Histoire du cinéma

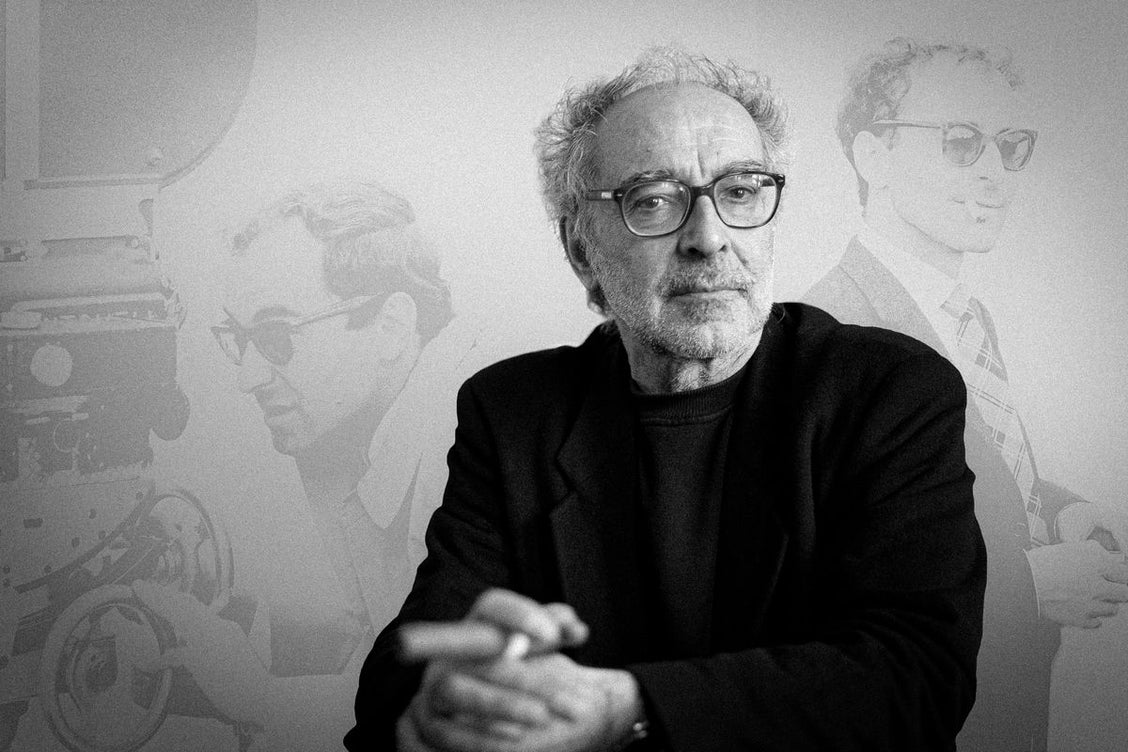

With the death of Jean-Luc Godard on the 13th September at the age of 91, cinema lost one of its most important and consistently radical practitioners. Here, Andrew Key looks at his formally innovative late work, including Histoire(s) du cinéma, his monumental eight-part 266-minute experimental video series made between 1988 and 1998.

The day after Jean-Luc Godard died I watched Histoire(s) du cinéma, his eight-part 266-minute experimental video series made between 1988 and 1998. I’d often thought about watching it in the past, but I never felt particularly motivated to spend four and a half hours with late Godard. It’d be quite some time since I’d last taken him seriously: I hadn’t watched any of his films for several years, and even then I would only be one or two, almost by chance, every few years. The last time I saw anything of his in a cinema was in 2014 when I saw his penultimate work, an experimental 3D essay film called Goodbye to Language, which left me cold, a little bored, a little irritated.

I hadn’t always felt this way about Godard. He was there at the beginning for me, as he was for so many other cinephiles. As a teenager I watched his groundbreaking films from the early 1960s, À bout de souffle, Vivre sa vie, and Bande à part. I had no frame of reference for what I was seeing, no understanding of these films’ skewed and antagonistic relationship to cinematic form and style, no concept of Godard’s studious attention to and reconfiguration of the grammar of filmmaking. I don’t think I even knew that there was such a thing as cinematic style. I had no inkling of Godard’s politics, his radicalism, and I wouldn’t have been able to make sense of it anyway, even if I had. I knew less than nothing about what I was watching. But these films set off something potent; they suggested a different way of living, a kind of life that was different to the provincial tedium of the English West Midlands that I’d been mired in so far. Early Godard offered an expansion, an alternative; I watched these films, shocked to learn that life might be thrilling, that people might be charismatic — louche, sophisticated, wry. Even coming to them in complete ignorance of the context of the Nouvelle vague, Godard’s early work was a revelation, and seeing these films changed my life.

