What Clarence Thomas Said

Judith Butler on Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, and the consequences that the decision, one that aims towards the restoration of patriarchal order backed by the force of federal law, will have for the wider movement for social justice.

The recent Supreme Court decision, Dobbs v. Jackson, strikes down Roe v. Wade (1973), the case that established the right to abortion as a federal right in the US. There is still no federal ban on abortion, but the right to have an abortion is now in the hand of individual states to decide. If a federal ban comes to pass, it would have to be passed by the US Congress and, as of right now, there does not seem to be a majority in either house willing to take that next step. At the time of the writing, it is expected that a dozen states will effectively outlaw abortion in the coming weeks, and those seeking abortions from those states will have to travel to other states (although travel for that purpose certainly will be outlawed by some of those states, thus raising the spectre of a new form of border surveillance). Wealthy people will doubtless find a way to secure the procedure, engaging private doctors under confidential arrangements, or by traveling to states where abortion remains legal. Especially for the poor, abortions will once again become back-alley operations, conducted in unsafe environments, with dire consequences for those who are forced to take that route. The withdrawal of a federally guaranteed right to abortion not only restricts the freedom of women but intensifies gender inequality, enhancing state control over their bodies. But does it potentially affect other groups, including social movements whose legal victories have depended upon a similar rationale and shared precedents?

