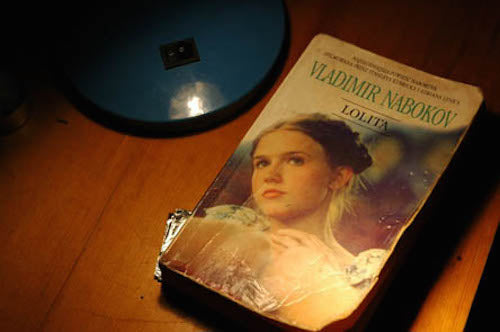

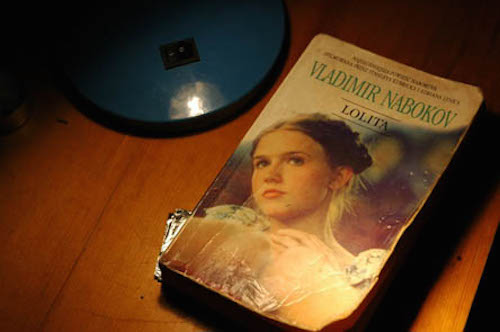

Who Wrote Lolita First? An Interview with Michael Maar

Michael Maar, the iconoclastic literary critic, caused a stir in the literary world when in 2005 he published his investigation into Nabokov's Lolita. Maar's book, The Two Lolitas, showed that Nabokov's work had a startling similarity to another Lolita, written some 40 years beforehand, by Heinz von Eschwege - a writer who would later became a famous Nazi journalist. A classic of literary sleuthing, The Two Lolitas asks whether Nabokov knew of von Lichberg's tale and if so, did he adopt it consciously, or was this a classic case of "cryptoamnesia," with the earlier tale existing for Nabokov as a hidden, unacknowledged memory?

In this interview, by German magazine Cicero and translated by the Paris Review, Maar discusses his investigation into the case of the two Lolitas.

In your book The Two Lolitas, you made an intriguing discovery—it started to obsess me a bit. What’s equally interesting, and kind of outrageous, is that most Nabokov scholars ignored your finding. Maybe they felt they ought to shield Nabokov from charges of plagiarism. So let’s get this out of the way first—is this about plagiarism?

Of course not. The word came up in the press when I published my first article about the discovery, but that’s not what this is about at all.

Let me sum it up. Heinz von Lichberg, a writer who’s completely forgotten today, and rightly so, published a volume of bad short stories in 1916, The Cursed Gioconda. In it there’s a story called “Atomit” in which a man develops a doomsday machine that can destroy the world. Nabokov wrote a play in 1938, The Waltz Invention—it’s about a man who develops a doomsday machine with the potential to destroy the world.

There’s more.

Lichberg’s “Atomit” begins with a scene in which the inventor meets with the U.S. Secretary of Defense to pitch his project. Nabokov’s The Waltz Invention opens in the office of the Minister of Defense of a powerful, unnamed state, where the inventor proceeds to pitch his doomsday machine. Coincidence?

Possibly. But there’s still more.

Nabokov’s inventor goes by the name of Waltz. He has a cousin whose name is Waltz, too. In another story from Lichberg’s collection, we also find two men who are close relatives—in this case, brothers—and their family name is Walzer, the German word for waltz. The narrator of this story falls in love with a young girl, the daughter of his landlord. A narrator who falls in love with his landlady’s daughter—that’s something we know very well from Nabokov’s Lolita. And what’s the girl’s name in Lichberg’s story? Lolita. And what’s the name of the story? It’s “Lolita.” Written by Heinz von Lichberg and published in 1916—exactly a hundred years ago.

The name alone wouldn’t prove anything, but if you look at all those other parallels—doomsday machine, inventors, Ministers of Defense, two relatives called Waltz—it’s safe to assume that Nabokov knew Lichberg’s book.

It seems to me a rational assumption, but Nabokov scholars are in near-complete denial. One of the few scholars who bothered to react was Dieter E. Zimmer, the editor of Nabokov’s Collected Works in German. He claimed that it’s all pure coincidence—but he only mentions a young girl named Lolita. He doesn’t mention the Waltz parallels. And Nabokov’s biographer Brian Boyd, what did he have to say? Well, not a lot. Quite a while after you made your discovery, he published a book of essays about new developments in Nabokov studies, which neglects to mention Lichberg at all. And recently he explained, in a Nabokov forum online, that there’s nothing unusual about two girls coincidentally having the name Lolita in the works of two different writers. Again, no mention of the doomsday machine, the Minister of Defense, the Waltz name. With all due respect, as a great admirer of Nabokov, I feel cheated.

We have to assume that these scholars are strictly neutral, with no personal interest at stake. But through some of the more heated reactions it became clear that there was one fact about Lichberg that people found hard to stomach—he was an ardent Nazi. He enthusiastically praised Hitler on German radio, his voice trembling with emotion. This was when Hitler became chancellor—you can listen to him on YouTube, if you really want to. Later Lichberg wrote articles for the Nazi paper Völkischer Beobachter. It may be hard to accept that Nabokov, who fled from the Nazis with his Jewish wife and whose brother, Sergey, died in the Neuengamme concentration camp, was linked to that kind of a man.

