Feminism and the Politics of Pleasure: Lynne Segal on Straight Sex, Second Time Around

This text formed Lynne Segal's lecture from 'Radical Thinkers: the art, sex and politics of feminism' at the Tate Modern, 9th February 2015. The event with Lynne Segal, Griselda Pollock and chair Sonia Boyce, addressed the legacy of feminist art and theory and its enduring relevance to contemporary struggles. Visit the Tate website to watch the video of the event.

Agonism, challenge, contention! Start talking about sex today, and soon enough, trouble looms – unless we stick to jokes, or gender cliché. Agreement is usually hard to find, and not just for feminists! Although feminists certainly face very special problems, trying to tie the protean complexity and intangible nature of intimacy and desire to any sort of feminist sexual politics. This was never just a Mother-Daughter affair – though it was often enough presented as that. We challenged and fought with each other, from the beginning – as straight, lesbian, Black and working-class women, and more.

It wasn’t, in fact feminists, but William Reich, who first talked about ‘sexual politics’, back in the 1930s, criticizing the repressiveness of bourgeois sexual morality, which doubled as sexual hypocrisy, while he watched the rise of fascism in Europe. Reich’s Sex-pol aimed to free sexuality from the constraints of religious moralism and compulsive patriarchal monogamy, while seeing this as only achievable after the end of capitalist exploitation, with the coming of socialism. Times change, and then again, as we know only too well, its traumas return.

For certain, massive sexual hypocrisy and double standards helped inaugurate Women’s Liberation, at the close of the 1960s. At long last, talk of ‘sexual liberation’, not punitive moralism, was bubbling up, especially around young women, suddenly free, apparently, to flaunt our sexuality as never before – though preferably in a rather peculiarly child-like, frivolous way, it seemed.

I arrived in London in 1970, when the optimistic, hedonistic, oh-so-resolutely youth-oriented culture of Swinging London was still evident everywhere. That teenager Twiggy, insect-thin, looking just like a child in adult drag – displayed mouth open, sucking her thumb, or riding her baby scooter, had been the leading London fashion icon for the previous 4-yrs. Though she was now retiring, having reached the grand old age of 20.

Thus, if to be young then was, 'very heaven’, it had many pitfalls. Youth being so very fleeting, and women, above all, needing, forever, to ‘keep young and beautiful’, if we were to be loved, as Eddie Cantor once crooned.

For sure, many of us young women then were eager to partake of the new sexual freedoms that came along with the consumer-oriented swinging Sixties, a time of full employment, increased wages and, by the close of the decade, for some of us, youthful rebellion. We took to the streets, and were more active between the sheets (liberated, or partly so, by the marketing of the oral contraceptive, simply ‘the Pill’, as it was known). Having sex, and flaunting rather than hiding it, was the single main way some young women in the Sixties felt we were rebelling against parental and bourgeois norms. Thus fashion entrepreneur Mary Quant proclaimed in 1969: ‘Now that there is the pill, women are the sex in charge. … She's standing there defiantly with her legs apart saying "I'm very sexy, I feel provocative, but you're going to have a job to get me … you've got to be jolly marvellous to attract me.”’

Well, I think Quant was wrong about most women’s sexual confidence back then, whatever our youth, shiny Biba mini-skirts, or parted legs. For, despite all the flaunting of young women’s sexuality, the Sixties remained, overall, a quintessentially male decade. Once out of our teens, it was the association of women with ‘Mother’, and with domesticity, which the radical world I entered as a young woman abhorred. The so-called ‘Angry Young Men’ the ‘60s celebrated were all tough, amoral, anarchic male heroes – like those in Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night & Sunday Morning, or crazy outsiders, as in the film Morgan, or ethereal love objects, like Dylan’s ‘sad-eyed ladies’, waiting for their ‘Bobby’ to return. Street-fighting Man, working class heroes, were battling women, and any constraints of domestic responsibility, along with other authorities.

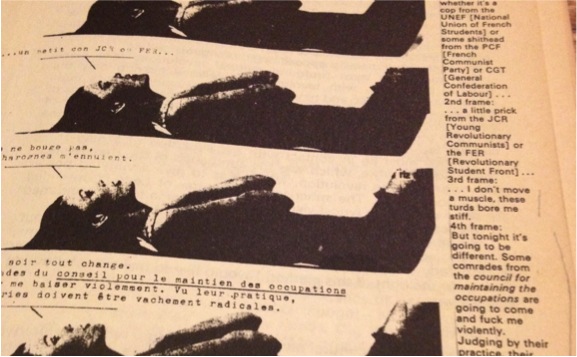

Moreover, those of us who were part of the radical Left– in students movements, civil rights or anti-Vietnam war protests – confronted the more explicit sexism of the underground press, with its pin-ups and psychedelic porn – present, as well, in much May ’68 graffitti.