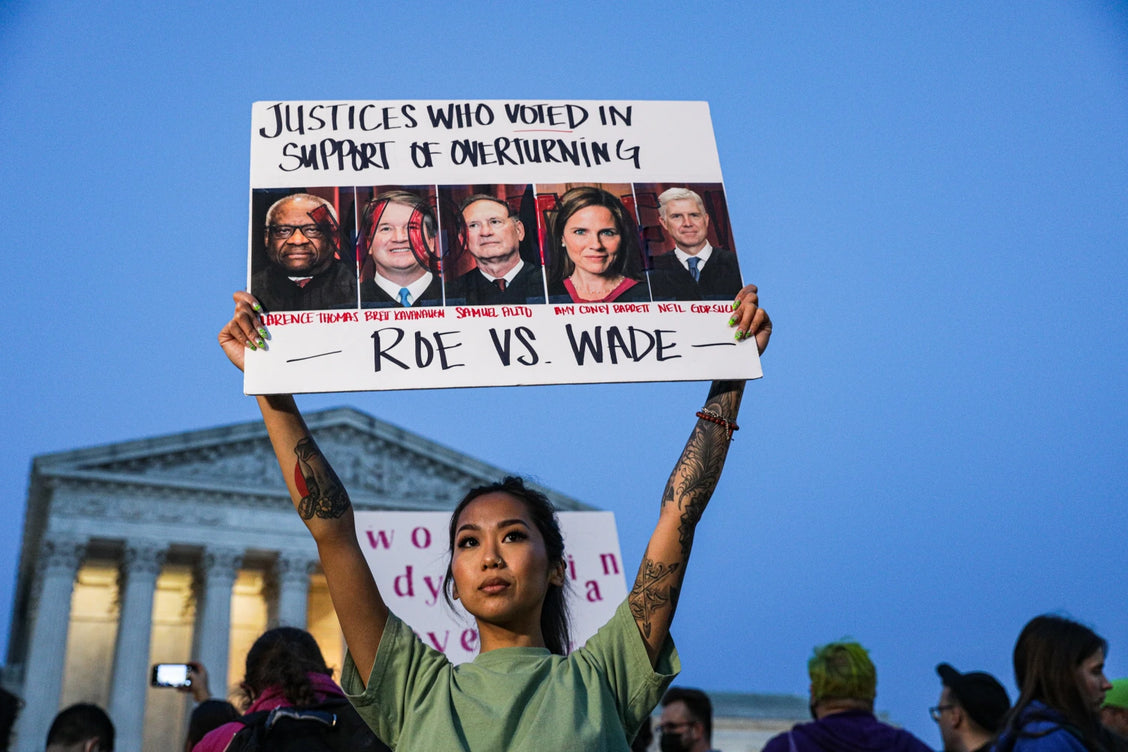

The court decision shows that the majority, although agreeing on the repeal, offer divergent perspectives on why they voted as they did. Those who voted against abortion rights clearly do not fully agree with one another on all issues, especially on the consequences of the ruling for other constitutional rights. One of the most controversial claims made in the ruling was issued by Judge Clarence Thomas, who forewarned that the overturning of Roe v. Wade would be but the first of such rulings, and that key Supreme Court decisions based on the privacy doctrine introduced by Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) would now be vulnerable to repeal: those rulings guaranteed gay marriage, rights of access to contraception and to provide medical advice about it, and the eradication of criminal punishment for those who engage in what the law called “sodomy.” The slogan now circulating throughout social media, and recently repeated by California Governor, Gavin Newsom, warns against Thomas’ plan: “They are coming for you next!”

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]Sam Alito, the judge who authored the recent ruling against Roe, insisted that this decision pertains only to abortion, but not to any other constitutionally guaranteed right. No other Supreme Court justices echoed Thomas’ call to “reconsider” these other rights, but perhaps they were staying quiet. They have a habit of doing so, until they decide to act. Indeed, prior to the overturning of Roe, many justices who voted to overturn Roe stated their support for Roe. Cavanaugh, in pre-appointment meetings with Senators, affirmed that Roe was established precedent, the “law of the land,” and that good judicial decision-making should not trouble those waters. Indeed, most conservative justices, including Gorsuch who joined the majority, argued against the past “activism” of the Supreme Court, understood as the unjustified overreach of left and liberal justices alone. Time and again judicial conservatives have said that judges should stick to the letter of the law, including the binding force of precedent. They broke with this line of reasoning by ruling against abortion rights that have been on the books for 50 years, marking the fact that they oppose the majority of the people in doing so, and have entered into the political fray. Boosted by the Trump-appointed Amy Coney Barrett whose religious commitments are front and center, the Court has delivered a ruling expands and intensifies “the state’s interest” in the fetus, overriding any rights that a pregnant person has to secure an abortion from choice or on the grounds of bodily integrity (including potential harm to one’s well-being). Clearly, the state’s power over women, their sexuality and their freedom, their right to health care has now become frankly frightening and grotesque. But that is not the only danger we now face.

In Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), previous Supreme Court made clear that it thought Roe v. Wade was decided on illegitimate grounds. Alito echoes that case when he insists that there is no right to abortion to be found in the constitution, and no legitimate way to derive that right from its existing language. In Dobbs, the Supreme Court did not overturn Griswold v. Connecticut, but Thomas ominously pointed to that precedent as a potential new target. He stated that the court “should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell.”

What does due process have to do with this ruling against abortion rights? Or, indeed, with the rulings that prohibited the criminalization of using birth control or giving advice about it (Griswold), that prohibited acts of sodomy (Lawrence), or upheld the rights of gay marriage (Obergefell). Substantive due process rights are established by the 5th and 14th amendments of the US constitution, and refer to freedoms that ought not to be infringed upon by any state authority. They are generally taken to be private or personal in nature, or ones that belong to the freedom of individuals. Although sodomy, abortion, and birth control are not mentioned in the Constitution, they have been held to be protected activities by courts who have applied due process principles to those cases precisely because they are personal and private and pertain to individual freedom. For Alito to claim that he cannot find the term “abortion” in the Constitution, or for Thomas to claim that none of these rights can be found there, is effectively to refuse the application of abstract rights to concrete social issues that the Constitution did not, and could not, foresee in their present historical forms. On the one hand, the conservatives have clearly become the activists. On the other hand, they pursue their agenda through a mind-boggling literalism.

One reason not to dismiss the threat delivered in Clarence Thomas’ concurring opinion as the lone voice of an outlier is that the Court has been sending mixed signals about its intentions for some time. Activists in the reproductive rights movements have known about this threat for some time, and Thomas simply now carries the torch that has been passed to him by conservative evangelicals. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), the Court affirmed the basic principle of Roe v. Wade that women had the right to exercise their own choice on the matter of abortion without state intervention, held that states may not prohibit abortions before then time when a fetus could survive outside the womb - about 23 weeks into a pregnancy.

