Chickens Come Home to Roost: the U.S. Empire, the Surveillance State and the Imperial Boomerang

From the Philippines to the War on Terror, the U.S. state has utilised its vast imperial domains as grounds for experimentation for coercive social control.

This is the third article in a five-part series examining the ‘imperial boomerang effect’ and its operation in a range of contexts.

The people of the United States pay dearly for domestic privilege and the securing of imperial domains.

Noam Chomksy

In the popular imagination, it is often assumed that the United States eschewed imperialism. A figure such as journalist and historian Max Hastings can even claim that as a republic built in the heat of revolt against the British Empire, the U.S. has been 'passionately anti-imperialist'.

Reality, however, presents the polar-opposite. From the start of the independent republic, expanding West – from ‘sea to shining sea’ – across Native American land was a major national objective. Indigenous people were dispossessed, slaughtered, and confined to tiny reservations. Once huge tracts of land had been grabbed from Mexico, and the borders of the modern U.S. established, the rising power increasingly cast its gaze further ashore, to the Caribbean, Southeast Asia and the Middle East. Today, with around a thousand overseas military bases, control of cyber- (and outer-) space, mastery of global shipping routes, Earth-spanning mass surveillance capabilities and domination of the international currency, financial institutions and governance structures, the U.S. possesses an informal empire of world-historic proportions.

This imperialism has been a defining feature of its domestic polity. The white population have had their identity, beliefs and subjectivities constructed in relation to the subjugated other, whether they be Indigenous Americans, enslaved Africans, defeated Mexicans or Filipino ‘little brown brothers’. The U.S. state, for its part, has utilised its imperial domains as grounds for experimentation for coercive social control: surveillance, counterinsurgency and weapons technologies have been tried and tested in its formal and informal colonies before being circulated back to the domestic U.S. mainland and deployed against unruly citizens of various progressive shades. This crucial process – the ‘imperial boomerang effect’ –must then be considered a key strategic question for the U.S. progressive movement today.

The Philippines and the formation of the U.S. Security State

The rhetoric of U.S. anti-colonialism was never anything more than a justification for the U.S. take-over of formerly European territories in the global South. Through the 19th century, anti-European colonialist sentiments encapsulated in the 1823 Monroe Doctrine morphed into the barely-concealed U.S.-expansionism of the 1895 Olney declaration: ‘the United States is practically sovereign’ in Latin America, the Secretary of State announced, and ‘its fiat is law upon the subjects to which it confines its interposition’.

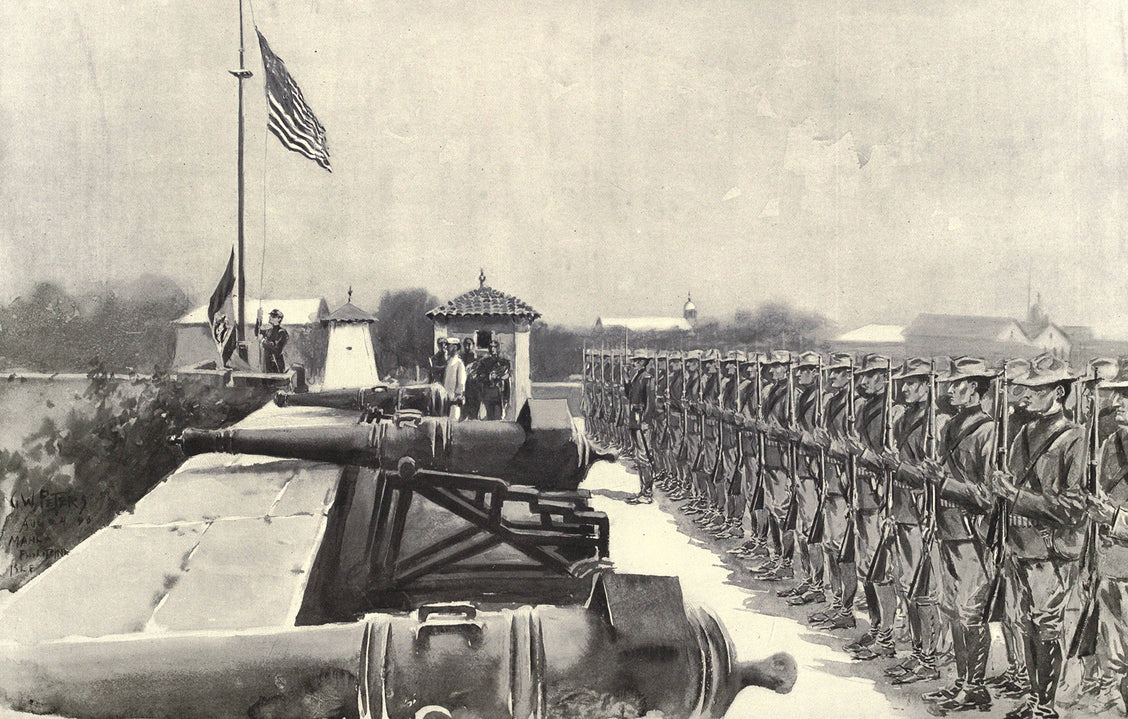

As the 20th century approached, U.S. elites were willing to take the jump to formal Empire. In 1898, Hawaii and Puerto Rico were annexed to the United States, and Cuba de facto seized from a declining Spanish Empire. Only in the Philippines did the U.S. establish a formal European-style colony, however. Home to one of the first national anti-colonial revolutions in Asia, the Philippines presented itself as a useful outpost for the U.S. military on the other side of the Pacific, a gateway to East and Southeast Asia with its own exploitable natural resources and labour power.