Predators and Prey: May 1968 Some comrades from…the occupations are going to come & fuck me violently. Judging by their practice, their theories must be truly radical

Thus it was unease around our place as sexual beings that was one of the key triggers for the emergence of the women’s liberation movement. 45 years ago, the young Sheila Rowbotham (at the time the only woman on the radical magazine Black Dwarf), beautifully summed up how many radical women felt about the men in lives at that moment: 'Men … you have nothing to lose but [your] chains … You will no longer have anyone to creep away and peep at with their knickers down, no one to flaunt as the emblem of your virility, status, self-importance, no one who will trap you overwhelm you, no etherialised cloudy being floating unattainably in a plastic blue sky, no great mopping up handkerchief comforters to crawl into from your competitive, ego strutting alienation ... [but women] who will understand you when you say we must make a new world in which we do not meet each other as exploiters and used objects ...’.

At least that was the mood among most of the women's liberation groups that began meeting in Britain in 1969. Women wanted to talk about sexuality, but in all the ways missing from men's talk: the embarrassment and anxiety still surrounding our bodies, issues of fertility and our right to choose when and if to have children; our dislike of the pin-ups saturating the alternative press; men's fear of women's independence, especially our sexual autonomy; problems surrounding housework and childcare; fear of men’s potential violence and coerciveness. This was the mood that produced the first commercially successful British feminist magazine, Spare Rib, in 1972. 'It was [both] a product of the counter-culture and a reaction against it', as Marsha Rowe, who helped set it up, later wrote. This is why I concluded the first chapter of Straight Sex suggesting: ‘Saying YES to sex was seen as part of our liberation. But it had to be a feminist or 'liberated' type of sexuality, with, or without, a man. Thus women of my generation moved on from seeing sex as liberation, to seeking liberated sex’.

Liberated sex: there’s the difficulty. How on earth do we talk about that? It seemed to grow harder, not easier, as the years passed. Women’s Liberation began confidently enough: ‘Think Clitoris’, was how the well-known and ebullient American feminist writer Alix Kates Shulman summed up much feminist thinking on sexuality in 1971, as again I recalled in my chapter on the 'liberated orgasm'. In her popular novel Burning Questions (1978), Shulman had one young feminist mention “the 3 non-negotiable conditions [for good sex]: plenty of dope, three hours minimum and cunnilingus”.

Moreover, despite the fearful impediments she herself has faced, Shulman has remained largely optimistic and positive about her loving relations with men ever since. This, even though she would later write of attending a feminist meeting at the close of the 1970s when: 'All agreed that sex had changed for them’, often for the better, but this did not prevent them from being “unhappy in love”’. It would lead at least some feminists to turn to psychoanalysis as they began to explore sexuality itself as a crucible of contradictions and misunderstandings, especially between women and men.

Soon enough, however, that first flush of feminist confidence in building a world closer to our hearts’ desire – whether in the office, kitchen, or bedroom – was being beaten back by rising awareness of the prevalence of men’s violence against and their frequent sexual coercion of women. It was also weakened when we observed the abiding resilient of the phallocentric or male-centred nature of almost all our existing images and iconography of sex, desire and subjectivity – however much we earnestly tried to rethink and refashion them all. And then again, any simple feminist search for independence, parity and control in our intimate relationships met with the inescapable contrariness of sexual passion. Like it or not, and many of us did not, some level of confusion and contention were quite inevitable if straight women were to wade our way through that sea sexual contradictions.

Juliet Mitchell (whose Women's Estate has been reissued in Verso’s Radical Thinkers series) expressed some of this when Spare Rib interviewed her in the early 1980s. She was describing what emerged in the study group she was in addressing sexuality and sexual difference: ‘A sort of panic starts in the mind,’ she said, ‘We’ve found we just don’t know what sexuality is’ any more. This was certainly a problem, when the world at large tends to think it knows all too much about what sex is, who should practice it, and how. The difficulty was all the greater given the ever-expanding sexual marketplace, alongside media fashions and fixations targeting sexual fears and longing.

