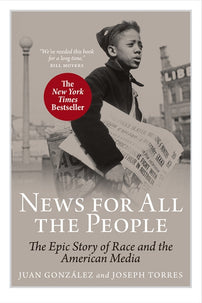

News For All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media

In this excerpt, Juan González and Joseph Torres argue for the importance of understanding the history of race and the American media system in order for a “democratic revolution of the U.S. media” to succeed.

From colonial newspapers to the Internet age, America’s racial divisions have played a central role in the creation of the country’s media system, just as the media has contributed to—and every so often, combated—racial oppression. News For All the People—called a “masterpiece” by the esteemed scholar Robert W. McChesney and chosen as one of 2011's best books by the Progressive—reveals how racial segregation distorted the information Americans have received, even as it depicts the struggle of Black, Latino, Asian, and Native American journalists who fought to create a vibrant yet little-known alternative, democratic press. News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media is one of the core texts on our student reading lists and 50% off for the month of September as part of our Back to University sale. See all our Film and Media reading here.

Here we present an excerpt from the Introduction:

By the end of the nineteenth century, our country was a growing world power with a new overseas empire. Rapid and reliable communications between parts of that empire became not simply an economic necessity but a requirement of imperial military strategy. Nonetheless, the first decades of the twentieth century witnessed more involvement by blacks and Hispanics in radio than is generally acknowledged. Scores of African-Americans were active in the amateur radio movement after World War I, and the Commerce Department issued the first commercial radio license to a Hispanic in 1922—more than twenty years earlier than commonly believed. But once the federal government moved to regulate access to the airwaves with the creation of the Federal Radio Commission in 1927, people of color were completely shut out of ownership in the growing industry; even their presence on the air was sharply reduced.

The massive entrance of blacks and Latinos into the military during World War II prompted some improvement in media portrayals of nonwhites, as the government, responding to widespread social unrest and race riots during the war, pressured radio owners to provide more diversity in news and entertainment programming. On the heels of that effort, Raoul Cortéz became the first post-war Latino commercial radio owner when he launched KCOR-AM in San Antonio in 1946, and Jesse B. Blayton became the first African-American owner of a station license in 1949, with WERD in Atlanta.

It would take a new wave of urban riots twenty years later, and a pivotal battle in the federal courts to integrate Mississippi television, before the nation finally took significant steps toward the racial integration of our media system. In 1968, the US Commission on Civil Disorders strongly criticized the role played by the media in covering minority communities. “Along with the country as a whole, the press has too long basked in a white world, looking out of it, if at all, with white men’s eyes and a white perspective,” the Commission warned. That is no longer good enough. The painful process of readjustment that is required of the American news media must begin now. They must make a reality of integration—in both their product and personnel. They must insist on the highest standards of accuracy—not only reporting single events with care and skepticism, but placing each event into a meaningful perspective.19 The Commission urged immediate steps to increase the presence of minorities in the newspaper and broadcast industries. Its call led to sweeping media reforms by government leaders and press barons in the late 1970s.

Thus began what we have called the new democratic revolution in the American press. That revolution included the adoption of federally mandated affirmative action programs to speed up minority employment and ownership in broadcasting, bold new programs by universities and associations of media executives to improve industry hiring practices, and the rise of Spanish-language television. The period also witnessed hundreds of challenges to local station licenses by minority communities—even some sit-ins and occupations of some stations. The unprecedented upsurge literally forced broadcast owners and publishers to hire and promote non-white journalists and to improve coverage of racial minorities.

Once that first generation of black, Latino, Asian and Native American journalists entered those newsrooms, they encountered such enormous hostility from white colleagues that they were forced to create their own professional associations as their only support networks. Those associations quickly grew in size, and assumed central roles as watchdogs and pressure groups within the industry to monitor news coverage and hiring practices. All popular movements, however, provoke organized resistance from defenders of the status quo. By the 1980s and early 1990s, conservative politicians had begun rolling back several federal regulations aimed at assuring racial integration and diversity of ownership in newspapers and broadcasting. At the same time, the cable industry, which had initially ushered in a new era of diverse ownership and programming, became dominated by a few giant companies.

Some believe that the emergence of the Internet in the final decades of the twentieth century has offered hope for a return to a decentralized system of news dissemination. But cyberspace, as we show in the final chapter, has quickly evinced the same kind of unequal racial divide in ownership and content that has marked the rest of our media system.

The persistence of racial inequality in the news industry is part of a broader crisis facing American journalism. Thousands of professional journalists are today losing their jobs. The survivors find it increasingly difficult to produce the kinds of meaningful information the American people need. And while Internet blogs and websites run by citizen journalists are increasingly generating important news that the commercial media ignore, such sites have yet to provide an economic model for sustaining thousands of full-time journalists in the pursuit and production of news—a model that could replace what Old Media have done for 200 years.

The central role of the press in our society makes this industry-wide crisis a crucial problem for the entire nation. Thankfully, many citizens already understand this. In the first decade of the twenty-first century a new and powerful citizen movement for media reform came of age. That movement, which arose during a battle to prevent the FCC from deregulating broadcast ownership provisions, already counts millions of Americans from across the political spectrum in its ranks. The members of this new movement are deeply disturbed by the concentration of ownership in our news media. They are frustrated and angry over the endless hyper-commercialism, infotainment and obsession with violence and sex that dominate its content. They worry that despite the great potential of the Internet, the largest communications companies exercise too much control over news and entertainment. They fear that these big media firms, along with the cable, telecom, and satellite broadcast companies that control the “pipes” through which news, audio, video and Internet data reach every home, are displaying only disdain for the public-service responsibilities of the press, eliminating local voices, driving out diversity of viewpoints, undermining our democracy.

With each day that passes, with each new advance in mass communications technology, our biggest media companies feverishly race to readjust, to become bigger and more dominant in the marketplace. Only by clearly grasping the main conflicts and choices that shape our current media system can ordinary citizens successfully unite with the concerned journalists and workers within the system to bring about meaningful reform. The second democratic revolution of the US media has already begun. Those who hope to triumph in that revolution must first understand how our system of news reached its current state. It is an amazing saga, brimming with picturesque rascals and wide-eyed visionaries, with legendary big-city publishers and obscure immigrant editors, with writers of astonishing courage and legions of cowardly charlatans, with brilliant statesman and the worst of racial arsonists.

News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media is one of the core texts on our student reading lists and 50% off for the month of September as part of our Back to University sale. See all our Film and Media reading here.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]