

Critical of the bureaucratic and authoritarian structures of the Soviet state, in the years following 1948 Yugoslav leaders sought to forge a new path to socialism. Highlighting the importance of the Marxist theory of the “withering away of the state” during the transition to communism, the party embarked on a series of reforms that sought to disaggregate state institutions in line with a decentralized, participatory model of socialism.

As part of these reforms, in November 1952 the League of Communists abandoned its monopoly on state institutions. The separation of party from state was intended to avoid the bureaucratization that Yugoslav theorists believed had deformed the Soviet party. From now on, the League was no longer formally guaranteed control of state institutions; although it would continue to be the sole legal political party, cadres would now, in theory, have to win influence through discussion and debate within the forums of self-management.

Despite official rhetoric, this reform was not primarily a move towards greater democracy. Rather, its goal was to maintain the interpellative power of official discourse by untethering it from the structures of the state. It was, in this regard, an effort to avoid the ossification of official socialist discourse in the Soviet Union.

Writing of this discursive ossification, the anthropologist, Alexei Yurchak, has suggested that Soviet official discourse underwent a “performative shift” in the years following the death of Stalin. Drawing on J.L. Austin’s distinction between performative and constative speech acts, Yurchak argues that in the period of late socialism in the Soviet Union, official discourse effectively lost its constative or descriptive dimension; no longer capable of accurately describing social reality for the subjects of the state, socialist discourse became a reified language of political ritual and routine.

According to Yurchak, this drift between the constative and performative in socialist discourse was the result of the crisis of ideological authority that beset the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death. As the sole master-signifier of Soviet ideology, Stalin had occupied a place of metatextual authority, capable of stitching in place the meanings of official discourse. With his death, this discourse became increasingly detached from a point of authority.

Thus unmoored, the language of socialism increasingly took on a mere performative dimension, functioning more as a formal language of political ritual and routine than a means of ideological interpellation or a transparent description of reality. This performative reduction was beautifully satirized by Vaclav Havel in the figure of the Czech greengrocer who, despite his contempt for the communist regime, routinely placed in his window a sign with the official slogan: “Workers of the world, unite!” Reduced to a language of ritual, Yurchak argues, official discourse in the Soviet Union lost much of its ideological power.

The formal decoupling of the party from the state in 1952 reflected the anxieties Yugoslav communists felt towards this kind of bureaucratic ossification of their own revolutionary discourse. In contrast to what they perceived as the monolithic bureaucracy of the Soviet state, reformers like Edvard Kardelj and Milovan Djilas insisted on the need for the party to maintain an organic link with the population, to eschew dogmatic or doctrinal language and to foster mass participation in the decentralized structures of the state. By severing the party from the monopoly of state power, cadres would be forced to engage the population and, in the process, to renew and revitalize state institutions and official discourse.

However, this professed vision of a self-managing state contrasted markedly with the continued dominance of Yugoslav communist officials within its ranks. Social mobility through the civil service or socially-owned economy still largely turned on one’s membership in the League, and the echelons of state power remained the sole purview of the party leadership. At the same time, the decision to detach official discourse from the authority of state institutions meant that these same institutions could now become the object of socialist critique.

The history of self-management socialism is, in many ways, a history of Yugoslav communists’ repeated attempts to revolutionize their own discourse, to re-engage the population and to institutionalize vibrant ideological debate, all the while circumventing the concrete effects of this debate and preventing it from challenging the leadership’s preferred policies. The state swung like a pendulum between the cultivation of the mass participation of society and its pacification, marginalization, and occasional repression.

This pendulum effect explains the events of June 1968, a rebellion that turned the official meanings and interpellative power of socialist discourse against the state.

—

The protests of 1968, however, pose a theoretical challenge to Yurchak’s model. If, in socialist Yugoslavia, official discourse still had the capacity to interpellate a generation of youth, what were the ideological points of authority in which this discourse was anchored? It was not enough that Yugoslav reformers had seemingly avoided the bureaucratic degeneration of the Soviet Union; to have purchase on its subjects, official discourse must have been moored in a set of master signifiers beyond the state.

These new points of ideological authority through which the Yugoslav leadership was able to stitch into place official meanings were found in the global politics of Third Worldism.

Throughout the 1960s one of the means Yugoslav communists used to foster mass participation was through campaigns of solidarity with the Third World. These campaigns grew out of the country’s diplomatic orientation towards the states and liberation movements of Asia, Africa, and Latin America from the mid-1950s onwards. Within the framework of the Non-Aligned Movement, of which it was a founding member, socialist Yugoslavia aligned itself internationally with the struggle against both European colonialism and US and Soviet imperialism.