It certainly did not get easier as the conflicts within feminism continued to expand during what was called the sex wars of the 1980s, as leading feminist figures fought over the very meaning of ‘feminism’, wanting to place heterosexuality at the very core of women’s problems. Thus Catharine MacKinnon, like her fellow American anti-pornography campaigner, Andrea Dworkin, insisted that there was no way even to imagine any passionate harmony between women and men in the current terms of intimacy: 'What looks like love and romance in the liberal view,' MacKinnon insisted, 'looks a lot like hatred and torture in the feminist view.' Given the still prevailing iconography of straight sex, some found their views persuasive. Meanwhile, although proposed by a small minority of so-called ‘revolutionary feminists’, rows over the primacy to be given to men’s violence against women as the overriding cause of women subordination dealt the death knell to any future annual gatherings of Women’s Liberation, in Leeds in 1977: ‘Giving up fucking for a woman is about taking your politics seriously’, they argued.

It is certainly true that a bleaker climate was beginning to undermine all forms of radical politics from the 1980s, under Margaret Thatcher. These were also the years when HIV/AIDS began to return fear and danger to areas of sexuality, especially for gay men, as well aswhen the serial sex murderer, Peter Sutcliffe, was roaming the streets in and around Leeds. As the feminist ‘sex wars’ raged during the 1980s, it became dangerous even to discuss the ways in which sexuality itself, both women’s and men’s, were often steeped in fantasies involving the eroticization of power and submission. Feminist research focussed, importantly, on issues of safety, especially for young women, or on outlining the remaining, still ubiquitous cultural scaffolding of rape.

Meanwhile, as talk of desire and pleasure seemed to disappear from straight feminist writing by the close of the 1980s, a sudden renewed surge of confidence in defiant sexual dissidence was emerging in gay and lesbian writing with the birth of ‘queer’ in the 1990s. The vigour and joys of queer theory, which raced onto academic platforms throughout the 1990s, aligned itself, at least for a while, with the noisy protests of Act-UP & other activist campaigns, demanding government action around HIV/AIDS. This time citing the words of Judith Butler, Eve Sedgwick, Leo Bersani & others, queer scholars and activists could draw upon the life-long legacies of Freud’s polymorphously bisexual infant (while rejecting the normative deployments of p-a). This was combined with Michel Foucault’s questioning of there being any stable or unitary notion of sexuality at all – whatever our gender or sexual orientation. ‘Pleasure has no passport, no identity card’, Foucault said, hoping to detach the body & its pleasures from our understandings of gender & anatomical difference.

It was drawing upon both psychoanalysis and critical theory that I dared, in Straight Sex, to return again to all those questions we had raised in the first passionate days of women’s liberation. How might it still be possible to develop loving, pleasurable and responsible sexual politics around heterosexuality, I asked, given all that we now know about the easily shaken yet solid phallocentrism of the symbolic order; the androcentrism of discourse; the problematic ways of men – determined to shore up their entitlements to the insecure mantle of masculinity. We know that all three are up with our notions of masculinity and femininity via the existing conception of heterosexuality. It is thus ‘heterosexuality’ itself that must be challenged if we are ever to turn around the oppressive cultural hierarchies of gender and sexuality.

The first way to do this, I argued, was by questioning, not affirming, all the traditional assumptions around gender, in particular, rejecting that absurd active/passive divide, constructing what Butler called the ‘heterosexual matrix’. However secure or fragile our hold on power in most areas of our lives, it is desire itself that can render any one of us helpless – whatever our gender or sexual orientation. It is not so hard to notice that what actually happens in consensual sexual encounters often bears little relationship to those binary divisions that so oppressively insert themselves into our thought and langauge. In passionate sexual relationships, in love, we are all vulnerable. As Judith Butler says in Undoing Gender, addressing the perils of desire: ‘Let's face it. We're undone by each other. And if we're not, we're missing something. If this seems so clearly in the case with grief, it is only because it was already the case with desire’. In an earlier brief meditation on the risks of love she suggests: ‘love is not a state, a feeling, a disposition, but an exchange, uneven, fraught with history, with ghosts, with longings that are more or less legible to those who try to see one another with their own faulty vision’.

We certainly all need to face up to the strange unruliness of desire. For instance, it is surely not only sex workers who know that what men want, as often as not, is to be sexually passive. Of course, what men do most strongly do not want is for women – and even more, for other men – to know this. These are the thoughts that emerge most strongly in Straight Sex.

Knowing this, however, is one thing. Confronting violence in the world, a significant part of which is men’s abuse and sexual coercion of women, is another thing. I don’t, ever, want to ignore that violence. Just as, like one of my favourite feminists, Joan Nestle, I don’t either ever want to forget the shifting, diverse and playful erotics of power. It is possible to explore the contradictions of power and passivity in erotic couplings, in ways that need never interfere with our determination to oppose the systemic violence in human institutions and relationships. The latter is such hard work, and sometimes we need some escape from it. If we don’t have some idea of the difference between the psychic life of desire and routine endemic social violence, we really do not know anything much about either sexuality, or violence.