The real definition of the word "Curfew"

Policing is itself a kind of endless curfew. To the defenders of order, there are always fires that need covering because there is always disorder lurking in the populace, threatening to burn the system down.

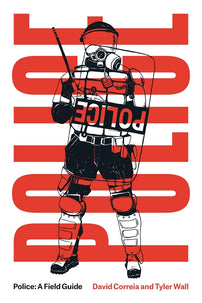

An excerpt from Police: A Field Guide by David Correia and Tyler Wall.

Download Police A Field Guide as a free ebook here (if you are able to, please donate the price of the book to a local bail fund, legal defense fund or community empowerment organization).

A curfew is a form of incarceration. It is the police regulation and control of the movements of members of a population through the restriction of time and space. The policing of curfew is always underwritten by force and violence. Like roundups, K-9 police dogs, and police helicopters, curfews impose limits on the time and space of, usually, the poor. Often referred to as a “lockdown,” a curfew is at once a police ordinance and a carceral formation. It transforms both public and private spaces into spaces of captivity, with the choice: disobey and be captured by police; obey and become a prisoner in your own home. A curfew seeks to purify a particular public space through threats of detention and arrest, while simultaneously transforming private living quarters into makeshift holding cells.

Curfews emerge out of a profound ruling class fear of working class revolt, not simply disorder. The word originally meant to “cover fire,” which comes from the medieval European practice of ringing church bells to designate the time at which residents were required to extinguish their outdoor fires and return to their homes. With cramped wooden living quarters, fires posed a grave threat to local towns and villages. But curfews were not merely about accidental fires. They were also aimed at the political fires of insurgency and revolution. Curfews have long “served the interests of the ruling class to avoid having groups of peasants and townspeople congregating in taverns, and later, coffee shops” where they might be plotting rebellions and revolutions.1 The etymology points to the animus of ruling-class power. Curfews are counterinsurgency. They are the normalization of emergency powers in liberal democracies, a key weapon for policing workers, the unwaged, rebels, and those yet able to work, like youth. Modern life is life under curfew.

In the United States, the curfew is among the first legal measures authorities turn to when policing crises, unrest, and general disorders of “crime” and “delinquency.” For instance, in 1703 the city of Boston created a curfew for Blacks and Native Americans, largely as a means of preventing revolt and insurgency.2 Alongside slave patrols and vagrancy ordinances, the curfew was an important tool authorities used to police slaves, and sometimes poor whites, in routine, everyday ways. The curfew was also the key way that white planters restricted opportunities for slaves to organize and socialize after dark, for fear of slave uprisings. Curfews were a common feature of the post-slavery Black Codes, and often worked in tandem with vagrancy laws to control the movement of recently freed slaves. Likewise, the “Sundown Towns” of Jim Crow America were white towns premised on the very notion of a curfew, but only for Black people. They excluded Blacks, espe- cially at night, and would post signs that read “Nigger, Don’t Let the Sun Set On Your Back.”3 The curfew was still in use a century later as a way to police riots and protests related to the civil rights and anti-war movements in the 1960s.

US counterinsurgency documents describe the curfew as one of many “populace control” measures conforming to the “rule of law.” Curfews played a role in the recent US wars against Iraq and Afghanistan, and were used in the war zones of World War II and Vietnam, as well as domestically, such as in facilitating the internment of Japanese Americans.

Curfew arrests made up the majority of arrests (42 percent) in the LA riots in 1992, and in the Cincinnati riots in 2001—both of which were in direct response to police violence against Black men. The curfew was used extensively in the “Battle of Seattle” in 1999 and against the Occupy Wall Street protests in 2011, as well in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Most recently, curfews were used to quell the Baltimore and Ferguson protests and riots in the aftermath of the police killings of Michael Brown in August 2014 and of Freddie Gray the following April.

But the curfew has long been used as a routine measure of structuring the everyday lives of the racialized poor, especially young people. Many US cities and communities have youth curfew ordinances for the summer months, or even year-round, which give police wide discretion to stop virtually anyone who looks under age and is in public after a specified time. Curfews that target youth also target the entire family. Parents are held responsible and can be deemed legally unfit if their children are caught out during a curfew. For example, when Baltimore enacted its emergency curfew to police the uprisings of 2015, critics pointed out that Baltimore already had on its books a year-round curfew for youth under fourteen, which penalized parents $50 for the first citation and subsequently fined them up to $300 or led to jail. Curfews are about more than just the policing of public space—they necessarily police morality and family, too.

The curfew is a mainstay of contemporary political power, but its effectiveness as crime control is by and large unsupported. Research since the mid–1990s has demonstrated that juvenile curfews, for instance, do very little to actually suppress crime and delin- quency. “What is certain,” according to sociologist Loïc Wacquant, “is that these curfews significantly increase chances of incarceration for the young residents of poor urban areas,” with police commonly arresting for curfew violations than other forms of violations.4

Whether in response to a crisis or targeting “delinquency,” the curfew always seeks to produce a specific kind of space by actively policing what types of people and behaviors are allowed to move in and across that space. This is what Don Mitchell means by the “annihilation of space by law,” which “is unavoidably (if still only potentially) the annihilation of people” because the curfew is not merely a prohibi- tion against unwanted behaviors, but a prohibition against specific types of unwanted people.5

For someone other than cops and legal authorities to be out legally during a curfew they must prove they are not only an adult, but also a worker. This is stated directly in most curfew laws: unless going to and from a place of legitimate employment, you are not granted legal permission to be out past a certain time. The age threshold for youth curfews is usually premised on the legal age requirement for employment. The curfew dances to the rhythms of capitalism.

The curfew is an anti-public policy. It demands that all of us, at all times, justify our public existence by proving our status as workers. It demands we all just stay home, isolated from a nighttime social life outside of the bourgeois family, preparing for the next day of work—and if you are to be out, you better be buying something or working for a wage. It is the ruling class’s hatred of any mode of being that doesn’t make them a buck. The curfew is the ruling class distrust for all the parts of our lives that aren’t yet subsumed by the laws of capitalist labor and the wages of work.

Policing is itself a kind of endless curfew. The logic of curfew animates the traffic stop and stop and frisk, and the police patrol as much as the slave patrol. The spirit of the curfew is present in the policing of suspicious persons who are supposedly out of place, and whenever the cop says “Hey, you there” or asks “Where are you going?” or “What are you doing here?” Wherever there are cops, the force of the curfew is mobilized, even when a curfew hasn’t been formally declared. To the defenders of order, there are always fires that need covering because there is always disorder lurking in the populace, threatening to burn the system down.