Membership in the Non-Aligned Movement redirected the antennae of Yugoslav ideology towards the post-colonial world. Newspapers closely followed events in Congo, Angola, Cuba, Algeria, Palestine, and Vietnam. Hundreds of students from Asia, Africa and Latin America came to study in Yugoslav universities, where they quickly established political and social organizations. These students also worked alongside their Yugoslav colleagues in the Student Union’s Clubs of International Friendship, which organized educational events devoted to the politics and cultures of the post-colonial world.

Third Worldism, a language of opposition in the Western democracies, became part of the official discourse of Yugoslav socialism, and throughout the 1960s the League of Communists sought to mobilize the population in campaigns to promote solidarity with the Third World.

Such efforts, however, while highlighting the popular appeal of the Third World as a source of ideological legitimacy for the regime, also exposed its contradictions.

On 14 February 1961, for example, Yugoslav citizens were called on to join mass demonstrations around the country to protest the assassination of the Congolese prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. In Belgrade alone, close to 150,000 people filled the streets, chanting anti-colonial slogans and declaring solidarity with the Congolese independence movement. Events became messy, however, when around 30,000 young protesters broke away from the main rally and marched to the Belgian embassy, which they began to pelt with rocks. After police were called to disperse the crowd, vicious brawls broke out between police and demonstrators.

This protest set the tone for future confrontations that took place between students and police throughout the decade. In November 1964 in front of the US consulate in Zagreb, police violently broke up a rally of African and Yugoslav students protesting the continued occupation of Congo. Two years later, in a week of solidarity with the Vietnamese national liberation struggle, police and students clashed violently in both Zagreb and Belgrade.

In these demonstrations, party-led efforts to cultivate mass social support for official ideological causes conflicted with the state’s goal of preserving friendly relations with Western imperialist powers. Calls for Third World solidarity on the domestic front therefore constantly threatened to engulf the state in diplomatic crises.

The attempt to anchor official discourse in the signifiers of global Third Worldism successfully sutured the meaning of Yugoslav socialism, but in so doing placed both state and party under greater ideological scrutiny from its own subjects.

—

The confrontations that took place between police and students in the context of official Third World solidarity campaigns prepared the ground for the events of June 1968. Not only had these earlier conflicts fed a general distrust for the police among young people, they had also cultivated a widespread ideological suspicion of the state and party.

The protests of 1968 were therefore a rebellion against a socialist state from within that state’s own ideological coordinates and discursive meanings. When students in June 1968 unfurled banners reading “Workers, we are with you!," this was not a form of everyday political ritual, akin to Havel’s cynical greengrocer; it was both a description of and an effort to transform reality in line with socialist ideology, to inspire a struggle of workers and students against the state bureaucracy and “red bourgeoisie.”

Although Yugoslav students were clearly inspired by student movements in the US, West Germany and France, all of which received favourable coverage in the Yugoslav press, the discursive scaffolding for the rebellion was built on domestic ideological foundations, in particular the official Third World campaigns of the 1960s.

Symbolic traces of these campaigns can be seen in the Belgrade students’ decision to hang a portrait of Che Guevara in their occupied faculties. The presence of the Argentinian revolutionary was a clear nod to the Third Worldism that punctuated counterculture politics throughout the late 1960s. At the same time, the portrait had a subtle meaning in the Yugoslav context. Hung, as it was, alongside a portrait of a younger, wartime Tito, the image of Che also helped to conjure the spectre of a more spartan, heroic, and revolutionary period of Yugoslav socialism.

This pairing of the young Tito with Che on the walls of the occupied university was complemented by a rather curious slogan chanted by the students during the protests: “Down with the pipe and the poodle!”

The chant referenced a recent photo of President Tito, seated in a leather armchair, smoking a cigar and laughing heartily while by his feet a fluffy white poodle stared bewilderedly into the camera. The image captured the comfort, leisure and decadence of the “red bourgeoisie” that was the focus of students’ ire. It contrasted markedly (and unfavourably) with the romanticized images of foreign revolutionaries from Congo to Vietnam to Bolivia, which Third World solidarity campaigns had cultivated throughout the 1960s.

In this image of the young Tito, Yugoslav students raised the legacy of the anti-fascist struggle of WWII, evoking a revolutionary history more in tune with an era of Third World liberation struggles.

James M. Robertson is Assistant Professor Politics and History at Woodbury University in Burbank, California.

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]