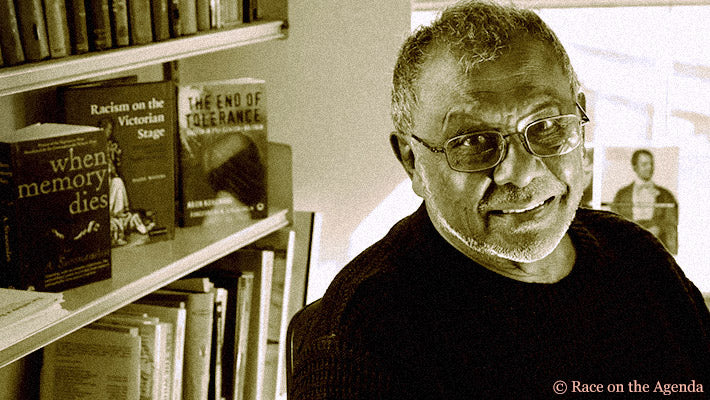

In Memory’s Wake: Remembering A Sivanandan

Today marks the one year anniversary of the death of one of Britain's foremost black socialist intellectuals, A. Sivanandan, whose work changed the way we think about race. In this essay, Fathima Cader reads his work via his novel When Memory Dies, which charts the struggles of three generations of Sri Lankans.

Today we mark the one-year anniversary of the passing of A Sivanandan, late director of the Institute of Race Relations and editor of the journal Race and Class. While perhaps most well-known for his work in the UK, it was his experiences growing up in Ceylon that shaped the Marxist analyses for which he became beloved in Britain.

Sivanandan immigrated in 1959:

my parents’ house was attacked by a Sinhalese mob, my nephew had petrol thrown on him and burnt alive, and friends and relatives disappeared into refugee camps. I was a Tamil married to a Sinhalese with three children, and I could only see a future of hate stretching out before them. I left with my family, and came to England.

In his 1997 novel, When Memory Dies, Sivanandan draws on this personal background to tell the story of three generations of a Tamil-Sinhalese family navigating the erosion of land-based communities under colonisation, industrial acceleration, and globalisation. Though fiction, Sivanandan’s book tracks closely against Sri Lanka’s real-world political history over the better part of the last century.

In 1948, the island was granted independence from British rule. The novel digs into the murkiness of the island’s development, from the once-laudable then-questionable role played by trade unions, the entrenchment in law of Sinhala Buddhist majoritarianism, and the advent of war between the Sri Lankan state and Tamil separatists. Where When Memory Dies stands apart from other English-language novels about Sri Lanka is in its tracing key roots of the island’s war to class struggle.

“They were paying us starvation wages and treating us like animals. We couldn't take it any more, and finally, in despair, we found the strength to strike,” says SW, a senior Sinhalese trade unionist about Colombo’s railway strikes from the 1910s.

That kind of strength – hewed in desperation and honed in collective action – threads through all of Sivanandan’s work, from this novel to the fiery anti-capitalist orations for which he is better known. In 1990, Sivanandan discussed Britain’s efforts to deport Tamil asylum-seekers back to the war they were fleeing:

the whole issue of the would-be-refugees, tortured by the Sri Lankan government, brought up Britain's role in the training of the armed forces and intelligence networks of repressive regimes and the implications of tourism in such countries. And when two Tamil asylum-seekers working (for want of work permits) as night security guards in a Soho amusement arcade were burnt to death, the issue became one of the superexploitation of a new rightless, peripatetic section of the working class and led to an exposé of the profits made by the leisure industry.

To date, Western states continue to deport Tamil refugee claimants back to Sri Lanka, despite credible documentation that underground torture sites remain active even now.

Never one to divorce race and class, Sivanandan was in effect posing a question about how we map death-making: are we as willing to see the killing-machines of the everyday, as we are quick to decry them in warzones?

From its very first page to its last, the book’s often meandering plot is ultimately tied together by a focused attention on the multi-pronged oppression of the island’s Tamil plantation workers. This is significant: state and societal marginalization of the island’s Indian-descended Tamil estate workers is often glossed over in political histories of the war. Commencing in the 1800s, Britain brought indentured labourers from South India to work tea plantations in the island’s central highlands.

Isolated and exploited, the plantations unsurprisingly became active sites of trade unionism. Fearing an electoral overthrow by increasingly popular leftist parties, Sri Lanka’s first prime minister, DS Senanayake, stripped the estate workers of voting rights and citizenship a year after independence.

Senanayake spuriously claimed that the estate workers, who had lived on the island for generations, represented an Indian invasion. “It was the British who took our land, not the coolies,” decries a Sinhalese university student in the novel, inviting a beating from a neighbour.

Despite notable pockets of resistance, Senanayake’s bills was largely met with support, including by numerous leading Tamil politicians and by mainstream trade unions. The novel focuses on the latter betrayal, following the three protagonists’ disenchantments with the anti-Tamil racisms that riddled the allegedly non-communal trade unionism of the urban Colombo and the militantly Marxist People's Liberation Front (aka JVP) of the rural south.

Out of an abundance of caution, successive Sri Lankan governments pursued the en-masse deportations of over half a million Tamil estate workers to refugee camps in India. Democracy (ala one-person-one-vote) had provided convenient cover for Buddhist Sinhalese majoritarian rule.