Nabokov incessantly teases his readers to decode his references—which is why it’s clear to me that this isn’t about plagiarism. It’s about a clear reference, about what Nabokov is trying to signal to us by alluding to the work of an unimportant German writer—a writer we have every reason to assume he would have loathed for literary and personal reasons—at the center of several of his works. And if this isn’t a signal for his readers, who does he want to signal to? That’s the question I find hard to ignore, and I find it exasperating that Nabokov scholars keep ignoring it.

There has to be a missing link. It’s not improbable, for example, that they knew each other in person. They lived in the same Berlin neighborhood for about fifteen years. Could Lichberg have been Nabokov’s landlord? Could they have been in the same tennis club? They were both good tennis players. I tried to look into that, but the membership lists of the Dahlem tennis clubs were destroyed in the war. Even if they had been in the same club, that wouldn’t answer your question—What was he trying to signal, and to whom? It doesn’t stop with the book, either. In his Lolita screenplay, which Kubrick didn’t use, he has someone ask whether the girl is Spanish. And when Humbert Humbert exclaims, in the same screenplay, that Lolita is not supposed to be “dancing a Waltz,” or when he gives her “the smile of a Gioconda.”

Lichberg’s story is set in Spain, and the title of his book is The Cursed Gioconda.

Exactly. It does seem like a wink.

But to whom? Lichberg died in 1951, and anyway, it’s very hard to imagine the two of them as friends. Also, some Nabokov scholars have been quite steadfast in their claim that the great man didn’t speak German, and if that’s true, he couldn’t have read Lichberg. But you just need to ask around a bit and you find out that’s not true.

Who did you ask?

Gerhard Bronner, a famous Austrian comedian and nightclub owner who died in 2007, told me how, years ago, the Austrian writer Friedrich Torberg brought Nabokov and his cousin Nicolai to Gerhard’s bar in the center of Vienna. Gerhard remembered Vladimir speaking very decent German, albeit with a heavy accent. But I really don’t think we even need this kind of anecdotal evidence. In my opinion, the parallels between Nabokov’s and Lichberg’s works would be enough in themselves to conclude that he must have known those stories—and that it’s likely he had some knowledge of German.

And let’s not forget that by his own admission he read Thomas Mann and Freud in the original—hating them fiercely, of course. And he did translate Heinrich Heine and Goethe into Russian. If you can do that, reading Lichberg shouldn’t be too hard.

The thing I just can’t get over here is that Nabokov keeps asking his readers to decode his references. But the Lichberg reference is something he couldn’t have assumed would ever get discovered, let alone decoded.

It’s certainly puzzling. He liked private jokes, though.

But of course he’s famously unforgiving when it comes to his judgment of literary or moral quality—and Lichberg was a bad writer and a Nazi! So why in the world would Nabokov reference him like this? What could have been his intention?

Anybody who offers me a good theory can have my first edition of The Cursed Cioconda. Which is a rare book! My personal guess would be that a good private eye could find out. Sorry, I’m just a modest literary critic.

Translated from the German by Daniel Kehlmann.

Postscript by Michael Maar

Only a few weeks after this talk—and one day before The Paris Review published it—I was reading Nabokov’s Letters to Véra and discovered what seems to be the missing link, if not the smoking gun. The copiously annotated letters show that Nabokov and Véra were lodgers at a certain Frau von Bardeleben, in Luitpoldstraße, where they remained from 1929 to 1932—a relatively long period of time, given Nabokov’s lodging habits. Vladimir used to call his landlady “Mrs. Walrus.” She was married to Albrecht von Bardeleben. The Nabokovs seemed to be quite familiar with the von Bardelebens. Even years later, in April 1937, Vladimir responds in a letter to Véra about some funny chat she must have reported: “How amusing—about Bardelebeness.” Evidently they stayed in touch with their ex-landlords somehow. Otherwise, why would they exchange news about these people five years after they’d moved out?

There’s one genealogical detail the rich annotations in Letters to Véra do not reveal. Remember that Heinz von Lichberg, who wrote the first Lolita, was the pen name of Heinz von Eschwege. Well, it turns out the Nabokovs’ landlords, the von Bardelebens, are related to the von Eschweges—Charlotte von Bardeleben, born in 1766, was married in 1787 to Johann Friedrich Ludwig von Eschwege. In other words: for at least three years Nabokov lived under one roof with the family of his infamous predecessor.

It doesn’t take much to imagine the rest. The von Bardelebens and the von Eschweges both belonged to the Hessian high nobility, and nobility weaves a meticulous web: everyone seems to knows one another and occasionally to meet. Heinz von Eschwege might have been a regular or sporadic guest at the von Bardenlebens; Mrs. Walrus might have clued in Nabokov to von Eschwege’s books. Or maybe it was the other way around, and Nabokov became a lodger at the von Bardelebens because he was already an acquaintance of Heinz von Eschwege. Research, as they say, is ongoing.