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]After this initial infatuation, I stopped watching Godard’s films for a good while, feeling that — and it shames me now to write this — since I’d seen a couple of his films once or twice, I was done with him. I got the picture, I didn’t need to revisit his films, or explore any more of his lengthy and extraordinarily prolific career. There were so many other films to see, and the more of these I watched, the less interested I seemed to be in Godard. He opened me up to a new form of cinematic experience, and I learnt from him, and then I discarded him, imagining myself to be somehow above his work. For a long time I thought of Godard as the kind of filmmaker that one grows out of: an adolescent infatuation, useful at a particular age but slightly embarrassing to be interested in after a certain point. This is a kind of snobbery, a dismissive arrogance. And anyway, I was only really familiar with the first five years or so of a career that spanned eight decades, from the 1950s to 2022. I had occasionally watched some of the Dziga Vertov films –– the collectively made, revolutionary films Godard produced in the early 1970s –– but never with much enthusiasm, never quite bothering to distinguish them from the earlier films. I was in the habit of thinking of Godard with, at best, ambivalence. More often than not, I dismissed him out of hand.

I’m not proud of this attitude towards Godard now, and in the week or so since his death I have been reevaluating my own relationship to his work. I watched all eight parts of Historie(s) du cinéma straight through, letting the film wash over me. I won’t claim to have understood it, but I don’t think it’s a work which has the viewer’s comprehension as one of its aims. It is a monumental work of great erudition, one that employs multiple languages (I caught — though did not usually understand — snippets of French, English, German, Italian, Russian, Japanese, Polish, Swedish; there are surely more) and ceaseless textual, verbal and visual punning to plumb the depths of the cinematic void, breaking the idea of a film into its constituent elements — image (photography, film, montage, collage), sound (speech, music, noise, silence), text (quotation, narration, subtitle, intertitle), — all of which swirl around and confront each other in a process of conflict and reconciliation. It’s a film that relies heavily on repetition, circling back to the same concerns and anxieties without resolving anything, propelled by its obsessive fixation on the political history of cinematic form and style. It puts the viewer at sea: at points I felt relatively confident that I recognised most of the films Godard was quoting from, or that I had read a few of the books he cited, or that I grasped the connection between two clips he placed in dialogue. But these fleeting glimpses of comprehension felt like moments of calm in the middle of a tempest. For the most part, Histoire(s) is an overwhelming experience. Godard continued to make films after he completed Histoire(s), but on a reduced scale, not attempting anything so long or dense again.

Both magisterial and stupefying, Histoire(s) du cinéma is the culmination of a lifetime of obsessive film watching. It’s a film so dense that a number of writers compared it to Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. As the critic Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for the Chicago Reader in 1993:

For just as Finnegans Wake figuratively situates itself at some theoretical stage after the end of the English language as we know it — from a vantage point where, inside Joyce’s richly multilingual, pun-filled babble, one can look back at the 20th century and ask oneself, “What was the English language?” — Godard’s babbling video similarly projects itself into the future in order to ask, “What was cinema?”

Rosenbaum praises Historie(s), but when you read his response you might be forgiven for thinking he dislikes the film. Calling it ‘unwatchable’, meant in the same way that Finnegans Wake is ‘unreadable’, Rosenbaum reflects on the difficulty of grasping Godard’s work when the viewer has imperfect French and no knowledge of Russian (among the other languages present in this most polyglot film). The film is a modernist Babel; trying to understand it, I’m reminded of Ezra Pound’s fractious argument in ABC of Reading that anyone serious about poetry should know at least Greek, Latin, French, Italian and at least a smattering of Chinese. But, as is the case with Joyce, even if a viewer knew everything that Godard knew — had watched and read everything that he had read — even this wouldn’t be enough to fully comprehend the work, one that becomes more than just the accumulation of all of its details. It is through Godard’s aesthetic transformation of its materials that Historie(s) du cinéma becomes what it is, just as it is through Joyce’s handling of his omnivorous knowledge that Finnegans Wake exceeds the sum of its parts.