The 1898 Spanish-American War quickly became an imperial war of conquest by the U.S. in the Philippines. Not content to swap their Spanish imperial masters for U.S. colonisers, Filipinos fiercely resisted the new invaders, and the U.S. waged a bloody war to subdue Philippine resistance until the 1910s. Not only were around 250,000 Filipinos were killed, but the use of water-boarding was pioneered and village burning made a staple of the US counterinsurgency offensive. Entire population centres were, according to Filipino historian Luis Francia, ‘forcibly evacuated into designated centres or towns that were transformed into virtual prison camps.’ Areas outside these camps were declared ‘zones of death’.

It would be decades until historians discovered how the U.S. utilised the latest technological breakthroughs in communication, social science and surveillance to create a nation-wide apparatus for monitoring, classifying and eliminating Filipino resisters. Alfred McCoy demonstrates in his stunning study, Policing America’s Empire, that the Philippines became ‘a social laboratory at a critical juncture in U.S. history, [producing] a virtual blueprint for the perfection of American state power’. Cartography, census-taking, tax rationalisation, media-monitoring, propaganda, informant networks, vice prohibition and surveillance technologies were amalgamated in an epic act of American conquest.

Ultimately, McCoy writes,

Some of these clandestine innovations migrated homeward, silently and invisibly, to change the face of American internal security. During the country’s rapid mobilization for World War I, these colonial precedents provided a template for domestic counterintelligence marked by mass surveillance, vigilante violence, and the formation of a permanent internal security apparatus.

The pressure of the imperial crucible, like iron forged in a blast furnace, crystallised new tools for the U.S. ruling class to wield in the battle against its domestic population. The radical uprising of West Virginia coal miners in 1920, for example, was put down with methods perfected in the Philippine pacification.

The structures of domination generated by the imperatives of imperial conquest shifted the field of struggle decisively against domestic radicals. Thanks to the existence of the U.S. Empire, radicals in the States had to contend with a repressive apparatus capable of subjugating entire populations and decades-old revolutionary movements in the global South.

The U.S. (neo)Empire, the War on Terror, and the ever-circulating boomerang

The imperial boomerang continued to bounce between the U.S. and the global South long after the Star-Spangled Banner was formally lowered in the Philippines in 1946. From 1962-74, the federal Office of Public Safety (OPS) ran a huge international police training programme for dictatorships in Vietnam, Argentina, Brazil, Iran and elsewhere. An OPS Director would later note: ‘working with the police in various countries we have acquired a great deal of experience in dealing with violence ranging from demonstrations and riots to guerrilla warfare. Much of this experience may be useful in the US.’ One wonders how much of the FBI’s ‘Counter Intelligence Programme’ (Cointelpro) – a vast surveillance, blackmail, defamation, harassment, imprisonment, infiltration and assassination effort directed against all flavours of U.S. radicals – owed to the techniques and tactics perfected in the U.S.’s imperial laboratories.

The U.S. Empire’s boomerang is not confined to the 19th and 20th centuries. The American Empire has, in recent years, boomeranged immense amounts of superfluous military equipment formerly deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan back across its borders, and, as Alex Vitale documents, brought military-style aggression to U.S. schools, side-walks and homes. Today, local police forces cruise around small U.S. towns in bomb-proof quasi-tanks recycled from Iraq and Afghanistan. SWAT teams carry out raids armed with military-grade assault rifles and body protection. It is no surprise that Muslims, hailing from regions ravaged by the U.S. state’s most flagrant imperial adventures in the 21stcentury, are those suffering some of the most intensive racialised surveillance in the U.S. today. The War on Terror’s chickens are roosting in the United States.

The U.S. has also been using its imperial domains as testing grounds for the latest mass surveillance technologies. The NSA, for example, records and stores every single phone callin Afghanistan and the Bahamas, creating a virtual time-machine capable of retroactively accessing any telephonic communications from the past month. The agency has been testing digital interception technologies in Mexico, Kenya and the Philippines, all nations colonised or invaded repeatedly by the U.S. and Britain. It will not be long before such technologies are deployed within the U.S. and British mainland, if they are not already. The Real Time Regional Gateway (RT-RG), for example – an intelligence collection platform used by the U.S. in Afghanistan and Iraq – was deployed overseas for five years before becoming a quotidian corollary to security operations on the U.S.-Mexico border. In an interview with the Intercept, Elizabeth Goitein, co-director of the Liberty and National Security Program at the Brennan Center, said the tale of RT-RG was a classic case of ‘surveillance methods originally conceived as tools of war or foreign espionage’ being ‘brought home and turned inward’. In other words, the imperial boomerang effect.

U.S. radicals of the 1968 generation slowly began to draw the dots between the U.S. Empire, rampant domestic racism and the apparatus of repression, an analysis which had serious implications for their strategic orientation. In order to develop a mass movement capable of reaching the majority of society – and uniting oppressed populations of colour with a decisive segment of the working class white population – racism had to be overcome, and the coercive apparatus of repression instantiated in the police, prisons and intelligence services circumvented. In order to do this, U.S. imperialism had to be fought and brought to its knees. Without confronting the imperial relation at the heart of the U.S. polity and state, the disease of imperial racism would continue to seep deep within the psyche of the white population. Without challenging the imperial experimentation grounds in which the U.S. ruling class freely tested its latest technologies of repression, any militant domestic movement risked being crushed with sophisticated techniques of counterinsurgency. This strategic insight remains vital for any movement that wants to overturn militarism, inequality, exploitation, climate change and injustice inside the U.S. today.

Connor Woodman is an independent researcher, writer and the author of the Spycops in context papers, available at: https://www.crimeandjustice.org.uk/publications/spycops-in-context

This is the third article in a five-part series examining the ‘imperial boomerang effect’ and its operation in a range of contexts; ending with a reflection on the boomerang’s strategic lessons for the 21st century Western Left. Read more here.