In that same 1992 ruling, the Court nevertheless cast doubt on its legal status. There the Court stated plainly that it was not ready to make such an “unpopular decision” even though it maintained that the key finding of Roe that abortion is justified through recourse to the Due Process Clause is not justifiable. They did not recognize the “liberty” of women – Alito now adds those scare quotes - to terminate pregnancies as a freedom to be protected from state powers, and they affirmed the state’s legitimate interest in the fetal life, but at that point limited the reach of state interference. The Court refused to act upon its conclusions in that case thirty years ago, but their commentary surely predicted what conservatives now call the more “courageous” decision in Dobbs to repeal Roe.

If Thomas has his way, and if he speaks openly about a conservative agenda that others on the Court have yet to claim as their own, a number of social movements will see some of their most hard-won and indispensable rights nullified at the federal level. Rights of equality, freedom, and justice remain abstract rights until they are implemented in concrete historical circumstances, compelled to respond to, and adjudicate, new social realities over time. When we ask, does the right to be free include the right to marry someone of the same gender, we now say yes, and in so doing extend and expand our idea of freedom, making an abstract principle concrete and changing the concept for which that principle stands. Both freedom and equality take on new meanings. Or, in the case of the emancipation of slaves, the legal establishment came to realize that prior historical ideas of freedom were restricted to white property and slave-owners. Luckily, our ideas of freedom have changed through time, and it is incumbent upon courts to reconsider and reformulate freedom in response to legitimate historical challenges. In Obergefell, the Court states that fundamental rights do not emerge from “ancient sources alone” but must be viewed in light of evolving social norms. History invariably enters decision-making processes. Indeed, that crucial decision to establish gay marriage rights warned against basing law exclusively on traditional practices and arrangements with the consequence that nontraditional partnerships would be prohibited from claiming equal rights to heteronormative marriages. Here as elsewhere, conservatives have called into question whether new freedoms should really count as “liberty” if evidence for them cannot be found in the language of the law. And we are seeing the Court, that is, the most powerful judicial instrument of the US, assert state interests in reproductive decisions over any claim that women may have. We may not think this has much to do with state legislatures banning books that contain references to sexuality and gender, prosecuting parents who seek health care for their trans kids, or fresh attacks on LGBTQIA+ people, but think again.

There are at least three consequences of this analysis worth stating. The first is that we would be making a mistake if we thought that the Court is only interested in abolishing abortion as a federal right. The arguments against abortion can be used against any number of decisions that assume that new rights emerge from new social conditions pertaining to sexuality, gender, intimate association, and reproductive freedom. The point is not that they will go after abortion first, gay marriage second, and contraception third. No, the legal framework that is emerging targets the very idea of new historical formations of freedom (and equality) and seeks a restoration of patriarchal order backed by the force of federal law. Second, the vilification of women who seek abortions as abusers or murderers echoes the attack on sex education in states such as Florida, Texas, and Oklahoma, where teachers who teach topics such as gender or sexuality, are now accused of abuse or indoctrination, or parents who seek health care for their trans kids are to be reported to governmental authorities for child abuse. What about the refusal to recognize the legal rights for trans people and their right to health care, including abortion? In each of these cases, “the state’s interest” is enlarged through the eradication of fundamental freedoms, those that belong to women, to trans people, indeed, to LGBTQIA+ people, to educators and academics, to policy makers, and legislators working for greater social freedoms and equality. Lastly, the right wing has gathered many of us together as a single target, as we see from the tactics of the anti-gender ideology movement now operating on a global scale. Our task is not to scatter into our own identitarian corners clutching one agenda at the expense of others, but rather to gather ourselves into a more overwhelming and powerful movement. That means that feminists join with trans people, that gay marriage advocates join with those fighting for queer and trans bars and community spaces, that reproductive health is on every agenda for all kinds of women and men, non-binary people, including trans and genderqueer kids, as should be protections against gender and sexual harassment and violence. But none of this will work if we fail to see how those most badly affected by these new forms of disenfranchisement are poor people of color in the “unfree” states. And we cannot have a decent coalition without smart and radical lawyers who can contest and stop this legal trend. If the Right gathers us into a target more effectively than we gather ourselves into a movement, then we are lost. So, let us get smart about the powers of coalition and revise and refine our claims to freedom and equality as social, collective, historical and historic - and indispensable.

[book-strip index="2" style="display"]