Paul Buhle picks his top 5 comics!

Comic art has been in my life since at least age 5, when I can recall my (older) sisters reading them aloud, a decisive part of my learning to read. If nonfiction comics happened to be my destiny, then Classics Illustrated, especially the William Tell comic with its heroic attack on the authorities, must have been predictive. Jump down to 1959 and Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book, a classic satirical assault upon modern American business culture-- wholly written and drawn by Harvey Kurtzman, the very first comic to appear as a paperback original—was my first of five. Too bad, for the massively influential creator of Mad Comics, that it was a commercial failure.

So-called Underground Comix transformed the art, but as a kind of continuing collective work, rarely abandoned the anthological form. Justin Green’s Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary (1972), oversized and unique in every other way, is said to have invented the autobiographical format through the artist’s hilariously tortured childhood story of religious confusion, somewhat fictionalized. The rich literary tradition of agonized memoir had no previous role in comics but with Green’s influence, was to blossom in the next thirty years. Green, very much part of the Underground scene centered in San Francisco and represented as an artistic force in many of the publications, hit the then-huge readership with a zany lucidity.

Because the Undergrounds crashed by 1980 and artistic outlets dried up, major artists and key anthological projects (including Wimmin’s Comix, originally It Ain’t Me Babe) struggled along and then, mostly, disappeared. “Alternative” comics of various types, erotic to historical (Jack Jaxon’s sagas of Old Texas the best representative of a new kind of nonfiction comic), and numerous reprints of 1900-1950 classics, included a small handful of precursive graphic novels like Milt Gross’s He Done Her Wrong (1930), arguably the very earliest of such in English. Art Spiegelman, whose future Maus began appearing during the 1970s, was, with Bill Griffith (of Zippy) co-editor of the doomed anthology Arcade, clearly on his way….to the avant-garde RAW magazine. There, as a short-time assistant, the artist with the next of the five Biggies for me took the field.

Cheap Novelties: the Pleasure of Urban Decay (1991) by Ben Katchor, does not fit either within or outside any easy definition of graphic novels. Katchor’s semi-legendary cityscapes, his wonderfully oddball characters and above all the sense of a vanished lower-middle-class Yiddishkayt once common in Manhattan and Brooklyn, added up to a world vanished but leaving traces behind. It was imagined history, imagined social history with the details overwhelming the story, and like Binky Brown, accomplished something never seen before in comic art, a narrative realized in art with the artist’s originality stamped on every page.

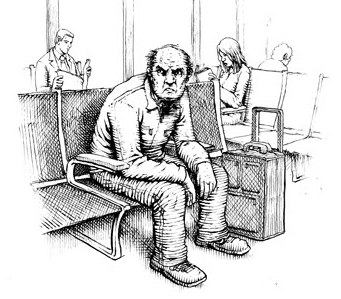

How a comic script-writer who is not an artist could accomplish the same degree of creative originality must be a mystery but one solved by Harvey Pekar. Actress Helen Mirren was to say, the year after Pekar’s death, that his collaborative work with artists had shown readers and artists how to read comic art in a new way. Harvey’s Cleveland, a blue collar town deserted by industry, is seen from the perspective of decaying neighborhoods but also from Harvey’s real-life job at a Veterans Administration hospital (where he worked, mostly as a file-clerk, for long decades). It was stunning and remains stunning, realized in book form first in the anthologies that began with American Splendor (1986).

No one after my first Harvey (Kurtzman, that is) could have influenced my own work as much as my second Harvey (Pekar) because with Pekar’s collaboration and encouragement, the series of comics that began with Wobblies! (2005) and has continued through a dozen more, under my editorial guidance, takes shape.

Selecting the last of five favorites offers me an impossible choice, and tilts me toward the unacceptable conclusion of “my” comics as personal influence because—through creative cooperation of editor or editors and artists--these have shaped my understanding continually, within the last decade. How would I not be? In Yiddishkeit, for instance, comics by Nick Thorkelson, Peter Kuper, Sharon Rudahl and others, likewise in Bohemians assorted comics by some of the same crew but also by Afua Richardson, Lance Tooks and Milton Knight: together, these have showed me what level of comic artistic achievement is possible, suited precisely to the subjects at hand.

For these reasons and leaving out so much—I count the memorable Fun Home by Alison Bechdel and any of the volumes of Lynda Barry—I arrive at the work of an artist who has never been inveigled to work with me. His singular work was the nearly unanimous choice of favorite textbooks by the students in my college course, “The Sixties Without Apology.” That is, Howard Cruse, whose award-winning Stuck Rubber Baby (2000)–my final choice--is the novelistic covering of a real life story, gay life in the deep South of the early 1960s.

marxism in

marxism in Given another five choices….no, I refuse to go there. The possibilities are too overwhelming, especially if we were to go backward and forward in genre and generation. I have not even mentioned Robert Crumb’s The Book of Genesis (2009), a volume that brings back the grand medieval art of illuminated texts. Nor have I referenced, from the next generation of artists, Noah van Sciver’s comic art path through the beaten-down youth of the twenty-first century. There is so much more to admire, and so much more in the course of appearing. Let me stop here and ask the indulgent reader to accept this offering.

Paul Buhle’s Radical America Komiks (1969), largely the artistic work of Gilbert Shelton, was the third “Underground” comic published, after ZAP #1 and (it came later) ZAP #0. He is also co-author, with Denis Kitchen, of the biography of Harvey Kurtzman.