Entire neighbourhoods of so-called “Indian Tamils” – now stateless – were attacked by Sinhalese mobs. The novel describes how some characters escape, setting out for Jaffna, heartland of the rising Eelam Tamil resistance. There, many receive a lukewarm reception, finding themselves in “a sort of no-man’s-land between the Tamils and the Sinhalese,” as estate worker Sanji says in the book. “I suppose that is what we coolies are, neither one nor the other.”

When Memory Dies is a heart-rending exploration of how precarity of work and precarity of migration operate in mutually constitutive relation to each other. In the wake of the mass deaths at sea, at border walls, and in factories that characterize our current global political moment, it remains timely.

The dispossession of estate Tamils provided an essential precedent for the legalized violence subsequently wreaked on other Tamils on the island. The government had flexed a muscle, and found itself able to pull the wool over a whole country’s eyes: here was racism in the service of class, communalism in the name of nationalism.

And all the while, the state adopted the title of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.

It would have been simpler to begin the story of this war with the 1983 anti-Tamil pogrom in Colombo, which popularly marks the formal beginning of war between Sri Lanka and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. But Sivanandan chose to begin and to focus his novel on the older exploitation of this multiply-marginalized class of workers.

As foreign for their “Indianness” as for their Tamilness, as vulnerable for their being indentured as their being regionally isolated, their story provides a map of the tactical (and ethical!) importance of insisting our movements centre the oppressions of our most marginalized comrades. Whether that marginalization operates along the lines of gender or caste, religion or sexuality, claiming “we will fix that later” is a recipe for disaster: when we internalize the oppressor’s hierarchies, we concede a defeat. We let the oppressor set the terms of battle when we relinquish the strength a mass movement based on clear-eyed solidarity for the disintegrations of authenticity, respectability, and middle-class control.

Sivanandan’s novel is the story of personal and political heartbreak, but it is not a politics of pity or despair. As Ki. Pi. Aravinthan has written elsewhere about embattled Jaffna: "Aren't all these things real, right in front of me, sprawled out and soaked in the hot sun, as sand and stone, as plants and trees, as bushes and palms, keeping me yearning and active?"

Survival can be its own beauty, and unrelenting.

Survival, for Sivanandan, had meant leaving Sri Lanka, and it meant throwing his lot in with another marginalized group in the UK:

I chucked in my job, sold whatever belongings I had and just pushed off to England. And I came and lived in Bayswater and walked straight into the ‘riots’ in Notting Hill. That was, I suppose, a double baptism of fire – Sinhalese-Tamil riots there, white-black riots here. And I knew then I was black.

Audre Lorde meanwhile was noting the problems with defining “Black” as a political position:

It takes the cultural identity of a widespread but definite group and makes it a generic identity for many culturally diverse peoples, all on the basis of a shared oppression. This runs the risk of providing a convenient blanket of apparent similarity under which our actual and unaccepted differences can be distorted or misused. This blanket would diminish our chances of forming genuine working coalitions built upon the recognition and creative use of acknowledged difference, rather than upon the shaky foundations of a false sense of similarity. [1]

Analytical gaps are evident as well in Sivanandan’s comments about the War on Terror, whose resonances with the war in Sri Lanka he should have been attentive to. Instead, after 9/11 Sivanandan called for a “European Islam” that “would divert the anti-imperialist struggles of the Muslim world from individual acts of terror to mass collective action that finds common cause with the anti-globalisation, anti-imperialist movement.” Two decades earlier, Edward Said had pre-empted this kind of decontextualized homogenization:

In no really significant way is there a direct correspondence between the "Islam" in common Western usage and the enormously varied life that goes on within the world of Islam, with its more than 800,000,000 people, its millions of square miles of territory principally in Africa and Asia, its dozens of societies, states, histories, geographies, cultures. […] How really useful is "Islam" as a concept for understanding Morocco and Saudi Arabia and Syria and Indonesia?”

Instead of reproducing the kind of culturizing argument whose liberalism he was otherwise wont to challenge, Sivanandan might have had something to glean from Talal Asad’s vision of a “political Islam” whose possibilities “may lie not in the aspiration to acquire state power and to apply divinely authorized law through it but in the practice of public argument, and in a struggle guided by deep religious commitments that are both narrower and wider than the nation state.”

Sivanandan’s comments belie long-standing and ongoing anti-imperialist organizing by Muslims – not the least of which included his Black Muslim contemporaries, from independence movements in Africa to Black liberationists in North America.

His comments also contribute to the erasure of the Tamil-speaking Muslims who joined or otherwise supported various Tamil liberation groups on the island. In finding common cause with the fight for Tamil self-determination, many of these Muslims, like Sanji, found themselves “neither one nor the other,” made alien by virtue of their religion, an alienation that continues to have repercussions to date.

We mark, then, the passing of an imperfect hero, a man who in recording the massacres of capitalism and war was not himself without contradiction. But we take guidance from his character Vijay:

He understood contradiction out there in society, but he did not grasp it in himself, in people. He had not till now seen conflict as necessary to one's personal growth, as an essential part of life, its motor, as natural as breathing. He had not seen the dialectic was also a felt sensibility and, unless he grasped that, he would not be able to change anything.

--

Fathima Cader is a union-side lawyer and adjunct professor based in Toronto.

[1] See also Momtaza Mehri’s recent essay on Sivanandan, MIA, and their respective uses of Blackness.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]