Think of the challenges which the subtitler faces when confronted with a work like Histoire(s), in which multiple voices speak at once, at the same time that text in various different languages appears on screen. Which voice do you translate? What do you prioritise? In his works from the 2000s in particular, Godard was interested in the role of the subtitle in cinema, the way that the international market required the imposition of another text on the bottom of the cinematic image. His 2010 work Film Socialisme, which already contains multiple languages, was screened with subtitles in what Godard called ‘Navajo English’: vastly compressed, with much of the dialogue untranslated and wide spaces between the few words that do appear. Typically, subtitles are supposed to be invisible, a technique which allows for the easy flow of commodities through international film festivals. By experimenting with their presence in his film, Godard worked to remind spectators that their role in the face of a film was to look, rather than to read.

[book-strip index="2" style="buy"]But of course, with Godard it’s never quite as simple as the mere opposition between image and text, with the image prioritised over the words. Indeed, from the very beginning his work was deeply concerned with literary history, which, along with the histories of the cinema, of music, and of the plastic arts, takes up a crucial place in Godard’s aesthetics. A dialectic unfolds between quotation and citation in Histoire(s): elements, extracts and snippets from certain films or literary works or musical compositions appear in the film itself. And these are encircled by a number of other intertexts which appear only by name — their titles appearing on screen in imposed text, or spoken aloud by Godard as he stands by his bookshelves, picking up various books and reciting their names. As in his other work from this period, such as 1991’s Allemagne 90 neuf zéro, Godard ensconced himself in the history of European culture — his engagements with literary history at points feel as significant as his relationship to film history, and his erudition is imposing.

Throughout his career, Godard’s films engaged with the written word, but in the later films particularly — from the late 1980s onwards — literature becomes a barricade against the disappointments of the course of the twentieth century. Allemagne 90 neuf zéro is a melancholic reflection on the state of Germany in a time where alternatives to capitalism appeared to have exhausted themselves. It expresses a deep knowledge and love of the history of German literature — albeit a love tempered by profound ambivalence. This work is unashamedly intellectual, rigorous in its thinking, deeply serious. There is still an occasional playfulness here, but it’s a far cry from the vigour of the nouvelle vague period; thirty years later, Godard’s films are imbued with loss and mourning, and his erudition feels like an edifice erected against the ruins of the twentieth century.

In Godard, actors are often filmed reading aloud — in Allemagne 90 neuf zéro, for example, we see a man reading Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit in German while a woman reads the same text, at the same time, in French; later, another character reads Thomas Mann’s Lotte in Weimar. Books also play a role in the work of Éric Rohmer, Godard’s colleague former at the Cahiers du cinéma. But whereas in Rohmer’s work a book is always more or less just a prop, for Godard the book’s content is the important thing.

His relationship to literary history is also different from that of his contemporaries. Godard also differs from other challenging modernist filmmakers such as Jean-Marie Straub, whose films — made with his wife Danièle Huillet until her death — often take the form of extremely unconventional literary adaptations. Straub–Huillet enter into their source text fully, using it to ‘start the fire’ of their own work: the difficulty of watching their films comes in part from their willingness to show the literary text’s resistance to the process of being adapted. The text insists on its independence in opposition to the film, in a confrontation which makes legible the tensions in the work of the directors. Godard did not make adaptations in the way that Straub–Huillet did, but he was as committed to the radical currents of literary history as Straub–Huillet were. In Godard, the contents of the book become woven into the material of the film, integral to its movements. For Straub-Huillet, a literary text becomes the chessboard, the ground on which the film unfolds; for Godard, literary texts are the chess pieces.

With his death, we have lost a modernist artist of incomparable stature. Godard’s unstinting commitment to political and aesthetic radicalism meant that he trod an increasingly lonely and unpopular path. Like other major experimental artists, his work was typically misunderstood and dismissed; he was often reduced to a caricature based on only a few, better-known works. I hold my hands up to making this kind of dismissive reduction, and am trying to atone for it. Godard was an undeniably major figure, whose career demonstrates that it is still possible for artists to carve their own paths, to refuse to compromise their work for the sake for the market. He was one of the last links to a period of radicalism from which we can still learn profound lessons — not least a lesson about life-long commitment.

Andrew Key is a writer and film critic. He is the author of a novel, Ross Hall (Grand Iota, 2022) and his essays have appeared in numerous publications. He writes a weekly Substack called Roland Barfs Film Diary.